Cetaceans are a fascinating group of tetrapods that went from the sea to land and back again. Given the recent discovery of the new transitional protocetid, Aegicetus, I thought I’d give an overview of the crazy evolutionary journey whales have been through, and the niches they have stopped at along the way. With a couple pictures drawn by me!

Niche 1: Chevrotain Mimic

Cetaceans are artiodactyls, or even-toed ungulates. That means their closest relatives are the cloven-hoofed mammals, such as deer, pigs, sheep, and cows, as well as hippos. The earliest known whale-ancestor is a tiny hoofed creature called Indohyus, which lived 50-48 million years ago in what is now Pakistan. Though it looked sort of like a cross between a rat and a deer, it already had a couple key adaptations that suggested a partially aquatic lifestyle: particularly dense bones that provided ballast, and a whale-style inner ear that allowed accurate underwater hearing. Indohyus is hypothesized to have lived similarly to a modern-day chevrotain, foraging for food on land but hiding out underwater when threatened.

Niche 2: Mammalian Croc

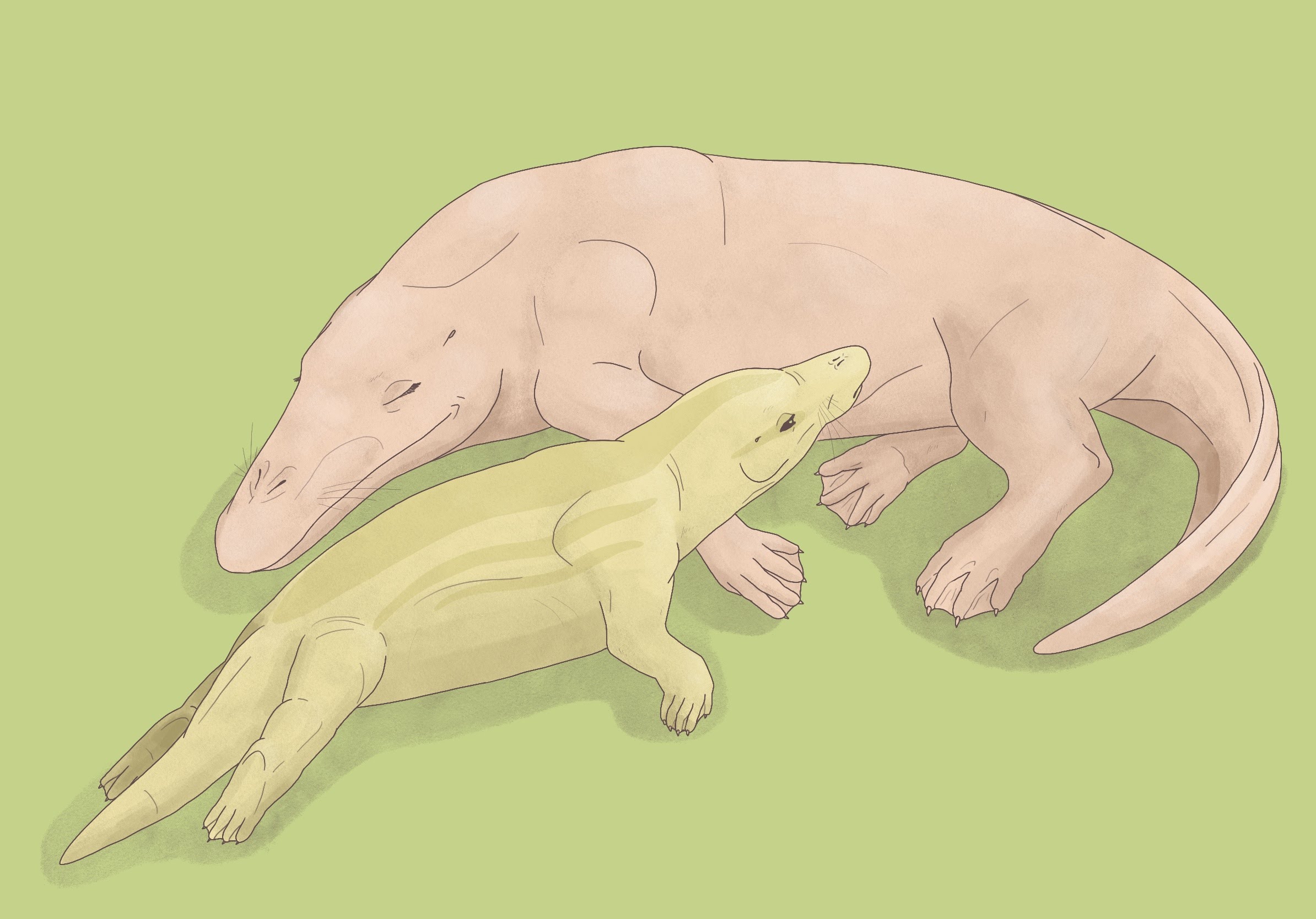

Just a couple million years later, Pakicetus appeared on the scene. This was another long-legged creature, but it had a couple important adaptations that distinguished it from Indohyus. Pakicetus’s fingers and toes were splayed and paddle-like, indicating that it probably spent more time in the water than the dainty-footed Indohyus. Pakicetus also had eyes more toward the top of its head, indicating that it may have hidden partially underwater while observing things above the water. Similarly to Indohyus, it had a whalelike inner ear. At this point in whale evolution, they appeared to be moving toward the niche that’s currently filled by modern crocodilians: semiaquatic ambush predator.

Above: Pakicetus, the croc whale.

Niche 3: Let’s Work On Swimming

Shortly thereafter (47.8-41.3 Ma), the dominant group of early whales became the ambulocetids, including Ambulocetus itself, meaning “walking whale.” This animal had a body plan much more specialized for swimming, with very short limbs and large hands and feet, and its eyes had moved back to the sides of its head rather than the top. It probably lived like a teleosaur–still an ambush predator, but trending more fully-aquatic.

Above: Ambulocetus, the teleosaur whale. By the way, this is what a teleosaur looked like:

Above: Machimosaurus, a very large teleosaur from Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous Europe.

Niche 4: Otters Before It Was Cool

By the middle of the Eocene (46-43 Ma), a new group of cetaceans had shown up, the remingtonocetids. These were streamlined foot-swimmers that probably lived like modern otters, hunting in the water but no slouch on land either.

Above: Kutchicetus, the otter whale. It was the smallest Eocene cetacean.

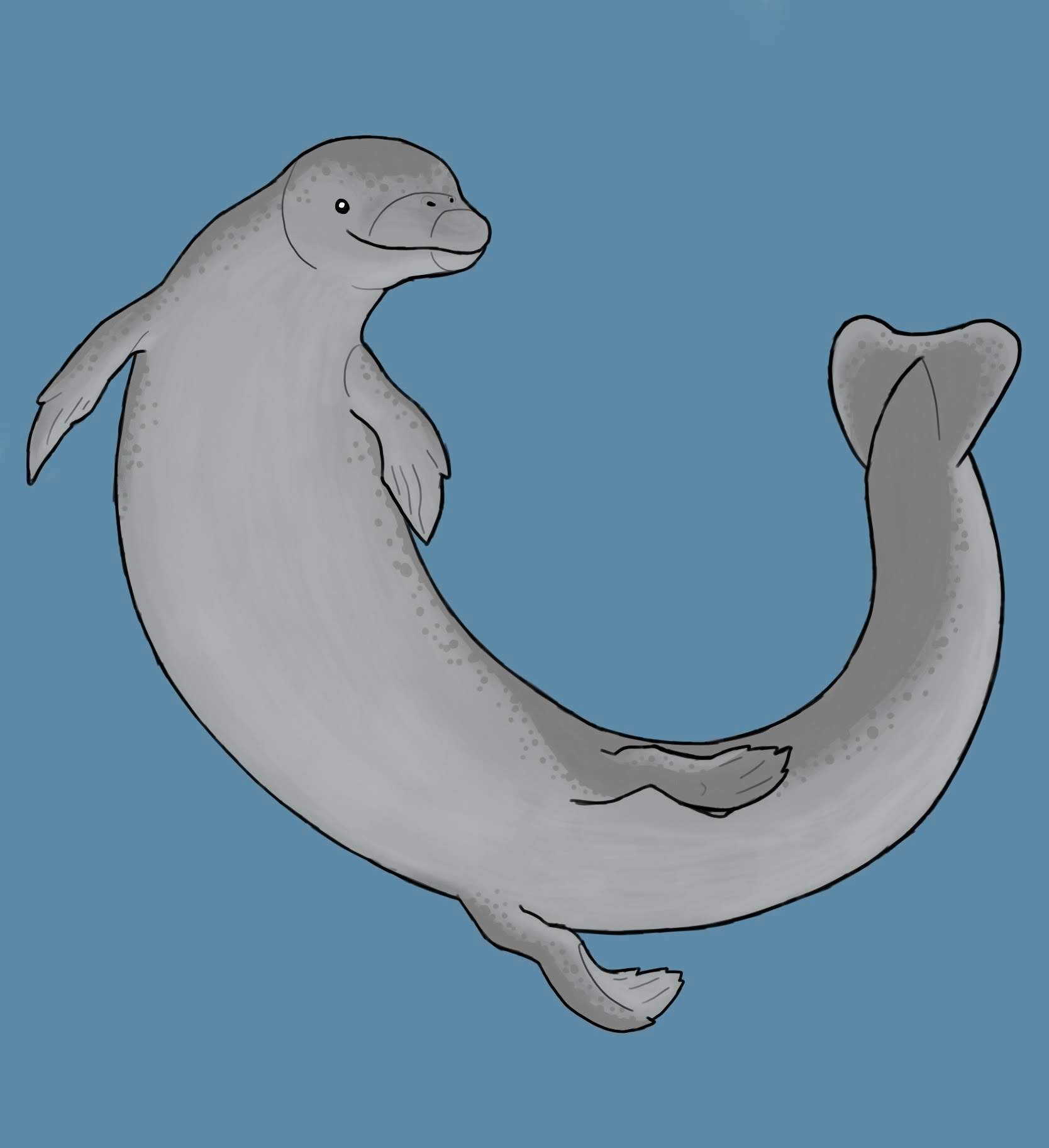

Niche 5: Seal Update

The next group to rise to prominence is called the protocetids, a very diverse group that covered a lot of time and a lot of different niches. One of the earliest is Rodhocetus, a powerful fully-aquatic foot-swimmer in the manner of seals.

Above: Rodhocetus, by me! For some reason, almost every existing depiction of Rodhocetus looks like a horribly ugly pig-like creature with duck feet and knobbly sticks for legs. I wanted to remedy this, so I made my Rodhocetus a lot more huggable.

Modern whales swim using their tails, and have extremely reduced hind legs. But up to this point, all primitive whales were foot swimmers. Getting from there to tail-swimming seems like it would require a transition in which the animals are temporarily less well-adapted, while their feet are being reduced and their tails are growing. This question had scientists stumped until just last year, when a new transitional protocetid was discovered, called Aegicetus.

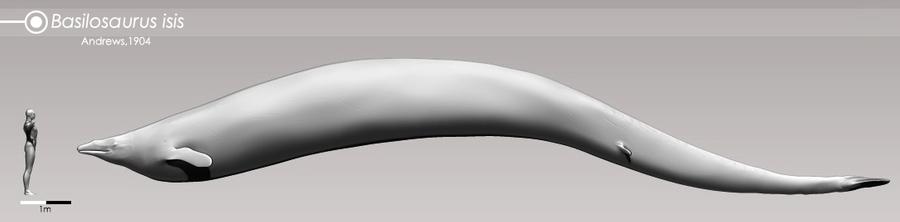

Niche 6: Eel Whale

Aegicetus was a very long whale with reduced, but still present, hind legs. It appeared to swim in an anguilliform fashion, like an eel turned ninety degrees. This explains how whales made the transition from foot to tail swimming: first, they started undulating their bodies to complement the foot propulsion, and then they became elongated to better undulate, and then their feet could be reduced without negatively affecting their swimming abilities. This also helps to explain why the famous early whale Basilosaurus (more on him in a bit) was so long–it had made the transition fully to tail swimming, but the long body was a hold over from the undulatory swimming strategy.

Above: Aegicetus, by me.

Longwhale

Now we’ve reached the Late Eocene, 41.3-33.9 million years ago, and the Basilosauridae have appeared on the scene. Basilosaurus itself was clearly recognizable as a whale by modern standards, and the whole process from Indohyus the tiny deerlike critter to a 20-meter-long behemoth only took 8 million years or so–a blink of an eye in geologic time.

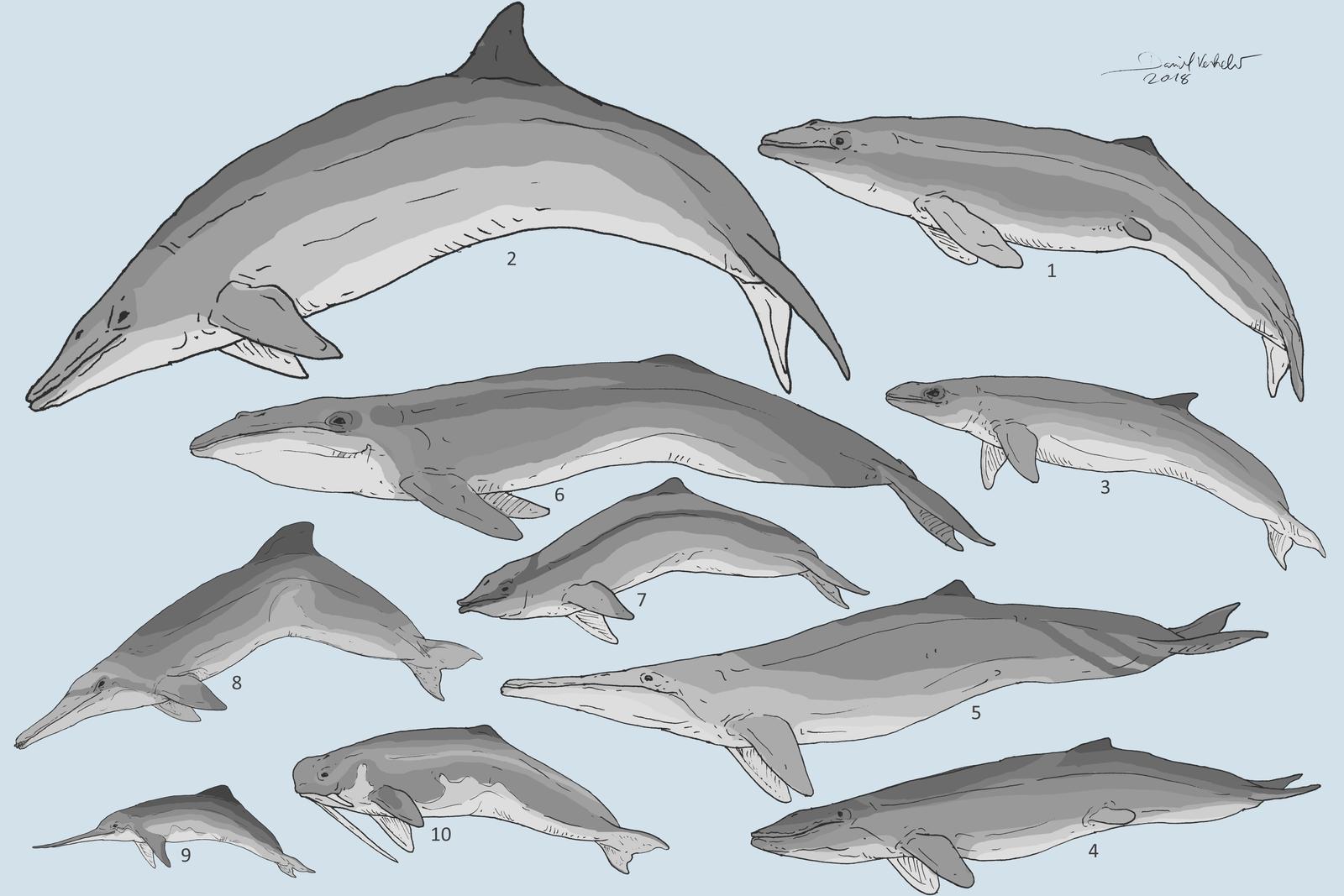

Whale Diversification

Once they’d developed the modern torpedo-shaped body plan, whales quickly diverged into many forms, separated into two main groups: Mysticeti, or baleen whales (“Mysticeti” means “moustache whales”), and Odontoceti, or toothed whales. Here is a collection of various extinct whales with representatives from both groups:

1-6: Mysticeti (baleen whales)

- Aetiocetus: transitioning from teeth to baleen in the Late Oligocene

- Llanocetus: part of the baleen family but lived in the Late Eocene, before baleen developed. Probably a suction feeder.

- Janjucetus: also part of the baleen family but still retained teeth, Late Oligocene

- Mystacodon: its head and jaw shape are more similar to modern baleen whales, Latest Eocene

- Tokarahia: Late Oligocene

- Cetotherium: a fully-functioning filter feeder, Miocene-Pliocene

7-10: Odontoceti (toothed whales)

- Simocetus: means “pug-nosed whale,” Oligocene

- Squalodon: an ancient relative of modern river dolphins, Oligocene-Miocene

- Eurhinodelphis: means “good nose dolphin,” the swordfish whale, Middle-Late Miocene

- Odobenocetops: the walrus-mimic whale, Late Miocene-Pliocene

Conclusion

Whales secondarily returned to the oceans very rapidly in the Eocene, traveling through a bunch of familiar semi- and fully-aquatic niches before arriving at the diverse forms we’re familiar with today. The fact that whales spent time looking like crocodiles, otters, and seals makes me speculate that if whales were to go extinct, would each of those groups become one level more aquatic in order to fill the empty niche?

Another thing to think about is the fact that we live alongside the largest animal ever, the blue whale, which weighs up to 177 tonnes–twice as heavy as the largest sauropods. Why were whales able to get so big just recently, while no aquatic creature could in the past? There are two factors that coincide with whales’ development of huge body sizes 3 or 4 million years ago. One is the current lack of giant aquatic predators. Sperm whales are the largest predators to ever live, but they don’t prey on other vertebrates, instead hunting giant squid in the deepest parts of the ocean; the last living predator a fully-grown whale needed to worry about was Megalodon, which went extinct 3.6 million years ago. This is right around when the truly giant whales appeared. Maybe being smaller and more nimble was helpful in avoiding super-predators, but once those disappeared, being large was helpful in warding off smaller threats.

The second factor is that 3 million years ago was the beginning of the most recent ice age (more technically known as the Quaternary glaciation), which increased the effects of seasonality on many global ecosystems. More seasonality means that certain food sources become overabundant in some seasons and unavailable in others, including the krill and other densely-schooling marine organisms many mysticetes depend on. Furthermore, seasonality also creates “blooms” of these creatures in different latitudes at different times of year. This means a large-bodied whale can (a) better exploit the overabundant food while it has access to it, (b) survive for longer periods without feeding, and (c) travel longer distances between seasonal food sources. These are all behaviors that we see are key to modern whales’ success.

Just for fun, here’s a list of the largest animals in various categories, from biggest to smallest.

| Category | Genus | Length (m) | Weight (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal | Blue whale | 29.9 | 177 |

| Predator | Sperm whale | 24 | 80 |

| Land animal | Patagotitan, Argentinosaurus, Alamosaurus | 39 | 50-100 |

| Cartilaginous fish | O. megalodon | 19 | 30-50 |

| Aquatic reptile | Shastasaurus | 21 | 30 |

| Non-tetrapod bony fish | Leedsichthys | 16.5 | 20 |

| Non-sauropod dinosaur | Shantungosaurus | 16.6 | 16 |

| Terrestrial mammal | Paraceratherium | 7.4 | 15-20 |

| Terrestrial predator | Tyrannosaurus, Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, Spinosaurus | 12-18 | 8-14 |

| Living terrestrial animal | African elephant | 4 | 6-10 |

| Living terrestrial predator | Saltwater crocodile | 6 | 1 |

| Terrestrial mammalian predator | Andrewsarchus | 3 | 1 |

Further exploration:

The page image is my drawing of Maiacetus, a protocetid from middle Eocene Pakistan whose name means “mother whale,” since the holotype was found with a fetus preserved inside. The fetus was positioned to be born headfirst, indicating that these animals still gave birth on land.

PBS Eons’s episode on whale evolution

The Common Descent Podcast’s episode on whale evolution