Family tree: Theropoda > Ceratosauria > Abelisauridae > Carnotaurinae > Majungasaurinae

Hometown: Madagascar, 70-66 million years ago (Late Cretaceous)

Discovered 1896, described 1955 (originally one of 50 species mistaken for Megalosaurus)

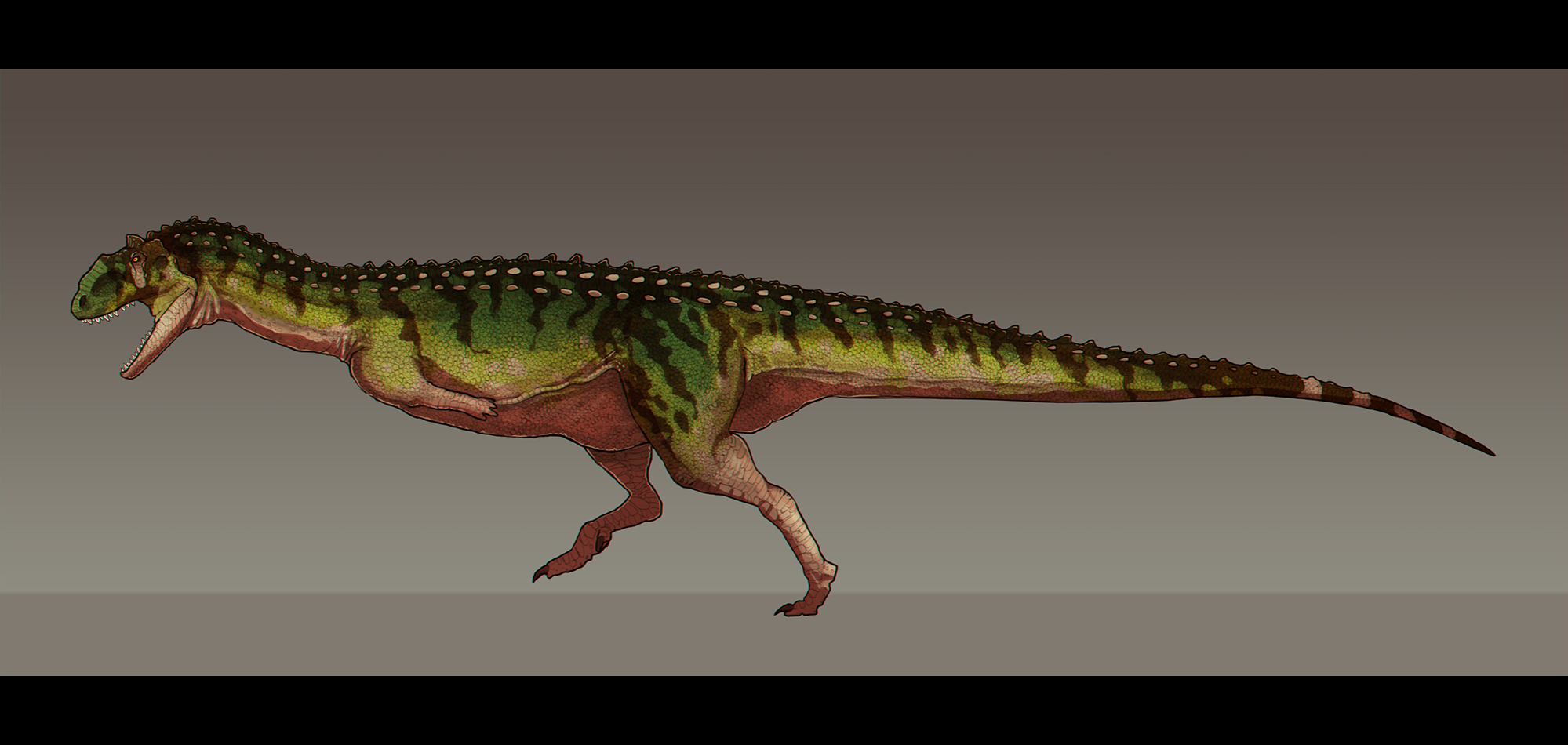

Majungasaurus was a Malagasy apex predator from the very latest Cretaceous, known from many specimens. Abelisaurs (pronounced “uh-BELLY-sores”) were a group of ceratosaurs that rose to prominence toward the end of the Cretaceous in the Southern Hemisphere. Prior to this, in the Early Cretaceous, the allosauroid carcharodontosaurs (including the famously large Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Carcharodontosaurus) held the apex predator role worldwide, but toward the end of that period they were displaced by tyrannosaurs in the north and abelisaurs in the south. While a fully grown Tyrannosaurus could reach 14 tonnes, most tyrannosaurs were more modestly sized, with Tarbosaurus weighing in at 5 tonnes, Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus at 2.5 tonnes, and Qianzhousaurus (Pinocchio rex) at a measly 0.75 tonnes. Abelisaurs as a group were more gracile, with the largest, Rajasaurus, tipping the scales at 3 tonnes, while the more famous Carnotaurus and our hero Majungasaurus weighed in the ballpark of 1.5 tonnes. The smaller Aucasaurus weighed only 0.7 tonnes.

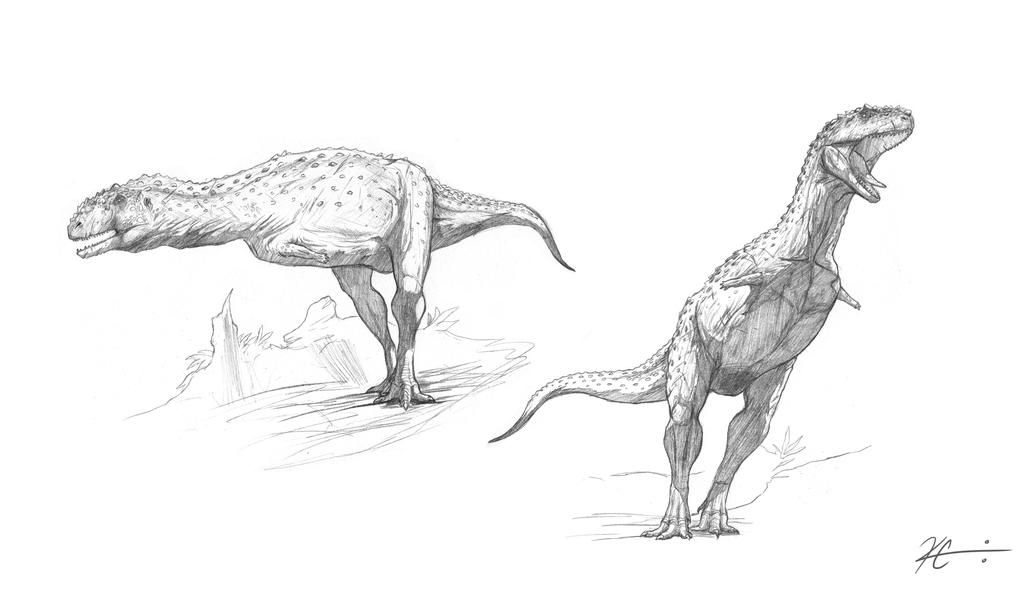

Abelisaurs had arms that made Tyrannosaurus look like a powerlifter. They had no elbow to speak of, and most had four little finger-stubs, at least three of which had no claw. However, their shoulders had a much more mobile ball joint than that of tyrannosaurs, meaning abelisaurs could stick their arms straight out to their sides if they wanted to. Some paleontologists and paleoartists have depicted these arms as being ornamented with protofeathery “pom poms” and used in mating displays.

Since Majungasaurus is known from a lot of skeletal material from multiple individuals, we can tell that there was very little, if any, sexual dimorphism, or physiological differences between males and females. Abelisaurs often had horns or other keratinous structures on their heads that look like they should be used for intraspecific competition and display; but species that do this, like deer or peacocks, tend to exhibit very noticeable dimorphism. Since Majungasaurus didn’t, perhaps their horns served another purpose.

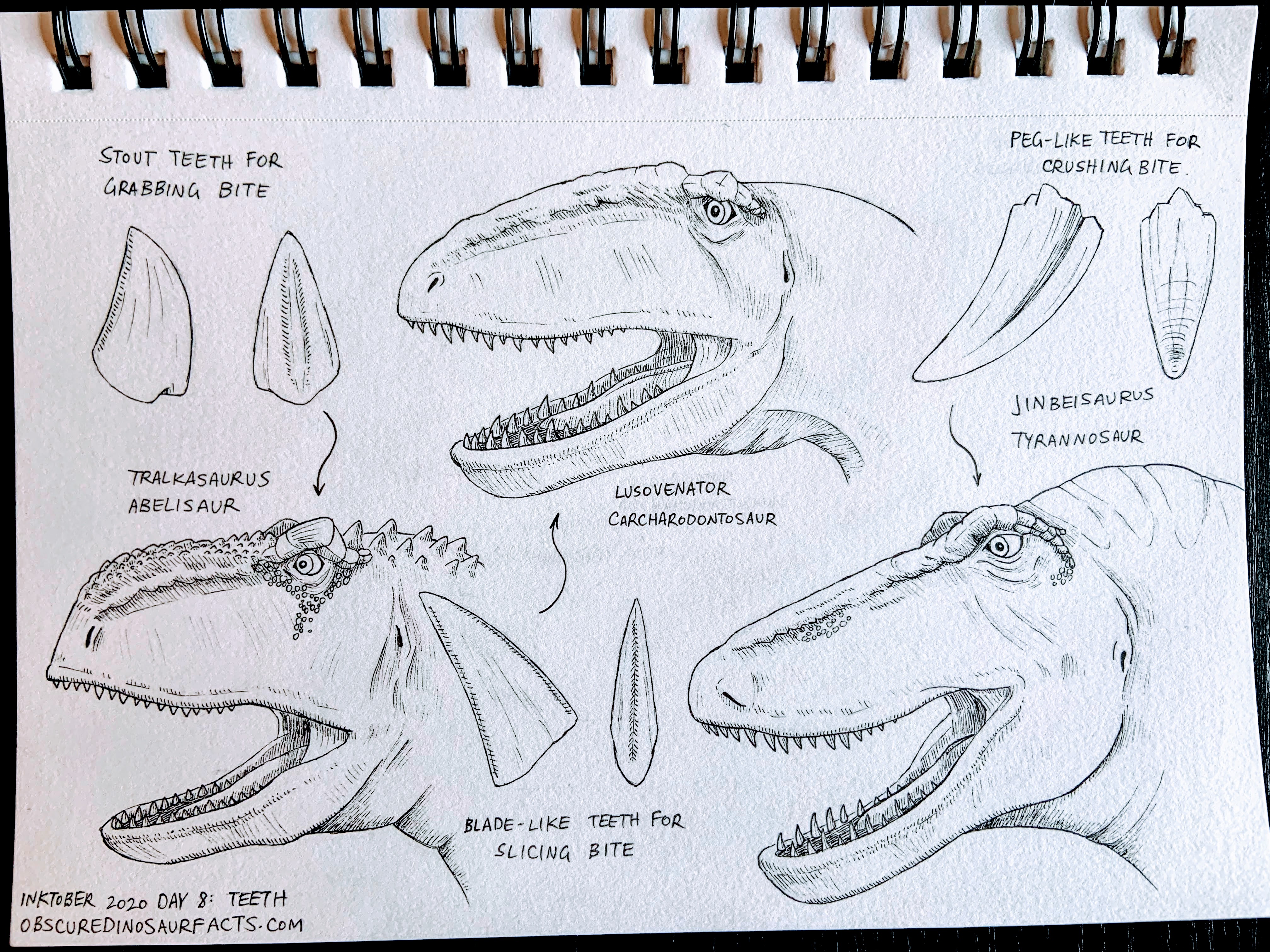

While allosauroids were the dogs of the Mesozoic, delivering many slicing bites or using the head like an axe to bring down prey, and tyrannosaurs were the bone-crushing hyenas, abelisaurs were the big cats, biting once and holding until the prey was subdued. This is shown through teeth adaptations (the tooth shape wasn’t as good at slicing), neck adaptations (bone shape and texture indicate huge neck muscles), and jaw adaptations (a short face is better at resisting torsion, while a long face is better at resisting vertical bite force).

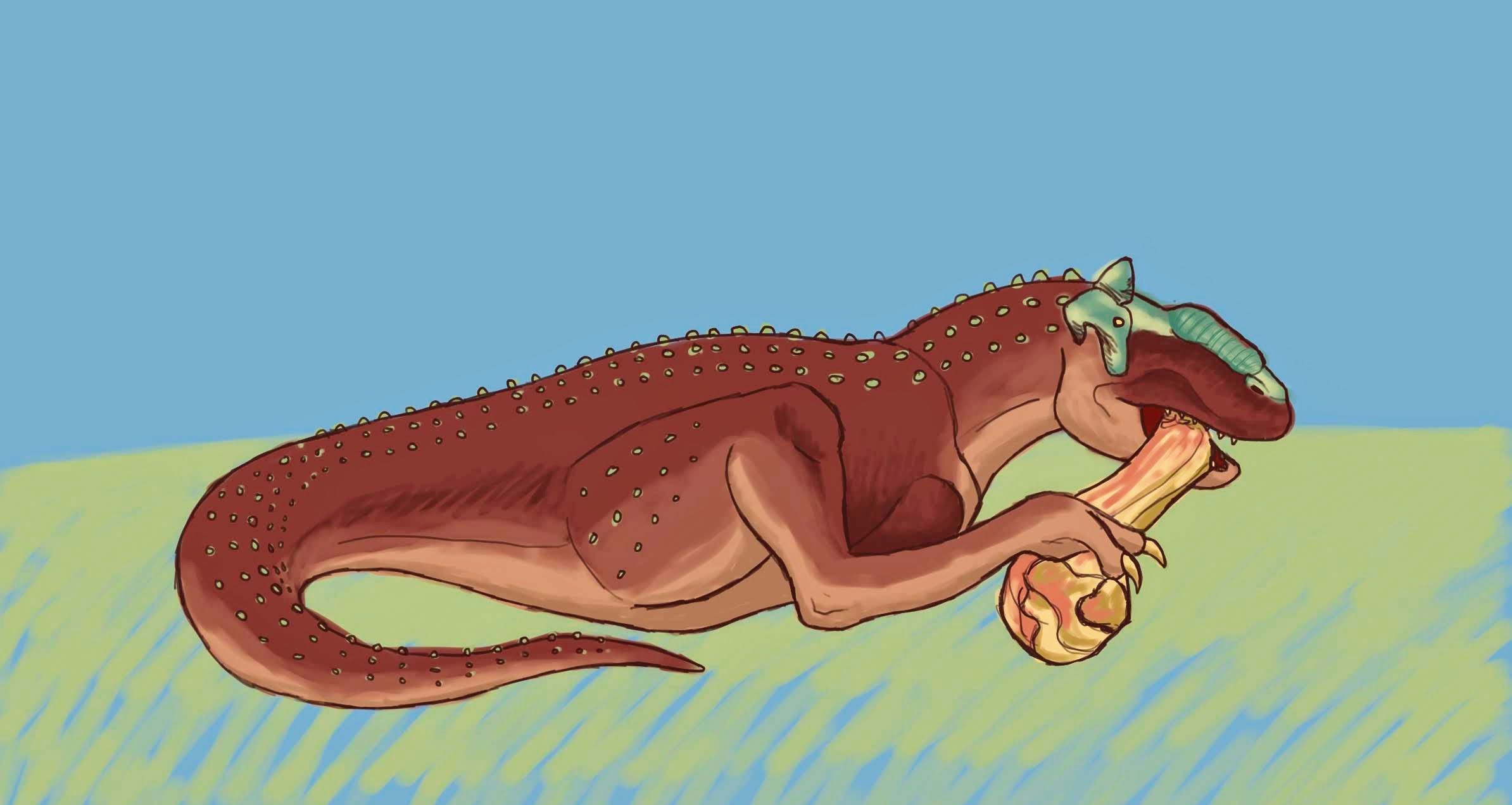

Majungasaurus is also the only non-avian theropod with direct evidence for cannibalism. (Update: we now have evidence of Allosaurus cannibalism as well!) Likely, they specialized in hunting sauropods like Rapetosaurus, but if they competed with another Majungasaurus over a carcass, they wouldn’t be opposed to eating that too. We also have evidence for the air sacs required for bird-style flow-through ventilation in Majungasaurus, indicating this evolved much more ancestrally than previously thought (since ceratosaurs are one of the theropod groups farthest from birds on the tree of life). Abelisaurs in general also took a very long time to reach maturity–20 years for Majungasaurus. Scientists can estimate growth rates (and other cool things like warm-bloodedness, ovulation cycles, and more) through bone histology, which is when they cut a thin slice of bone in cross-section and look at the growth rings under a microscope.

Majungasaurus was quite a bit longer-bodied and shorter-legged than other abelisaurs, creating a strangely-proportioned creature that looks almost like it should fall on its face. Recent research has found gnaw marks on Rapetosaurus bones matching Majungasaurus teeth. Imagine Majungasaurus gnawing on a bone–how would it hold the bone? With its legs? How do you think Majungasaurus stood up after lying down? Maybe it pushed itself up using its head.

(This is a quick sketch of one gnawing I did in 2019. The proportions are a bit wonky.)

Perhaps Majungasaurus’s short legs were better for taking down large-bodied prey like Rapetosaurus, a 15m (49 foot) long sauropod (lower center of mass, better able to deliver crippling leg blows), while Carnotaurus’s sprinter build allowed it to chase down faster, smaller prey.

Image credits: