We’re back for more bird ecology! If you haven’t seen it yet, part 1 is located here.

Carnivory

Carnivorous birds share a lot of common traits, such as hooked beaks, fierce eyes, and sharp talons, but much of that is due to convergent evolution. Hawks, eagles, and vultures are in the same family, the Accipitriformes, while owls are in their own family, the Strigiformes; falcons are even more distantly related, and are closer to the songbirds. Since they evolved carnivory independently, it makes sense that they’d have different ways of going about it.

Foot plunging. This is probably what you think of when you imagine a bird of prey hunting: diving foot-first, talons outstretched, to snatch a mouse or songbird. Eagles, hawks (both buzzard-hawks, including the red-tailed, which specialize on mammals, and accipitrine hawks, which specialize on birds), owls, and many falcons employ this method to take down their prey. After killing it, they often go to a “plucking post” to remove the feathers, fur, bones, and other inedible parts before eating. For the most part, foot-plungers go after prey significantly smaller than themselves, since they deal the killing blow by puncturing and squeezing and since they often need to fly while carrying their prize. However, some exceptions such as harpy eagles and golden eagles go after prey equal or larger than themselves–harpy eagles can kill sloths the same weight as themselves and carry them short distances, and golden eagles are known to cause mountain goats much heavier than themselves to fall off cliffs. In the past, the giant Haast’s eagle from Pleistocene New Zealand somehow managed to take down moa birds and human children weighing many times more than themselves.

Different raptors have slightly different uses for their talons: many hawks and eagles have oversized thumb and first-finger talons that they use to dismember prey; owls have four equal talons that squeeze prey to death in a strong grip, which is then swallowed whole; falcons have small talons since they don’t specialize as much in foot-plunging; and ospreys have strongly curved talons that grip fish like a fishhook.

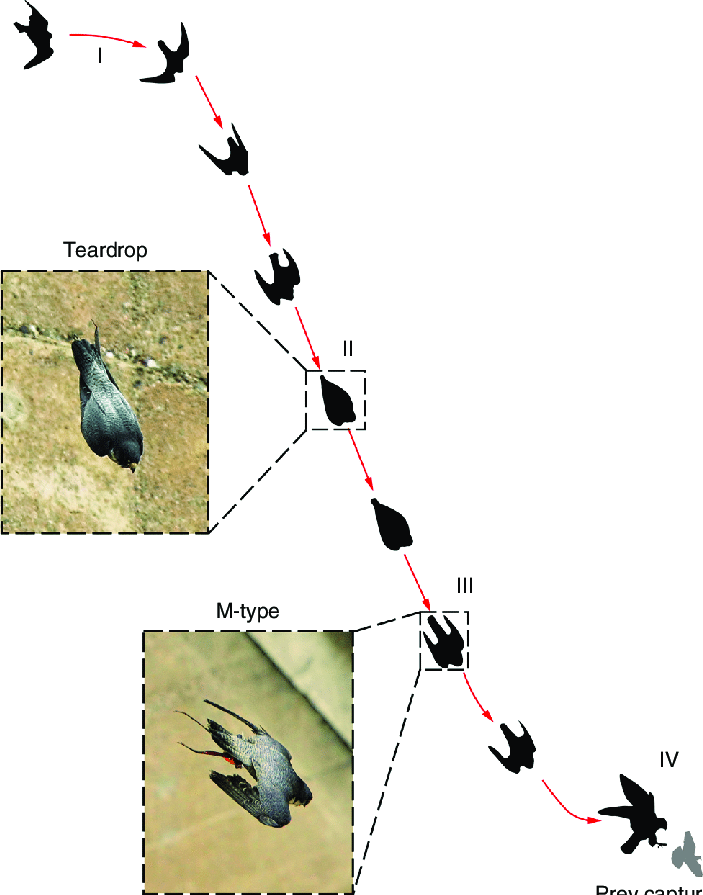

Punching. Probably one of the most specialized hunting methods, this is how peregrine falcons (and sometimes other falcons, such as the prairie falcon and merlin) manage to kill prey larger than themselves: they dive at their prey, often a bird larger than themselves, at high speeds, and punch the wing with a clenched foot, either killing it on impact or causing the bird to crash-land. So there’s actually some basis for the Falcon Punch! Sometimes, the blow is so intense that they can literally punch the victim’s head off. This is an awesome, but very dangerous lifestyle–59 to 70% of peregrines don’t survive their first year (ten months of which they’re living independently from their parents), and another 25 to 35% die each subsequent year. They have a suite of interesting adaptations to aid them in attaining high speeds safely: a convoluted nostril to reduce air pressure that might hinder breathing, viscous tears, a high visual frame rate, and extra vertebrae in the tail to allow for stronger braking muscles.

Stomping. Some birds, like the seriema and secretary bird, prefer a terrestrial mode of hunting. They have long legs with sharp claws that they use to stomp prey to death, which is especially effective on snakes and other venomous prey you’d want to keep at arm’s length. Seriemas even have a sickle claw that is held off the ground, like a raptor dinosaur, which is used to disembowel prey. However, raptor dinosaurs had relatively short legs, so it’s unclear if this feature is analogous or not.

Hammering. You didn’t think a woodpecker’s overengineered drilling apparatus was only for pecking wood, did you? Many woodpeckers are opportunists, supplementing their insect diet with meat when it’s available. And sometimes that means raiding other birds’ nests and eating the brains of their young. A nestling’s skull isn’t all that different from an egg, which woodpeckers are also adept at eating. This behavior has been observed in Gila, red-bellied, and red-headed woodpeckers, but it’s probably quite widespread across the woodpecker family. The great spotted woodpecker also uses this technique on crabs and snails.

Scavenging. Lots of birds will scavenge when they can, but three families of birds have turned this up to eleven. Vultures, which are in the same family as hawks and eagles, are actually comprised of three groups that have convergently arrived at similar specializations for scavenging. They have broad wings and are able to soar long distances with little effort in search of a meal; they often have bald heads, allowing them to stay clean when buried neck-deep in a carcass; and they have very acidic stomachs, which kill decomposer bacteria that prevent other animals from scavenging to the same degree. New World vultures, including the turkey vulture, condors, and others, have a keen sense of smell that helps them locate food, but Old World vultures and gypaetine vultures are poor smellers and rely on sight. Even among vultures, there is specialization. Some, like the cinereous vulture, will only eat the meaty parts of a carcass, disdaining organs (though they do eat putrid meat). Others will eat offal happily, and the bearded vulture almost exclusively eats bones. Condors rely on beached whales and other marine animals (though they didn’t used to). Some vultures even eat poop–in Egyptian vultures, cow poop is thought to contribute the orange pigment the birds use in their faces.

Vultures are important ecologically for safely disposing of harmful pathogens and keeping the population of terrestrial scavengers in check. Between 2000 and 2007, multiple species of vultures in India suffered enormous (up to 99 percent) losses due to the use of a veterinary drug given to cattle, which caused kidney failure in vultures. The drug was banned when it was pinpointed as the cause, but vultures are long-lived and slow-breeding, so the population is still extremely low. In their absence, the populations of wild dogs and rats have increased substantially, and zoonotic diseases transmitted by these animals have become much more common.

Herbivory

Let’s finish on a more wholesome note–herbivorous birds. As with all bird lifestyles, there’s a wide variety of ways to be an herbivore, and I’m sure I’m forgetting some. Don’t hesitate to reach out with additions or corrections!

Granivory. If you ask a child what birds eat, I’d bet they’d answer “birdseed”. Sparrows and finches, gamebirds like grouse, quail, pheasants, and partridges, doves and pigeons, and some parrots are all granivores that specialize in different types of seeds or different ways of obtaining them. Sparrows and finches with small beaks pluck small seeds out of flowers and grain crops, while finches with bulkier bills go for larger seeds like sunflower and safflower. Crossbills, which have upper and lower mandibles that cross over each other, use their weird beaks to pry the seeds out of pinecones.

Gamebirds specialize in pecking, picking up seeds that have already fallen off the plant (though they get a lot of their nutrition from insects as well). Small parrots like the budgerigar (“budgie”) eat grass seeds and crop grains, while large parrots can crack tough nuts, including the aluminum-like macadamia. Some granivorous birds are considered crop pests, while others prefer the seeds of weeds and are agricultural benefactors.

Granivory is also known as “seed predation” since the seed is destroyed and unable to germinate. Granivores are at war with plants, while frugivores (fruit eaters) are doing the plants’ bidding. I would think frugivory would’ve won out by now?

Nectarivory. Hummingbirds are the obvious practitioners of this lifestyle, but other birds, such as sunbirds, honeyeaters, honeycreepers, and even a type of parrot (lories and lorikeets) convergently do as well. Nectivorous birds often have long, downcurved bills and long, brush-tipped tongues that can soak up liquid. Hummingbirds and honeycreepers are endemic to the Americas, while sunbirds live in Africa and honeyeaters and loriees in Oceania. Plants that rely on nectarivorous birds for pollination often produce reddish, tubular flowers; however, hummingbirds are the only ones that regularly hover while feeding, so in the Old World these plants have to worry about providing an appropriate landing pad for the birds. Hummingbirds are known to visit the same flowers in the same order in a routine, known as “traplining”, timed to coincide with the nectar replenishment rate.

Dabbling and diving. These are the two ways ducks and coots obtain food, and most ducks can be assigned to one group or the other, though some diving ducks also dabble. Dabbling involves upending oneself, submerging the head and neck, to access shallow aquatic plants, algae, and invertebrates. Diving involves going fully underwater, often to dig up roots or inverts from the muddy bottom. Ducks that dive tend to have their feet placed further back along the body, which makes them less adept at walking.

Frugivory. Fruit is plants’ attempt at evolving candy–if a plant could grow a Snickers bar with seeds inside, it would–so it’s no surprise that many animals love to eat it. Many fruit-bearing plants have a preferred eater whose digestive system and locomotory habits are ideal for that plant’s seed dispersal, and the color, shape, size, flavor, and fragrance of the fruit reflects that. Hot peppers were until recently bird-dispersed plants–birds aren’t affected by the spicy capsaicin. Other fruits are toxic to the wrong animals–think of those attractive red berries on bushes at school you were told not to eat. Most bird-dispersed fruits are colorful, small, and scentless, with small seeds, while mammal-dispersed fruits are large, duller in coloration, fragrant, and contain large seeds or pits.

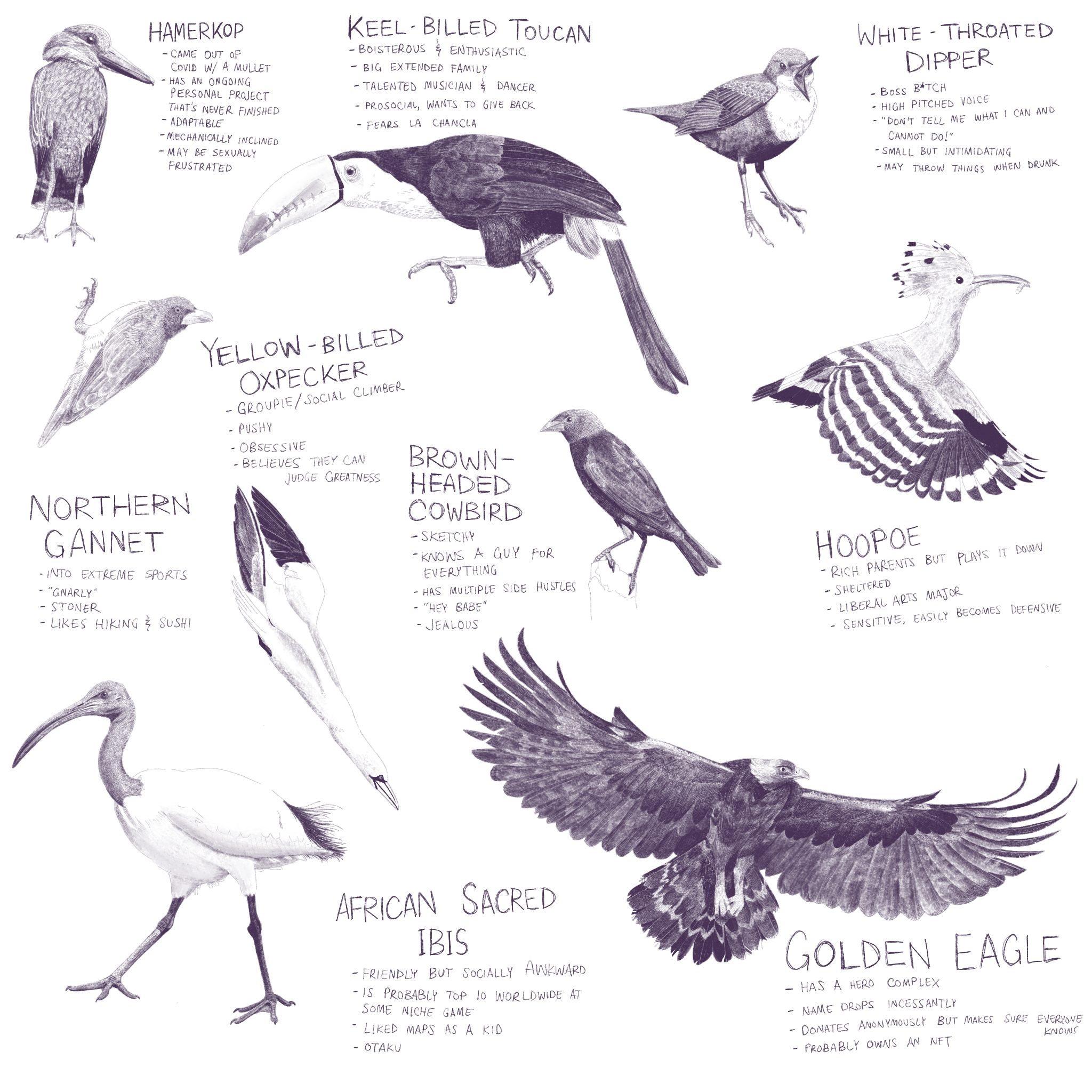

Many birds will eat fruit when given the chance, including many songbirds, groundbirds, and woodpeckers, but some birds are fruit specialists, such as waxwings, bananaquits (also known as “sugar birds” since they’re attracted to bowls of granulated sugar), hornbills, toucans, cassowaries, orioles, robins, and parrots. Two species of bird are hyper-specialized and only eat a single species of plant: the mistletoebird eats only mistletoe berries, and the Pesquet’s parrot eats strangler figs.

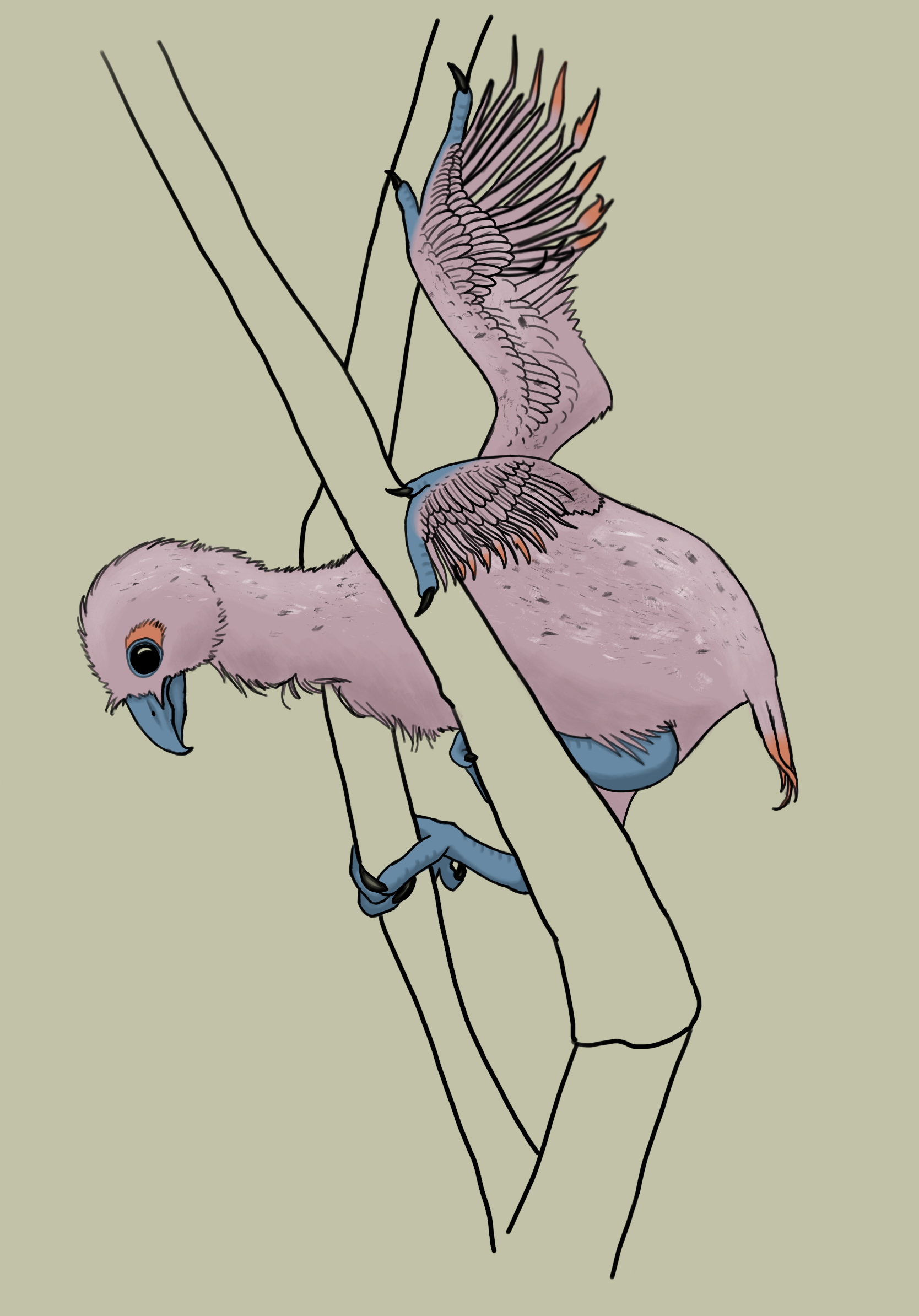

Both of these plants are epiphytes, meaning they grow on other trees, so they’re dependent on birds to deposit seeds in neighboring trees. Mistletoe seeds are surrounded by a super-sticky substance, which means the bird’s poop is also sticky, which means they have to wipe their little butts on branches to dislodge it, depositing the seed just where it wants to be. Mistletoe birds also have short, simple digestive systems that allow seeds to pass through quickly and unharmed, and even a special valve that causes the mistletoe seeds to bypass the stomach altogether, while tougher foods don’t do this. What the heck does the bird get out of this arrangement? Answers on a postcard…

Folivory. This is the rarest habit in birds, due to the poor nutritional value of leaves compared to fruit or animal protein. Leaves are also tough, requiring a large, complex gut with special bacteria to break them down, which is heavy, reducing flight ability. While some birds, like starlings and griffon vultures, have been seen eating pine needles for an unknown reason, the only birds that get most of their calories from leaves are the hoatzin, of South America, and the kakapo, of New Zealand. The hoatzin (also known as the “reptile bird” since its chicks retain little clawed fingers) is a poor flyer, and the kakapo (also known as the “owl parrot” for its owl-like facial disc that aids hearing) is completely flightless, both preferring to clamber around in trees using their feet and beaks. They also both smell funky due to the fermentation taking place inside–the hoatzin apparently smells like manure, while the kakapo smells “musty-sweet” (new bucket list item: smell both of these birds).

Grazing. No bird gets a majority of its calories by grazing, but geese, swans, and cranes spend a lot of time doing it anyway, and are sometimes considered pests due to the damage they cause to lawns. They don’t have the fermenting gut that mammalian herbivores, hoatzins, and kakapos do, so they’re highly inefficient at digesting grass, but at least they don’t have to deal with wearing their teeth down as mammals do. Birds store small, hard rocks in their gizzards, which chew food and negate the need for complex teeth. Like many things birds do, it’s a much better system.