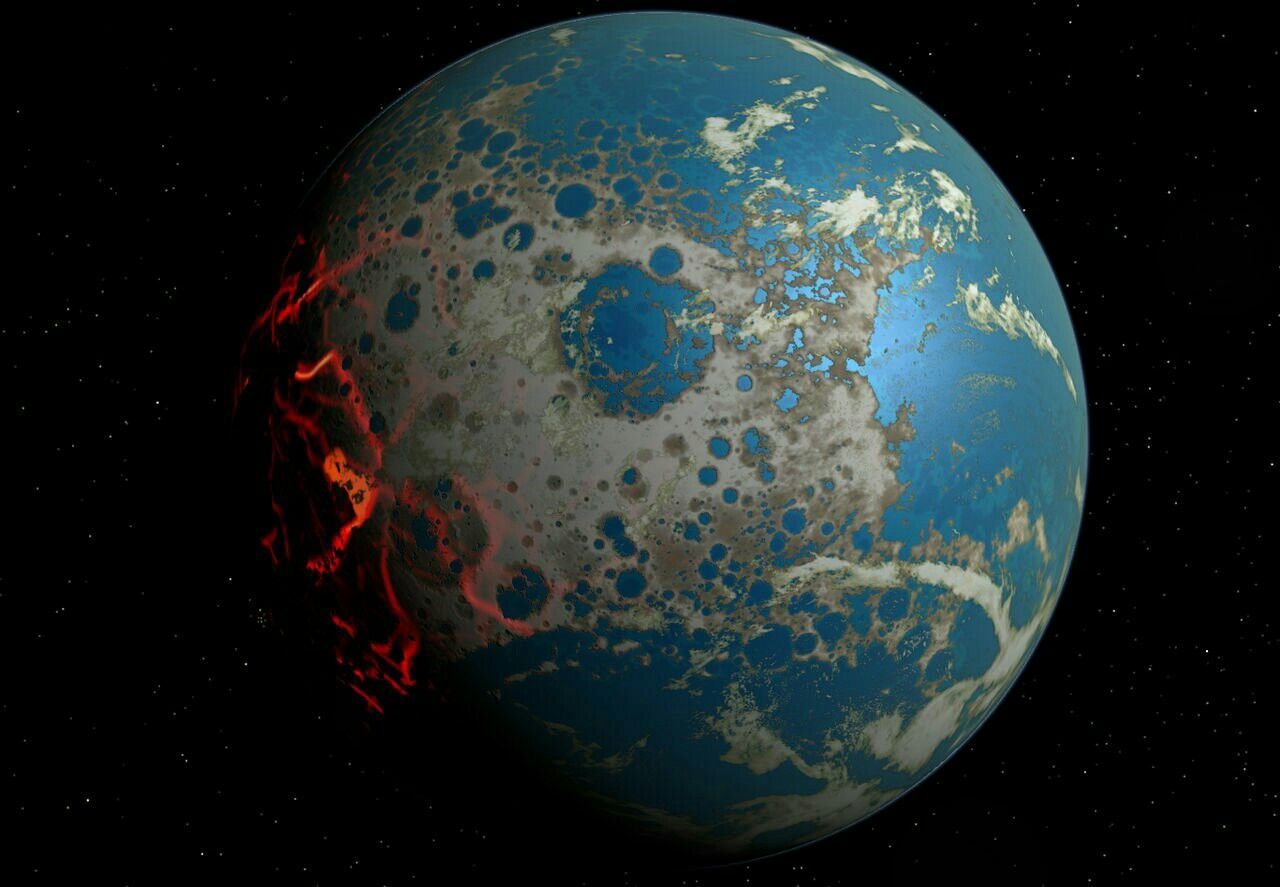

The earth formed out of colliding space debris 4.54 billion years ago, and a mere 260 million years later (or less), there was life. It took another 2.43 billion years (nine times as long!) before there were eukaryotes, or single-celled organisms with nuclei and organelles, like an amoeba. That seems to indicate that simple life forms easily, while the task of turning that simple life into complex life–even the simplest kind of complex life–is much more difficult.

How did life form so quickly out of non-life? The dominant theory is called the RNA World Hypothesis. This postulates that the first things that were able to replicate themselves were just free-floating strands of RNA, which competed with each other for resources and thus kicked off the process of natural selection. In this blog post, I’ll explain the mechanism by which RNA molecules form and replicate, and how we think they gave rise to life as we know it.

What is RNA?

RNA stands for Ribonucleic Acid. In the right conditions, which were present on early earth (specific levels of heat, salinity, and available chemicals), RNA just forms spontaneously. It is a close cousin to DNA, but DNA is a double-stranded molecule while RNA is just one strand. This will become important later.

Both RNA and DNA are made up of sequences of building block molecules called nucleotides. Individual nucleotides are shaped sort of like a T, with a “backbone” forming the top bar of the T that is the same between all nucleotides, and a “base” forming the vertical stroke, which is different between each type. There are four types of nucleotides in RNA, adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and uracil (U). Their backbones can stick to any other nucleotide, forming long strands that look like this: TTTTTTTTTT, with any nucleotide in any location along the strand. This allows for many different permutations of nucleotides along the strand–if you “read out” the nucleotides, one strand could read ACCCAUA, while another reads GGAGUCC.

While the backbone part of a nucleotide can bind to any other nucleotide’s backbone, the base portion is selective. A will only bind to U, while C will only bind to G. This is called base pairing, and means that in the right conditions (that is, a place with lots of free single nucleotides), a strand of RNA will attract the appropriate complementary bases and form a complementary strand. This complementary strand then acts as a template to form a copy of the original strand by attracting the appropriate free bases again.

Ribozymes

But that’s not life, that’s chemistry! Since any RNA strand can, in the right conditions, form a copy of itself, there’s no way for one strand to be a better replicator than another, and thus natural selection won’t work. How do we get from simple chemistry to competition and natural selection?

Here’s where it becomes important that RNA is naturally just a single strand. When there aren’t many free single nucleotides around, a strand of RNA can fold up and base pair to itself! Some of its open-ended bases will bind to others, while other open bases will be left partnerless. In this way, different sequences of RNA will fold up into different shapes and have different “sticky bases” available. Some of these outward-facing “sticky bases” can perform chemical reactions involving other free-floating molecules in the environment. A folded-up RNA strand like this is called a ribozyme. Usually, the reactions that randomly-generated ribozymes perform or catalyze will be equally random and not helpful to the ribozyme itself. However, given enough tries, eventually a ribozyme will form that is capable of streamlining the base-pairing process. These ribozymes have an advantage compared to other RNA strands when it comes time to unfold and replicate: it will be able to more effectively make copies of itself using its own complementary strand. In fact, this case is so special that this type of ribozyme has a special name: a replicase. It works by grabbing free nucleotides and attaching them to an existing RNA strand, which is much faster and less error-prone than waiting around for the right base pairs to float by.

However, other RNA strands can also benefit from this simply by being in the same area as a replicase. It’s not picky; it will grab any free RNA strand in the vicinity and create a complementary strand. How can it get rid of the moochers, and make sure it only copies its own complementary strand?

Membranes

Meanwhile, another type of molecule that just spontaneously forms is called a fatty acid. This is shaped sort of like a tadpole, with a polar “head” and a nonpolar “tail”. Polar things attract each other and repel nonpolar things, and vice versa*. Water is polar, so when individual fatty acids are floating around in water, they tend to form little spheres called micelles, with all the heads facing outward and the tails facing inward. If the micelle gets too big (by attracting more free fatty acids, which happens naturally over time) and there’s room for water in the center, a second layer of fatty acids forms with the heads facing inward. This sphere that is formed with water on both the inside and outside is called a vesicle. An important property of fatty acid membranes like this is that they are semipermeable, meaning that usually molecules on the inside can’t get out and molecules on the outside can’t get in, except sometimes under the right conditions, they can.**

What if a nucleotide-creating ribozyme ends up inside a vesicle? It will be able to keep the nucleotide-rich environment to itself, and replicate itself much more effectively! …Until it runs out of free nucleotides. This is why having a semipermeable membrane is important–it keeps the riffraff out (competitor RNA strands, being large, can’t fit through the membrane) but lets in the small raw materials needed to continue production.

*This is how soap works–it’s a molecule in the shape of a long chain with a polar end and a nonpolar end. Grease is nonpolar and water is polar, so without soap, water is ineffectual at rinsing off grease. When you add soap, the polar end sticks to the water and the nonpolar end sticks to the grease, and then the whole water-soap-grease unit rinses off together.

**Fatty acids frequently and spontaneously swap places between the inner and outer membranes. If a molecule on the outside is stuck to a fatty acid that happens to flip to the inner layer, the molecule may go with it and end up inside the vesicle.

Division

Now all that’s left to do is divide the cell. Luckily, this also happens spontaneously!

As the vesicle gets bigger and bigger, by attracting more free fatty acids, it gets unstable, and starts to wobble and stretch like a figure-eight. Eventually, it pinches off in the middle, forming two smaller vesicles, with a random amount of RNA on each side! This proto-cell isn’t a very good replicator, since it only produces approximate copies of itself, and relies entirely on random molecular collisions to function. How can it further improve its functionality?

There could be a second type of ribozyme inside the cell that creates nucleotides out of their constituent chemicals, and a third that creates fatty acids. That way, the cell doesn’t have to wait around for fatty acids and nucleotides to spontaneously form outside of itself and then collide with it; instead, it can manufacture its own components out of the raw materials that are much more abundant.

From there, the complexity ceiling is basically infinite–as you’ve probably noticed, being a complex organism made of cells yourself.

Mutations

There’s one last detail to address before we can confirm that this proto-cell is in fact alive. Natural selection requires variation to work–if a replicating proto-cell can only produce exact copies of itself, it can’t ever improve, which means it can’t evolve. How could this proto-cell give rise to all the complex forms of life that we know today?

Luckily, RNA replication is not an error-free process. Sometimes, an A will slip in where there was once a G, changing how the resulting strand folds, and thus changing its functionality. As with all mutations, this is usually neutral, and often bad, but occasionally a mutation that has a beneficial effect will occur–for example, a ribozyme that is more efficient at its job. Then, the proto-cell armed with this new ribozyme will out-compete the other proto-cells for resources and will replicate itself more often. That’s natural selection! This spontaneously-formed proto-cell is a living thing!