The last in the trilogy of group overviews on this blog, in this post I’ll be going over the main types of Mesozoic aquatic reptiles. However, the phylogeny of many of these groups, especially turtles and their relatives, is still pretty uncertain, so I won’t include a tree. This isn’t a comprehensive list, but I’ll cover the most charismatic and prolific groups; groups not covered include mesosaurs, protorosaurs, and thalattosaurs.

Ichthyosauromorphs

One of the most famous groups of aquatic reptiles, these appeared at the beginning of the Triassic period, and led the Mesozoic Marine Revolution, a radiation event that resulted in much more complex food webs and predator-prey interactions in the ocean than had been seen in the Paleozoic. Giant Triassic ichthyosaurs like Shastasaurus and Shonisaurus were the largest marine reptiles ever, at around 20 meters long and 30-70 tonnes, the size of a sperm whale.

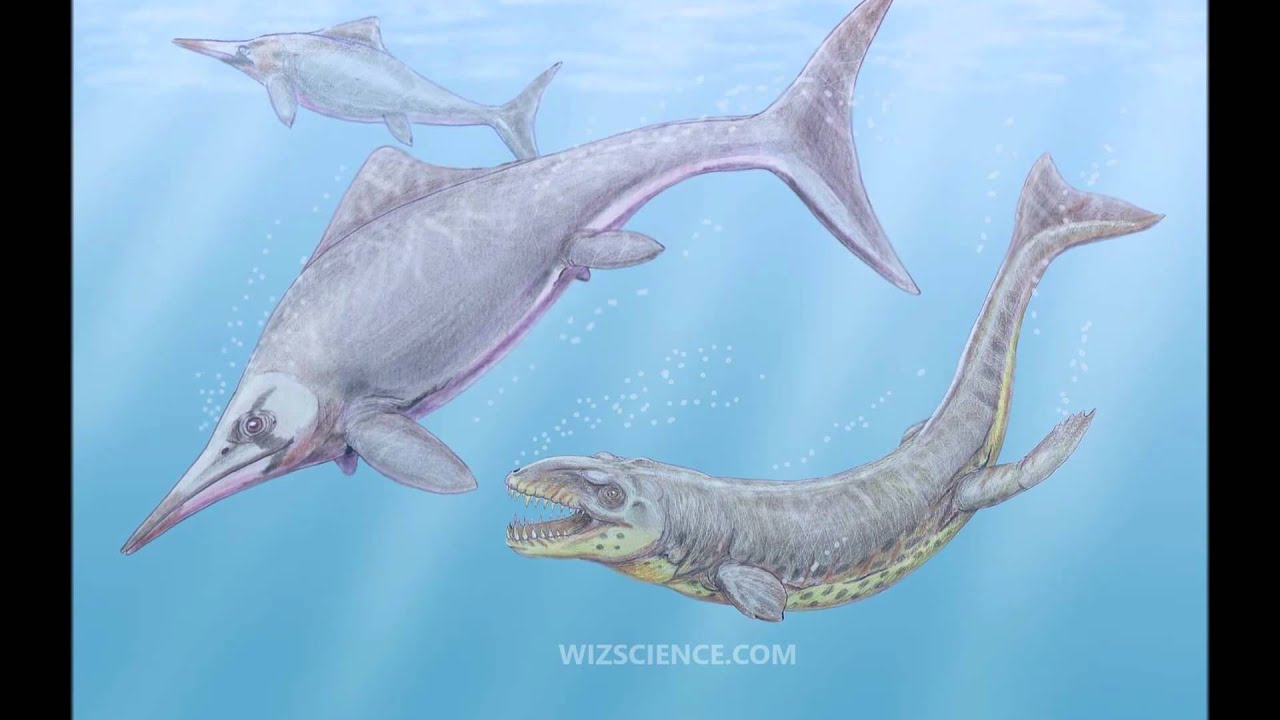

Ichthyosaurs were warm-blooded, blubbery, often countershaded, and gave live birth tail-first similarly to modern cetaceans (to prevent the infant from drowning before it’s completely free of the mother). They filled a variety of niches in the Triassic and Jurassic, including durophagy (cracking tough shells to get at the soft prey inside), ram feeding, suction feeding, and apex predation, but as other groups of aquatic reptiles diversified in the Jurassic and Cretaceous, ichthyosaurs fell to the wayside. Here’s a PBS Eons episode on ichthyosaurs and the Mesozoic Marine Revolution.

Ichthyosaurs

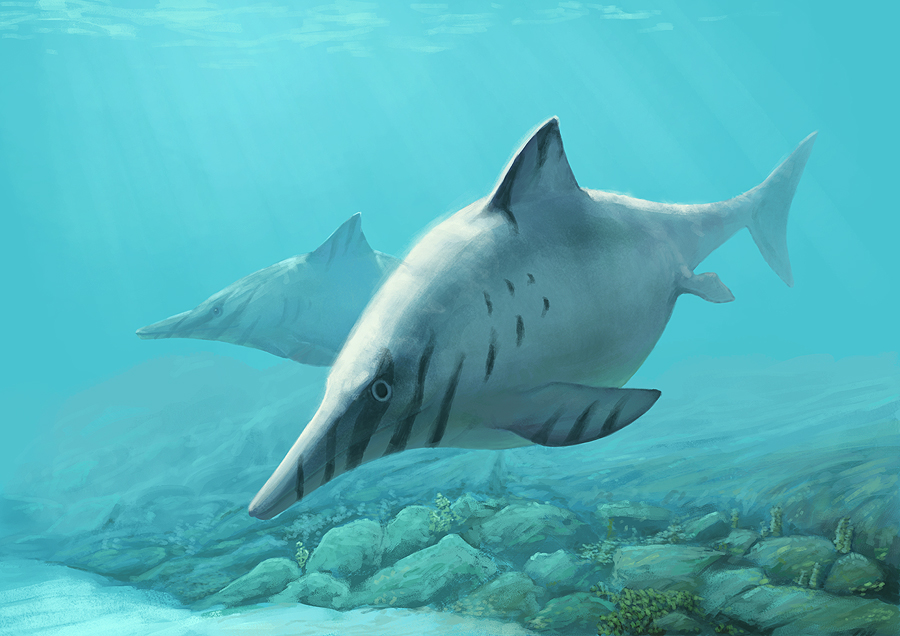

These are the classic dolphin-shaped animals, with long snouts and big eyes. More primitive forms had less-developed hypocercal tail fins and body shapes more akin to swimming lizards, probably swimming in a more anguilliform fashion, while advanced forms had homocercal tails and were capable of very fast thunniform swimming. As mentioned above, Shastasaurus holds the record for the largest marine reptile ever, while Temnodontosaurus and Ophthalmosaurus hold the record for largest eyeball ever–the size of a soccer ball! Some famous members include Shastasaurus, Shonisaurus, Ichthyosaurus, Ophthalmosaurus, Temnodontosaurus, and Stenopterygius.

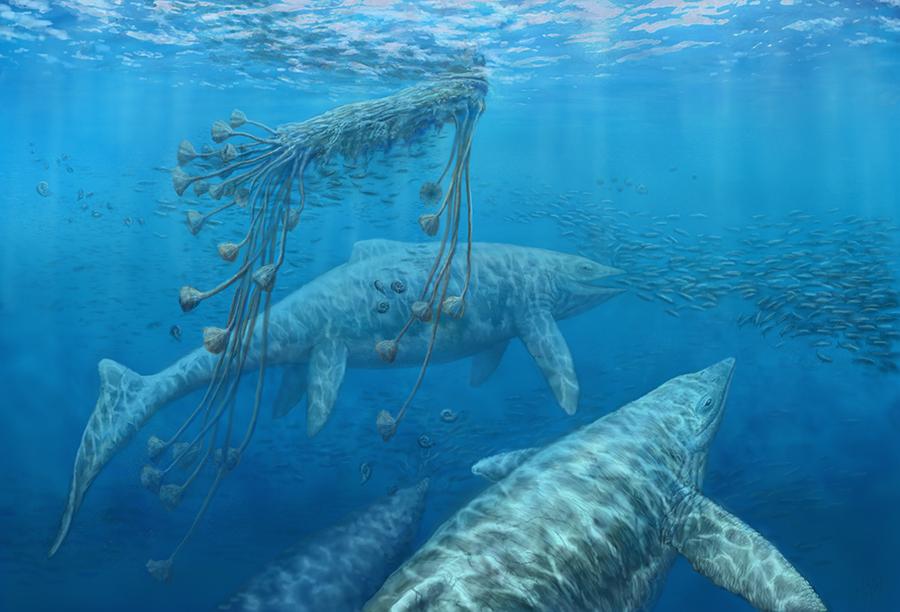

Above: The giant whale-like ichthyosaur Shastasaurus, from the Middle-Late Triassic (235-205.6 million years ago), was toothless and may have been a suction feeder.

Above: The dolphin-like Ophthalmosaurus, from the Middle-Late Jurassic (165-160 million years ago), was also toothless, and preyed on squid. Its giant soccer-ball-sized eyes were mostly hidden by the surrounding flesh and were good at seeing in the low-light conditions of deep water where its prey lived.

Image credits: Shastasaurus Ophthalmosaurus

Hupehsuchians

Hupehsuchians were a strange, short-lived group of ichthyosauromorphs from the Early Triassic. Some famous members include Hupehsuchus and Eretmorhipis, pictured below.

Above: Hupehsuchus was a 3-foot-long hupehsuchian from Early Triassic China (~250 million years ago). It may have been a ram feeder with a pelican-like throat pouch.

Above: Eretmorhipis, another 3-foot-long hupehsuchian from about the same time and place as Hupehsuchus. It had a tiny head, wide fan-like flippers, and a row of prominent osteoderms along its back.

Image credits: Hupehsuchus Eretmorhipis

Sauropterygians

The next group to show up were the sauropterygians (meaning “reptile wing”), a group that included the famous plesiosaurs (think Nessie) and pliosaurs (including Liopleurodon) as well as the lesser-known nothosaurs and placodonts. This group also may include turtles, but that relationship is still disputed.

Nothosaurs

Nothosaurs arose in the Early Triassic and went extinct at the end of that period. They resembled swimming lizards and probably filled the niche that seals do today, catching prey in the water but hauling ashore to rest and sunbathe. They may be directly ancestral to the later plesiosaurs, but this is disputed.

Above: Nothosaurus attacking the tiny ichthyosaur Mixosaurus in the Middle Triassic of China.

Placodonts

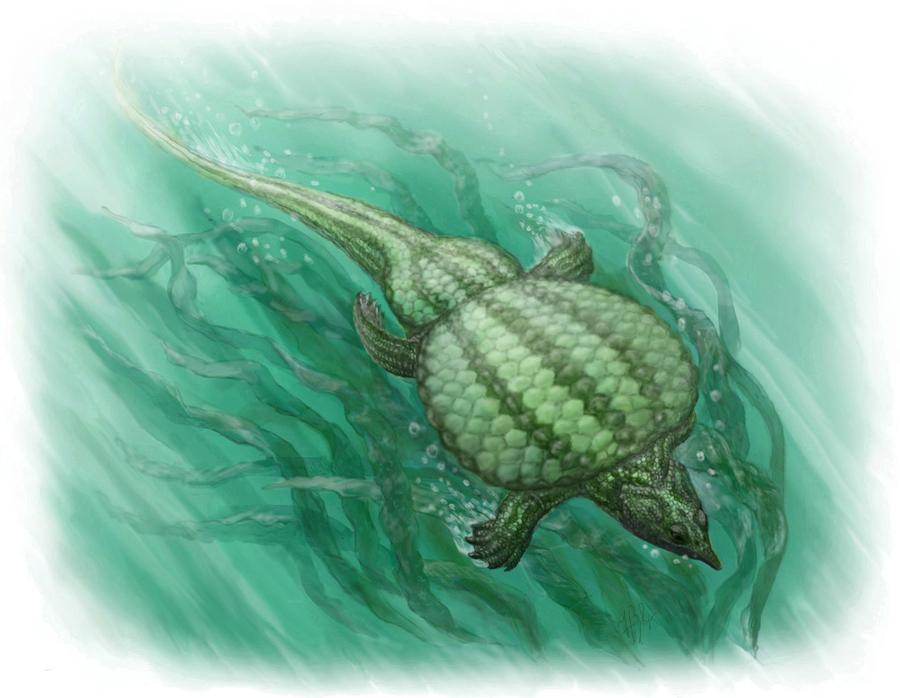

Not to be confused with placoderms (plate skin), which are armored fish from the Devonian period, placodonts (plate teeth) were a very strange group of Triassic sauropterygians. Early members like Placodus resembled barrel-chested swimming lizards, but later members developed turtle-like carapaces for protection, probably a few times independently. They aren’t directly ancestral to turtles despite the resemblance. True to their name, placodonts often had flat teeth, indicating a durophagous diet of crushing shellfish. Famous members include Placochelys, Psephoderma, and Henodus.

Above: Psephoderma, a placodont with a two-part shell from the Late Triassic (about 210 million years ago).

Above: Henodus, a filter-feeding freshwater placodont from the Late Triassic. Why are you laughing? Stop laughing!

Plesiosaurs

Plesiosaurs come in two main flavors: the pliosauromorphs, with short necks and big, crocodile-like heads, and the plesiosauromorphs, with long necks and tiny heads. Both have stiff, round bodies with four oar-like flippers and short tails. New research shows that they probably swam with the back flippers lagging the front, using the wake created by the front flippers to move more efficiently, similarly to how a dragonfly’s four wings move when it flies. Pliosauromorphs and plesiosauromorphs do not count as true clades; plesiosaurs have evolved both the long-necked and short-necked body plans multiple times in their evolution, so having a long neck doesn’t necessarily mean one is more closely related to other long-necked plesiosaurs than to short-necked ones.

Plesiosaurs were warm-blooded and gave live birth in the water, as evidenced by a fossil found of a pregnant Polycotylus with preserved fetus. They were incapable of raising their necks above the water like a swan or of hauling ashore like a sea turtle, instead spending their entire lives almost fully submerged. Plesiosauromorphs hunted small prey, cruising slowly and using their long necks to efficiently grab prey without moving too much (similar to the lawn-mower strategy of the land-based diplodocoid sauropods). Pliosauromorphs were apex predators of the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, but were replaced by mosasaurs in the Late Cretaceous. Famous examples of plesiosauromorphs include Plesiosaurus, Elasmosaurus, and Styxosaurus; famous examples of pliosauromorphs include Pliosaurus, Kronosaurus, and Liopleurodon.

Above: Kronosaurus (meaning “Kronos’s reptile” or “time reptile”), a giant pliosauromorph from the late Early Cretaceous. It was around 36 feet long and weighed up to 13 tonnes, the size of a Tyrannosaurus.

Above: Elasmosaurus (meaning “thin plate reptile”), depicted as a school-hunter (a rival, but less accepted, hypothesis to the lawn-mower hypothesis). Here it is shown with a diamond-shaped fin on its tail; this is known from a single fossil that belongs to a private collector, so its veracity is unknown. Elasmosaurus was 34 feet long, but 23 feet of that was neck!

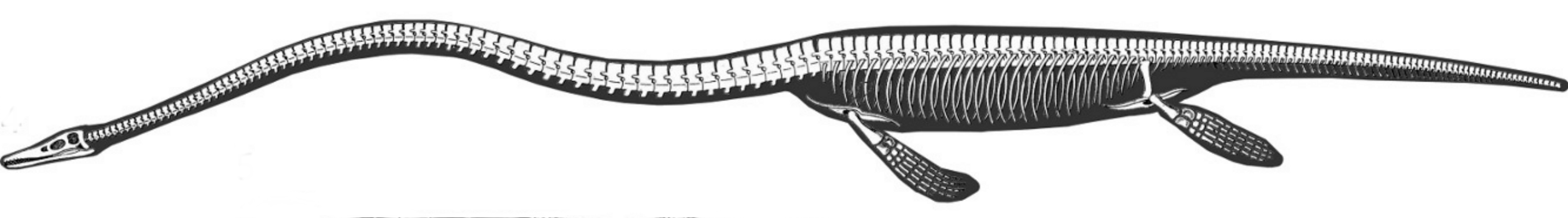

Note: Compare the skeletons of two very long-necked animals with very different lifestyles, Elasmosaurus and Tanystropheus:

Above: Elasmosaurus, with its 72 neck vertebrae.

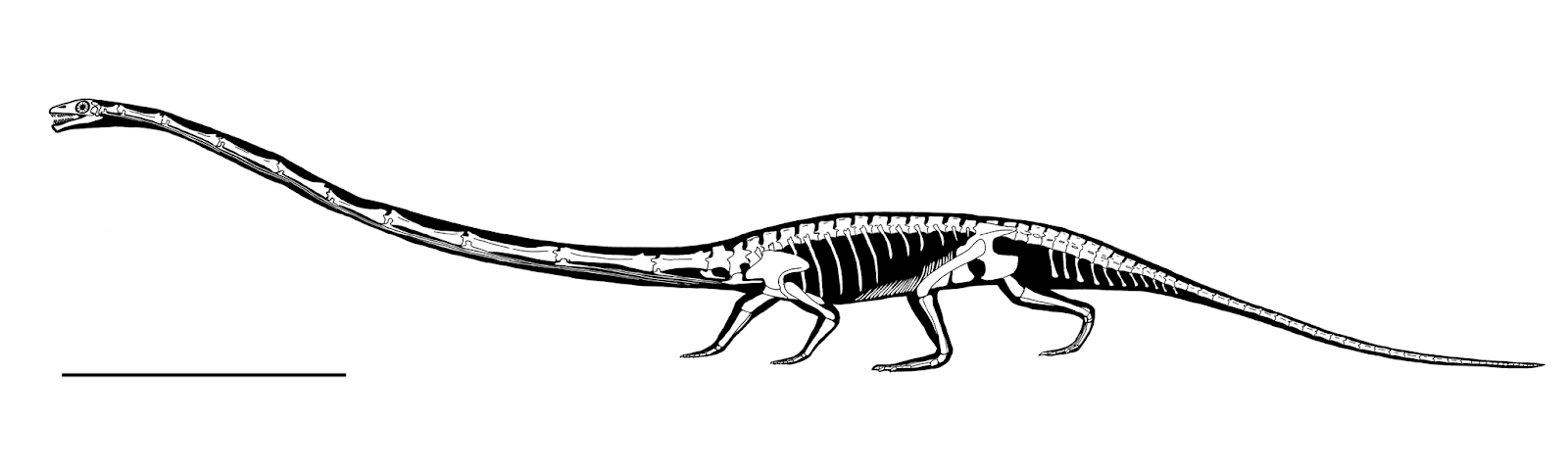

Above: Tanystropheus, with its 12 super-elongated neck vertebrae.

Two things are very interesting about these contrasting strategies. One is that it’s evolutionarily really easy to just copy and paste vertebrae, or delete vertebrae; the number of vertebrae an animal has is a pretty homoplastic trait. The second thing to note is how we can infer the animal’s lifestyle from its neck vertebrae. Elasmosaurus’s neck was very heavy and flexible, but not very strong. The heaviness would’ve been useful for maintaining neutral buoyancy in the water, and the flexibility indicates it needed to be able to bend its neck agilely and quickly but did not need to be able to lift the neck up very high or support itself. Tanystropheus’s neck was very light and stiff, indicating that it didn’t need to bend much, but it needed to be able to hold its neck up in the air for long periods of time.

Testudines (turtles)

I won’t go into much detail here because you’re probably pretty familiar with sea turtles, but I will briefly go over their evolutionary history.

Turtles are a super bizarre group whose relationship to other reptiles is still uncertain. Their arms and legs are actually inside their rib cage, and their inflexible exterior means they need a special mechanism in order to breathe. Early stem-turtles like Eunotosaurus from the Late Permian and Pappochelys from the Middle Triassic just looked like barrel-chested lizards; Odontochelys from the Late Triassic looked indisputably like a turtle. Here’s a great video by PBS Eons that goes into more detail on turtle evolution. There’s also a whole Common Descent Podcast episode (Episode 60) on turtle evolution that I highly recommend.

Above: Archelon, the largest known sea turtle, from the Late Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway, the ocean that bisected North America. It was about 5 meters long and weighed around 2.2 tonnes. The largest living turtle, the leatherback, is about 2 meters long and a bit less than 1 tonne.

Turtles do the four-paddle thing a bit differently than plesiosaurs. Turtles’ front flippers provide propulsion while their rear flippers are much smaller and are used for steering, while all four of plesiosaurs’ flippers were about the same size.

Image credits: Nothosaurus Psephoderma Henodus Kronosaurus Elasmosaurus Elasmosaurus skeletal Tanystropheus skeletal Archelon

Archosaurs

Archosauria is the group that includes dinosaurs (including birds), crocodilians, and phytosaurs, and their relatives. Semi-aquatic non-avian dinosaurs are rare; fully-aquatic dinosaurs are nonexistent. This is because they were oviparous (egg-laying) and amniotic (their eggs have waterproof shells that need to be laid on land, as opposed to the soft membranous eggs laid in the water by amphibians and fish). Phytosaurs and most crocodilians were semi-aquatic for the same reason, but one group of crocodilians, the Metriorhynchidae, may have developed viviparity (ability to give live birth) and become fully aquatic.

Phytosaurs

Phytosaurs were a group of Triassic-exclusive crocodile-mimics that are less closely related to birds and true crocs than birds and crocs are to each other. They’re distinguishable from crocs by their nostrils being up by their eyes instead of at the end of the snout.

Above: Redondasaurus and babies scare off some Coelophysis in Late Triassic New Mexico.

Phytosaurs were very successful, with a worldwide distribution in the Triassic, and probably filled the same niche that modern crocodilians do today, that of large semi-aquatic ambush predator. However, they went extinct shortly after the end-Triassic extinction event along with a lot of other archosaurian diversity.

Image credit: Redondasaurus

Thalattosuchians

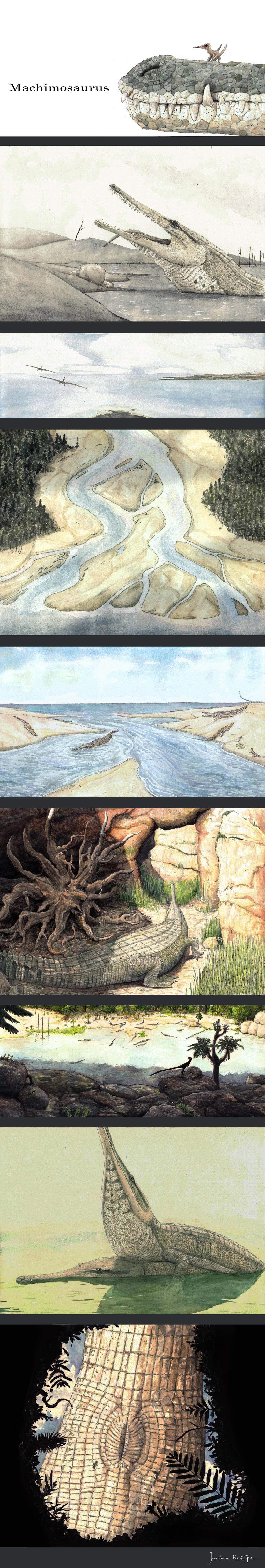

Thalattosuchians (meaning “sea crocodile”) were a group of semi- and fully-aquatic crocodylomorphs from the Jurassic to Early Cretaceous. They come in two main flavors: the teleosaurids, which were semi-aquatic piscivores, but more adapted for swimming than modern crocs, and the metriorhynchids, which were fully aquatic predators with paddle-like limbs that were probably incapable of terrestrial locomotion.

Above: Machimosaurus, a giant teleosaurid from Late Jurassic Switzerland, doing various teleosaurid things. That last picture is the female’s cloaca; she is about to lay eggs in a hole.

Above: Dakosaurus, a metriorhynchid, harassing an ichthyosaur in Late Jurassic England. I think the convergence between metriorhynchids and the much later mosasaurs is pretty incredible; see my post on convergent evolution. We don’t have direct evidence of viviparity or oviparity in metriorhynchids, but looking at their skeleton it could really go either way. Perhaps they retained knees in their back flippers in order to better haul themselves onto land to lay eggs like sea turtles, or perhaps they were in the process of losing their knees when they went extinct. No other archosaurs are thought to have given live birth, so assuming metriorhynchids had to lay eggs on land is probably the conservative hypothesis.

Image credits: Machimosaurus Dakosaurus

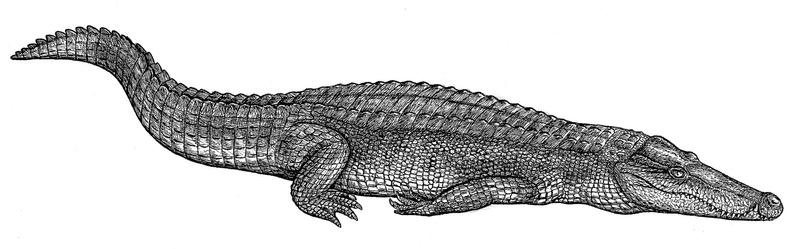

Suchians

Since we covered phytosaurs, I would be remiss not to talk about suchians, or true crocodilians. Pseudosuchians, or all animals more closely related to living crocs than to birds, were extremely diverse and largely terrestrial in the past, getting their start in the Triassic and maintaining a lot of diversity throughout the Mesozoic. The modern semi-aquatic ambush predator body plan appeared in the Early Jurassic with animals like Calsoyasuchus and continued almost unchanged into the present day.

Above: Goniopholis, a Late Jurassic crocodyliform from Europe and Africa. If you told me this was a living genus, I wouldn’t be surprised–it’s so similar to modern crocs!

Image credit: Goniopholis

Dinosaurs

You’re probably familiar with most semi-aquatic living birds such as penguins, seabirds, waterfowl, etc., so here I’ll just cover some famous fossil forms, focusing especially on semi-aquatic non-avian dinosaurs, since they’re so uncommon. We will start with the most birdlike and get less birdlike as we move along.

Above: Hesperornis, a toothy, penguin-like semi-aquatic bird from Late Cretaceous North America. It was discovered by the famous Bone Warrior Othniel Charles Marsh, and its toothiness led him to say, “the fortunate discovery of these interesting fossils [Ichthyornis and Hesperornis] does much to break down the old distinction between Birds and Reptiles.”

Above: Halszkaraptor, a semi-aquatic dromaeosaur with a ridiculously long neck. It probably dove for fish like a cormorant and propelled itself through the water using its wings like a penguin.

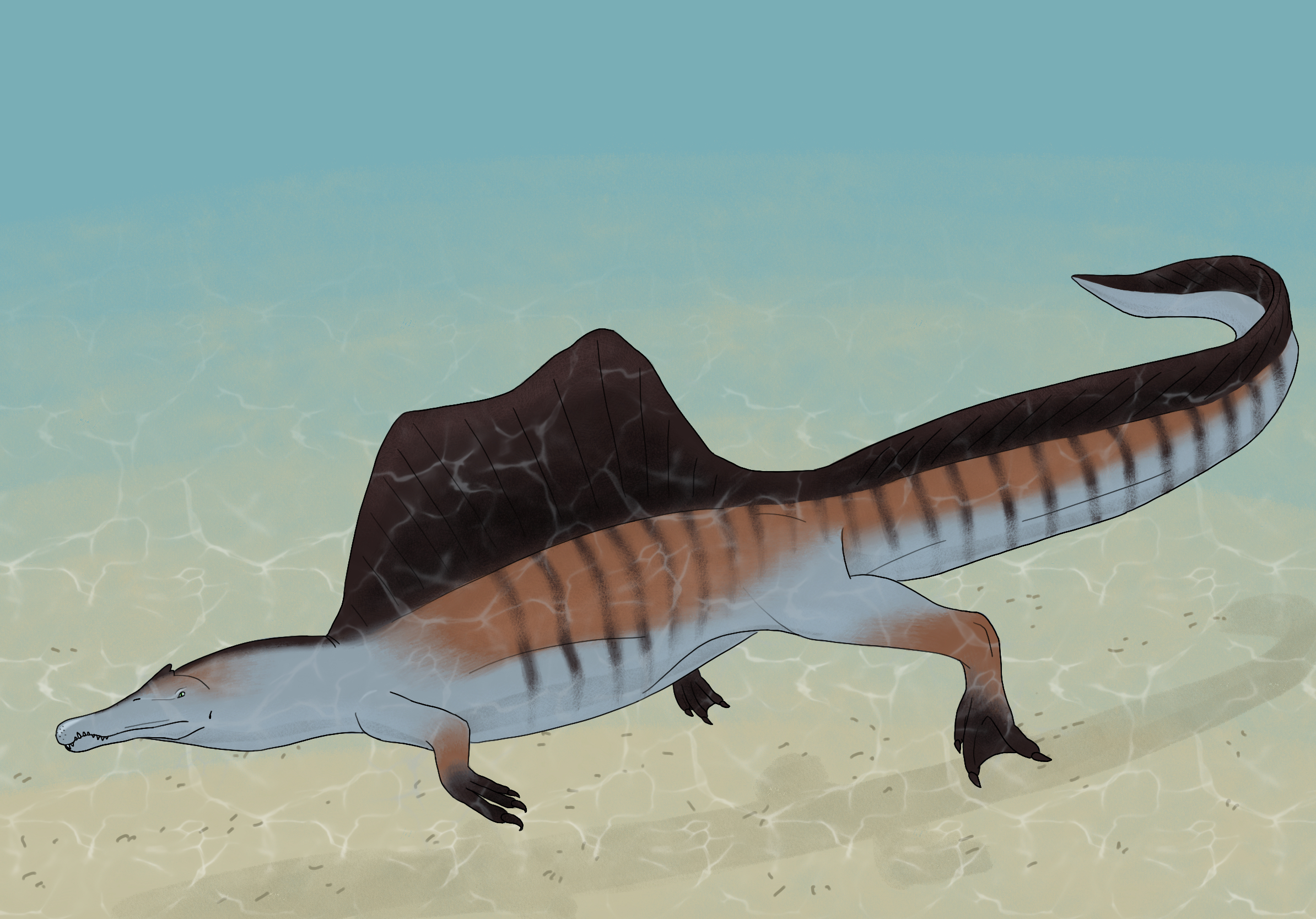

Above: Spinosaurus, a spinosaur from Early Cretaceous Egypt. This group of giant theropods had numerous similarities to crocodiles, such as the long snout ending in a toothy rosette lined with conical teeth, good for grabbing fish, and the pressure-sensitive neurons in the tip of the snout. Spinosaurus has been the center of attention recently, since the discovery of its new swimmy tail has re-awakened the long-standing debate over the degree to which it was aquatic. It definitely ate fish, but did it wade like a heron, ambush like a croc, or pursue like a shark? Hopefully more fossil material will show up and let us know!

Above: Liaoningosaurus, a tiny, foot-long ankylosaur from Early Cretaceous China that was found with pieces of fish preserved in its gut.

Above: Lurdusaurus, a hippo-like ornithopod from Early Cretaceous Niger. It had particularly heavy bones that would’ve allowed it to walk along the bottom rather than swim.

Image credits: Hesperornis Halszkaraptor Spinosaurus Liaoningosaurus Lurdusaurus

Squamata (lizards)

Lizards and snakes are lepidosaurs, the sister clade to archosaurs. They’ve taken to the seas in various guises since the Cretaceous.

Mosasaurs

By far the most impressive marine squamates (and probably the coolest aquatic reptiles ever) are the mosasaurs, relatives of the Komodo dragon that converged on the same body plan as metriorhynchids did millions of years earlier (see my post on convergent evolution). Mosasaurs are another group that adapted to give live birth, allowing them to spend their whole lives in the water. They arose in the Late Cretaceous as the pliosaurs and ichthyosaurs were dying out, and quickly grew to enormous sizes to assume the role of apex predator. Since they were lizards, they may have had forked tongues, double penises, and a third pineal eye (yes, these are traits that existing lizards have. No wonder boys like them). Famous examples of mosasaurs include Mosasaurus, Tylosaurus, Platecarpus, Clidastes, and Globidens (which was a durophage that had globular teeth for crushing shells).

Above: The giant mosasaur Tylosaurus breaching to catch a Pteranodon in the Western Interior Seaway of Late Cretaceous North America.

Marine Iguanas

A relatively new addition to the marine reptile roster is the Galapagos marine iguana, which diverged from its land-based relatives in the Miocene about 8-10 million years ago. They don’t really look that different than terrestrial iguanas, but they act very differently, eating algae almost exclusively.

Above: A Galapagos marine iguana eating algae. I sort of have to agree with Charles Darwin’s nickname for them, “imps of darkness”. I wonder if Godzilla’s face and texture was inspired at all by these creatures.

Sea Snakes

Snakes diverged from other lizards in the early Late Cretaceous and almost immediately some of them took to the water.

Above: Palaeophis, a giant sea snake, attacking a baby Basilosaurus, a primitive whale, in Eocene North America. That snake is about to have his arse handed to him by mama whale. Palaeophis lived from the Cretaceous all the way to the Eocene and is an unlikely megafaunal survivor of the extinction that killed the dinosaurs. It’s only known from a bunch of vertebrae (most fossil snakes are), so the tail fluke and vestigial legs depicted here are just an educated guess.

Above: The living yellow-bellied sea snake, showing off its flattened, ribbonlike body. They are optimized for swimming and move very awkwardly on land. They have nostrils on top of their snout, can partially respirate through their skin underwater, and can stay submerged for up to 8 hours.

Image credits: Tylosaurus Palaeophis Marine iguana

Here ends our dive into the evolution of aquatic reptiles! Even though many of the most charismatic members are now extinct, this group was so important in shaping the ecology of the oceans that still persists today. I hope you enjoyed the journey and learned something new.