The activity of birding comes with a lot of jargon, such as “GIS” (General Impression and Shape, pronounced “jizz”), “pishing” (making noises at birds to get them to react so you can get better photos–it’s not recommended), “vagrant” (a bird found outside its usual range, often due to storms), and more. A lot of terms have to do with the way birds live and behave, a big part of which is the way they eat. I thought it would be interesting to put together a list of terms both for the purpose of learning new words and for highlighting the huge variety of things birds do to obtain and process their food.

Insectivory

There are nearly 10,700 species of bird, and over half (>6000 species) are insectivores. The insectivorous birds of the world collectively weigh around 3 million tonnes, but consume 400 to 500 million tonnes of insects every year, and thus have a huge impact on pest population control and ecological balance. There are quite a few methods birds employ to find and eat insects, including:

Gleaning. This just means plucking insects off some surface, and is the most common technique. However, it can be subdivided into numerous niches, and there are lots of different ways to go about it. For example, turkeys walk around in bushes and grass, looking for ticks; bushtits peer under leaves to find aphids and caterpillars; robins scratch at the leaf litter with both feet to expose grubs and worms; nuthatches walk vertically on tree trunks looking for bugs in the crevices of the bark; grackles follow farmers’ plows to glean exposed dirt-dwelling insects; Brewer’s blackbirds frequent parking lots to pick dead insects off the fronts of cars; and oxpeckers pluck ectoparasites like ticks and fleas from large mammals, as well as maggots from any wounds their hosts have. Birds that glean commonly have very small, tweezer-like beaks, and operate during the day, since they rely on sight to locate their prey. They are also commonly social, foraging in mixed-species flocks for safety–since you’re focused on what’s right in front of you when gleaning, you’re vulnerable to predators, and want more eyes around to increase the chance someone will see one and raise the alarm.

Hawking. The opposite technique to gleaning, hawking means chasing down flying insects on the wing and nabbing them with the beak. Counterintuitively, hawks do not hawk–even if a hawk were to eat an insect, a hawk’s weapon is its talons rather than its beak. Most birds that do this, such as flycatchers, tyrant flycatchers such as phoebes, bee-eaters, and others, employ a technique known as sally-striking. They perch on a branch or pole and wait for an insect to come into range, and then “sally” out and grab it. Some return to the same perch over and over, like the black phoebe, while most move from one perch to another while hunting. This style of insectivory is extremely energy-intensive, so birds must be good at hawking insects for it to be worth the calories expended, and many supplement hawking with gleaning. Other birds, which are more adapted for an aerial lifestyle, don’t require a perch to catch insects, such as swallows, swifts, and nightjars. These wide-mouthed birds can stay airborne for literally months at a time, eating insects, skimming over water to drink, and even sleeping on the wing.

Scaling, sloughing, and excavating. Sometimes considered a subset of gleaning, this is a behavior in which birds pry up bark or make holes in wood to get at wood-burrowing insects like termites and beetle larvae. This is most commonly and thoroughly done by woodpeckers, but nuthatches and others also remove pieces of bark.

Shellfish eating

As insects are abundant on the land, so too are marine invertebrates a great source of calories from the water. Many birds have come up with various adaptations for exploiting this food source, which have resulted in very differently-shaped birds!

Probing. The most common strategy for nabbing inverts in terms of number of species that do it, this is when birds stick their bills in the mud in search of worms, isopods, larvae, crustaceans, and mollusks. Some probers only probe the surface, or specialize on picking off prey that’s temporarily come up for air, and thus have short bills, such as sandpipers and plovers; other probers go extremely deep, like the long-billed curlew. In this way, the shorebirds can niche partition and reduce competition with one another. Many probing birds have special hinged bills that can open just at the end, like a T. rex grabbing toy, and pressure sensitive organs in the bill that allow them to sense their prey without seeing or smelling it. Some birds probe terrestrially, like the American woodcock and the kiwi, which hunt worms on the forest floor, but they are much less common than probing waterbirds. Apparently the job is less lucrative away from the sea.

Once when I was at the beach, I saw a dapper-looking western gull probing for sand crabs. It would walk around a bit, peering at the ground, and then suddenly strike and come up with a crab. I assume it was looking for bubbles or sand movement that indicated a crab’s presence. Later that same day, I saw a juvenile gull (you can tell because they have mottled brown feathers instead of the clean white and gray) attempting the same technique, but having much less success. You could just tell from the bird’s body language that it was unsure of itself. Probing, at least for generalists like gulls, takes practice!

Sweeping. While invertebrates are often found in mud, they are also often found in the water, and the strategy for exploiting that resource with the lowest evolutionary overhead is sweeping. A bird submerges the tip of its bill, held slightly ajar, and slowly sweeps it back and forth, and when something touches the inside of the bill, the bird snaps it up. The best sweeping practitioners are spoonbills, which employ this technique exclusively, but avocets and some ducks are known to do this as well.

Straining. Unlike all the feeding methods up to this point, straining is the exclusive domain of one group, the flamingos. Filter-feeding is very common among marine animals and extremely rare among terrestrial animals, the only other example being the pterosaur (flying reptile) Pterod’austro. Flamingos’ beaks are essentially upside-down whale faces, adapted for scooping up water with the neck lowered and pumping it through a mesh formed by hairs on the bill and bristles on the tongue.

Gaping and dashing. These are the methods birds use for consuming large, hard-shelled prey, which are too big or too tough to swallow whole. Gaping birds like oystercatchers use their bill as a prybar to open shells, sticking in the thin tip and then opening the mouth. Dashing is the practice of carrying shelled prey to a great height and then dropping it on a hard surface, which is apocryphally how the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus died (an eagle dropped a turtle on his head). I’ll also include in this section the practice of consuming snails by snipping the meat out of the shell with a sharp beak, like the snail kite, a small hawk that feeds mainly on snails, and the openbill storks, birds with a huge pincer for a bill, which are masters of extracting snail meat without breaking the shell. However, snail-snipping doesn’t have a catchy birder name, as far as I know. Another interesting behavior openbills use to consume mollusks is piling up mussels in the hot sun and waiting for them to bake in their own shells, at which point they release their grip on the shell and are more easily opened. Yummy!

Piscivory

Sticking with the waterbirds for now, let’s look at the myriad ways birds catch fish.

Plunge diving. Probably the most dramatic form of fishing, and one that birds are uniquely good at, plunge diving involves falling from a height into water, using momentum to carry the bird deeper than it would otherwise be able to swim. (Birds, being naturally very buoyant due to their system of internal air sacs, can’t dive unless they have special adaptations–more on that in a minute.) Birds are the only animals that are able to do this–pterosaurs’ skulls were too lightly built to survive the plunge, and bats generally avoid going into water if they can–and some birds hit the water at speeds of up to 72 kilometers per hour (45 mph)! That’s the speed you would attain by jumping off a 20-meter high dive (the tallest Olympic diving platform is only 10 meters high). Some examples of birds who plunge dive are the kingfishers, gannets, and boobies, but pelicans also sometimes join in the fun, albeit at lower speeds. To survive the plunge, these birds have a suite of adaptations, such as strengthened necks, shock-absorbing air sacs in the chest area, and dense, highly waterproof feathers so they can emerge from the water and immediately take off.

Pursuing. If a bird wants to go deeper or stay submerged longer, they face some evolutionary trade-offs. Penguins, auks (including puffins), and cormorants have dense bones compared to other birds, and dense, overlapping feathers to keep out the water. Cormorants actually fail at this on deeper dives, and since most cormorants are flighted birds, they need to allow their wings to dry after a dive before taking off again. Penguins are mostly wing-propelled swimmers and use their feet to steer, cormorants are the opposite, and auks somewhere in between. The deepest-diving penguin, the emperor penguin, has been recorded foraging at depths of 550 meters (1800 feet); auks can reach 150m and cormorants, 80. The deepest a human scuba diver has gone is a depth of 332.35 meters. It took him only twelve minutes to descend, but fifteen hours to resurface, in order to avoid the bends. This is when nitrogen from the in your lungs dissolves into your blood due to the high pressure, and then boils into gaseous form when the pressure is alleviated, like the fizz when you depressurize a Coke bottle. Resurfacing slowly allows your body to reabsorb the nitrogen before it can boil. Diving mammals avoid this problem by actually breathing out before diving, fueling their underwater motions with the oxygen stored in the blood and muscles. Diving birds do take a breath before diving, and thus must ascend more slowly than they dive; however, they can resurface a lot faster than humans. How they do this is unknown, but it’s postulated that they’re able to resorb nitrogen from the blood quicker using their system of air sacs, which dramatically increase the surface area of blood in contact with air.

Famously, the flightless great auk, a bird very similar to penguins, is extinct, but its smaller, flighted cousins, the murres, guillemots, and auklets, are still numerous. The largest, the one-kilogram thick-billed murre, is the poorest flyer in the world. Its energy cost to body weight ratio when flying is the highest of any animal. Cormorants are not much better, requiring frantic flapping to sustain flight, due to the conflicting requirements of being a good diver and swimmer (dense bones and short wings) and a good flyer (light bones and long wings).

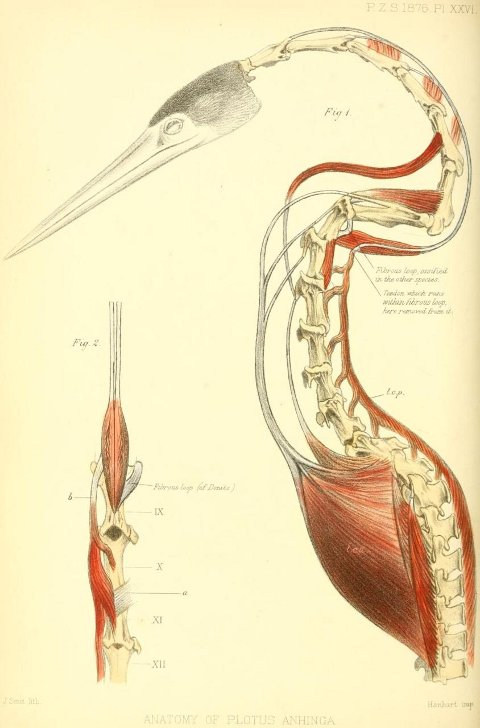

Spearing. This is one way ancient humans caught fish before the invention of string, so it’s not surprising that birds have figured out how to do it too. Herons, shoebills and hamerkops, and some tropical storks practice this method, wading carefully and watching for fish to go by before unleashing a super-fast strike. In these birds, the S-curve common to all theropod necks is exaggerated into the equivalent of a spear thrower: the kink in the middle of the neck provides leverage for throwing the head forward.

The black heron is notable for also employing a very weird-looking hunting strategy: becoming an umbrella. Casting a large shadow prevents fish from being scared off by the shadow of the striking head.

For some reason, the likeness between a human-made spear thrower and a heron’s neck shape is often used as an argument for creationism. I’m not really sure why they think one follows the other. It seems like an odd choice for a mascot given how many other potential things one could point at as being well-designed in nature (one that comes to mind is the humeral plexus, a heat exchanger in the legs of animals that live in the cold). But if we’re resorting to one-off examples as evidence, I’d propose the recurrent laryngeal nerve as the evolution-side mascot.

Skimming. This is another thing that only birds can do, and very few do–just the skimmers, of course. These birds have a lower jaw that’s much longer and more robust than the upper, which they trail in the water while flying. When prey, usually small fish, ends up between the jaws, the skimmer snaps its trap shut. Skimming seems to be a life of toil: skimmers have to expend 20% more energy to fly while skimming due to the drag on their bills, they have to have very strong neck and jaw muscles to counteract the forces exerted by the water (which I’m sure is quite tiring), and they often abrade or break their bill tips on submerged rocks or sand bars. Many pterosaurs have been suggested to have been skimmers in the past, but it’s highly unlikely due to their light head and neck construction and their size, which would increase the proportional energy costs.

Snatching. Somewhat similar to plunge-diving but feet first, this technique is used by ospreys and sea eagles, as well as the greater bulldog bat. To snatch fish with the feet, these animals have sharp, conical talons and strong legs, and eyes that are good at reducing glare off the surface of the water (in the case of the birds. The greater bulldog bat uses special echolocation that can detect ripples). The osprey also has zygodactyl feet, or two toes that face forward and two that face backward, similar to parrots, for better gripping of slippery prey.

Lunge feeding. This is when an animal with a huge mouth engulfs a bunch of water, then drains the water and retains whatever prey was in it. Today, the only examples of lunge feeders are baleen whales and pelicans, and the former is much better at it than the latter. While whales have a powerful tongue to force the water out and baleen to keep the prey in, pelicans simply angle their heads upward and open their bills a fraction, letting the water dribble out, which can take up to a minute and fails to capture very small prey. Sometimes, gulls will harass pelicans who are draining their pouches, pecking them until the gull can steal whatever was in the pelican’s mouth.

In the fossil record, a couple of other groups have tried their hand at lunge feeding: the little marine reptile Hupehsuchus and the “pancake crocs” Laganosuchus and Stomatosuchus. These animals had lightly built, probably flexible lower jaws, strong hyoid (tongue) bones, and reduced or no teeth, and Hupehsuchus may have had a baleen-like structure on the roof of its mouth.

That’s enough for now–next time we’ll cover carnivory, scavenging, and herbivory! Stay tuned.

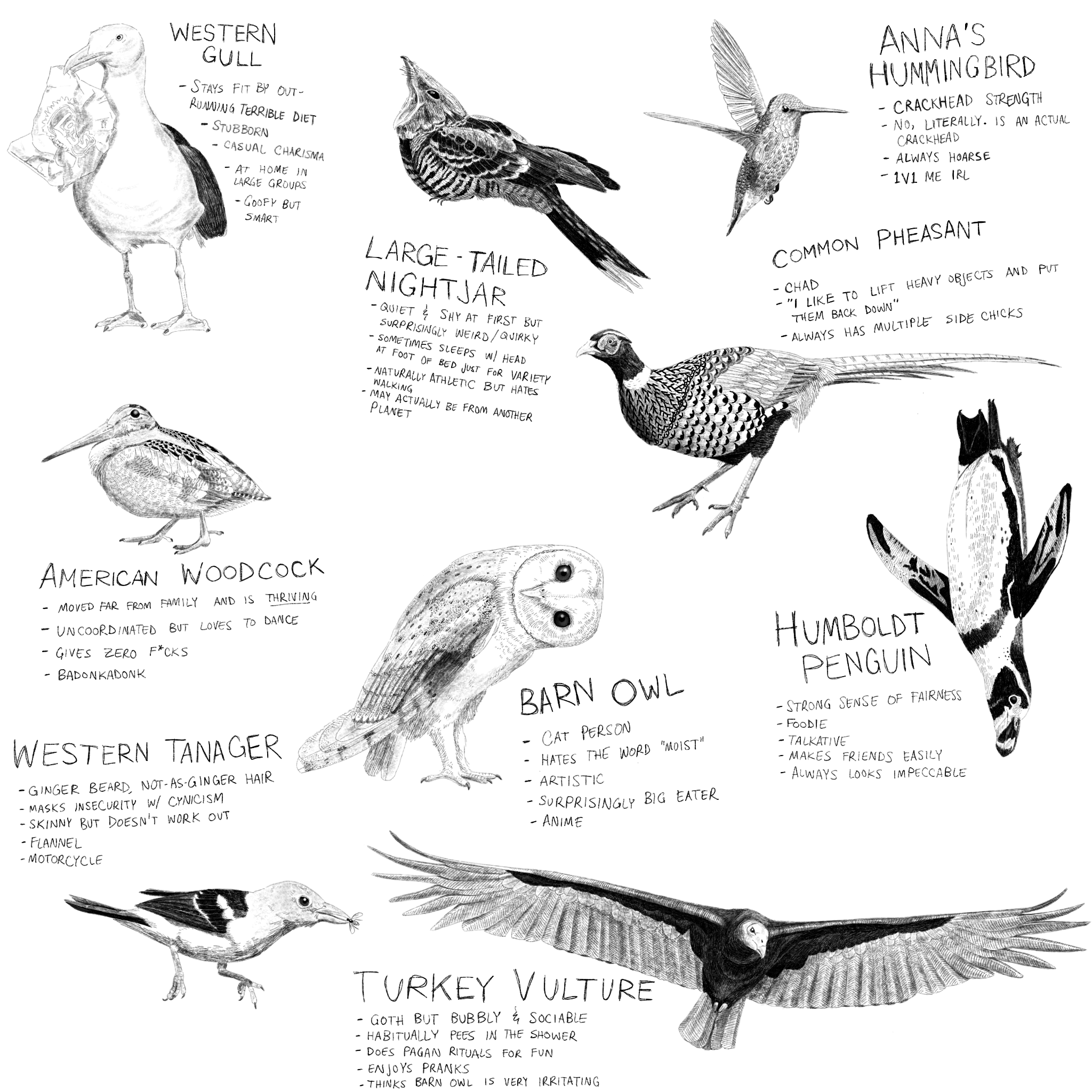

The page image is part 3 in my series of “bird horoscopes”, which the r/birding community on Reddit enjoyed. Maybe I’ll make some merch someday.

Image credits

Flamingo Openbill Gannet Anhinga neck Black heron Osprey Hupehsuchus