The world we inhabit and interact with on a daily basis, the world of megafauna, is far from the only world there is. At other size scales, there are layers upon layers of other worlds that we don’t notice, that operate by very different rules than what we are familiar with. In this post, we will explore the worlds of the very large and the very small, and the rules of physics that govern their workings. Strategies and body plans don’t just scale–what is a very good idea in a fish would be a very bad idea in a protozoan!

Overview: Fauna Sizes

First off, some terminology:

- Megafauna are animals approximately human-sized or larger, such as deer and bears.

- “Minifauna” are animals we routinely interact with that are smaller than humans, like dogs, mice, birds, etc. This term isn’t real, I just made it up because there’s no scientific term for everyday-sized animals.

- Macrofauna are small animals that usually live in soil or seawater, generally between 0.5 millimeters and a few centimeters in size. Terrestrial examples include earthworms, pillbugs, snails, and ants; marine examples include sponges, crustaceans, and bivalves.

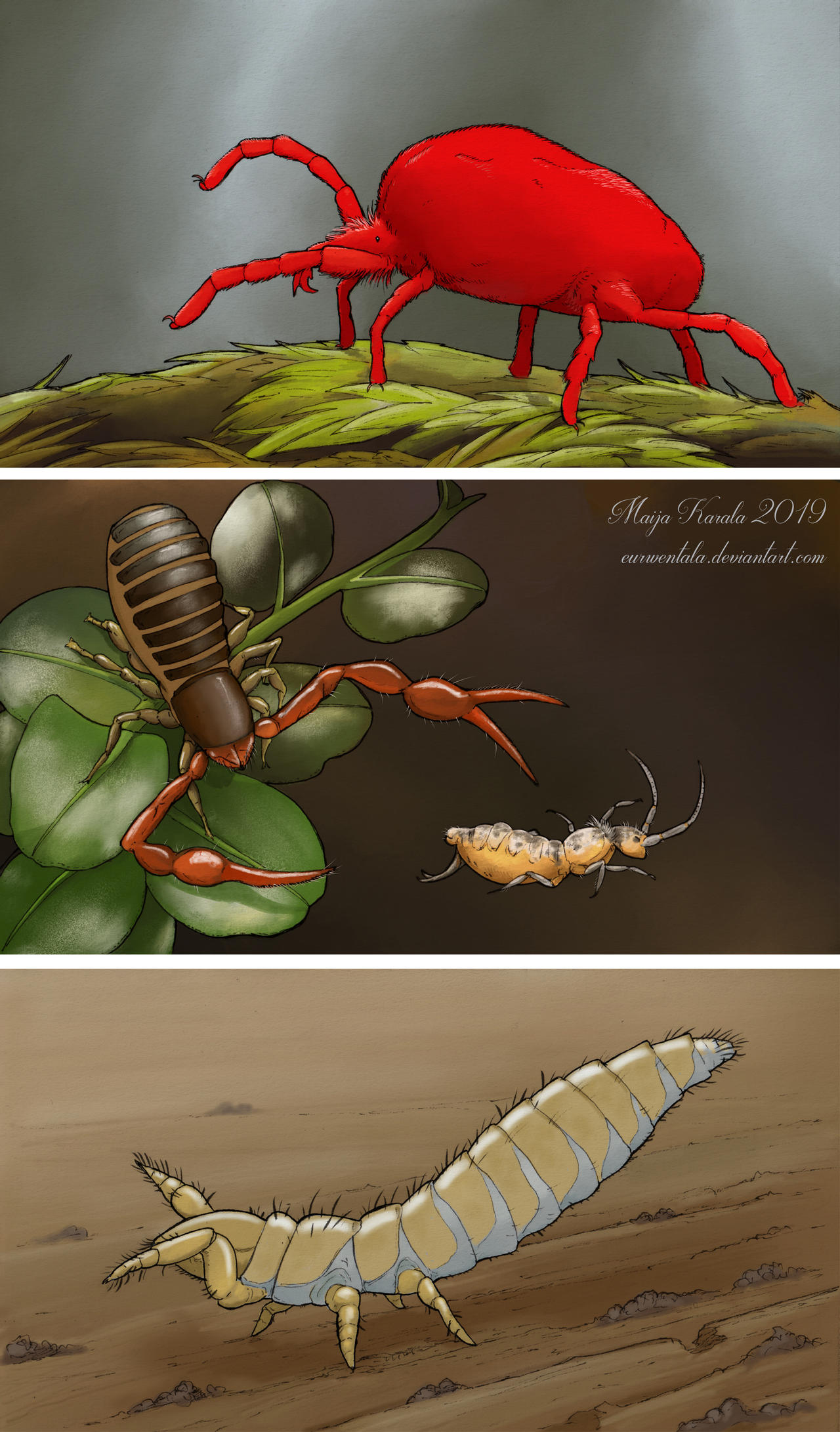

- Mesofauna (for terrestrial) and meiofauna (for marine) are very small animals just on the edge of visibility with the naked eye. Mesofauna are generally 0.1 to 2 millimeters across, and meiofauna are 0.045 to 1 millimeter across. (The difference is because of different sieving techniques used in soil versus marine sediments.) These are too small to move dirt particles around, so instead of digging or burrowing, they move around between grains. Some examples of mesofauna are springtails, coneheads, tiny spiders, tiny scorpions, potworms, and many other types of tiny arthropods; some examples of meiofauna are seed shrimp, pinworms, hairybacks, and many foraminifera.

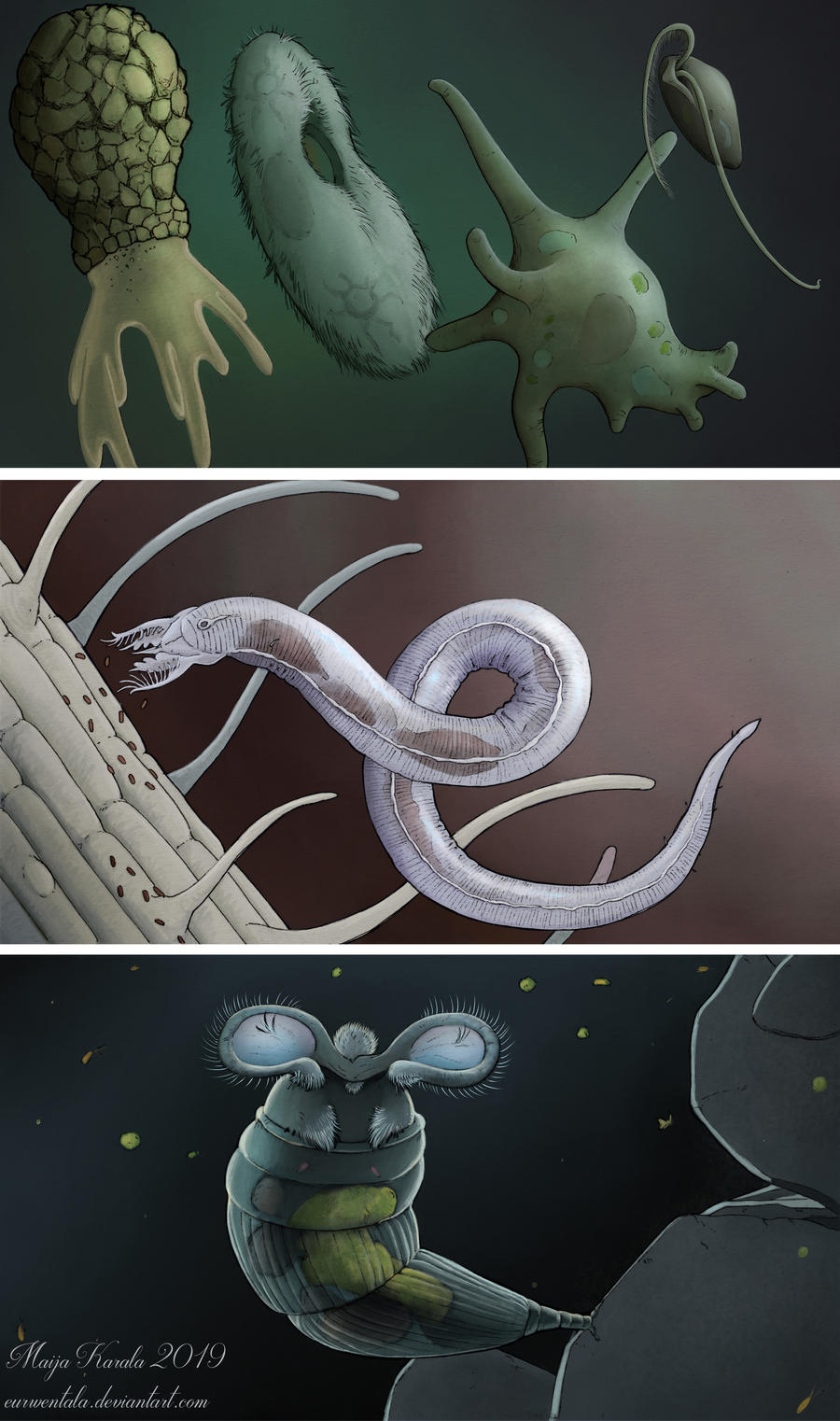

- Microfauna are tiny creatures too small to see with the naked eye, usually less than 0.1mm across. This is less than the width of a human hair. Examples include tardigrades (water bears), dust mites, copepods (small crustaceans), small nematodes, and rotifers.

- “Nanofauna” are the tiniest living things: prokaryotes, like the bacteria that make up your gut microbiome. These are commonly 0.001 to 0.01 millimeters long. Again, the name is in quotes because I made it up. Prokaryotes are single-celled organisms that don’t have a nucleus or other organelles, so their cells are much tinier and simpler than eukaryotic (complex) cells.

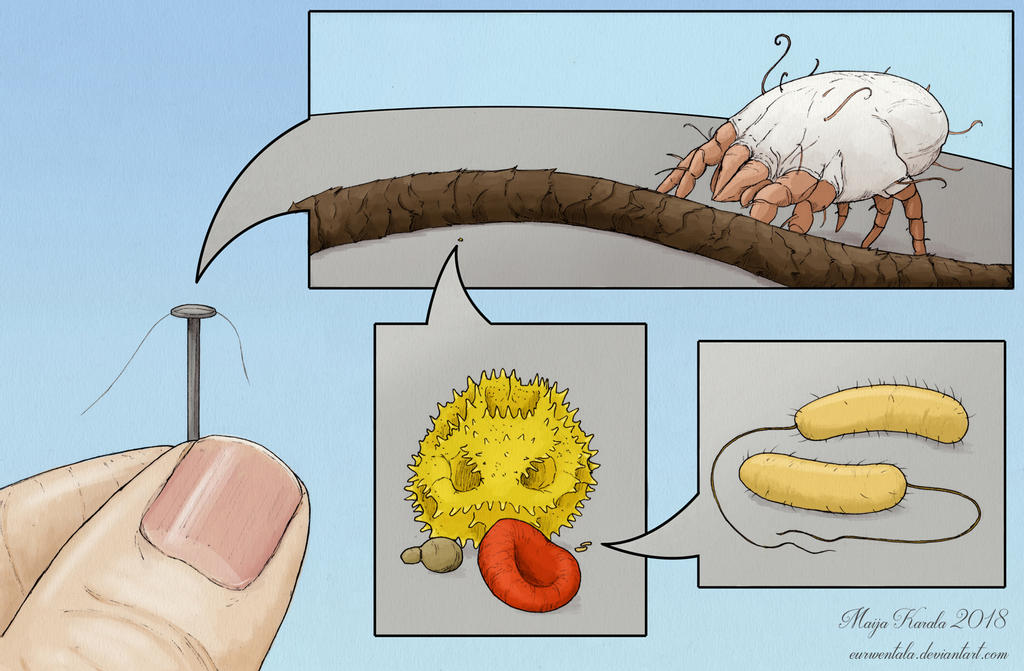

Here’s an image comparing the scales involved:

Really, each size class operates in a different world than the next. As an ant interacts with the world differently than a cat does, a mite has just as different an experience compared to that of an ant, and a tardigrade’s world is again, completely different.

(Fun fact: a human red blood cell is 0.005 millimeters across, while a human capillary is only 0.002 millimeters across. That means red blood cells not only have to go single-file to reach these areas, but they have to squish themselves down in order to fit! Seems like a poor design choice to me.)

How Lilliputians Swim: The Reynolds Number

This will seem like a total left turn, but bear with me for a minute and we’ll get back to biology. The Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity that’s important in fluid dynamics. It’s defined as

\[Re=\frac{ρuD}{μ}\]Where ρ is the fluid’s density (for example, oil is less dense than water, which is why a layer of oil can float on water), u is the fluid’s speed, D is a length we care about (for our purposes, just think of it as the scale we’re operating on), and μ is the fluid’s viscosity (for example, honey is more viscous than water, which is why it flows slowly and regularly).

When the Reynolds number is high, the fluid flows turbulently, all swirly vortices and chaos; when the Reynolds number is low, it flows laminarly, or smoothly. When the Reynolds number is really low, the fluid acts more like Jell-O. This makes sense if you think about it in terms of the components that make up the Reynolds number. It scales proportional to density (if a fluid is heavy, it flows more turbulently–think mercury, which scatters into droplets more readily than water); proportional to speed (if a fluid is going faster it’s more likely to get turbulent–think of how the steady flow of a garden hose turned on low can become a wild spray when the valve is opened completely); proportional to scale length (imagine water falling through a straw versus a large-diameter pipe); and inversely proportional to viscosity (even though honey is denser than water, its high viscosity means it flows more laminarly).

What does this have to do with all the sizes of animals I went through above? Well, when D is really small, as is the case for microfauna, the Reynolds number goes really low, even for water. So for really small animals, living in water is more like living in Jell-O, and their swimming strategies reflect that difference.

For fish, there are three main methods of locomotion: anguilliform, carangiform, and thunniform swimming. Anguilliform is how eels swim, by undulating the entire body. Thunniform is how tunas, sharks, and sailfish swim, by moving just the tail back and forth and holding the body stiff. Carangiform is how most fish swim, and is kind of a hybrid between the two. For fish, who move in high Reynolds number circumstances, thunniform is by far the fastest and most efficient way to get around. Anguilliform is more maneuverable, which is why eels live in the tight spaces of coral reefs, rather than in the open ocean (eels can even drive in reverse).

However, for microfauna, thunniform swimming is completely impossible. In low Reynolds number situations, any action that looks the same played backward in time will get you nowhere! Take, for example, a scallop, which swims surprisingly effectively by opening and closing its shell in its high Reynolds number environment:

However, if you were to simply scale the scallop down to microfauna size, the distance achieved by opening its shell would just be reversed by closing it. It wouldn’t be able to get anywhere at all! Scientifically, it’s known as a “nonswimmer”. Similarly, thunniform swimming is a nonstarter in low Reynolds number environments. If you played a video of a shark or scallop swimming against a blank background in reverse, it would look the same as played forward. The reason this heuristic works is because in high Reynolds number environments, when you push a fluid, say, with your fin, it moves out of the way in a vortexy, turbulent fashion that’s different from the way that it moves when you pull it. Furthermore, you can achieve unequal forces by moving fast versus slow through the fluid–this is how the scallop moves forward even though its shells are rigid, by moving fast on the power stroke and slow on the reset stroke. In low Reynolds number environments, any fluid you move out of the way in one motion, will just return in the exact same way when you do the opposite motion, regardless of your speed, undoing any distance you’ve achieved.

However, an eel isn’t the same when played in reverse–the wave travels along the eel’s body in the opposite direction of the way it’s moving. This is also why it’s able to swim backward. That means an eel scaled down would be able to make it in the microfaunal world. And that’s why so many microscopic organisms use variants of this anguilliform “wave” strategy to get around.

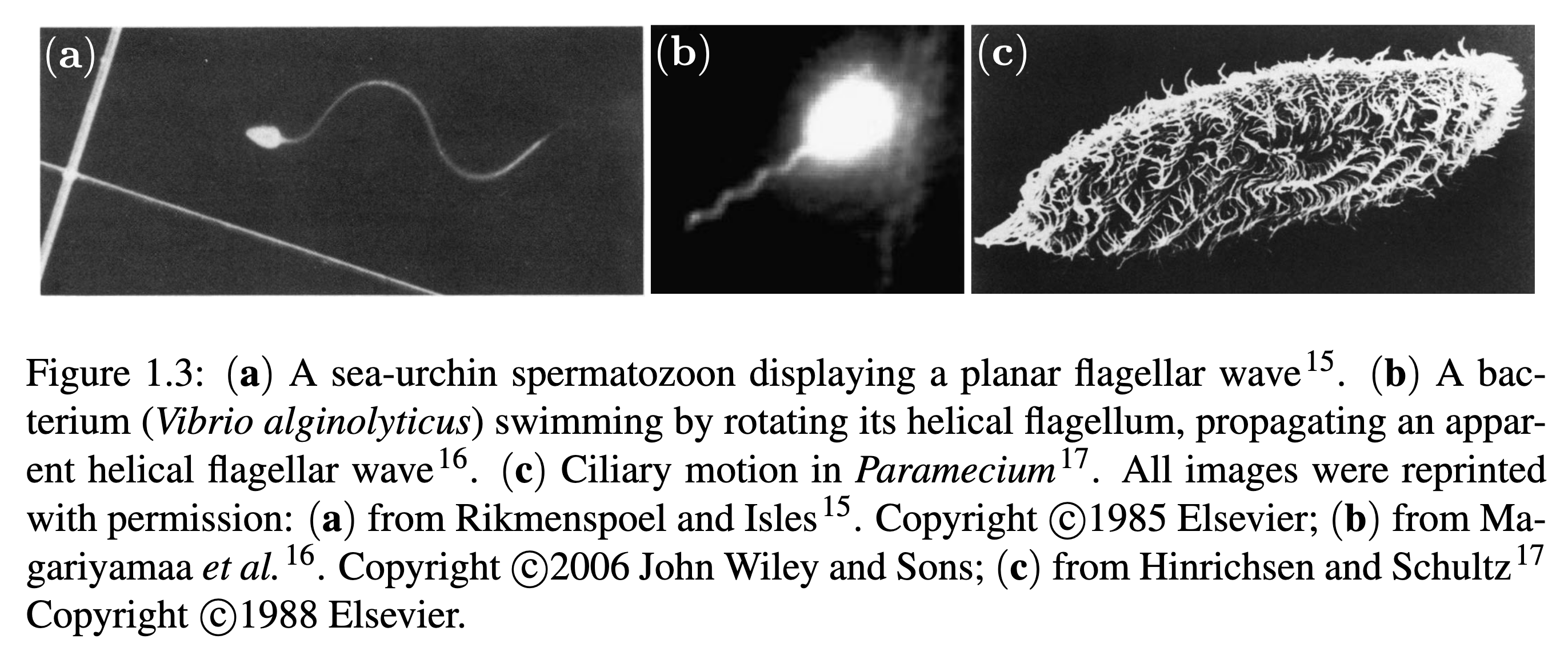

There are three main ways to do this: with a planar flagellum, like an eel or a sperm cell; with a helical flagellum, kind of like a propeller; and with an array of cilia (singular: cilium), or tiny hairs all over the outside of the creature that beat in a pattern like a stadium doing the “wave”.

However, there’s one microfaunal animal that just does things its own way: the tardigrade, or water bear. It doesn’t care that the Reynolds number of its environment is way too low for legs to be effective–it just tries that much harder!

Here’s a tardigrade encountering a Paramecium, a protozoan that moves using cilia. The Paramecium is so nimble and quick compared to the tardigrade! Also note, a Paramecium is composed of a single, giant cell, while a tardigrade has many thousands of cells. The huge range of cell sizes is mind boggling!

(Note: Actually, tardigrades are accomplished walkers, and avoid swimming when they can. They’re not maladapted; they’re just not suited to the environment created when we put them on a glass slide to observe them!)

Also, here’s a video of a tardigrade doing a big poo for those interested.

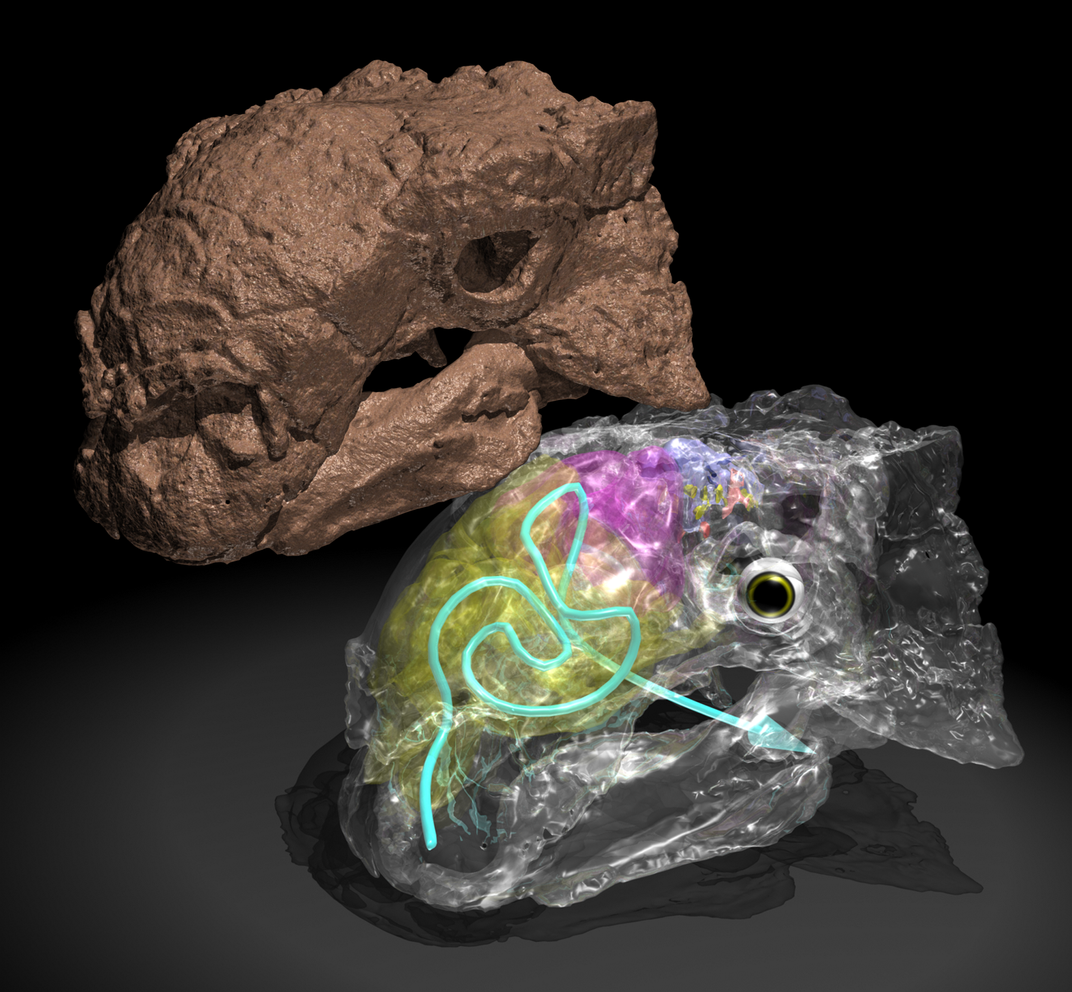

Aside: Mold Pigs

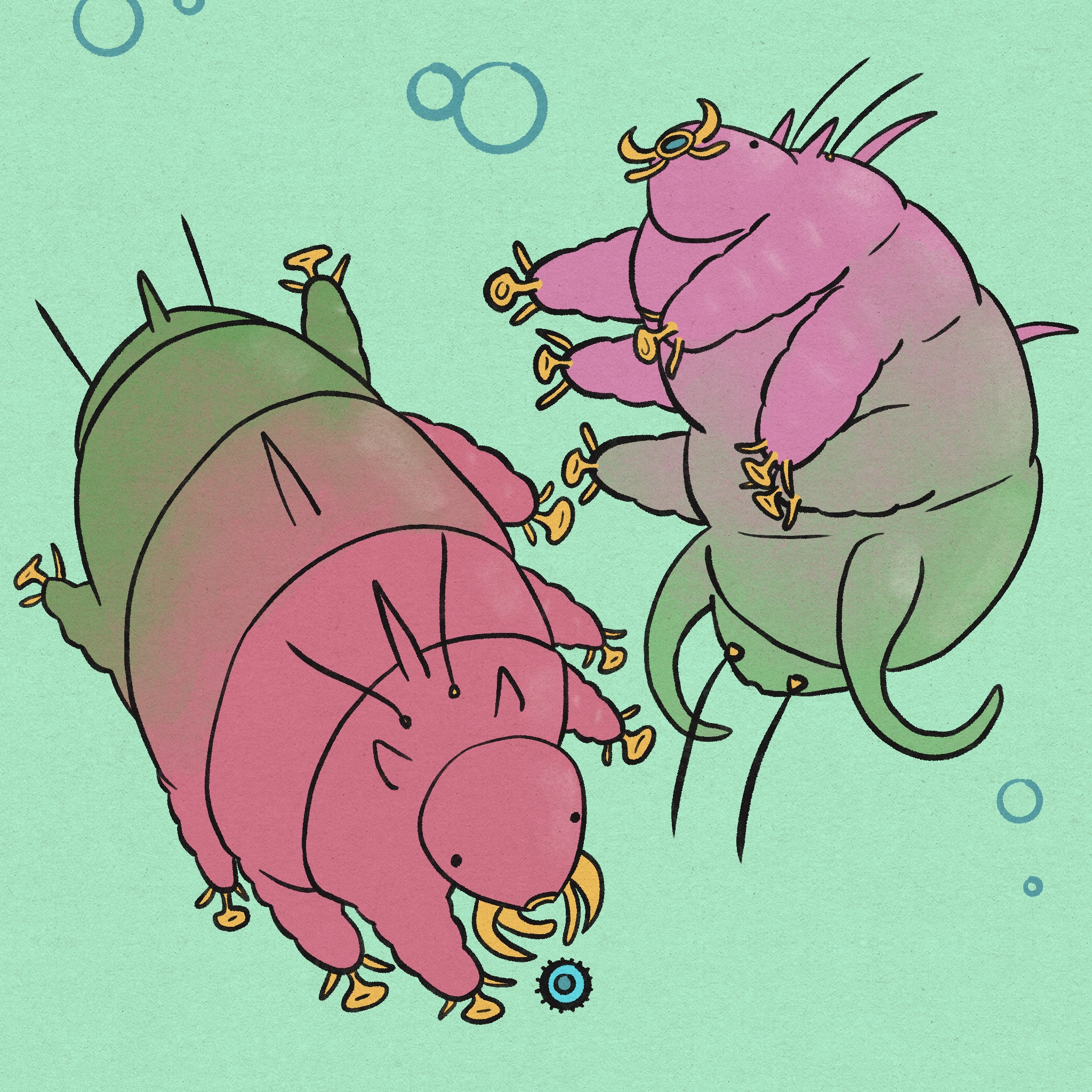

Just last year, a piece of Dominican amber was described that contained hundreds of specimens of a tardigrade-like creature, dubbed “mold pigs” (scientific name Sialomorpha dominicana), which ended up being not only a new genus and species, but a whole new family. While tardigrades have mouths for sucking and claws at the ends of their feet, mold pigs had mouths for biting and sticky discs at the ends of their feet. While tardigrades have vestigial eyespots on the surface of their brains (???), mold pigs have the more normal arrangement of external eyespots. You know, for seeing. They also seem to have been hermaphroditic and gave live birth to six-legged babies, and a few specimens have their hind legs modified into weird hooks for an unknown reason. They lived somewhere between 20 and 45 million years ago and are presumed extinct, but since so little of the microfaunal biota is characterized, there may be living descendants out there somewhere. I love how we know so much about these tiny, ancient animals! These are what is depicted in the page image at the top of this post.

How Giants Move: The Square-Cube Law

I’ve discussed this in my other post about miscellaneous paleontology concepts, and the impact it has on thermoregulation and proportional strength, so if you want a bit more detail, check that one out. However, I’ll go over it quickly here as well.

The square-cube law states that as an object increases in overall dimensions, its volume increases faster than its surface area. That means properties that depend on volume, such as weight and heat generation, scale differently than properties that depend on area, such as strength and heat dissipation. This is the main physical reason that large animals have different body plans than small ones, and why insects and other small animals can lift objects many times their weight, jump many times their length, and survive long falls: they have proportionally more strength and less mass. However, invertebrates also have another advantage that lends them their prodigious strength: the protein resilin. We mere vertebrates use elastin in our connective tissue, which is half as strong, half as tough, and 25% less extensible than resilin. Resilin is also very efficient, losing minimal energy as heat when extending and retracting, which is especially important for flying insects, some of which beat their wings over a thousand times a second. A creature attempting this using elastin would probably cause themselves to fatally overheat.

On the other end of the spectrum, giant animals need special adaptations to support their massive weight and to shed sufficient heat. Large modern animals like elephants, hippos, and rhinos, and large extinct animals like sauropods and indricotheres, had columnar legs (in which all the joints are vertically stacked on top of each other) with near-circular feet (for spreading the weight evenly over the foot area). I’m not really into Game of Thrones, but they did get this right with their giants: they have elephant-like feet that look a bit funny on a humanoid. (Trey the Explainer has a great episode on this.)

In terms of thermoregulation, large animals can exhibit what is called gigantothermy: even if they have a slow metabolism that only generates a tiny amount of heat per unit mass, they just have so much mass that they effectively are warm-blooded anyway. And in reality, most large animals have or seem to have had metabolisms far above that threshold, and thus require special mechanisms to shed the excess heat.

Large dinosaurs employed a variety of strategies to keep cool. Tyrannosaurs had bundles of blood vessels near the tops of their heads that could expand while the animal was resting in the shade to aid heat loss, and contract while in direct sunlight to avoid taking in too much heat; ceratosaurs (Carnotaurus and relatives) had similar blood vessels, but in the nose area. Ankylosaurs (the armored ones) had “crazy straw”-shaped nasal passages in order to transfer as much heat as possible into their breath, and sauropods (the long-necked ones) had air sacs throughout their bodies that would have worked in a similar fashion.

For large mammals like elephants, their sparse hair actually helps them shed heat, by acting like radiator fins. If you were wondering about your bald or balding friends, hair sparser than 30 per square centimeter helps to shed heat, rather than retain it. (The average, non-balding human has 200 hairs per square centimeter.)

Even with all these tricks, large animals just aren’t able to muster the same proportional strength and speed as small ones. This is why you may have seen headlines in the past like “T. rex couldn’t run” or “Sauropods: too big to walk?”. The details are still being debated, but the scientific consensus is that the largest dinosaurs could definitely walk, but not much more than that: large sauropods, despite having legs two or three times the height of a human, would have walked at only 6 or 7 kilometers per hour (around 4 miles per hour). You would have been able to comfortably keep pace next to one! An adult Tyrannosaurus would have had a top speed of only 27 kilometers per hour (17 miles per hour), but had a very efficient gait due to its long strides: a champion long-distance jogger. (A juvenile Tyrannosaurus could’ve hit a blistering 53 kilometers per hour (33 miles per hour), so if you somehow ended up back in the Cretaceous, you’d better hope you encountered Sue rather than Jane!) Here’s a fun article comparing various dinosaurs’ top speeds, and the general relationship between speed and size.

Conclusions

What is it like to be a mold pig? A giant sauropod? Understanding the physical rules and limitations creatures different than us experience is the first step to getting into their shoes. Whether you’re designing speculatively evolved or fantasy creatures, critiquing kaiju or humongous mecha films, or if you’re just interested in the worlds that operate on scales we can’t percieve, I hope this post has been interesting and informative. It sure was interesting for me to research–some of this stuff takes me back to my mechanical engineering classes in college!

Also, True Facts has a great new video with a lot more info on how tardigrades eat, reproduce, and survive extreme conditions. I’d highly recommend it if you have ten minutes.

Credits and References

The first four pictures in this post are by renowned paleoartist and scientific illustrator Maija Karala.