When I first learned about convergent evolution in school, this is the example the textbook gave: dolphins and penguins.

Dolphins and penguins have both adapted to an aquatic lifestyle by developing streamlined, torpedo-shaped bodies. Sure, that’s nominally true–but it obfuscates the real and amazing power of convergence. It sounds like it was written by someone who understood the concept at the exact level they were trying to teach–high school–and no deeper. So, here are some much better examples of convergent evolution!

1. Metriorhynchids and Mosasaurs

This is my favorite example even though neither group is very familiar to the public. Metriorhynchids are a group of crocodyliformes that adapted to a fully-aquatic lifestyle. Mosasaurs are a group of varanoid lizards that also adapted to a fully-aquatic lifestyle. Imagine a group of something that looks like a modern croc, going into the ocean and deciding to be basically killer whales before it was cool. Imagine a group of something that looks like a Komodo dragon being like, we should do that too. This is kind of what happened. Let’s get to the pictures:

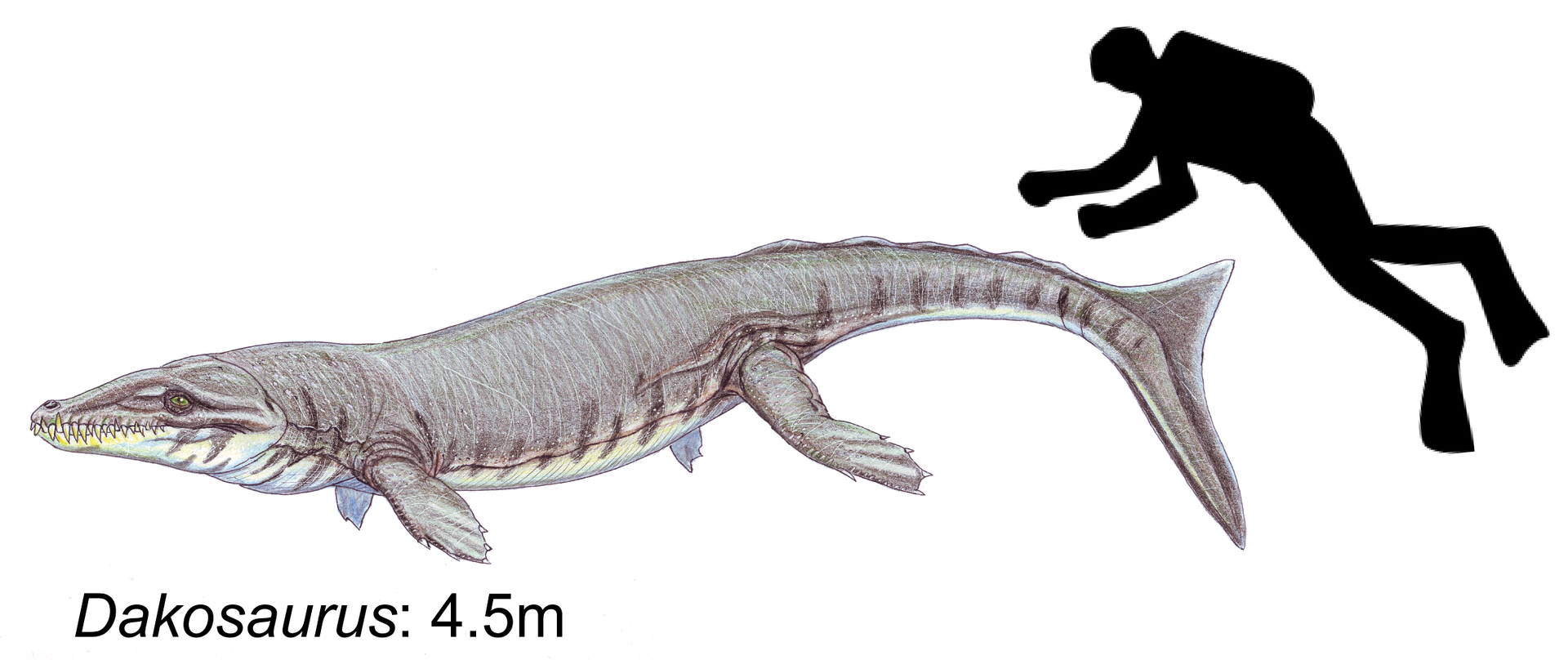

Dakosaurus - a metriorhynchid crocodyliform from Late Jurassic Germany (157-137 mya). Closely related to modern crocodiles.

Dakosaurus - a metriorhynchid crocodyliform from Late Jurassic Germany (157-137 mya). Closely related to modern crocodiles.

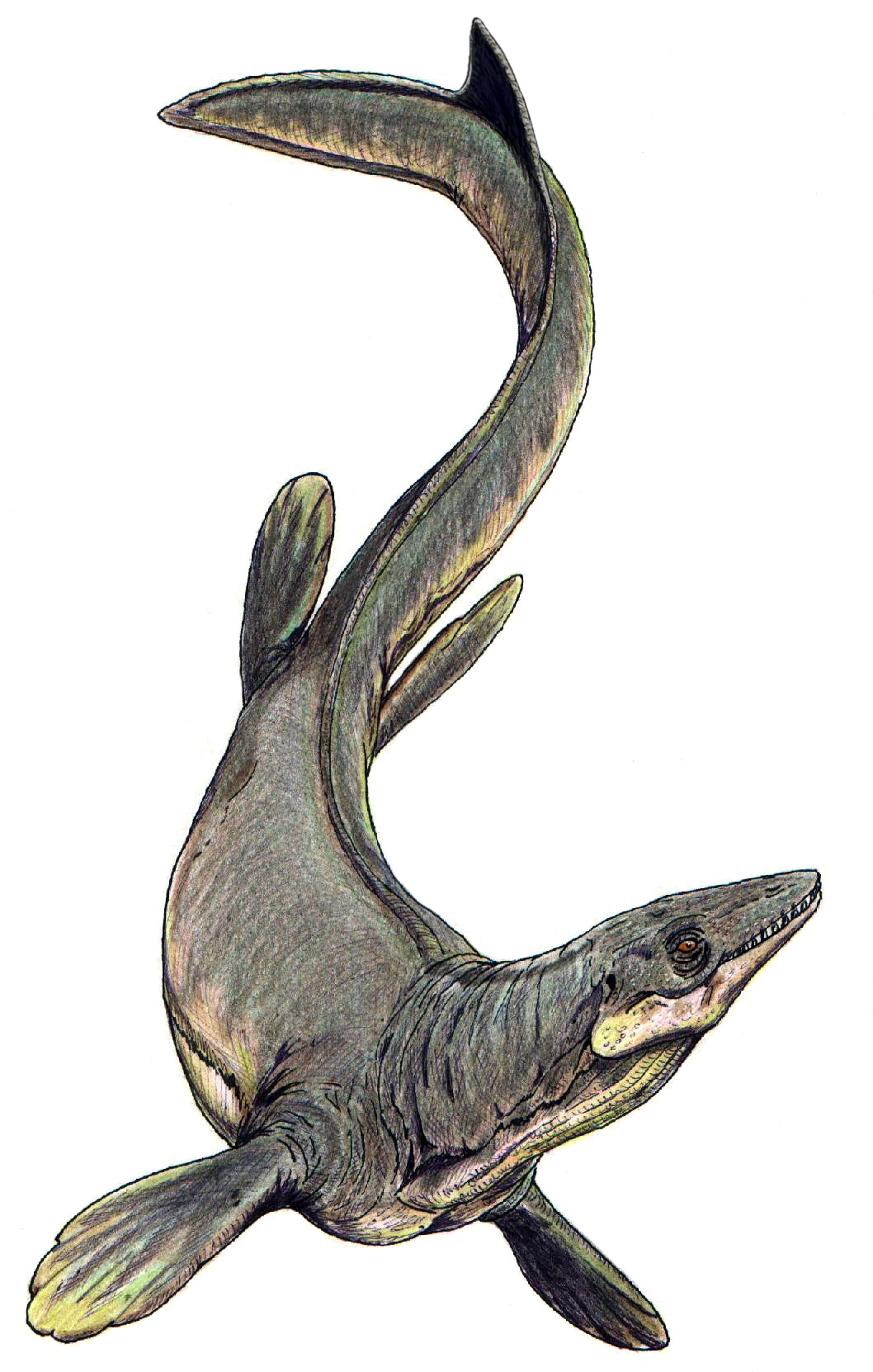

Plioplatecarpus, a mosasaur from North America and Europe in the Late Cretaceous (73-68 mya). Closely related to modern Komodo dragons.

Plioplatecarpus, a mosasaur from North America and Europe in the Late Cretaceous (73-68 mya). Closely related to modern Komodo dragons.

If you’re not looking carefully, you could be forgiven for thinking these two were the same species, even though they’re separated by millions of years of evolution (Dakosaurus is much more closely related to birds than it is to Plioplatecarpus), and also millions of years (Dakosaurus is nearly as ancient to Plioplatecarpus as Tyrannosaurus is to us).

If they’re not close to each other in genetics or in time, then why do they look so similar? Similar selective pressures, caused by similar environments. This body plan–flipper limbs, streamlined shape, fluked tail–is really good at swimming. In an environment where good swimmers survive and reproduce and pass on their good-swimmy genes while bad swimmers don’t, over millions of years you end up with something that’s very good at swimming. Both crocodylians and varanoids looked at the same problem–how do we become better at swimming?–and came up with the same solution independently. That’s convergent evolution.

Note: Metriorhynchids and mosasaurs both have hypocercal tails–tail fins where the top lobe is smaller and the bottom lobe is larger. Modern sharks, certain placoderms, and some ray-finned fish such as sturgeon have heterocercal tails, where the top lobe is larger. Ichthyosaurs and most bony fish have homocercal tails, with roughly equal lobes.

2. Mongooses and Mustelids

Now let’s move to an example that’s closer to home. Here is a mongoose and a ferret (I won’t tell you which is which):

If I didn’t know better, I’d guess that these two animals are more closely related to each other than either is to a cat or a dog; but mongooses are actually feliformes, while ferrets (and other mustelids) are caniformes. One day, a cat and a dog both said, “Let’s become tubular,” and then this happened. Jokes aside, the tubular body shape is good for a fossorial (digging / burrowing) lifestyle–the shorter your legs are in comparison to your body, the smaller your burrows have to be, and the less work you have to waste in digging. Here’s a social experiment you can do to annoy your roommates–ask a friend whether they think mongooses are related most closely to dogs, cats, or rodents. Repeat with ferrets.

Further reading: Look up the fossa, a mongoose that thought becoming tubular was a mistake and decided to start being a cat again.

3. Canids and Thylacines

The thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the marsupial wolf, is an extinct marsupial from Tasmania (the little triangular island off the coast of Australia). It’s one of many examples of convergent evolution among marsupials and placental mammals (other examples include Thylacoleo, aka the marsupial lion; the quokka, aka the marsupial pika*; and the Tasmanian devil, aka the marsupial wolverine*). All of these marsupial whatevers are more closely related to one another than they are to their placental counterpart. But they sure look similar! Here are some thylacines in a zoo, sometime before they went completely extinct in 1931:

Looks an awful lot more like a wolf than a kangaroo, don’t you think? When convergence is at work, appearances can be misleading!

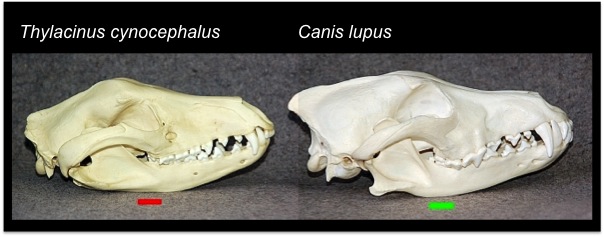

Above: skulls of a thylacine and a wolf. It’s a common test for paleontology and evolutionary biology college students to be handed one of these and asked which it is. If that’s not a testament to the power of convergent evolution, I don’t know what is. (Hint: thylacines have 8 small teeth between the big canines in the top jaw, while wolves have 6. Wolves also have a special giant molar on the bottom jaw that in thylacines is normal-sized.)

Remember that episode of Seinfeld where Elaine starts hanging out with a new group of friends that uncannily parallels her other group of friends? George tries to join that group, and Elaine says, “Sorry, we’ve already got a George.” In this metaphor, the new group of friends are the placentals and the old group is the marsupials, and “the George” of each group is the thylacine and the wolf. Basically, Elaine has certain niches that her friends can fill–the George, the Jerry, and the Kramer–and two groups of people independently filled those niches. If that makes any sense.

*nicknames not in widespread usage; so called by me (and now by you)

4. The Seven Saber Teeth

Now for something slightly different–let’s look at a single trait over time instead of a side-by-side comparison of two animals (by the way, convergent evolution happens in non-vertebrate organisms too, I’m just biased and like vertebrates best). Something we synapsids (mammals and all animals more closely related to mammals than to reptiles) are particularly good at is heterodont dentition, or the specialization of certain teeth for certain tasks. Most mammals have a variety of tooth shapes–molars, incisors, canines–while this is rare among reptiles (but does exist–see notosuchians and heterodontosaurs). One very popular and very charismatic style of dentition is the extremely elongated canines known colloquially as saber teeth.

Saber teeth have evolved no less than seven times independently among mammals and stem-mammals throughout history. Here are the groups:

- Gorgonopsids (a type of stem-mammal) in the Permian, about 270 million years ago

- Deltatheroida (a type of metatherian (stem-marsupial)) in the Cretaceous, about 100 million years ago

- Sparassodonta (another type of metatherian) in the Paleocene, about 66 million years ago

- Creodonta (a type of mammal related to carnivorans) in the Eocene, about 56 million years ago

- Nimravidae (a type of feliform but not a true cat) in the Oligocene, about 33 million years ago

- Barbourofelidae (another type of feliform) in the Miocene, about 14 million years ago

- Felidae (true cats) in the Pleistocene, about 2.5 million years ago

Gorgonops, a gorgonopsid therapsid (stem-mammal), Russia, 254 million years ago. Saber teeth before they were cool (and before pinnae (external ear-flaps) were a thing). We don’t know if these guys had fur or scales. I find that most art depicts them either as completely reptilian, with scales and osteoderms, or completely mammalian, with fur and a carnivoran-like nose. I think it’s most likely that they actually fell somewhere in between. Another interesting thing to note is that of all the saber-toothed synapsids on this list, gorgonopsids were the only ones who were able to replace their saber teeth if they fell out.

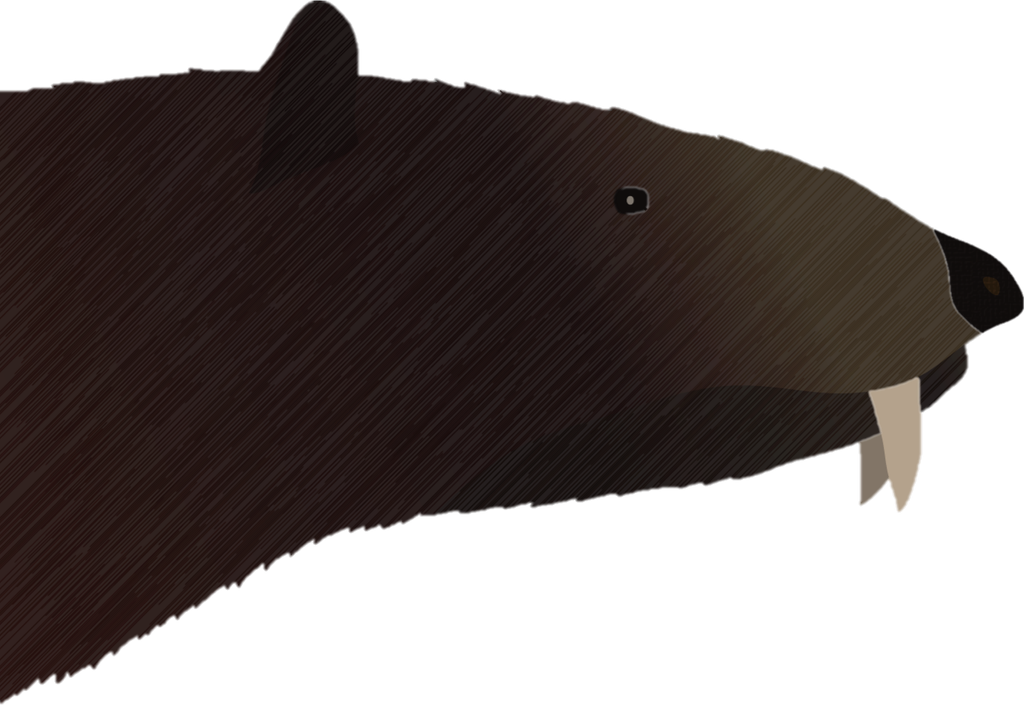

Lotheridium, a deltatheroidan metatherian (stem-marsupial), China, 100 million years ago. Saber-toothed wombat…? This is the smallest saber-toothed animal on our list, at around three feet long (the rest are close to lion-sized).

Thylacosmilus, a sparassodontan metatherian (stem-marsupial), South America, 9 million years ago*. See the weird bulge in its nose / forehead? The saber teeth actually extend all the way up through there and end behind the eyes! That, along with the crazy chin to protect the teeth, is some extreme dedication to specialized saber-toothing. The whole face is built around it! Although Thylacosmilus and Lotheridium couldn’t replace their sabers, they did have open-rooted teeth that would’ve continuously gotten longer throughout their life, like rodents.

Machaeroides, a creodont mammal (related to cats, dogs, and pangolins, but not a member of any of those), Wyoming, 56 million years ago.

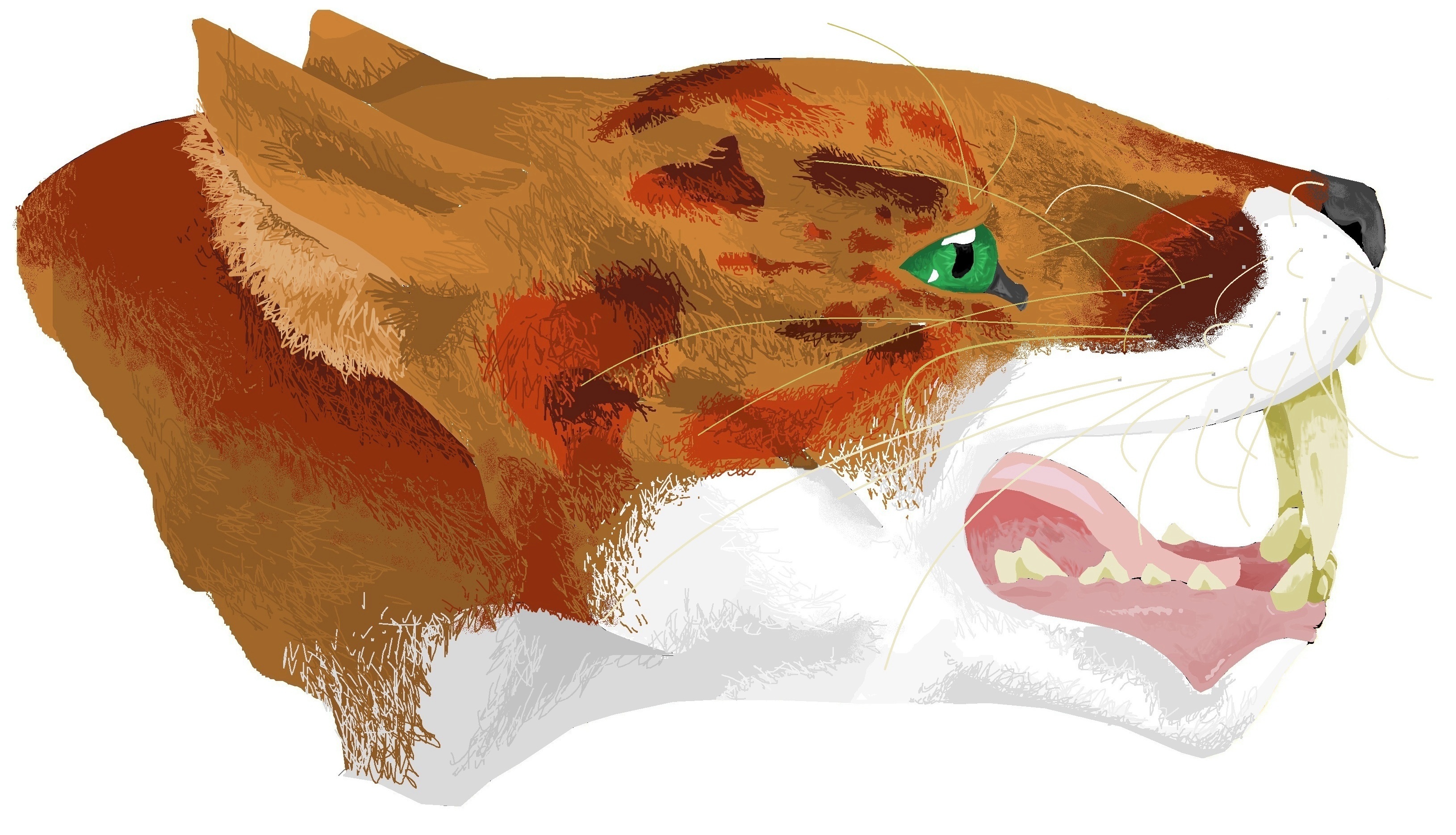

Hoplophoneus, a nimravid feliform (related to cats but not a true cat), South Dakota, 35 million years ago.

Barbourofelis, a barbourofelid feliform (related to cats but not a true cat), Florida, 14 million years ago.

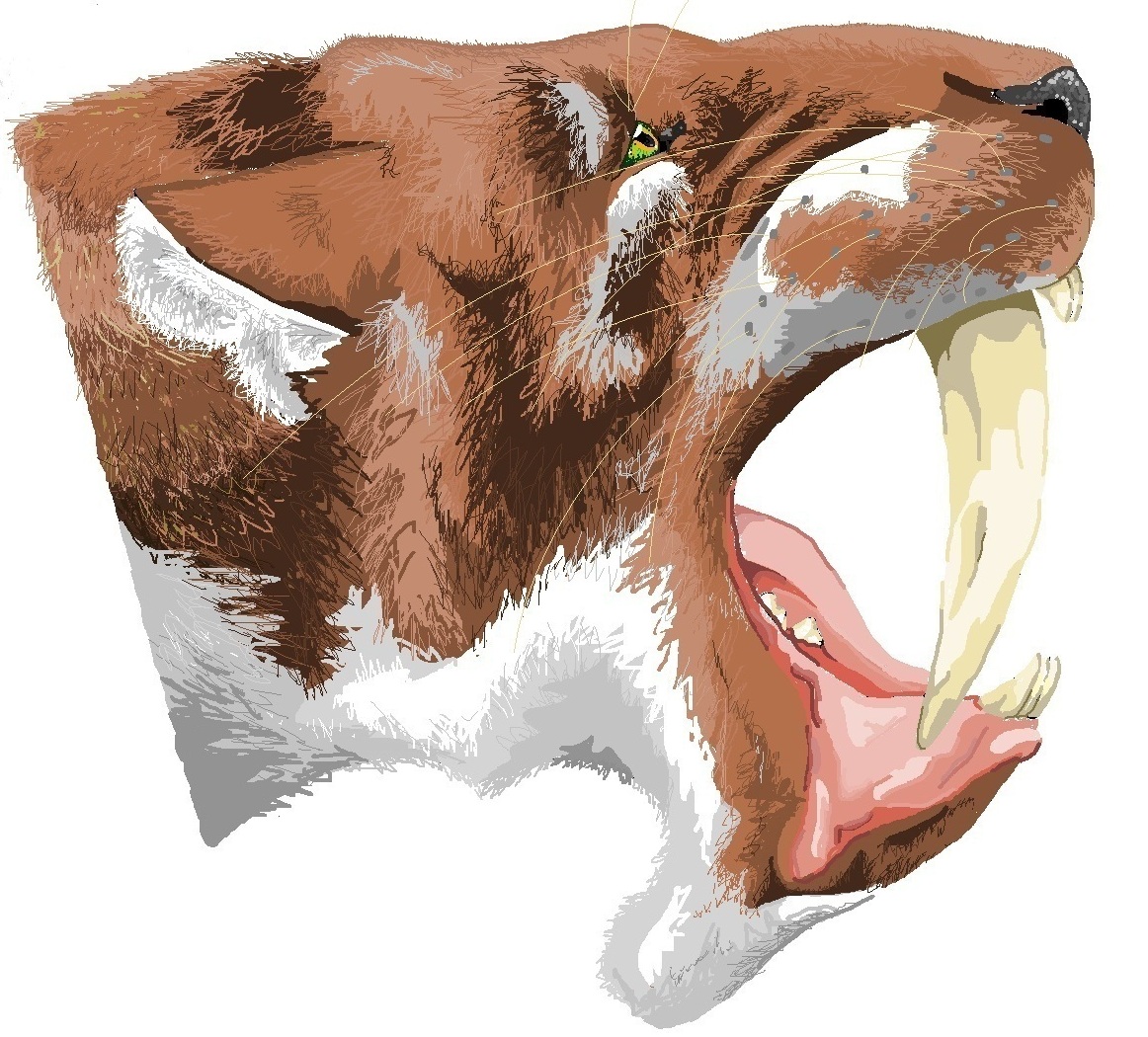

Smilodon, the famous “saber-toothed tiger,” and the only true cat on this list, California, 2.5 million years ago.

So, if saber teeth have happened so many times independently throughout history, why don’t any creatures have them now? The answer is simple yet somewhat unsatisfactory–coincidence. But don’t fret–saber teeth are likely to show up again in the future! Just you wait a couple million years, my money is on either the descendants of lions or of mandrills.

* These animals are listed in order of evolutionary distance from modern cats, and then by age.

Additional pictures

Ichthyosaurs and Dolphins

Above: Ichthyosaurs, aquatic reptiles. These evolved from a terrestrial reptile ancestor, so they’re secondarily aquatic.

Above: Dolphins, aquatic mammals. These evolved from a terrestrial mammal ancestor, but converged on almost the same body style as ichthyosaurs. Ichthyosaurs had a vertical tail fluke and swam by moving their tails side to side like a fish, while dolphins have a horizontal tail fluke move their tails up and down. This is due to the fact that dolphins’ land-living ancestors had already evolved an upright, rather than sprawling, stance, while ichthyosaurs’ land-living ancestors sprawled. Contrast the way a cheetah’s spine flexes while running with the way a lizard’s does, and imagine the consequences of putting those animals in the water.

Ornithomimids and Ratites

Above: The skeleton of Struthiomimus, a non-avian dinosaur. It had a long neck with a tiny head, a toothless beak, reduced arms, and powerful legs for running.

Above: The skeleton of an ostrich. It evolved from a small, flighted bird ancestor (so it’s secondarily flightless) and converged on the same body plan as Struthiomimus.

Image Credits: Dakosaurus Plioplatecarpus Mongoose Ferret Thylacines Skull Comparison Gorgonops Lotheridium Thylacosmilus Machaeroides Hoplophoneus Barbourofelis Smilodon Ichthyosaurs Dolphins Struthiomimus Ostrich