I was inspired by Ceri Thomas’s awesome paleoart blog, Nix Draws Stuff, which did a dinosaur “alphabestiary” a few years ago. Here is my own attempt at one dinosaur per letter per day. Some of them are even animated. Enjoy!

A is for Animantarx

Animantarx (meaning “living fortress”) was a smallish nodosaur from early Late Cretaceous Utah. Nodosaurs were the armored ones that did not have tail weapons, while ankylosaurs were the ones that did. From this angle, I can really see how they’re related to stegosaurs (both ankylosaurs and stegosaurs are in the family Thyreophora). Ankylosaurs may have used their snoots to dig up roots and tubers. Originally this pose was intended to show that, but then I didn’t draw the dirt, so it just looks like he’s walking. Oh well, we know that ankylosaurs almost certainly did engage in walking.

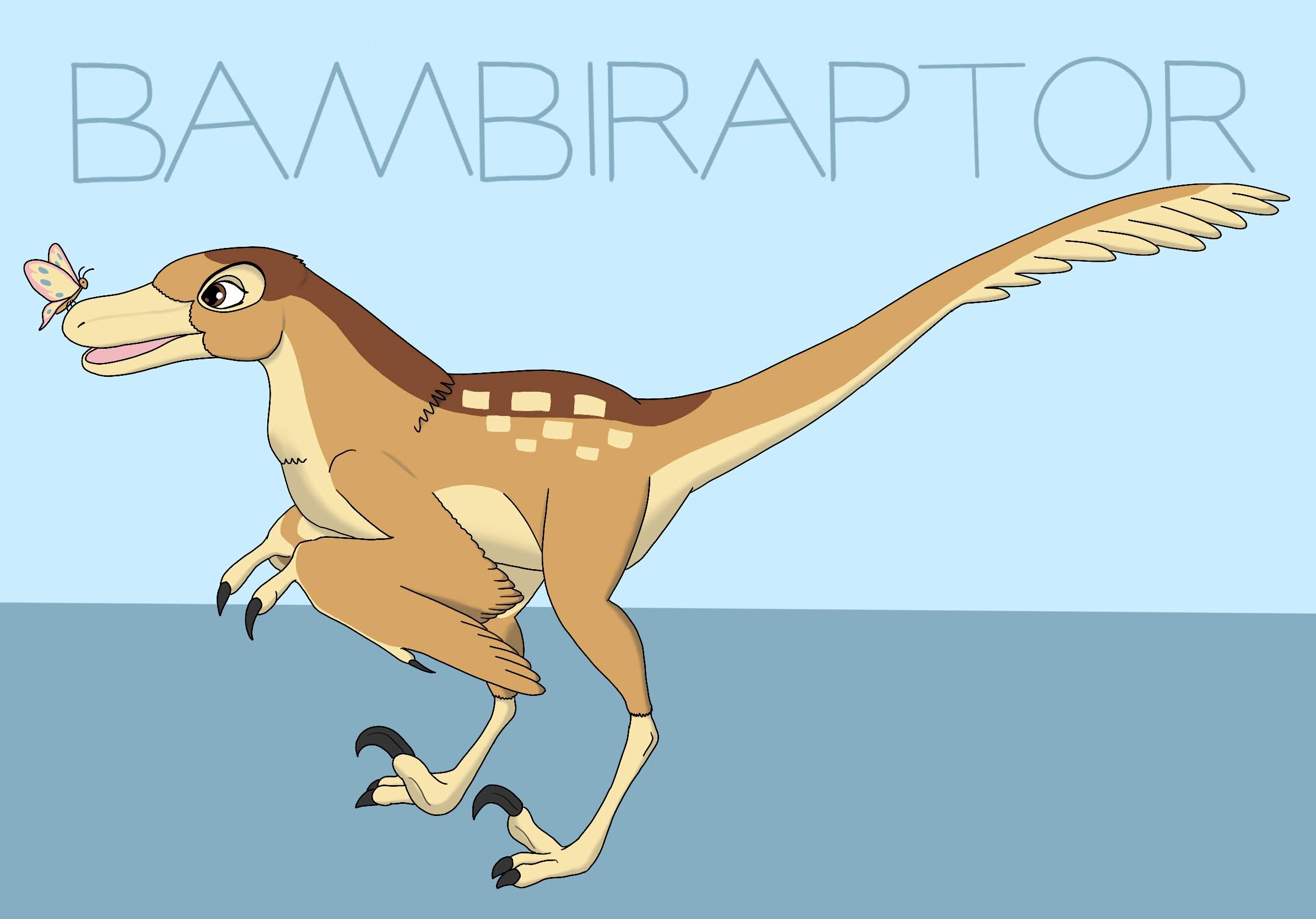

B is for Bambiraptor

Bambiraptor was a dromaeosaur from Late Cretaceous Montana. Yes, it is named after the Disney character. It is unusual in possibly having opposable thumbs, and arm flexibility that would’ve allowed it to put things in its mouth. Here, I’ve drawn it with its neck retracted and its feathers forming an “aeroshell,” disguising the neck’s true length. This is something modern birds do frequently. It’s also interacting with some kind of lepidopteran, which did exist at the time. Technically, we don’t know that Bambiraptor wasn’t colored like this.

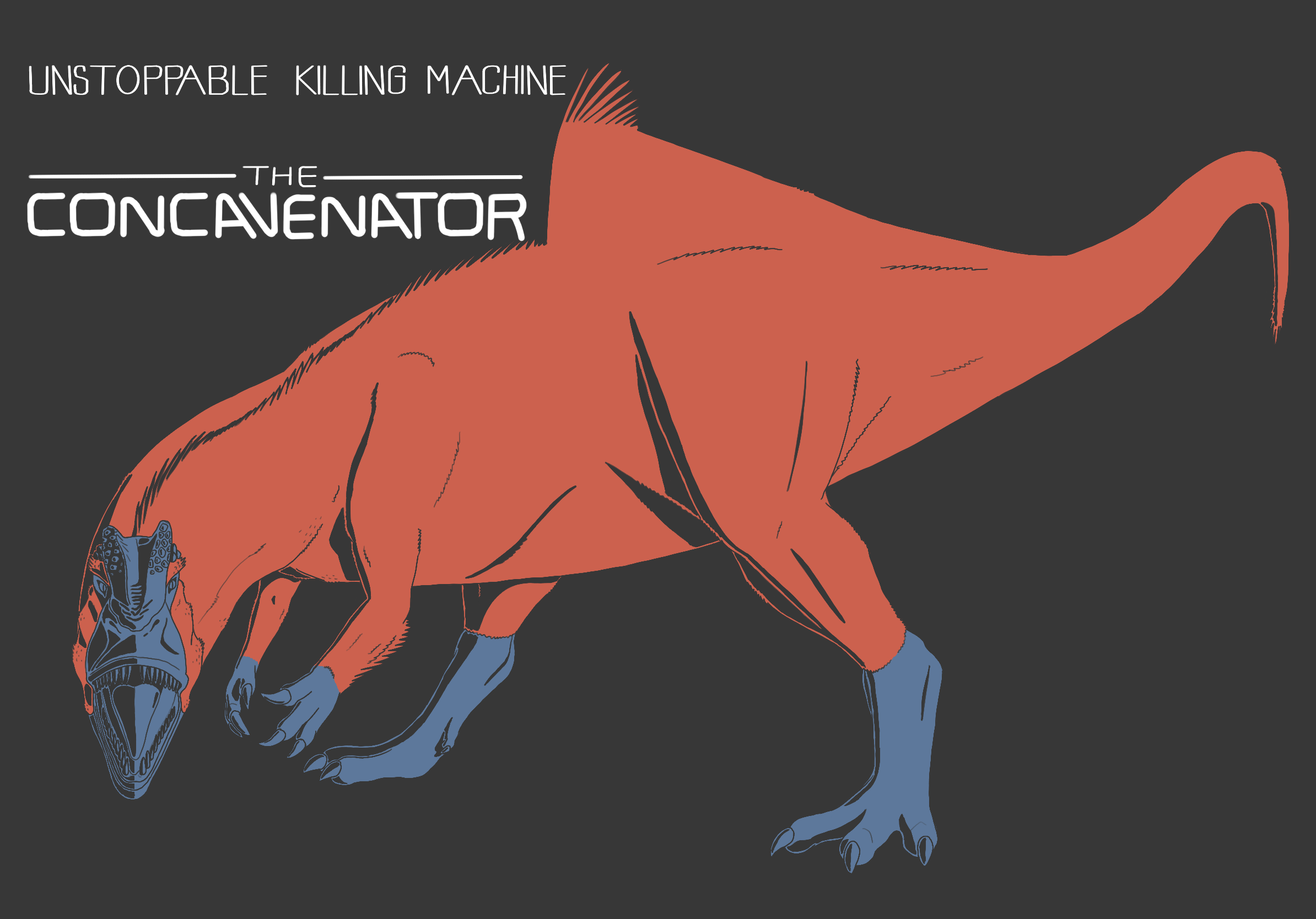

C is for Concavenator

Concavenator is supposed to mean Cuenca hunter, but to me it always looked like someone who will concave you. So here it is in the style of the retro Terminator movie poster.

Concavenator was a small carcharodontosaur (descendant of the earlier allosauroids) from Early Cretaceous Spain. It had two unusually tall neural spines on two of its vertebrae near the hips, indicating that it had some kind of sail or hump. Most sailed animals have way more than two vertebrae involved, so in comparison Concavenator’s sail is somewhat abrupt.

There’s a lot of debate about whether or not some bumps on Concavenator’s lower arm represent feather attachment points, but since the animal was smaller than Yutyrannus, I felt justified in giving it a full body feathering.

Drawing long-snouted creatures from the front is hard. I used a photo of a Carcharodontosaurus skull from this angle as reference, and it still turned out wonky.

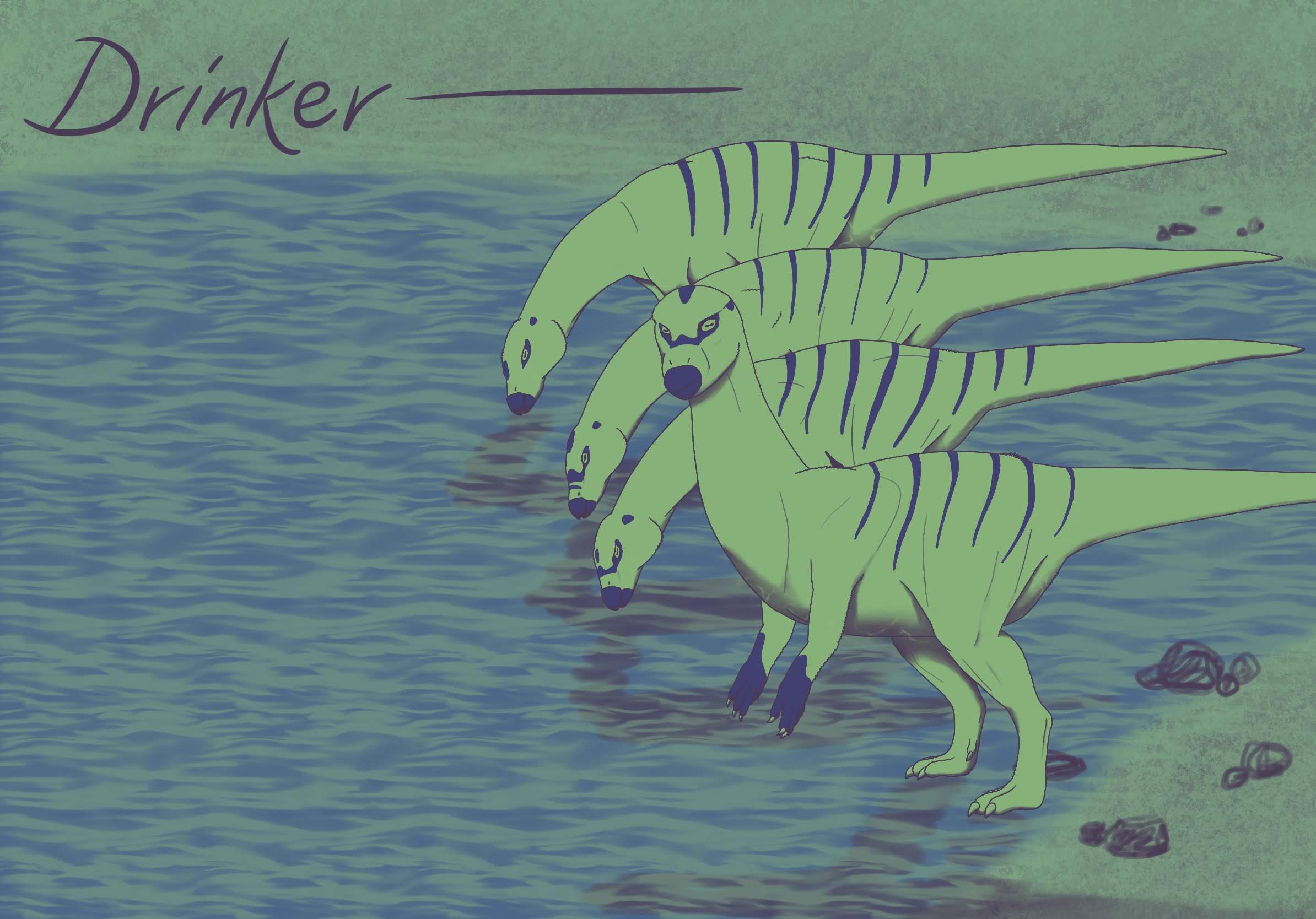

D is for Drinker

Actually, as of last year, the five genera Drinker, Othnielia, Othnielosaurus, Laosaurus, and Nanosaurus were all lumped under the banner of Nanosaurus, making the rest junior synonyms.

Nanosaurus was a small (20-pound) neornithischian from Late Jurassic North America. Its remains were originally found by the Bone Warrior, Othniel Charles Marsh (after whom Othnielia and Othnielosaurus were later named), while Drinker was named for his rival, Edward Drinker Cope, who did not find any Nanosaurus remains. These little beaked herbivores had a lacrimal bone in their skulls that gave them a perpetual angry look. Here, a herd of Nanosaurus drinks at a watering hole while one looks out for predators.

People often illustrate small neornithischians as being covered in quills, but since most modern animals aren’t quilly, I went with a shorthair look instead. I think my Nanosaurus ended up looking too bulky and muscular for how small they should be.

E is for Ekrixinatosaurus

Ekrixinatosaurus, meaning “explosion-born reptile,” was an abelisaur from Late Cretaceous Argentina. These were medium-sized, short-faced, long-legged, puny-armed theropods that were the dominant carnivores in the Southern Hemisphere at the time (tyrannosaurs ruled the Northern). Ekrixinatosaurus is called that because its holotype was discovered during explosive excavation for the laying of a gas pipeline–not because of something about volcanoes. (Volcanoes are a bit of a paleoart cliche.) Anyway, here’s Ekrixinatosaurus in the style of the 2014 Pompeii movie poster. I’m really happy with how the dinosaur itself turned out; less so with the background.

F is for Fruitadens (and Fruitafossor)

Fruitadens (meaning “Fruita’s tooth”) was a heterodontosaurid from Late Jurassic Colorado. It is the smallest-known ornithischian, at just under a foot long and weighing 1-2 pounds. Even so, it’s larger than the 2-ounce mammal, Fruitafossor (meaning “Fruita’s digger”). Fruitafossor had burly “Popeye arms” for digging, and anteater-like teeth specialized for crunching termites. Here, Fruitafossor defends its burrow in the roots of a yew-like tree from a Fruitadens that wandered too close, seeking the fallen false-fruit (true fruiting plants, angiosperms, didn’t exist yet). Fruit fruit fruit.

Heterodontosaurids were herbivores, but they had large tusk-like canine teeth, either for defense or for intraspecific competition. They also had lacrimal bones in their skulls that made them look really angry all the time.

G is for Gargoyleosaurus

Gargoylesaurus was a primitive nodosaur from Late Jurassic Wyoming, which lived in the shadow of the dominant tanky herbivores, the plate-backed stegosaurs (including the famous Stegosaurus). Ankylosaurs would later replace the stegosaurs in this niche in the Cretaceous period.

Since it’s named after gargoyles, which are decorative rain gutters, my Gargoyleosaurus is enjoying a heavy rainfall. What a moody boi. Remember, angiosperms including grasses, flowering, and fruiting plants, didn’t evolve until the Cretaceous period, which means all the plants in the background here are ferns, cycads, and conifers.

H is for Hexing

Hexing was a very small basal ornithomimosaur from Early Cretaceous China. Its name means “like a crane” in Mandarin and looks like the word “hex” in English, inspiring this picture of a flock of cranelike Hexing doing some kind of moonlight ritual. What sort of sound do you think they’re making?

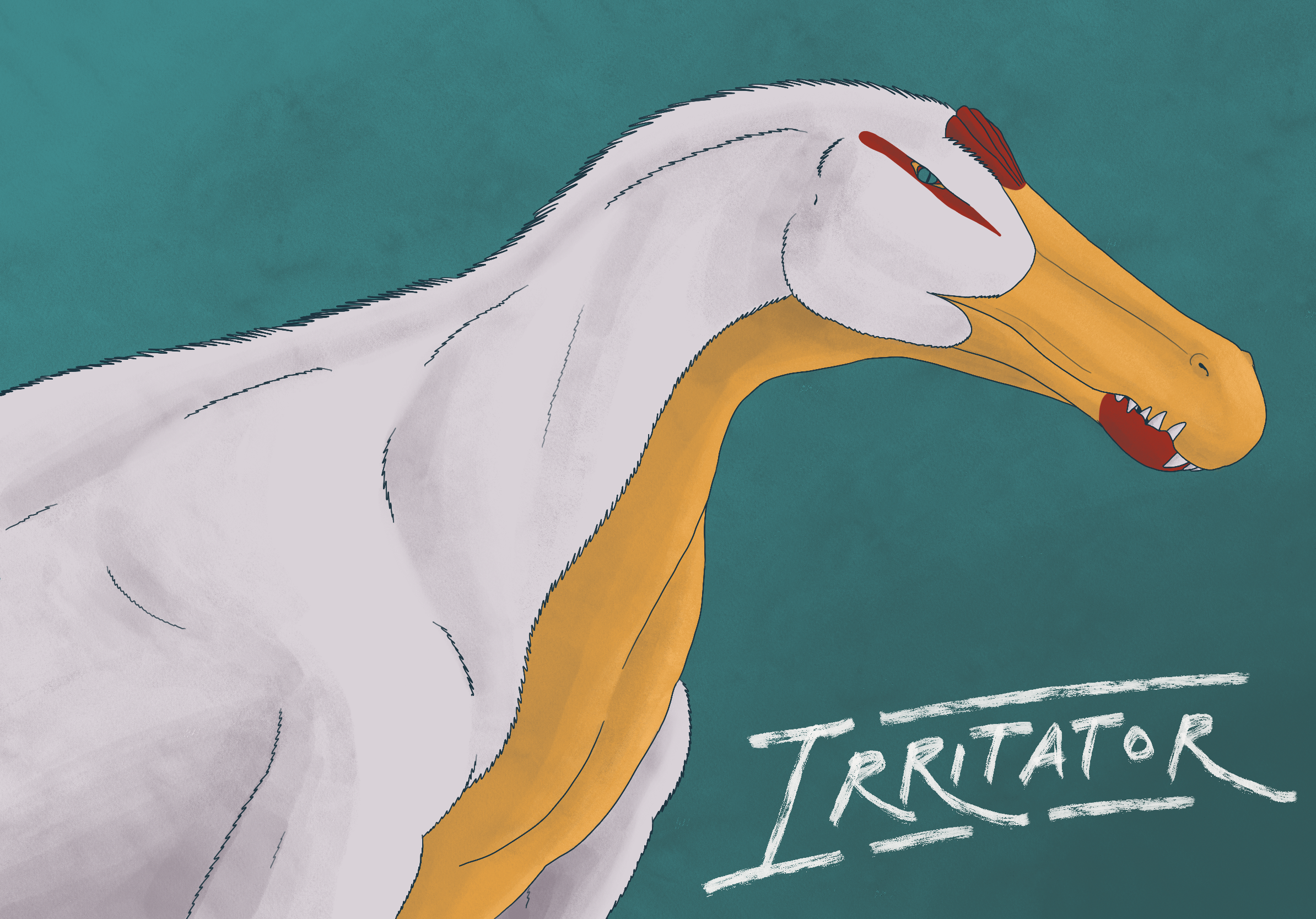

I is for Irritator

Irritator was a small spinosaur from Early Cretaceous Brazil. It weighed only around a tonne, which means I can give it some feathers without worrying about fatal overheating (the “Yutyrannus threshold” over which feathers are unlikely is 1.4 tonnes). I also gave it the half-lips that are now in vogue among paleoart depictions of spinosaurs.

Spinosaurs like Irritator were semi-aquatic, and their faces were very crocodile-shaped, with pressure-sensitive pits and a toothy rosette. Their center of mass was so far forward of their rather short hind legs that it’s possible that they couldn’t really walk very well on land, like a modern loon. Some paleoart depicts them as knuckle-walkers, but this is unlikely.

Irritator is named that because the holotype had been tampered with, causing irritation among the scientists who prepared the specimen. Here’s Irritator in seabird colors (I was going for a seagull look but with the red crest it looks a bit more like a chicken), looking vaguely irritated.

J is for Jeyawati

Trying my hand at Proceate animation! Jeyawati, meaning “grinding mouth,” was a hadrosauroid (early “duck-billed dinosaur”) from Late Cretaceous New Mexico. Hadrosaurs were one of the few groups of dinosaurs that actually chewed their food, using a diagonal grinding motion where their lower jaw moved forward and back while their upper jaw flexed in and out simultaneously (unlike mammals, they couldn’t move their jaws side to side). Chewing allows for more efficient extraction of nutrients, which was especially useful given the spread of grasses in the Cretaceous, since grass is very abundant but not very nutritious, and hadrosaurs didn’t have the intense multi-stomach system modern mammalian ruminants have.

The type species of the genus Jeyawati is called rugoculus, meaning “wrinkly eye,” because the bones around its eye have a texture that indicates an attachment point for keratinous structures.

K is for Kol

A slightly more ambitious animation today, here’s the run cycle of Kol, an alvarezsaurid (probably) from Late Cretaceous Mongolia. Kol means “foot,” and the type species, ghuva, means “beautiful” because the holotype consists of just one beautifully preserved foot. Kol’s foot was arctometatarsalian, which means the foot bones were shaped in such a way that was good for running, so here he is running. Alvarezsaurids were specialized insectivores with just one claw on each hand that they used for digging into insect nests. I based the run cycle on a video of a pheasant.

L is for Ledumahadi

Ledumahadi was a lessemsaurid sauropodomorph (early relative of the long-necked dinosaurs) from Early Jurassic South Africa. Its name means “giant thunderclap at dawn,” because it is by far the largest known animal up until then, weighing in at around 12 tonnes. Ledumahadi and other lessemsaurids look to me like someone tried to draw a sauropod without actually knowing what they were supposed to look like. Ledumahadi had digitigrade back legs and three visible claws on the front legs, while most later sauropods had plantigrade back legs and one or zero visible claws in front. Ledumahadi also lacked the columnar limbs developed by later sauropods, which means that while standing neutrally, its elbows and knees would’ve been slightly bent, as opposed to having all the bones stacked on top of each other like a column. Without columnar limbs, it appears that an animal can only reach around 12-16 tonnes, as evidenced by Ledumahadi and Shantungosaurus, the giant ornithopod.

Here is a family of Ledumahadi who woke up early and smelled rain in the air, so they are taking shelter under a tree.

M is for Mussaurus

Two sauropodomorphs in a row! Mussaurus was a medium-sized (one tonne) sauropodomorph from Late Triassic Argentina. Its name means “mouse reptile” because it was originally known only from fossils of juveniles, which were six inches long. I wanted to highlight this huge difference in size in this picture. Juvenile Mussaurus had short faces and big eyes, and walked quadrupedally, while the adults had long snouts, long necks, and were bipedal. Given the huge size difference, I think it’s unlikely that Mussaurus exhibited any kind of parental care, instead probably just burying a hundred tiny eggs in the dirt and scooting off.

N is for Notatesseraeraptor

Notatesseraeraptor was a basal theropod from Late Triassic Switzerland, described just last year. It appears to represent a transitional form between the more basal coelophysoids and the later dilophosaurids, showing a mosaic of traits found in both groups–hence its name, meaning “trait mosaic thief”. The background is based on azulejos, the traditional Portuguese mosaic tiles (which you may recognize from the board game Azul).

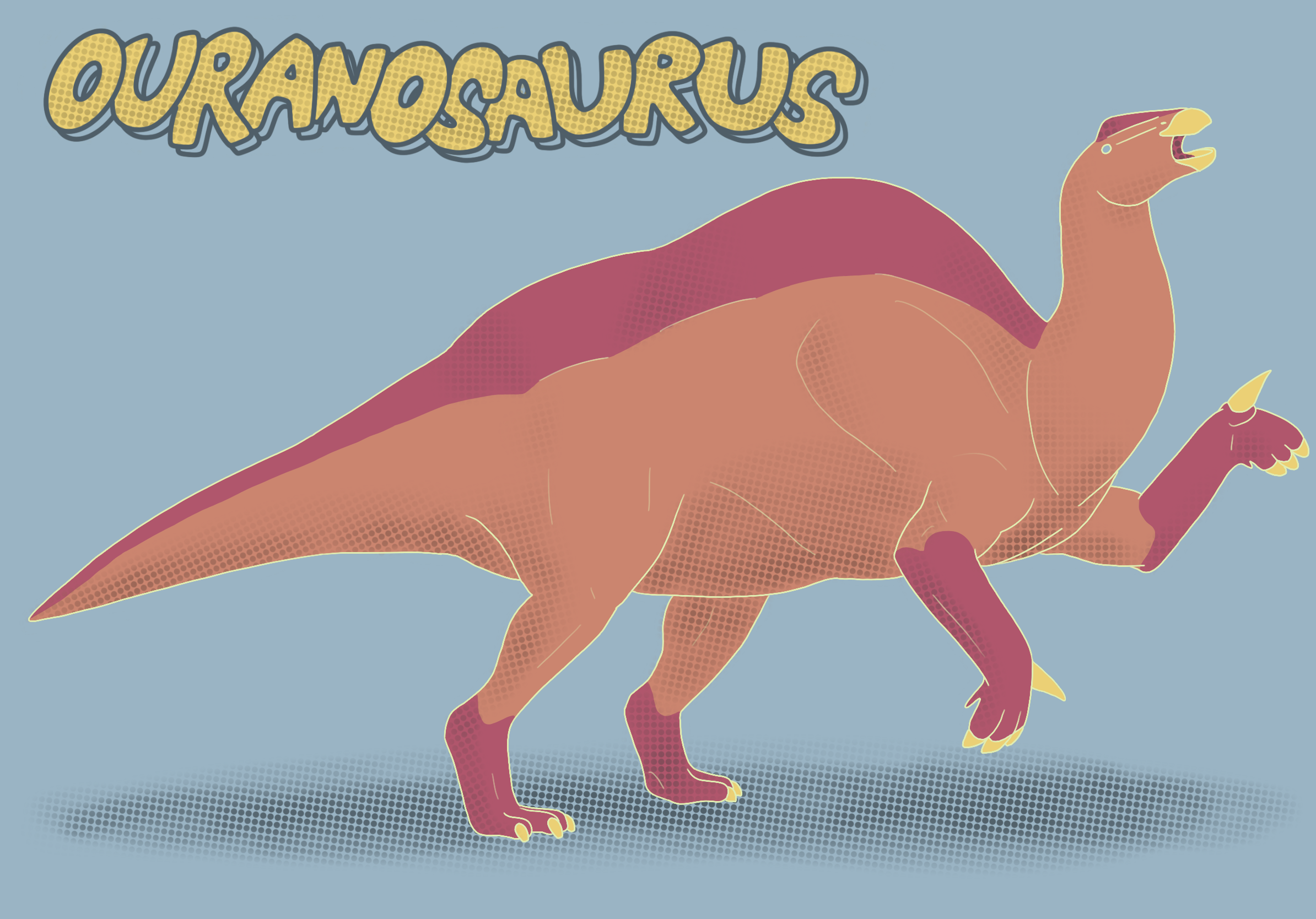

O is for Ouranosaurus

Ouranosaurus was an iguanodont from Early Cretaceous Niger. It was a 2-4 tonne beaked herbivore with tall neural spines that formed a sail or a hump, and large thumb claws for defense. Ouranosaurus means “brave reptile,” so this one is waving its claws in a threat display. The coloration is loosely based on that of a Przewalski’s horse.

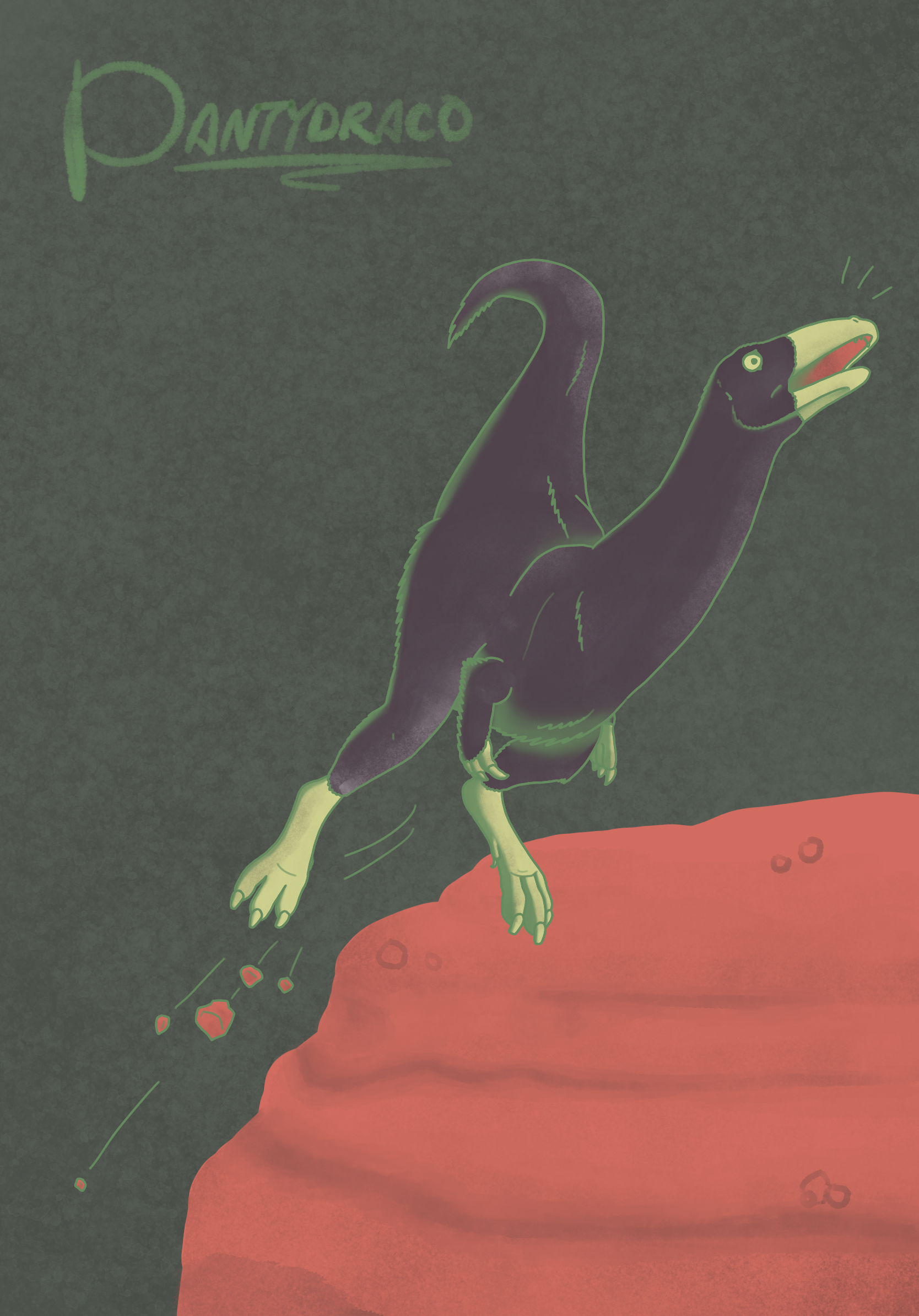

P is for Pantydraco

Pantydraco (meaning “hollow of the dragon” in Welsh–why are you laughing?) was a sauropodomorph from Late Triassic Wales. The ancestral condition of both theropods and sauropods was bipedal carnivory, so early sauropodomorphs were omnivorous before switching entirely to herbivory. The type species, caducus, means “fallen” because the holotype specimen appeared to have fallen into a fissure and died there. So, here’s the individual who is about to become the holotype, failing to watch his step.

Q is for Qantassaurus

Qantassaurus was a small ornithopod from Early Cretaceous Australia, when the continent was still connected to Antarctica. It was probably related to the slightly larger and more famous Leaellynasaura. Qantassaurus was named after the Australian airline, QANTAS (Queensland And Northern Territory Air Service) due to their help with and sponsorship of paleontological efforts in the ’90s. This picture is in the style of the QANTAS logo.

Qantassaurus was a polar dinosaur that would have experienced months-long nights and well below freezing conditions. Given its small size, it was probably very fluffy to insulate against the harsh conditions. The amount of fluff I’ve given it here is actually probably conservative.

R is for Rubeosaurus

Rubeosaurus (meaning “thornbush reptile”) was a ceratopsian from Late Cretaceous Montana. It was very closely related to the similarly spiky Styracosaurus, in the family Centrosaurinae (the other main family of ceratopsians was the Chasmosaurinae, which includes Triceratops). Those top two horns grew toward each other, which makes me wonder if in old individuals they could’ve fused at the top. This Rubeosaurus is peering out from within, well, a thornbush.

S is for Scelidosaurus

Scelidosaurus was a basal thyreophoran (armored dinosaur, the group containing plate-backed stegosaurs and tank-like ankylosaurs) from Early Jurassic England. Along with Scutellosaurus, it shows the transition between the ancestral ornithischian “lightweight bipedal runner” body plan and the derived “siege engine” body plan. The other creature depicted here is Dimorphodon, an early pterosaur. It was famously depicted in Jurassic World as a T. rex-headed hellbat, which many viewers unfamiliar with paleontology thought was made up. It does sort of look like a theropod-headed pterosaur, but it was a rather diminutive creature that hunted small prey on the ground, and definitely wasn’t capable of carrying off screaming humans clutched in its feet. (Pterosaurs had walking feet, not grabbing feet, anyway.) Here, a curious Dimorphodon startles a browsing Scelidosaurus.

Scelidosaurus means “rib of beef reptile” because Richard Owen, who described and named it in 1859, erroneously thought “scelido” meant “leg” in Greek (the prefix he was looking for is “scelodo”). The funny thing is, since then, numerous other animals have also been named after ribs of beef, such as Scelidotherium, Scelidodon, Scelidocetus, Scelidomachus, and Scelidotoma. I guess Richard Owen ended up just changing Greek, or creating a taxonomy meme, or something.

T is for Thanos

Everyone got really excited when this new dinosaur was described in 2018–it’s named after the Marvel character! I’m definitely not the first to give him chin folds and purple coloration, but I think this is the first animation out there. Thanos was a medium-sized abelisaur (the group of “mouth with legs” carnivores including Carnotaurus and Ekrixinatosaurus) from Late Cretaceous Brazil, known from a single neck vertebra. I think it’s pretty cool that paleontologists can place an animal in a pretty precise position on the tree of life based on just a vertebra!

U is for Unenlagia

Unenlagia (meaning “half-bird”) was a dromaeosaur from Late Cretaceous Argentina. It was a member of the eponymous Unenlagiinae, a group of slender, long-snouted dromaeosaurs that were common in the Southern Hemisphere, as eudromaeosaurs populated the Northern. The long snouts led paleontologists to think of the family as piscivores, maybe similar in lifestyle to modern herons. Here, Unenlagia swallows a large fish. This probably isn’t even the biggest thing it could swallow whole. You can cage a swallow, can’t you, but you can’t swallow a cage, can you?

With this drawing, I was attempting to emulate the style of the artist calling themself Small Microraptor. Turns out this is a pretty nice style!

V is for Vespersaurus

Vespersaurus (meaning “evening reptile”) was a noasaurid ceratosaur (relative of abelisaurs like Carnotaurus) from Late Cretaceous Brazil, described just last year. It was known from its distinctive trackways (fossilized footprints) long before its bones were discovered. Vespersaurus’s feet were unique: it walked on a single toe, with two reduced toes held up next to it, sort of like a primitive horse or a short-faced kangaroo. Monodactyly seems to be an adaptation for fast running in arid climates, which may have aided Vespersaurus in chasing down skittering prey, like this lizard. Noasaurids in general were a strange and diverse group of dinosaurs, which survived right up to the end of the Cretaceous period. The closely related Masiakasaurus had wicked outward-pointing teeth, while Limusaurus had a toothless beak.

W is for Wannanosaurus

Wannanosaurus was a very small basal pachycephalosaur (the head-butting dinosaurs) from Late Cretaceous China. Here is one with a fluffy integument, taking a break and not head-butting anyone. Pachycephalosaurs were one of the last major dinosaur groups to arise before the end of the Mesozoic. Their closest cousins were the ceratopsians (horned faced dinosaurs, including Triceratops).

X is for Xenoposeidon

Xenoposeidon was a (possibly) rebbachisaurid sauropod from Early Cretaceous England. Its name means “strange Poseidon,” in reference to the existing genus Sauroposeidon (“reptile Poseidon,” which makes about as much sense). Very little is known about Xenoposeidon because it’s known only from a single vertebra.

Y is for Yi

Yi (meaning “wing”) was a one-pound scansoriopterygid from Late Jurassic China, and it’s basically a real-life dragon. This dinosaur group had batlike membranous wings supported by two points: their third finger, and a non-finger “styliform” bone attached to the wrist. They also had feathers on their body and tail. There are only a few known genera of scansoriopterygid: Epidexipteryx (whose fossil preserved the four long ribbonlike tail feathers I’ve given Yi here), Scansoriopteryx, Ambopteryx, Yi, and maybe Pedopenna. Before Yi was discovered in 2015, nobody knew what these dinosaurs’ long fingers were for–some suggested they poked them into trees like an aye-aye. But the holotype of Yi preserved the wing membrane, changing the way we understood this group entirely.

It’s unclear whether scansoriopterygids were capable of powered flight, or if they just glided, but based on this new research into the evolutionary trends of gliding animals, I’d bet that they were gliders. Unlocking true powered flight would’ve presumably spurred explosive diversification, but just adapting to glide better fits with the fact that only a few types of scansoriopterygids are known, and all of them are very similar.

Update: Even newer research suggests that they were indeed just gliders, almost certainly incapable of powered flight.

Here, Yi launches off a tree to glide to another, like a flying squirrel. I don’t actually know if there’s evidence one way or another for them being nocturnal or diurnal–if you know, please tell me!

Z is for Zuul

Zuul was an ankylosaur from Late Cretaceous Montana, described in 2017 and named after the demon dog from Ghostbusters. Its species name, crurivastator, means “destroyer of shins” because of the animal’s low-slung stance and formidable tail weapon. A beautifully-preserved, nearly complete skeleton has been found and is being prepared, but as of now only the head and tail have been formally described. Did you know that ankylosaurs almost always fossilize upside-down? All that heavy armor on their backs means that if they end up in water, they flip over. Zuul was no exception.

Ankylosaur fossils are particularly cool because, since much of their bodies were covered in osteoderms that fossilize easily, we know their life appearance almost exactly. Same with placoderms like Dunkleosteus and many invertebrates like eurypterids and trilobites.

And with that, we’ve reached the end of the Alphabestiary! Hope you enjoyed my selections. I had a good time doing all these in quarantine. Maybe I’ll do another theme in a little while. Thanks for reading all the way to the end!