This is a project I’ve been thinking about for a long time. There are lots of crows near where I live, and they are frighteningly smart and self-aware. They also are known to remember and hold opinions about individual humans, bringing trinkets as gifts to friends and calling other crows to help mob enemies. Given all this, is it possible to build a machine that can ingratiate me with the crow population while simultaneously making a little loose change? Enter the coin-operated crow feeder. It’s not a unique idea–there’s even a guy out there who sells kits for this specific purpose–but I wanted to design and build my own version, with a bit more functionality and flair than the kit version. In this post I’ll walk you through the design and build process so far. I’m not quite done yet, so this will be Part 1 of hopefully only three posts: Part 2 will be me finishing up the build, and Part 3 will be the crows’ reaction.

Design

First of all, what are the specs? I want a durable, weatherproof, crow-proof machine that will live out on my balcony, which crows will come visit with change they’ve picked up off the ground. The crow will put the coin in a hole and receive an amount or type of food proportional to the denomination of coin proffered. This goes beyond existing kits–they only take quarters, and only have one option for what and how much is being dispensed.

Since I’m a mechanical engineer, I was wondering at first if there would be a way to accomplish this entirely mechanically: that is, with no electronics. I came up with an idea of using a gravity-driven coin separator to drop a coin onto a lever, which would temporarily open a small spring-loaded door, behind which there would be a gravity-fed hopper of food, say peanuts. However, upon investigation this idea was pretty untenable, for a few reasons. The weight of a coin, especially a dime, is too small to reliably trip a mechanism, even when dropped from a great height. The mechanism was going to have to be very long and veeeery lightweight, as well as very low-friction. It also has the issue of the hopper doors getting stuck open if a peanut slid out wrong. So, I decided to pursue a powered system instead. This is really my first solo mechatronics project–I’ve done some robotics in college, but as part of a group and with a lot of setup help from TAs. Thankfully, I have a lot of people I can–and did–ask for help, including luthier (ukulele maker) Peter Hurney of Pohaku Ukuleles, who has lots of experience making all kinds of bizarre automata, and my fiancé, who is a software engineer.

Most people use Arduinos for projects like this–that’s a cheap, common little microcontroller that would have definitely been suitable for my application. However, my fiancé had bought a Raspberry Pi awhile back that he planned to use for something but ended up not, so this pretty high-end little computer was just sitting around, waiting to be used. It’s totally overkill in terms of computing ability for what I need, but it’ll do! Plus, it’ll make some things easier: I don’t need a separate motor controller board for my servos, since the Pi can pretend to be one.

Sorting the Coins

First, the coins will have to be sorted into denominations. To do that, I’m using a mechanical coin sorter, which is just a tilted ramp with differently sized holes in it. The tilt of the ramp causes coins to roll down one edge, and the smallest coins–dimes–will fall in the first hole while all others will roll on by, and so on.

To deal with the issue of crows putting trash, rocks, or other things into the hole that could clog the mechanism, I also added a pre-filter, basically just a slotted funnel, that will hopefully eject debris. It will also make the coins fall onto the sorter in a more repeatable fashion.

Sensing the Coins

Now that we have the coins dropping into separate areas, how are we going to let the computer know that a coin has been deposited? There are all kinds of sensors available, like optical forks, through beam sensors, break beam sensors, and more, but they all tend to be pretty expensive, and I’m not even sure that some of them could detect something as near, small, and fast as a coin (many of these are for motion detecting humans or wildlife at a distance). So instead, I’m making my own sensors out of laser pointers and photoresistors. Thankfully, this exact setup has Raspberry Pi official documentation, so I’ll have guidance.

A photoresistor is an electrical resistor whose resistance is high when it’s dark and low when it’s light. So the idea is I’m going to shine a laser pointer ($3 from Petco) onto the photoresistor, and when a coin falls and blocks the beam the resistance will suddenly change, telling the computer that a coin has been deposited. This circuit also requires a capacitor to work, but I won’t go into the details here.

Dispensing the Food

Finally, the last step. Once a coin has been deposited and the Pi knows it, it will turn the appropriate servo to dispense food from that hopper. Each servo is connected to a little Pac-Man-shaped dispenser, above which there’s a gravity-fed hopper. When the Pac-Man is facing away, the opening is blocked; when the Pac-Man faces the hopper, a little food can drop into his mouth. Then Pac-Man can turn and dispense the food down a ramp. At least, that’s the idea! We’ll see how this all works out in practice.

To make the coding easier, I’m going to try to have the machine queue any additional coins while it’s dispensing. That means if a crow inserts another coin before it’s gotten food for the first coin, the computer will finish dispensing the first batch of food before acting on the second.

The Pi has built-in Python capability, so that’s what I’ll be coding in. (It also has Scratch, but familiarity with Python looks better on a resume.)

In addition to the Pi and its peripherals, which cost around $100, I also bought $65 of servos, wires, and breadboards from Pololu, $25 of other electrical components, and $40 on food from Petco to stock it. (I was able to salvage some lumber from discarded crates at work, and I already had some hardware.) The crows will have to bring me a helluva lot of coins for it to pay for itself!

I ended up deciding on four types of food: peanuts (which I’d already had some luck tossing to crows that live near my house, so I know they like them), mealworms, cat food, and birdseed. For a penny they’ll get a bit of birdseed, for a nickel they’ll get a couple mealworms (ooh now that I think about it I hope they don’t get all mashed up in the dispenser), for a dime they’ll get a cat food pellet, and for a quarter they’ll get a handful of peanuts.

Integration

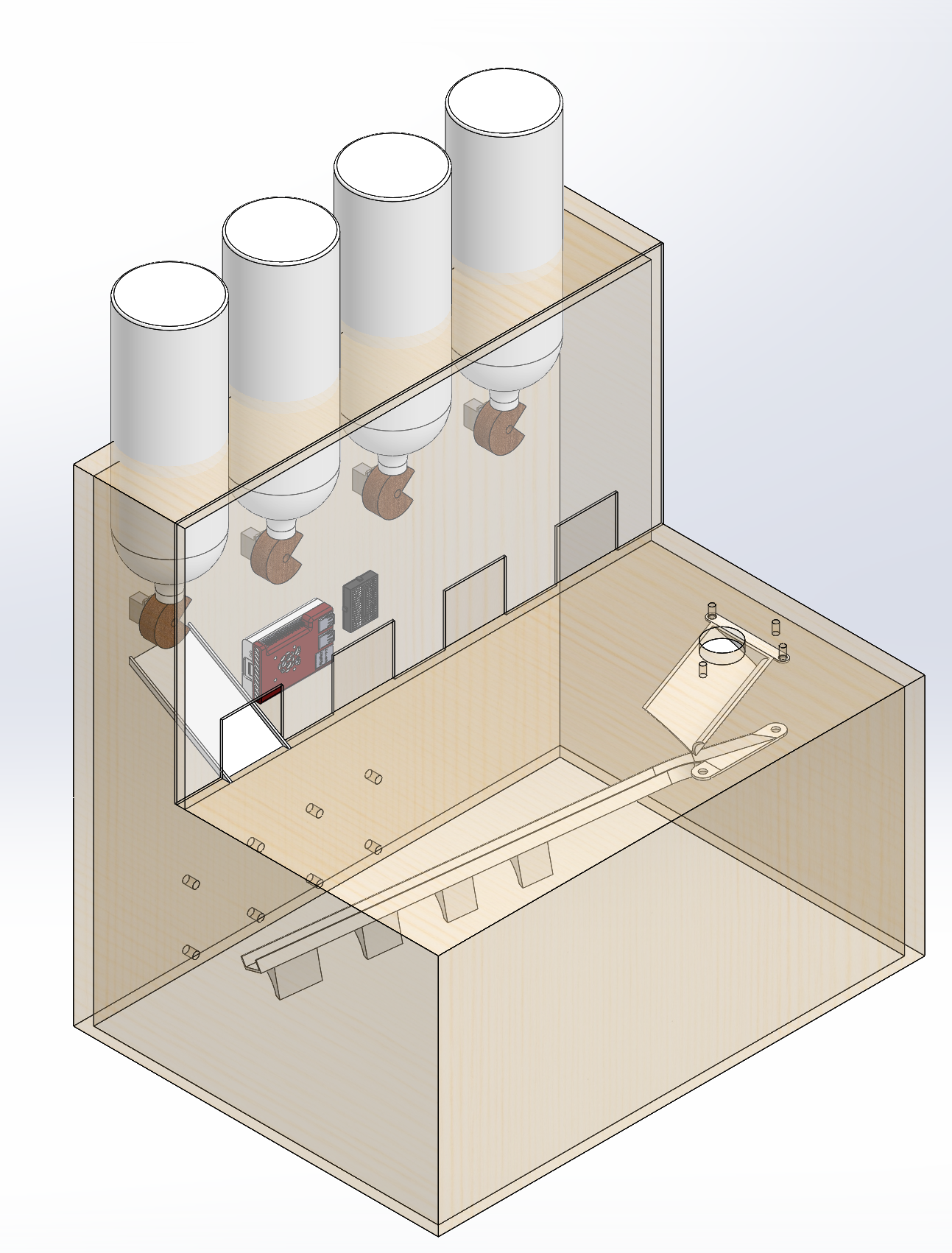

Here’s a hand-wavey model of how the whole thing will fit together:

The two-step shape is based on the existing feeder kits, but I plan to spruce it up a bit in real life with some paint and maybe some perches and other toys to make it appealing to the crows. Ignore the floating and missing parts; I was too lazy to model everything, and figured that since a lot of parts will be made by hand, it would be easier to just see how they end up and design around them.

Build

The first thing I did was get the Pi set up, which required finding a USB mouse, USB keyboard, and micro-HDMI cable. Thankfully, we had everything except the cable, which I ordered.

Next, I did a little research and ordered some servos, wires, and a breadboard from Pololu, a robotics supply company I ordered from in college. These type of jumper wires are standardized, and will connect to the Pi and to the servos. I got servos that have position feedback capability, which I’m not sure if I’ll need, but might as well have.

The next step was to get the servos moving using the Pi. This was pretty easy, since Pi documentation is great. After that, I got my laser tripwires working, which was also easy given the documentation. However, put them together and I got bunch of aberrant behavior: first, the servos started trying to break themselves (I figured out this was because the Pi and battery pack didn’t share a common ground, so the PWM signal the Pi was sending was interpreted by the servo as “always on, please break yourself”. I fixed it by grounding the Pi and the battery pack together), and then the Python code on the Pi kept spewing errors and warnings (this was due to mixing libraries: the one I needed for the lasers and the one I needed for the servos didn’t play nice together). But I got all that sorted out without too much trouble.

Next, I started building the internal components I’ll need out of chipboard, a kind of strong cardboard people use for building miniature houses and stuff.

Getting the mechanical coin sorter to work reliably required some “tuning” of the hole sizes and lengths, and slope of the ramp on both axes. I’m pretty sure it’s good now, but it’s a pretty touchy problem, especially telling the difference between dimes and pennies. It may stop working under, say, different humidity conditions. We’ll see.

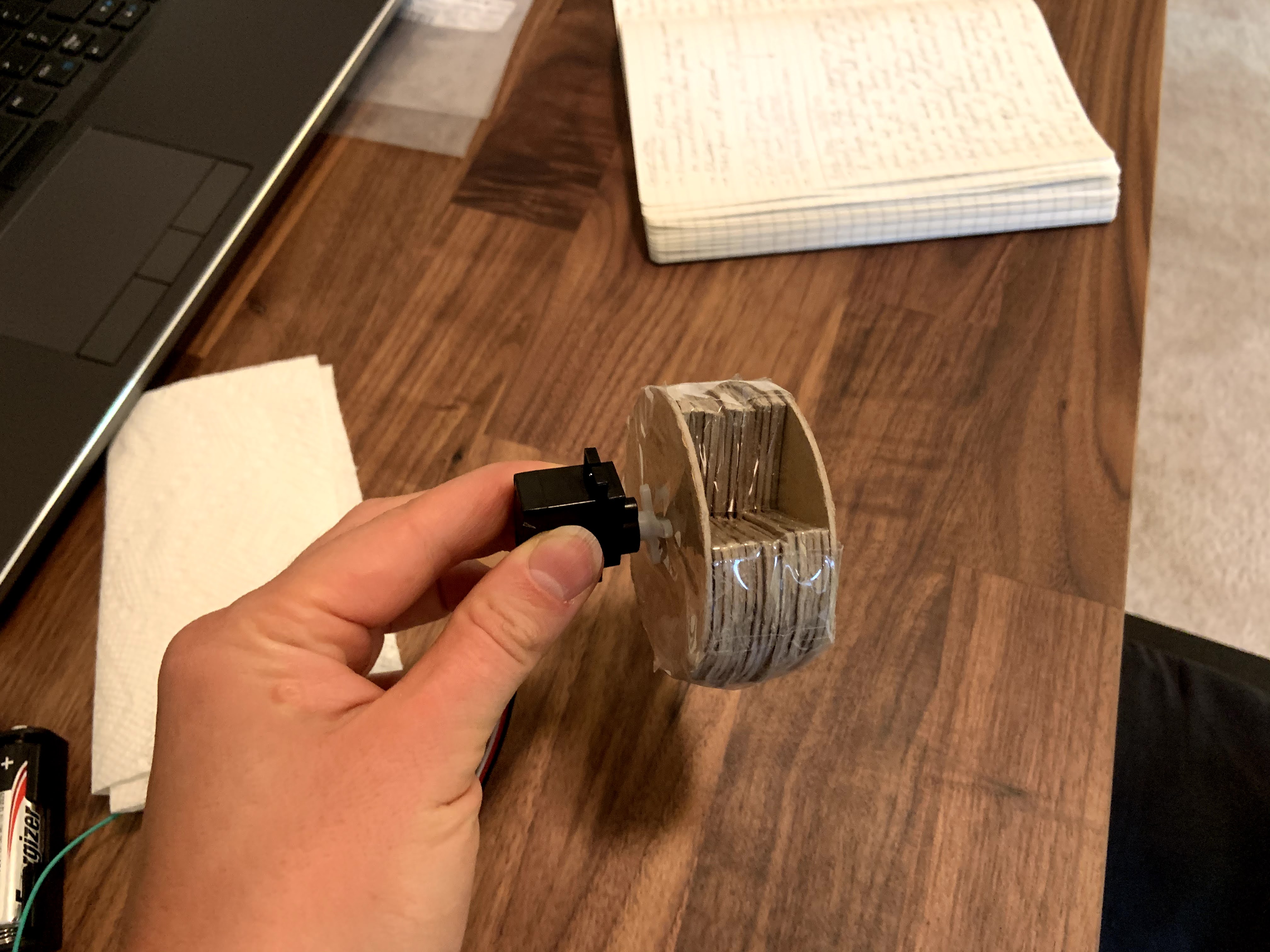

The dispensers are made of 14-16 layers of chipboard taped together. I almost gave myself a repetitive stress injury cutting all those circles.

This is one of those times when I really did not have the right tool for the job. I cut all these pieces using a miter saw and an old-fashioned hand saw. What I really needed was either a table saw or a jigsaw; using a hand saw caused the edges to be totally not straight. Oh well, I don’t think birds are known for their connoisseurship of carpentry!

That’s all I have for now. Stay tuned for the installation of the lasers and photoresistors, and the construction and painting of the box!