By now, I’m sure you’ve seen or heard about reconstructions of fluffy or feathery dinosaurs. Lately, paleoartists have been going crazy with the speculative fluffy integument of everything from Tyrannosaurus:

to armored archosauromorphs like Doswellia:

But which dinosaurs (and archosauromorphs) actually had fluff? Which ones definitely had fluff, and which are more speculative? And which ones were definitely scaly? In this post, I’ll go over the main candidates for fluff, what type of fluff to expect, and how we know what we know.

Concepts

There are two main concepts that are important to the discussion of paleo integument (the outermost layer of an animal, i.e. its skin, fur, feathers, scales, osteoderms, etc): thermoregulation and phylogenetic bracketing. I’ll describe both in detail before we jump into individual examples.

Thermoregulation: Why be fluffy?

Many mammals are fluffy. Most birds are fluffy. Lizards, crocodilians, fish, and naked mole rats are not fluffy. What’s the correlation here? Thermoregulation. Fluffy creatures are endothermic (warm-blooded), keeping their core temperature elevated relative to the environment all the time. Fluff helps them keep the heat in, preventing them from losing too much energy to the environment. As an endothermic animal gets bigger, the square-cube law means that they don’t need as much insulation to stay warm, and may even lose their integument almost entirely over a certain size threshold when they get too warm. This is why elephants, rhinos, and hippos are mostly hairless–they run very warm and a thick fur coat would cause them to fatally overheat.

On the flip side, ectothermic animals tend to be naked. These animals allow their core temperature to fluctuate with the environment, and are able to be more active when warm. For them, fluff would keep heat out! And yes, naked mole rats are actually cold-blooded, a rare example among mammals.

So, if you know a fossil animal was endothermic and smaller than a rhino, there is a good chance it had some kind of insulating coat. (We can sometimes tell if an animal is endo- or ectothermic based on its bone histology, or bone growth rings, without having directly preserved evidence for fluff.)

Note: Why are humans hairless?

This is actually still a matter of some debate, but these are the main theories:

- Humans evolved in hot conditions with a lot of direct sunlight exposure, namely the African savanna. Since we walk upright (why we do that is another story), having head-hair protects us from the vertically-shining sunlight, and having minimal body hair allows us to be cooled more effectively by the horizontally-blowing wind. Armpit and pubic hair were retained to help us to be smellier (no kidding–the smells involved are thought to be pheromones related to sex).

- It’s a display / sexual selection thing, like a peacock’s tail, which serves no function other than to be sexy. Clear, smooth skin is associated with good health, so maybe it makes sense that being able to see it better is more attractive.

- Hair is a breeding ground for lice and other ectoparasites. While this is true, other animals just live with their ectoparasites, so it doesn’t make much sense why humans should be special in jettisoning their hair.

Phylogenetic Bracketing: Who is capable of growing fluff?

To answer this question, we will use the principle of phylogenetic bracketing. That means that if two animals on different branches of the tree of life are known to have a trait, then all animals in between them on the tree are also candidates for this trait. This is because it’s likely that the last common ancestor of the two probably had the trait, which means that all of its other descendants could have it too.

For example, let’s say your dad’s cousin’s kid (your first cousin once removed) has violet eyes. And your dad’s brother’s kid (your first cousin) also has violet eyes. There’s a good chance the two of them got their violet eyes from the same place, the last common ancestor they shared, which is your great-grandfather. That means that you (and all your great-grandfather’s other descendants) also probably have the gene for violet eyes, even if you don’t show it.

So who are the distant fluffy cousins in the case of archosaurs? Well, we have fossilized fuzz from pterosaurs, and birds are clearly fluffy. That means that phylogenetically, everything in between, which includes all dinosaurs, was capable of producing fluff. Then why don’t we see art of fluffy Stegosaurus or Triceratops? Well, not everyone who could produce protofeathers actually did. Now that we’ve covered the main concepts surrounding paleo fuzz, let’s dive into specific examples.

Triassic Archosauromorphs

Our story begins way back in the days before the dinosaurs, shortly after the Great Dying, when the reptile family was still sorting itself into the clades we’re familiar with today. New research from May of 2019 shows that some of the earliest archosauromorphs closest to the base of the archosaur (birds, crocs, and dinosaurs) family tree were very much endothermic. Since the earliest ancestors were warm-blooded, we can infer that this was the ancestral condition, and that means the cold-blooded crocodilians of today became ectothermic secondarily–that is, they evolved from warm-blooded ancestors. And since these early archosauromorphs were warm-blooded, at least the small ones probably had some kind of insulating coat.

Above: Euparkeria, a small archosauriform from Middle Triassic South Africa, reconstructed with a fluffy coat of protofeathers. Doesn’t it make you want to pet him?

Above: Teraterpeton, a small archosauromorph from Late Triassic Canada. It looks super birdlike in this depiction, but its body plan was more like that of a lizard, with four sprawling limbs and long, clawed toes.

So, when drawing Triassic archosauromorphs, it’s reasonable to depict a good amount of fuzz, especially when the creature is small. However, no direct fossilized fuzz has been found in these groups, so if you don’t like how it looks, you could argue your case. Also, note that primitive archosauromorph fluff is not feathers–only dinosaurs are known to have complex, branching feathers, but for archosauromorphs simple filaments (called protofeathers) are fair game.

Pterosaurs

As I mentioned above, we have direct fossilized evidence that pterosaurs were fluffy, sporting a coat of pycnofibres that are homologous to feathers.

Above: Sordes pilosus (meaning “dirty hairy”–I’m not kidding), a basal pterosaur from Late Jurassic Kazakhstan, was found with beautifully preserved pycnofibres.

Above: Jeholopterus (meaning “Jehol wing”), an anurognathid pterosaur from Middle to Late Jurassic China, found with directly preserved pycnofibres. Anurognathids (meaning “tailless jaw”) were a group of small, nocturnal, short-tailed, short-faced pterosaurs that probably filled the same niche that bats do today.

Though pycnofibres weren’t as complex in shape as true feathers, new research shows that there were a few varieties that served different functions. Some were for insulation, some for aerodynamics, some for sensing like whiskers, and some for display.

What about giant pterosaurs?

The evidence shows that pterosaurs were ancestrally fluffy and endothermic, but is there a case to be made that giant pterosaurs secondarily could have lost their fluff? Actually, probably not. Quetzalcoatlus northropi, the largest known pterosaur, weighed something like 200 kg (440 lbs), which is extremely large for a flying creature, but not that large compared to other animals known to be very fluffy. For example, a grizzly bear, which has thick fur even in the summer, can get up to 360 kg, so it’s unlikely that Quetzalcoatlus, with its huge membranous wing surfaces, would have faced problems with overheating. In addition, Quetzalcoatlus is estimated to have flown at altitudes up to 4.6 km (15,000 feet) where it would have experienced sub-freezing temperatures.

In conclusion, pterosaurs should always be restored with a full coat of pycnofibres. Totally naked pterosaurs like the ones in Jurassic Park are frankly unacceptable (though that’s not even the worst problem with that depiction–see my post about media portrayals of prehistoric animals).

Dinosaurs

Before the discovery of Tianyulong in 2009 Kulindadromeus in 2014, two small ornithischians (the opposite side of the dinosaur family tree than birds), it was thought that only coelurosaurs (the group containing tyrannosaurs, birds, and everything in between) had feathers. However, Kulindadromeus’s extensive coat, which includes complex feather structures, coupled with its very distant position on the dinosaur family tree compared to coelurosaurs, means that phylogenetically, basically any dinosaur is fair game for feathering. There are a few fossils that directly preserve scales, such as Carnotaurus, various sauropods, Edmontosaurus, etc, but since all of these fall between Kulindadromeus and birds on the family tree, we know that they all must have secondarily lost their fluff.

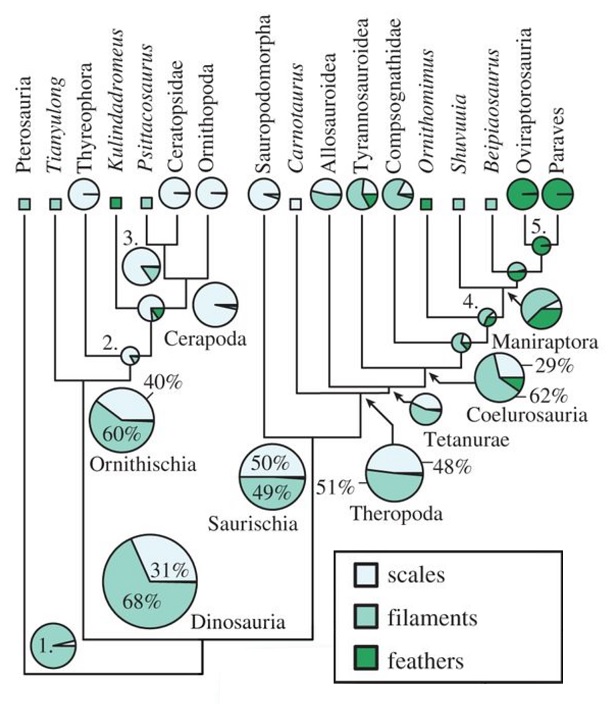

Here is a chart summarizing the known and theorized integuments for ornithodirans:

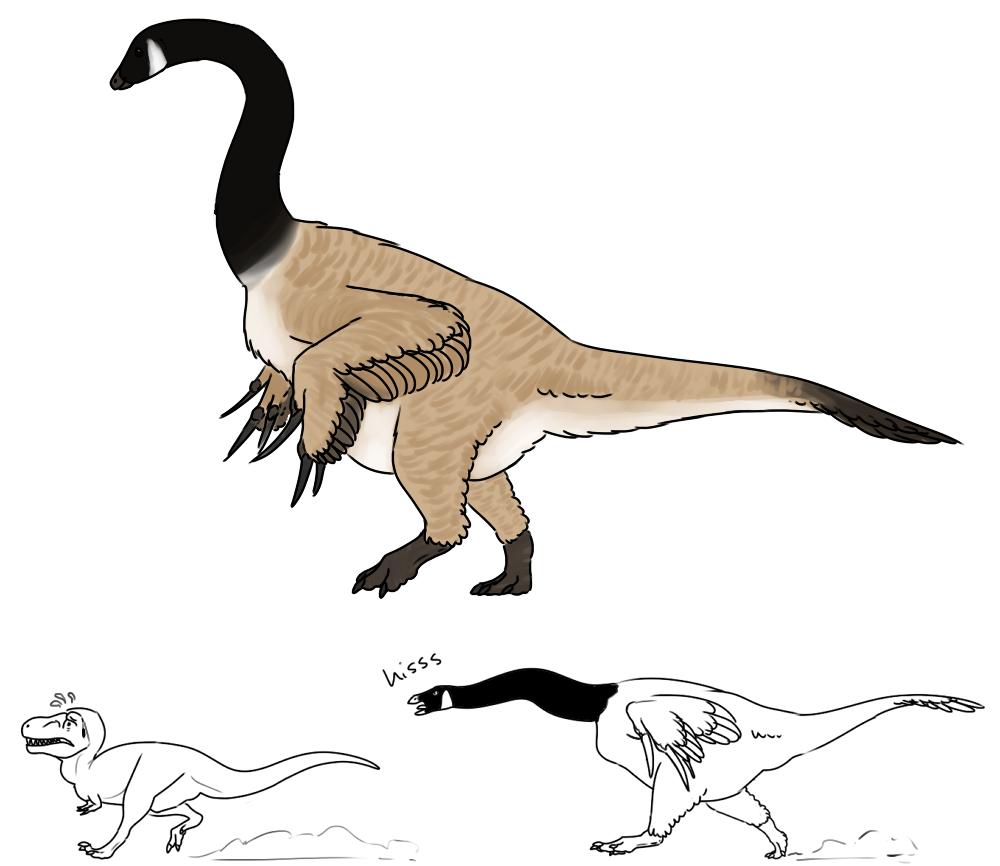

However, even though all dinosaurs have the phylogenetic possibility of having feathers, that doesn’t make it probable in every case. Since a lot of dinosaurs were very large, a fluffy coat would’ve caused them to severely overheat. Mark Witton has a very informative blog post that goes into detail about thermal neutrality (the temperature zones in which an animal doesn’t have to expend extra energy to heat itself up or cool itself down) and how fluffy big animals should probably be. The largest dinosaur we’ve found with directly preserved feathers is Yutyrannus, at up to 1.4 tonnes; anything larger than this should be treated with caution with respect to feathery restorations. As Mark Witton explains, even medium-sized animals like cows are surprisingly cold-tolerant without a very thick coat, and large animals like elephants exist at near-critical temperatures most of the time–a four-hour walk in the sun would cause fatal overheating. This means that the super-fluffy “fatbird” Tyrannosaurus pictured at the beginning of this post is unfortunately out of the question.*

Above: Yutyrannus (meaning “feathered tyrant”), weighing up to 1.4 tonnes, is the largest dinosaur we’ve found that has directly preserved feathers.

* In addition to thermal evidence that Tyrannosaurus should probably be scaly, we now have directly preserved skin impressions of scales.

So what dinosaurs were for sure fluffy, and what’s just speculation?

The chart above does a pretty good job of showing all the directly-known, phylogenetically important feathered dinosaurs: Psittacosaurus and Tianyulong had quills; Beipiaosaurus and Shuvuuia had filaments; and Ornithomimus and Kulindadromeus had complex feathers. There are many other maniraptoriformes (node 4 in the chart) that have been found with beautifully preserved feathers, such as Zhenyuanlong, Microraptor, and Caihong, that sometimes even show what color they were in life. There are also many examples of non-maniraptoran coelurosaurs with protofeathers, such as Dilong and Yutyrannus (tyrannosauroids), and Sinosauropteryx (a compsognathid). Here, I’ll go over a few examples speculative featheriness and how likely they actually are.

Above: Shuvuuia, an insectivorous alvarezsaurid with one-clawed hands from Late Cretaceous Mongolia, which we know was fluffy from direct fossil evidence.

Plateosaurus

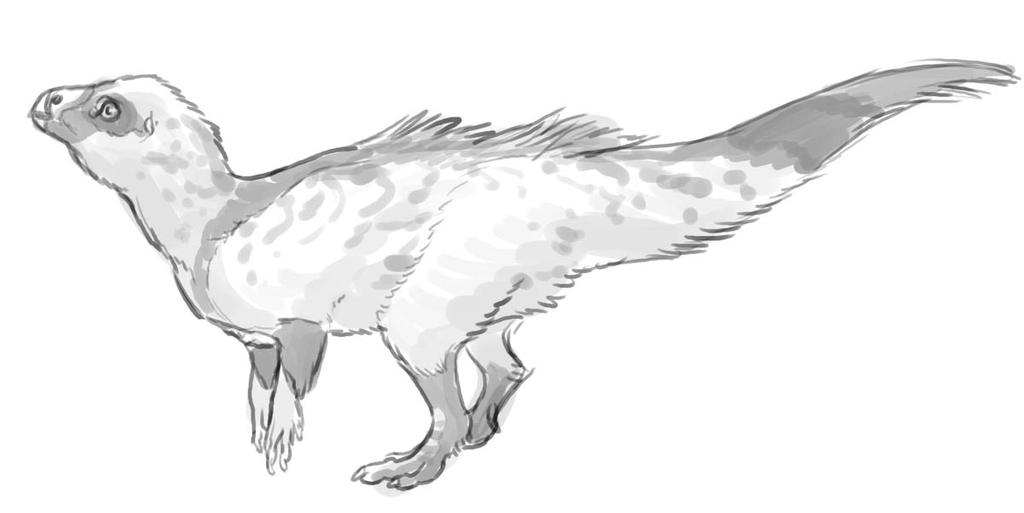

Above: Plateosaurus, a prosauropod (ancestral cousin to the later, giant, long-necked dinosaurs) from Late Triassic Europe and North America, reconstructed with an ostrich-like protofeather coat on the back and tail, with limbs and head bare. Plateosaurus adults weighed up to 4 tonnes, putting it well over the 1.4-tonne Yutyrannus threshold. Furthermore, skin impressions from true sauropods show that they were scaly, meaning that somewhere along the sauropod line, the protofeathers were lost–we just don’t know exactly when. However, as this reconstruction leaves the limbs, neck and head, and underside of the tail bare, it could be argued that those areas can compensate to keep Plateosaurus cool enough–this is how ostriches thermoregulate. I’d give this reconstruction a low but nonzero likelihood.

Above: a more likely, mostly-naked, sparsely-filamented reconstruction of Plateosaurus. Sparse filaments like this (and like those found on elephants) actually help with heat dissipation by providing increased surface area like radiator fins–up to 10% more heat dissipation than a completely bald animal, according to one bit of research. I’d bet on this depiction.

Therizinosaurus

Above: An amusingly-colored Therizinosaurus, a maniraptoran (closely related to birds) from Late Cretaceous Mongolia, restored with a generous feather coat complete with pennaceous wing and tail feathers. A fossil of a very close relative, Beipiaosaurus (listed in the chart above), was found with filaments preserved; however, Therizinosaurus is well over the Yutyrannus threshold at 5 tonnes. I’d give this super-fluffy depiction (ignoring the coincidental coloration) a very low likelihood. Despite this, the super-feathery depiction of Therizinosaurus is by far the most common among paleoartists right now.

Above: A nearly naked Therizinosaurus. I’d say this depiction is more likely than the super-fluffy one, but still less than 50%.

Above: A half-naked Therizinosaurus, again in the manner of ostriches. I’d bet on this depiction.

Irritator

Above: Irritator, a spinosaurid from late Early Cretaceous Brazil, here shown traditionally naked. Probably over 95% of paleoart depictions of Irritator show it being completely scaly.

Above: A rather unusual interpretation of Irritator with a thick coat of protofeathers covering everything except the belly, hands, feet, neck, and snout. Which of these depictions is more likely? Well, Irritator was one of the smallest spinosaurids, at only 1 tonne, putting it under the Yutyrannus threshold, meaning that a full coat of protofeathers won’t cause it to fatally overheat. It was probably semi-aquatic, in which case one could argue that protofeathers are a bad idea–but then again, otters, cormorants, and penguins all sport thick coats even as they dive to depths of several meters. And phylogenetically, Irritator is a tetanuran, which, according to the chart above, have around a 60% chance of filaments. So, in this case, I’d say that the fluffy Irritator is actually not unlikely. I’d give naked Irritator a similar spread–since it lived in a tropical climate and is close to the Yutyrannus threshold, it’s kind of a borderline case. If I were to illustrate Irritator, I think I would go with a middle ground of some areas of display filaments on the arms, tail, and head, but an otherwise mostly scaly body. (Update: I lied. Fluffy Irritator was too much fun to pass up.)

Heterodontosaurus

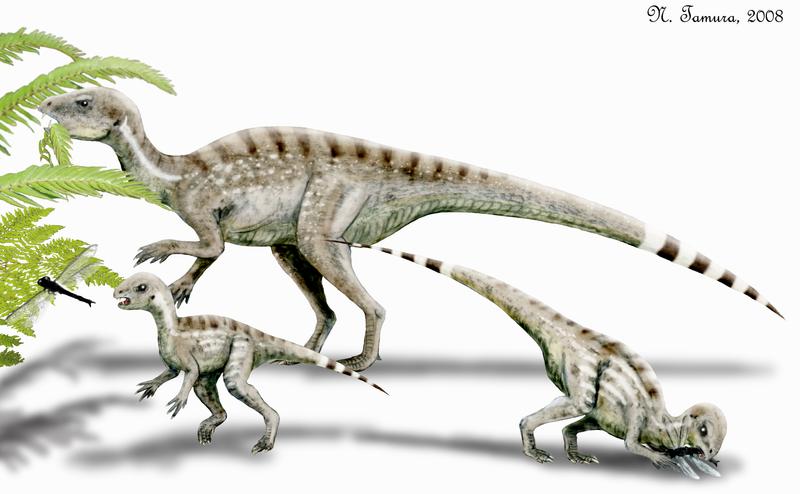

Above: The old-fashioned naked Heterodontosaurus, a very small (2-3 kg) basal ornithischian dinosaur from Early Jurassic South Africa. However, after the discovery of the related Tianyulong in 2009, it became fashionable to depict this dinosaur as some kind of angry, spiky vampire creature, inspired by its fearsome little teeth and its lacrimal (eyebrow) bone.

Above: “Edgy” Heterodontosaurus.

Above: Fluffy Heterodontosaurus. I want one!

So, which Heterodontosaurus is the most probable? In my estimation the fluffy depiction is the most likely, followed by quilly, with the naked depiction a distant last place. Tianyulong is very closely related to Heterodontosaurus and is quilly, but porcupines are closely related to guinea pigs and chinchillas, which are fluffy. In today’s world, quilly creatures are the exception rather than the rule, and fluffy ones are much more common; I would guess that the Mesozoic wasn’t much different. It’s also possible that quills, being harder and larger than fine filaments, fossilize more easily, which is why they seem to be overrepresented among dinosaurs whose integument is known directly.

Conclusion

TL;DR: basically all archosauromorphs are candidates for fluff, phylogenetically, especially the small ones, all the way back to the Triassic and possibly the Permian. Anything over the Yutyrannus threshold of 1.4 tonnes should be fluffed with extreme caution and only under extenuating circumstances. Anything under this threshold, even things we’re used to being depicted as scaly, such as the smallish spinosaurid Irritator, can be fluffed with relative confidence.

The page image depicts the basal ornithodiran (relative of dinosaurs and pterosaurs), Ixalerpeton, in both scaly and fluffy forms. The artist thinks the fluffy version is more likely (I agree, given Ixalerpeton is quite small and almost certainly endothermic), but admits that both forms are artistically pleasing.

But what type of fluff?

Modern birds have five different types of feathers, called Stage 1 through Stage 5 in order of increasing complexity. They look like this:

Stage 1 is a simple filament, which is probably ancestral to all archosaurs. That means basically any archosaur under the Yutyrannus threshold is fair game for sporting these. Stage 2 is a fiber bundle, such as the down feathers found in a pillow. Stage 3 is a simple branched feather. These are known from within Maniraptoriformes–anything more birdlike than Sinosauropteryx, which is known not to have anything more complex than Stage 2. Stage 4 has the feather barbs branching further and sporting barbules, which allow the feather to zipper itself together into a single surface, and Stage 5 is a fully-developed flight feather with an asymmetric leading edge and a smooth texture. Only pennaraptorans (oviraptorosaurs and more birdlike) have Stage 4 and 5 feathers, and probably only flighted paravians would have had Stage 5. From fossilized skin impressions (outlined in Mark Witton’s chart above), we know that true sauropods and the ceratosaur Carnotaurus had secondarily lost their fuzz, so for creatures nearby these on the family tree, feather with extreme caution.

Ornithischians, having inherited the basal filament-producing ability, went on to develop specialized structures not covered in Stages 1-5. Kulindadromeus had two types of unusual feathers alongside Stage 1 filaments: scales with filaments attached to them, and bundles of ribbonlike parallel filaments. However, since ornithischians have no modern descendants, we don’t know what other types of integument are possible. As more discoveries are made, we will doubtless find additional unfamiliar fuzz structures preserved.

Further reading:

Should we make Plateosaurus fluffy?

Updates

Putting my artistic money where my mouth is, here are a couple unusual takes on dinosaur integument.

Above: a fluffy take on Microceratus, a small bipedal basal ceratopsian from Late Cretaceous Mongolia. It was one of the smallest ceratopsians, at about 2 feet long and 10-20 pounds–the size of a cat. Being so small and endothermic, I thought it could use a bit of warm fluff. I decided not to give it any tail quills (giving any and all ceratopsians quills has been a paleoart meme since the discovery of Psittacosaurus’s quills) for the same reason as mentioned above regarding Heterodontosaurus.

Above: a naked take on Gigantoraptor, a huge oviraptorosaur from Late Cretaceous China. It was one of the largest oviraptorosaurs (along with possibly Beibeilong), weighing between 2 and 3.6 tonnes full-grown. That puts it well over the Yutyrannus threshold (1.4 tonnes), so we should expect it to be at least partly naked, and possibly completely naked. That is one big plucked chicken. I gave it little filaments on the head, shoulders, and tip of the tail to improve heat dissipation like an elephant. Drawing a naked dino feels kind of weird, like it’s the 1970s or something.

Image credits:

Page image Fatbird T.rex Doswellia Euparkeria Teraterpeton Sordes Jeholopterus Shuvuuia Integument chart and Plateosaurus 1 Megafuzz blog post Yutyrannus Plateosaurus 2 Canada Therizinosaurus Naked Therizinosaurus Half-naked Therizinosaurus Scaly Irritator Fluffy Irritator Naked Heterodontosaurus Quilly Heterodontosaurus Fluffy Heterodontosaurus Feather Types