I don’t know about you, but I’m a huge fan of the creature design in Monster Hunter. The monsters are beautiful, believable, and have a ton of personality. A common pitfall I’ve noticed in creature design in general is that people tend to create “chimeras” of existing creatures–a lizard with the head of a lion and the tail of a scorpion or whatever–but Monster Hunter frequently produces creatures that have no real-world analog, but are still very plausible, which to me is impressive.

If you aren’t familiar with the series, I recommend you check out the newest installment, Monster Hunter Rise, first. The earlier titles had a learning curve that was sort of ridiculously steep, less variety of monsters, behaviors, weapons, and environments, and some of them suffered from terrible camera mechanics that required players to do this:

The infamous “Monster Hunter Claw”.

Anyway, the newest title keeps all the good stuff from the older ones and makes improvements on the bad. Playing Monster Hunter is surprisingly very Zen–you get into a rhythm of hit, dodge, heal, hit, dodge, heal, for up to 50 minutes. The monsters don’t have visible health bars, so you have to get familiar with their body language, vocalizations, and habits in order to effectively hunt them. And there’s no “leveling up” really–in order to do more damage, you have to make a new weapon out of materials obtained from a monster that’s currently difficult but possible to kill. Would recommend.

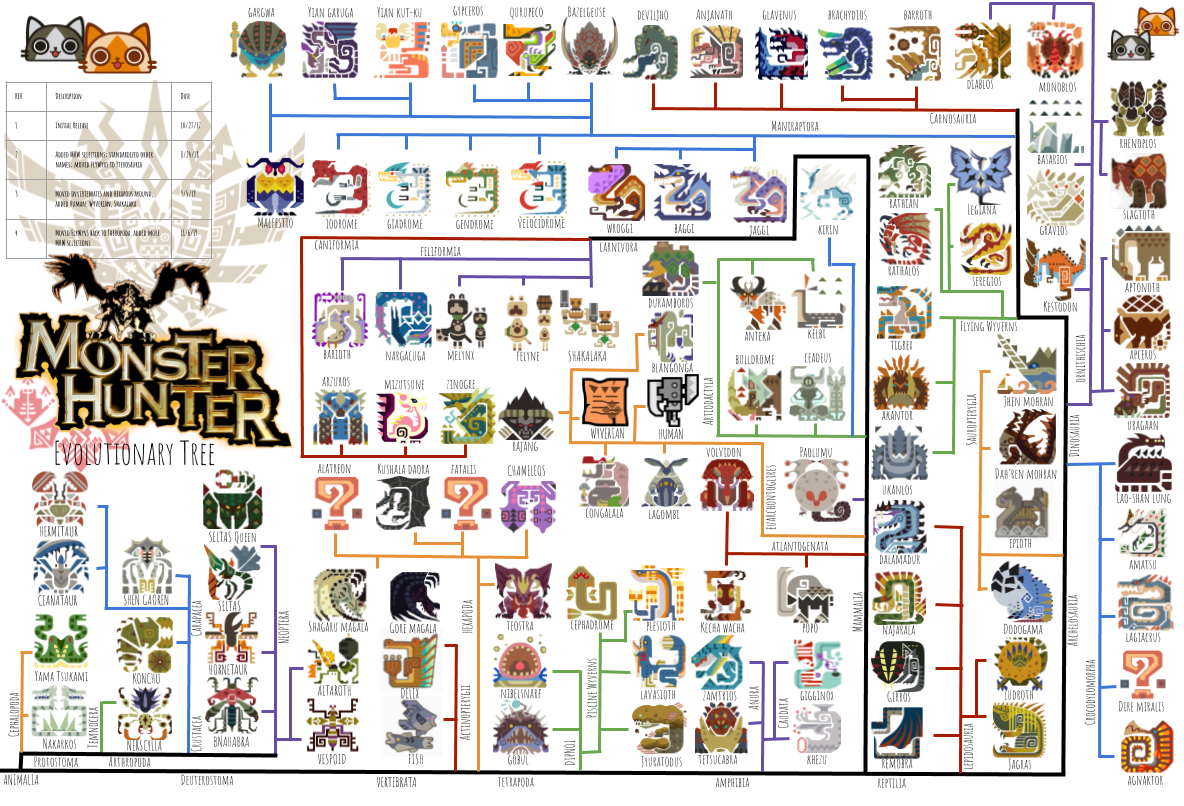

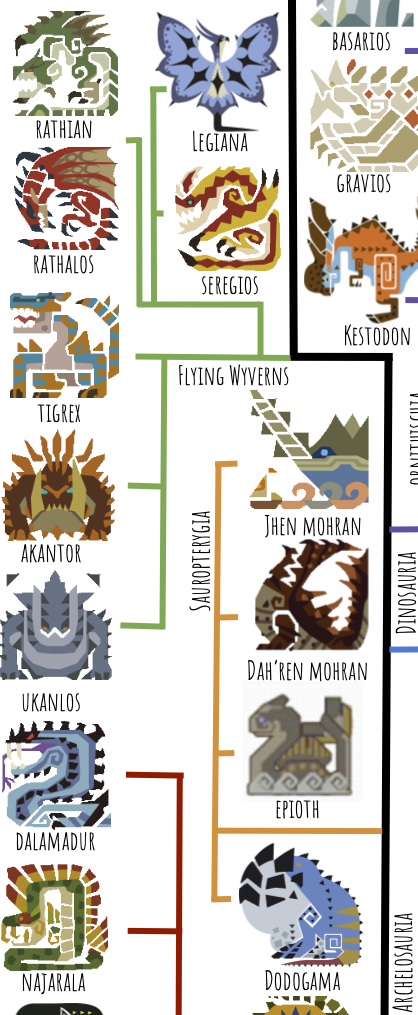

In this post, I’ll show you the tree of life I’ve created for select monsters in the Monster Hunter series, and go over some of what the last common ancestor of various groups may have looked like. Keep in mind that these are fictional creatures that the creators didn’t intend to have evolved in any realistic way; this is just my attempt at imagining how they might have arisen given a realistic evolutionary framework. You are free to disagree with my opinions!

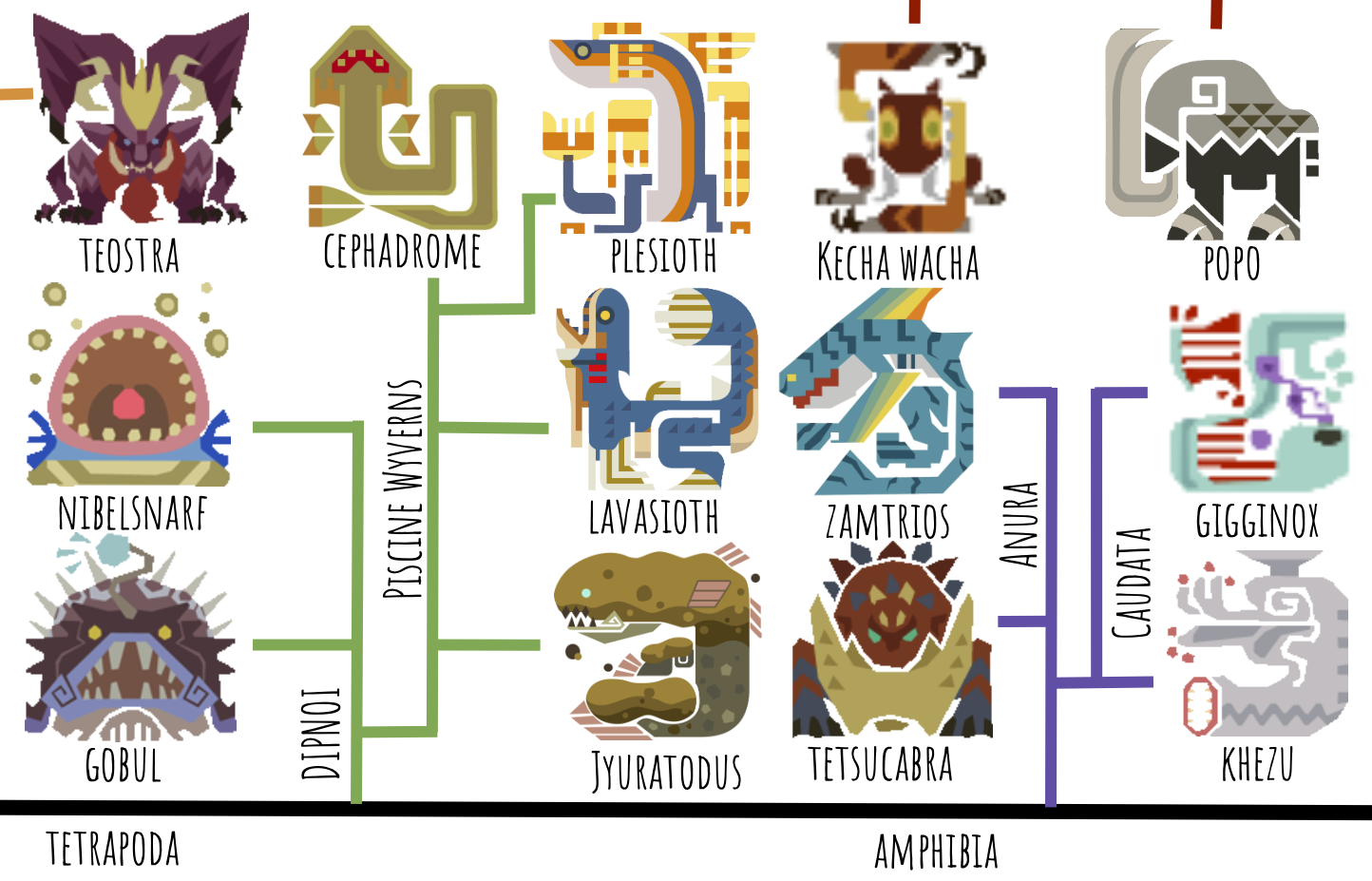

Okay, without further ado, here’s the tree:

Sorry for the low resolution; keep reading to see detailed views of various sections of the tree.

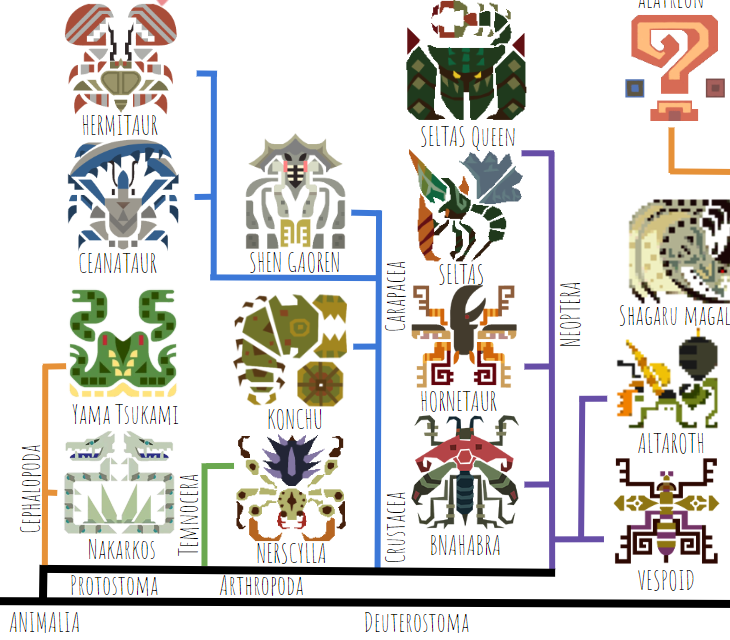

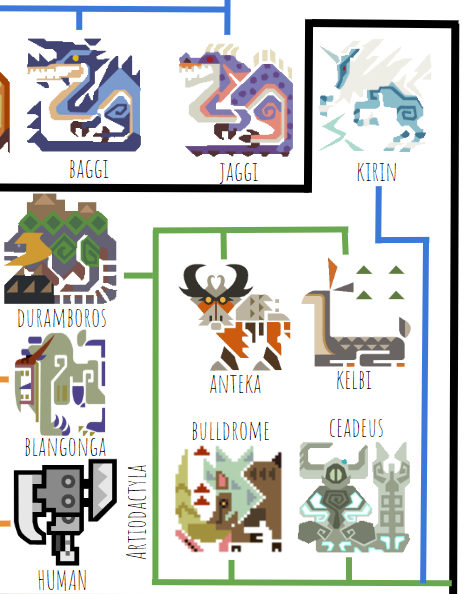

I’ve started with a structure that’s pretty similar to our real-world tree of life. The first group to branch off are the protostomes, including arthropods and cephalopods. Protostomes include most invertebrates, and together with the deuterostomes (ecinoderms like sea stars and sea cucumbers, plus all vertebrates) make up the clade Bilateria, or animals with bilateral symmetry. The protostomes of the Monster Hunter universe include Nerscylla, Seltas, Shen Gaoren, Yama Tsukami, etc:

Officially, Konchu is a neopteran, but here I’ve included it as a basal carapaceon (the group including Hermitaur, Ceanataur, and Shen Gaoren) due to its similarity to pillbugs, which are crustaceans. Funnily, Neoptera is a real-world clade that actually would include all the animals that are included on this tree (beetles, ants, and wasps). Ants and wasps are more closely related to one another than they are to beetles, in the group Hymenoptera (name not shown).

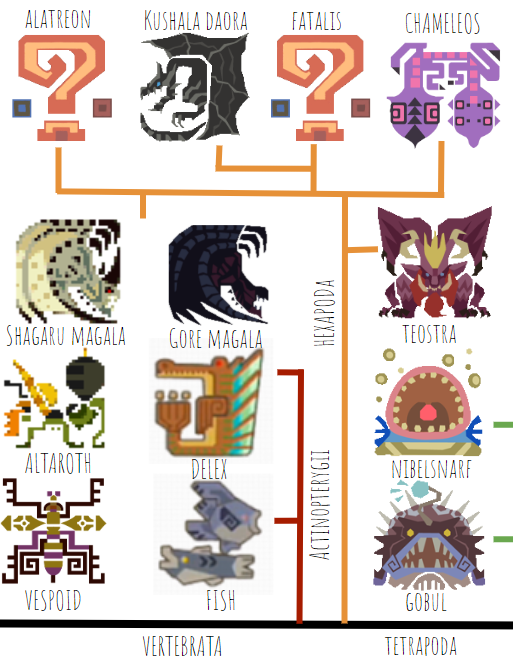

The next groups we’ll look at are the ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii) including Delex and, well, fish, and the Hexapoda, or six-limbed vertebrates, most of which are Elder Dragons.

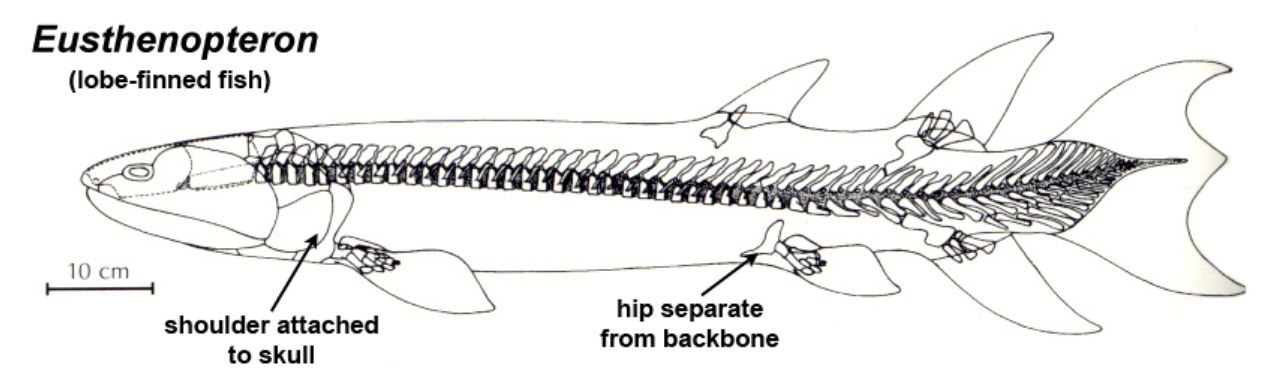

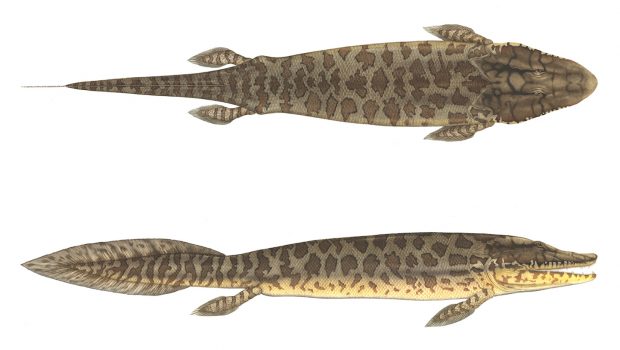

The assumption I’m making here is that, similarly to in the real world, lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) split off from the ray-finned fish, but instead of lobe-finned fish giving rise to the tetrapods, in Monster Hunter they split into two groups, the Tetrapods and Hexapods*. Some real-life early lobe-finned fish had bones in more than four of their fins, like Eusthenopteron:

Maybe a group of these fish kept all their limb-bones as they developed into land-faring creatures parallel to the tetrapods:

From there, the first Hexapod to split off is Teostra (and Lunastra, not shown) because of their similarity to stem-mammals (whether this assumption is a good one is debatable). Teostra has fur in some places, scales in others, and has an upright posture. Next, among the reptilian Hexapods, the most basal is Chameleos, based on its lack of derived features–it doesn’t have feathers, and has a more sprawling posture than other Elder Dragons. Then, Kushala and Fatalis are closely related, based on their wing morphology–both have the thumbclaw free and the other four fingers supporting the wing. Magala and Alatreon are also related through wing morphology–Magala has four claws free and only one elongated finger supporting the wing along with an elbow spike, while Alatreon has three claws somewhat free and two supporting the wing. Perhaps Magala’s wing is more derived, as its ancestors used the wing more and more for maneuvering on the ground.

One thing to note about this tree is that it doesn’t show evolutionary distance. There are not very many hexapodal Elder Dragons in Monster Hunter compared to tetrapodal monsters, so I’m able to cram the hexapods into a relatively small area on the tree, even though they’d likely be only distantly related to one another. The orange line splitting off the main black line before reaching Teostra should likely be way, way longer. And the line splitting off this line and going toward Teostra should also be pretty long. But I don’t have room for that on this tree.

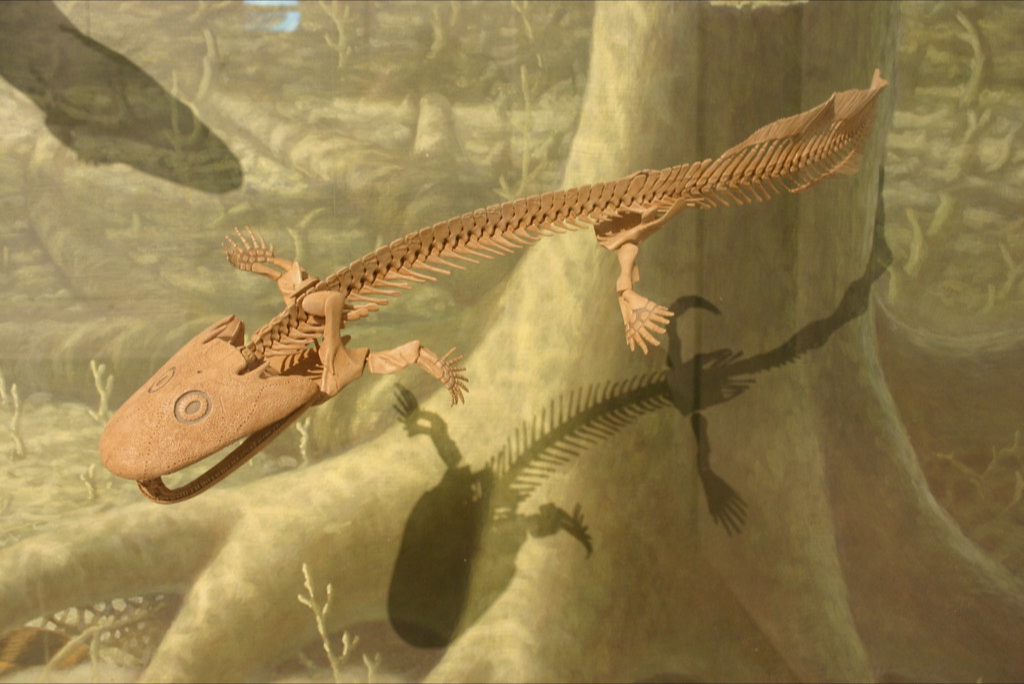

Another strange thing to think about is why all Monster Hunter’s hexapods have four legs and two wings. Presumably, six legs would have evolved first, like the salamander pictured above, and then two would have been repurposed into wings later. That means that six legs would’ve had to have been useful at some point in its own right, or it wouldn’t’ve been selected for–evolution never does anything in preparation for doing something useful later, unless the former thing is useful now. The fact that six legs had to have been useful makes it seem unlikely that all six-legged hexapods would have subsequently died out, leaving only the winged ones. So…Capcom, can you please include a six-legged Elder Dragon in the next generation? Thanks in advance.

*Hexapoda is a real taxonomic clade containing insects. But here I use it as a sister clade to Tetrapoda, containing six-limbed vertebrates.

Now we move to the next part of the tree, the basal tetrapods:

Like in the real world, the first group to split are the lungfish, or Dipnoi. In Monster Hunter, this not only includes the monsters similar to real early fishapods–Gobul and Nibelsnarf–but also the very strange, derived Piscine Wyverns. These are all in a clade together because of their unclear number of digits on each limb–Piscine Wyverns appear to have fishlike fins, not dissimilar to real-life “fishapod” Tiktaalik:

Jyuratodus, a new addition to the Piscine Wyvern roster from Monster Hunter World, is the most basal; it very much resembles a lungfish, and its name is derived from Ceratodus, a real-world genus of Mesozoic lungfish. I feel like Capcom created this monster specifically to tie the Piscine Wyverns to the Leviathans evolutionarily, which is pretty cool. Lavasioth is the next most basal, since its legs are more developed than Jyuratodus’s but its arms are still finlike. Plesioth comes next, followed by the highly derived Cephadrome, which is specialized for burrowing.

Gobul has similarly nondescript fins, while Nibelsnarf’s five short, unspecialized digits per limb, sort of like Acanthostega (below), lead me to place it in a more advanced position on the tree. Similarly to Acanthostega, Nibelsnarf can be considered an ancestral cousin to the rest of Tetrapoda, but not a direct ancestor–lobe fins evolved into digits many times among stem tetrapods.

Above: Acanthostega, a stem-tetrapod that had eight digits per foot! That’s way too many digits.

To be honest, Piscine Wyverns are my least favorite monsters in the series. They look the least believable to me. (And the underwater maneuvering to dodge Plesioth’s waterjet attack was always unreliable–I’d always dodge frontward or backward instead of up out of the attack plane. Irritating. But maybe I’m just bad.)

Moving on, we have the true amphibians, with Anura (frogs) on one side, including Tetsucabra and Zamtrios, and the Caudata (salamanders) on the other, including Khezu and Gigginox. At first, it seems like a bit of a leap to call Khezu and Gigginox amphibians, especially due to their possible jawlessness (in the real world, there’s no such thing as a jawless tetrapod–fish developed jaws first, before developing limbs). But when Khezu “smiles” in-game, its mouth does appear to close like it has a jaw, and it bears a very strong resemblance to a giant caecilian (a real legless amphibian).

Above: a caecilian’s horrifying maw. I wouldn’t be surprised if the designer of Khezu was directly inspired by these tiny terrors.

Here I’ve placed Khezu as more basal than Gigginox, which not only seems to have some sort of derived jaw adaptation optimized for clinging to ceilings, but also has gecko-like fingers for climbing and bioluminescence, both of which seem to be derived traits. I’m thinking Gigginox has a jaw similar to that of cookie-cutter sharks, which use their lips to suction onto large animals and their band-saw-like teeth to chop out a neat cylinder of flesh.

Above: A cookie-cutter shark’s mouth, or how one repurposes a jaw for a jawless lifestyle.

Mammals

Now we’ve reached the more advanced tetrapods, the amniotes (reptiles and mammals). Let’s explore the mammal side first.

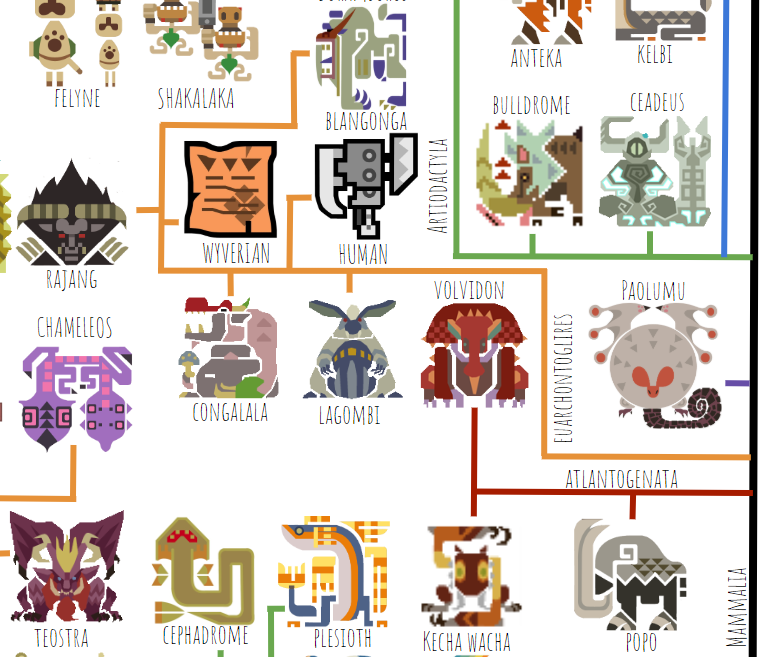

There don’t seem to be any marsupials in the Monster Hunter universe, which makes the mammal tree much more compact. As in real life, the first group of placental mammals to diverge from the rest are the Atlantogenata, which includes proboscideans (Popo), sloths (I’m calling Kecha Wacha a sloth here), and armadillos (Volvidon). As in real life, sloths and armadillos are more closely related to one another and occupy a group called Xenarthra (name not shown). Kecha is a very chimera-like animal, unusual for Monster Hunter, and is thus hard to place on this tree. It has a proboscis like an elephant or tapir, gliding membranes like a flying squirrel or colugo, and claws specialized for suspensory behavior like a sloth. Since proboscises and gliding membranes are independently present among multiple groups of real-world living mammals but sloth-like suspensory claws are not, I decided Kecha was probably a highly derived sloth.

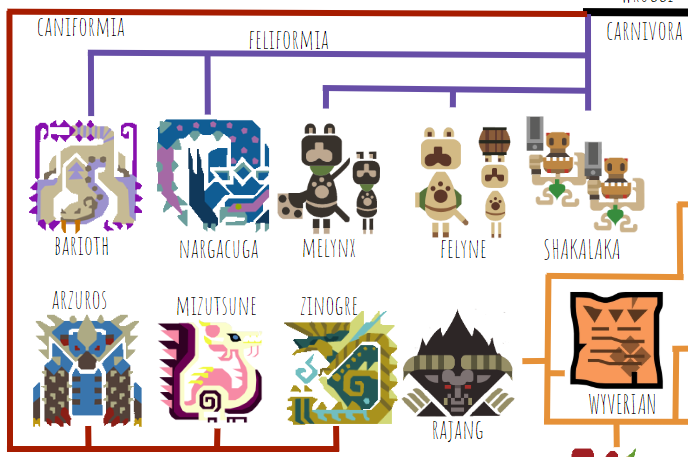

Next we have the euarchontoglires, a group that in real life includes rodents, primates, and their close relatives. The only glire (rodent-relative) present in Monster Hunter (at least in America; there’s a Japanese release that has some kind of big capybara you can fight) is Lagombi, a bear-sized rabbit. An argument could be made that it’s more likely that a bear secondarily evolved long ears and a rabbitlike face, but I think Capcom intended Lagombi to be a giant rabbit, so that’s where I’m placing it. The other monsters on this branch are the primates, including Congalala, Blangonga, Rajang, humans, and Wyverians. The strange thing is that Congalala, Blangonga, Rajang, and Wyverians are all digitigrade in their back feet, while real-world primates are plantigrade. This is a major restructuring of the primate leg, indicating that basal primates probably looked very different in Monster Hunter than they did in the real world, and that humans are only distantly related to extant primate species.

Onward! Here we take a look at the laurasiatherians:

In the real world, Laurasiatheria includes bats, ungulates (hoofed animals), and carnivores (cats, dogs, and relatives). Paolumu, the only bat in the MH universe, is different than real bats in that it displays zygodactyly, where each foot has two toes facing forward and two facing backward, like a parrot. Fortunately for Capcom, zygodactyly evolved several times among birds independently, which means it’s not too hard to do (at least for birds), so it’s not too implausible for a bat to have evolved zygodactyly as well. Paolumu’s wings are similar to real bats’, with the thumbclaw sticking out and the other four fingers elongated to support the wing membrane.

The next group to branch off is Ungulata, which quickly splits again into Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates, including horses, rhinos, and tapirs) and Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates, including all other hoofed animals, hippos, and whales). The only perissodactyl is Kirin; the artiodactyls include Ceadeus, Duramboros, and the monsters that are pigs, deer, and elk by another name. One thing Capcom could do better is investing a little more design energy into small monsters–they tend to be much more derivative than the large ones.

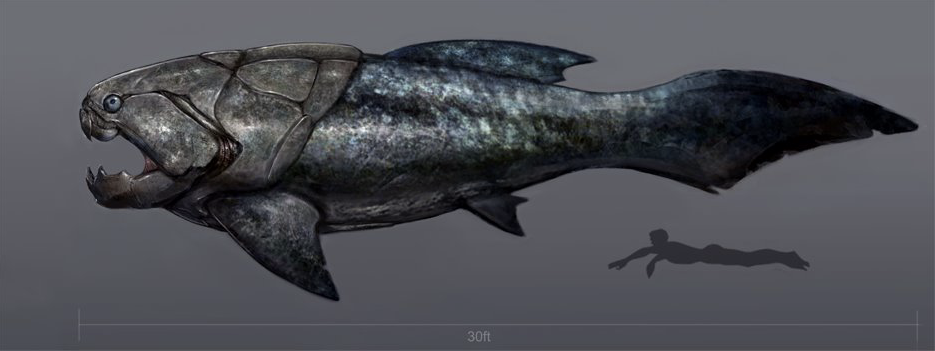

Ceadeus is a particularly interesting case, since it has unusual bony plates on its face reminiscent of predatory placoderms like Dunkleosteus:

But Ceadeus has fur, horns, and a horizontal tail fluke*, indicating that it’s probably a secondarily aquatic mammal rather than a placoderm descendant that split off way before. That means Ceadeus must have evolved its bony head plates independently. I don’t think this is particularly plausible, but given that whales are already such derived artiodactyls, I’ll give Capcom the benefit of the doubt.

*Non-tetrapod fish and secondarily aquatic reptiles swim with a side-to-side motion and have vertical tail fins. Secondarily aquatic mammals swim with an up-and-down (dolphin-kicking) motion and thus have horizontal tail fins.

Next up we have the carnivorans:

This part of the tree is pretty straightforward and parallel to the real world. We have the feliforms (catlike carnivorans), including Narga, Barioth, Felyne, Melynx, and Shakalaka, and we have the caniforms (doglike carnivorans), including Arzuros, Mizu, and Zin. The interesting thing about this section of the tree is the presence of another group of sentient animals, the Felyne branch. They have to have evolved intelligence and bipedalism independently from humans and Wyverians, since they’re separated by many non-sentient, quadrupedal species on the tree, which is not implausible. I’ve tentatively put the Shakalaka on the same branch as the Felynes because the games officially classify them as Lynians, but judging by their plantigrady and hairlessness, they may actually be primates closely related to humans. It’s hard to tell, given we never see their faces.

Reptiles

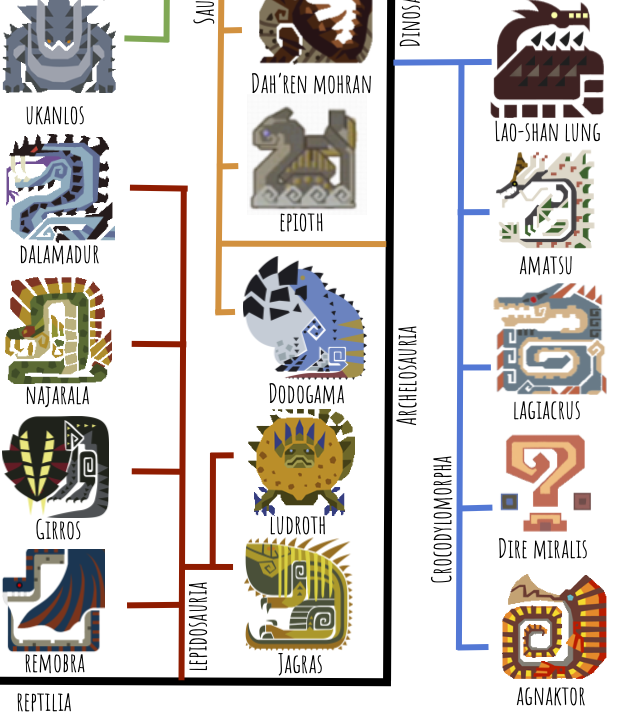

We’ve made it to the reptile side of the tree! Let’s start with a look at the reptiles not in the Pan-Aves group:

First we have the lepidosaurs, or lizards and snakes. This includes Jagras, Ludroth, Remobra, Girros, Naja, and Dala. Ludroth is cool because they’re very close to what basal mosasauroids looked like–semiaquatic monitor lizards in the process of fully committing to an aquatic lifestyle:

Above: Aigialosaurus, a basal mosasauroid from the early Late Cretaceous.

Both snakelike wyverns retain small clawed limbs, which I think is also cool, since this is how real-world snakes looked before they lost their legs entirely (though much, much smaller):

Najash, a Cretaceous basal snake. Probably what Najarala is named after. Look at those tiny legs! Dalamadur is in a more derived position on the tree because its limbs are more reduced than Najarala’s.

I’ve included Remobra as a basal lepidosaur because (a) their heads and teeth are so snakelike, (b) there is a precedent for gliding lepidosaurs, so maybe Remobra is a derived form capable of powered flight, and (c) the Monster List calls them Snake Wyverns, along with Najarala.

Draco, a real-life gliding lizard. Its “wings” aren’t attached to its arms, but are actually part of its ribs! In the photo, it’s actively grabbing the wings with its arms to steer. I’d imagine Remobra is probably more distantly related to other lizards than Draco is, given how advanced Remobra’s wings are.

At least with the Lepidosaur group, it looks like Capcom took a lot of inspiration from evolutionary history! Awesome.

Next up are the Pantestudines, or “all turtles,” which in real life include Testudines (turtles) and Sauropterygia (plesiosaurs and pliosaurs):

I’ve put Dodogama here as a basal turtle because its toothless beak and barrel chest remind me of real-life proto-turtles like Eunotosaurus:

I’m not a fan of the Monster List category “Fanged Wyvern”. The only thing in this category before World was Zinogre, which is based on a wolf; in World, Capcom introduced a bunch of quadrupedal reptiles that also are considered Fanged Wyverns. It seems like the monster version of a wastebasket taxon–anything that doesn’t fit the existing categories is lumped in here.

Moving on, we have one Plesiosaur, Epioth. With its clawed flippers and long hind legs, it looks like a more basal plesiosaur on its way to becoming more specialized for its aquatic lifestyle. Two interesting things about Epioth: it’s covered in fins, and it has specialized strong middle digit on each front and back leg. Regarding the tail fins, real-life Plesiosaurs didn’t have any, instead having a stiff body and reduced tail, and using the flippers for propulsion like a sea turtle. But it’s not tough to imagine Epioth’s body plan being selected for–in fact, it looks like probably a better swimmer than plesiosaurs. Maybe this somehow has to do with the fact that Epioth is herbivorous, while plesiosaurs hunted fish? The second interesting thing, the special middle digit, is super weird to me. Why did Capcom bother including such a detail, that was probably more difficult to render than just a fin? The artist must have had an idea what this claw was used for. Digging for clams, sort of like an aye-aye? Defense, like an iguanodont? Cutting marine vegetation, like an aquatic therizinosaur or panda? Nothing super sticks out as the right answer to me, but it’s interesting to think about.

Next we have Jhen and Dah’ren, or what it would look like if pliosaurs got to be the size of whales…and three or four times larger. Apparently Jhen is 366 feet long; blue whales are 100 feet. Megalodon, an extinct giant shark, and Livyatan, a giant extinct sperm whale, could get to 60 feet. The largest known sauropods, the South American titanosaurs such as Patagotitan, were 120 feet long, but most of that was neck and tail.

You probably know that the blue whale is the largest animal to ever live, and it’s even heavier than the largest sauropods (isn’t that pretty cool, that we inhabit the earth at the same time as the largest animal ever?). What allowed whales to get this huge, all of a sudden, and what prevented them from attaining these sizes in the past? Giant marine carnivores, or the lack thereof. In the past, there’s always been some kind of giant marine apex predator that provided selection pressure for its prey to be small, fast, and maneuverable. When the last of these giant marine predators, Megalodon, went extinct around 3.6 million years ago, it provided an opening for other animals to get big. Maybe something similar happened to Jhen and Dah’ren. Except they swim through sand, not water, which doesn’t really have the same buoyant properties unless it’s liquefacting, which it doesn’t seem to be whenever you, the hunter, stand on it. Maybe Monster Hunter’s sand-swimming creatures somehow emit subsonic sound waves that locally liquefact the sand or something…or maybe it’s just a cool gameplay mechanic where you can let the monster move fluidly without subjecting the hunter to unwieldy swimming gameplay.

Next, let’s talk about the crocodylians. Lao-Shan, Amatsu, Lagi, and Miralis are all very similar (excusing Lao-Shan’s ridiculous size), assuming Miralis’s shoulder cannons are specialized osteoderms or horns and not additional limbs. Agnaktor is the most derived, with its beak and sail. The beak points to a possible herbivorous or piscivorous lifestyle–maybe volcanic Agnaktor is herbivorous or omnivorous, and Glacial Agnaktor is piscivorous. Either way, they’re one of the monsters that won’t touch any meat you lay down, which I think is a cool detail.

How does Amatsu manage to fly? Lighter-than-air gas sacs? Magnetism? Electromagnetism? As far as we know, no real animal uses the first two things to fly, but “ballooning” spiders actually use electromagnetism to take off, by building up static charge in their web-balloons. Maybe Amatsu does something similar with all its finny bits. We know that Lagi, which is closely related, has electricity-producing organs, so maybe Amatsu does as well.

We’ve made it to the dinosaur portion of the tree! Before going into the Flying Wyverns (which are a branch of Theropoda that doesn’t exist in the real world), let’s talk about the ornithischian dinosaurs:

The easy ones to place are Apceros, which is clearly an ankylosaur; Aptonoth, which is clearly an ornithopod; Rhenoplos and Slagtoth, which are clearly ceratopsians; and Kestodon, which is clearly a pachycephalosaur. Then we’ve got Uragaan. This guy is extremely enigmatic and could plausibly go in many places on the tree. Here I have it listed as a giant heterodontosaur because of its teeth–specialized molars and tusk-like canines, which aren’t found among saurischians. How did it come to eat rocks? I would speculate that its ancestors were herbivorous and consumed gastroliths to help it better digest tough vegetation, and then a mutation arose that allowed them to get nutrients from the gastroliths themselves. It’s also a bit unclear how, with its large brow-horns and gigantic chin, Uragaan is able to reach anything with its mouth–I’m pretty sure in-game its chin just no-clips through whatever is nearby when performing the eating animation.

Here I’ve placed Diablos and Monoblos as the most derived ceratopsians, who represent another instance of independently-evolved flight; they are herbivorous and their frills and horns are very classic ceratopsian. Gravios and Basarios are also marginocephalians, but split off and evolved separately from the ceratopsians, yet again gaining flight independently.

Now for the theropods, starting with the Flying Wyverns. A case could be made that Flying Wyverns belong in Pterosauria, but I’ve put them in Theropoda because of their grasping, birdlike feet (real-life pterosaurs had plantigrade, walking feet).

The Monster List claims Tigrex is a basal Flying Wyvern and that Akantor and Ukanlos are secondarily flightless members of this same tree. This seems plausible enough, so I’ve accepted this Word of God as is. Note that this group has wings that have three fingers free and support the wing with an elongated and fused fourth and fifth finger.

The next group is the Raths, Seregios, and Legiana. I’ve grouped these due to their wing morphology–the thumbclaw is free and the rest of the wing is supported by the other four fingers, like a bat. Seregios has somehow acquired a second thumbclaw, for a total of six fingers, presumably made out of one of the wrist bones like a panda’s second thumb:

Seregios has also become independently zygodactyl, like Paolumu, while the Raths are anisodactyl, meaning they have three toes pointing forward and one pointing backward.

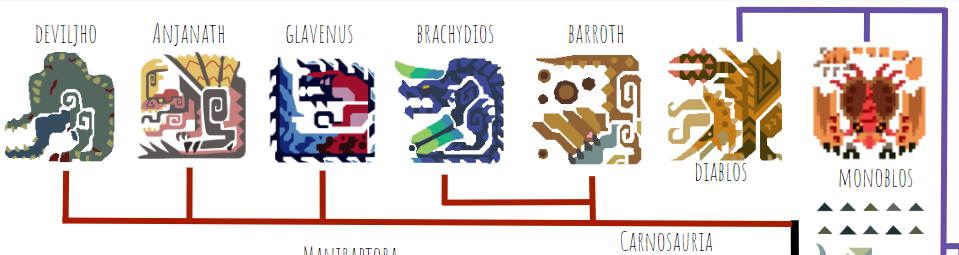

Here are some more derived theropods, the carnosaurs:

In real life this is a paraphyletic group, but here I’ve drawn it as monophyletic. Barroth and Brachydios are closely related armored theropods that retain the use of their arms. The other three have highly reduced arms, especially Deviljho. Anjanath is the only one on this branch with feathers, but as in the real world I’m assuming that feathers are the archosaurian ancestral condition and many derived groups independently lost them when they became larger-bodied and needed less insulation. This is corroborated by the fact that Rathian, an archosaur relatively far from Anjanath on tree, has quill-like feathers on her shoulders and wrists.

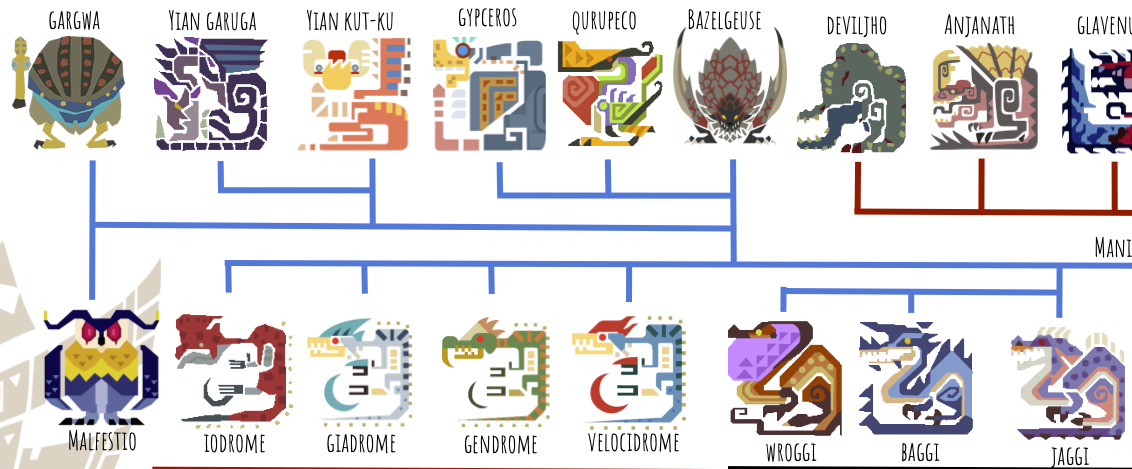

And finally, the maniraptors:

Jaggi, Baggi, and Wroggi are obviously closely related, maybe as a parallel to the real-life Megaraptorans, a clade that we still don’t really know where it belongs. An argument could be made that Wroggi is actually an amphibian that convergently evolved a theropod-like body plan, since it looks slimy and seems to be able to produce toxins, which no birds (and probably no maniraptorans) are known to be able to do. However, some real-life birds feed on toxic substances and then “sequester” the poison in their skin, such as the pitohui and the little shrikethrush, so maybe Wroggi does this too. Wroggi also has a scaly underside, indicating that maybe the scales on its back are just too small to see or render.

The ‘dromes are clearly analogues to real-world dromaeosaurs, since they share both part of their name and the “killing claw” on each foot. Fun fact, “drome” means “runner” in Greek. So Velocidrome means “swift runner”. One of the few monsters that has a name that could actually belong to a dinosaur or something!

Similarly to Wroggi, a case could be made that Iodrome is an amphibian because it appears slimy and spits poison–but this is a much worse case, given that Iodrome lives in the Volcano, where if it were an amphibian, its anamniotic eggs would dry out and die. Plus, the Monster List calls it a Bird Wyvern, so we’ll go with that here.

The last group we have to cover is the paravians. Gypceros (another apparently poisonous maniraptoran) supports its wing with three fingers, with the thumbclaw free; one finger appears to have been lost or reduced. It also still has teeth in its beak, leading me to place it at the basal-most position among the paravians. Qurupeco and Bazelgeuse have lost all but two of their fingers, and also have teeth in their beaks.

Yian Kut-Ku and Yian Garuga have very confusing wings, which appear to be supported by one elongated finger and a bunch of non-finger “styliform” bones. These aren’t unheard of in the real world, as evidenced by the unusual paravian dinosaur Yi:

And finally we have Gargwa and Malfestio, two of the very few true avialan birds in the Monster List.

Thanks for bearing with me on this extremely long journey into the bowels of Monster Hunter lore. Hope you enjoyed. Feel free to email me with any comments, opinions, or suggestions on my phylogenetic analysis of this awesome game series!

Image credits: Page image Monster Hunter Claw Eusthenopteron Six-Legged Salamander Tiktaalik Acanthostega Dunkleosteus Aigialosaurus Najash Draco Eunotosaurus Panda Thumb Yi Qi