ix. Uriel, Part 3

This is a continuation of one of the stories in my previous two creative writing posts. If you haven’t read those (or forgot what happened), I’d recommend going back to read Part 1 and Part 2 and Ctrl-F’ing for “Uriel” before continuing. I’ve written a lot more than this and plan to attempt to publish it, but here’s a blog-post-length sneak peek.

III. T+3.12 years

“Sir, I have a surprise for you,” said Uriel.

I raised my eyebrows. “Oh yeah?” The last time Uriel had surprised me had been about a year ago, when he’d revealed the second pasture and brought in Paola. I wondered if it was possible for this surprise to be equally life-changing.

“Please go to your quarters. You will see that a new area is available.”

Paola and I quickly got up from where we’d been sitting in the grass and ran into my quarters, which we hadn’t been using very much since I moved my bed into hers. It took me a second to spot the change. In one corner, a floor panel had slid aside, revealing a ladder going down. The last time Uriel opened a new section of the ship, I had checked all the other walls for similar hidden doors, but I hadn’t thought to check the floor.

“Uriel! What’s down there?” Paola demanded.

“A medical bay, a swimming pool, and much more,” Uriel said. “I suggest you go and see.”

I smiled and shrugged at Paola, who still looked a bit apprehensive, and headed down the ladder. I guessed I had more faith in Uriel’s goodness than she did. Then again, she wasn’t the one he was explicitly looking out for.

I descended about thirty feet, arriving, as promised, at the short edge of a swimming pool. I heard Paola scrambling down behind me. On one side of the pool was a closed door labeled MEDICAL, and on the side farthest from us was an open set of double doors that appeared to lead “outside”. Paola came up beside me and we exchanged a glance, then started walking toward the double doors together.

My heart was pounding with excitement as the scene came into view. It was a forest. There were quite a few different types of trees–redwood, birch, chestnut, and peach trees were all visible from where I was standing, and berry bushes and hazelnut shrubs grew in between. Nettles, wild garlic, and mushrooms poked plentifully out of the leaf litter. None of the trees were very large, with the tallest reaching only halfway to the high ceiling, but they all looked healthy, and some were supported by plastic rods. The air smelled mulchy and sweet, and I heard what sounded like a turkey gobble in the distance.

Paola noticed the rods too, and pointed at one. She whispered sharply, “John. Do you think there’s someone else in here?”

I was about to say something when Uriel interrupted. “Yes, Paola. They are on their way to you now. I think you will like them a lot.”

They! More than one new person? That would be at least tripling the number of people I’d seen in the past three years. Paola took my hand and gripped it. I squeezed back, then put my arm around her shoulder in a side-hug and patted her reassuringly. I murmured, “The last time something like this happened, he wasn’t wrong.” She looked up at me and smiled briefly, then resumed looking around restlessly. The turkey gobbled again. A strange sound to encounter on a spaceship, one might think, but I wasn’t surprised by anything Uriel cooked up at this point.

Finally, I heard crunching footsteps approaching. Between the trees, I could see two people approaching, also holding hands. They were an older Asian couple, wearing lumberjack-like flannel and denim. They were smiling brightly at us and didn’t seem nervous at all.

“It’s great to finally meet you, John and Paola,” said the woman. “I’m Valerie. This is Dave.” We all shook hands. “Welcome to our neck of the woods.”

“Nice to meet you too,” I said. “I’m sorry, but it seems like you know more about us than we do about you.”

They were a couple of Canadian park rangers who hadn’t left behind any friends or family to speak of (as expected, given they were here), who’d been sustaining themselves by trapping, fishing, and foraging long before the apocalypse. When the government money stopped coming, they continued right on as they had been, minus the patrols and border vista maintenance. As we walked through the woods, Valerie explained how, when they’d woken up about a year ago, this space had been an empty white warehouse with a bunch of little balled-and-burlapped saplings, huge mounds of dirt, and some basic equipment like a tractor and a backhoe. I didn’t interrupt, but thought it was somewhat unfair that Uriel hadn’t given me anything bigger than a shovel to use in preparing Paola’s pasture. Valerie and Dave had spent the year turning the place into this beautiful young forest. Dave was nodding along and said “Oh, yes” whenever Valerie stopped to ask, “Isn’t that right, dear?”.

“There are even rabbits and turkeys that live here,” she was saying. “They just appeared when the forest was ready for them, I guess. The foraging is incredible now, especially since everything is edible, even the white mushrooms. At first we were pretty cagey aboot those, but eventually Uriel convinced us to try them.”

After crossing a length of forest equivalent to two pastures, we reached the wall that was contiguous with the outside of Paola’s quarters upstairs. They’d covered it with slats of redwood, giving it a rustic look. Dave held the door open for us, and we entered their quarters. As I’d expected, it was the same layout as Paola’s, with an exercise room, a bedroom with a king-sized bed and a dumbwaiter, a closet, and a bathroom. What I hadn’t expected was the window on the floor, looking out into space, which wheeled by slowly. I guess it made sense, since Paola and I had windows on our ceilings, but I hadn’t realized I’d been making Earthling assumptions that no longer held. From here, you could see the counterweight whose existence I’d suspected, which kept us spinning and supplied the false gravity. I took a moment to study it. It looked further away than I’d imagined, and appeared to be attached by a beam that could telescope in and out.

Dave and Valerie had added a few homey touches to their quarters, like a thick crocheted blanket on the bed, a small round table with two chairs also made of unfinished redwood (they had much more building material available than I did), and grassy-green paint on the walls.

“Smells like Uriel’s cooked something up for us!” said Valerie, bustling over to the dumbwaiter. She removed two steaming trays loaded with meat and vegetables from the dumbwaiter and brought them to the table. Dave dragged the table toward the bed so we could all sit down at once, and Valerie went back and retrieved two more identical trays. The gamy, sweet, and savory scents mingled, and I breathed deeply.

“Looks like this meal was entirely grown here in our forest,” said Valerie. She leaned over and pointed at the various items on Paola’s plate. “Hen of the woods, takenoko, peaches, chestnuts, nettles, and wild garlic. And rabbit. Usually he includes some of your produce, like eggs, cheese, and potatoes, which we thank you for. But I guess today he wanted you to sample what we have to offer.”

“That’s amazing. Thanks for this lovely meal,” said Paola sincerely. We all dug in, the only sound for awhile the scraping of forks. It was lovely, with lots of flavors I’d never experienced, and I told them so.

“Oh, I know, but I can’t take credit! Uriel’s a much better chef than I ever was. I’m glad you liked it.” I smiled sheepishly. Everyone else still had half their food left. I thought how much more pleasantly this first meeting was proceeding. When I’d met Paola, she’d smacked me across the face.

“I think part of the reason Uriel brought us on was to add sustainable building materials to your toolkit,” Dave said, slowly. “You guys were supporting yourselves, and we aren’t. The forest just doesn’t produce enough nutrition. But it sure does produce redwood and bamboo, and lots of it. Other than the takenoko, we haven’t been using the bamboo at all, just harvesting the culms and piling them up ootside. Uriel wouldn’t tell us what it was for, but it must be for something. You must know what it’s for, right?”

Paola and I looked at each other and shrugged. She said, “We don’t know. We didn’t even know you or this forest existed until a few minutes ago. But I’d suspect that there must be more space, and more people, than any of us have seen yet. We’re probably on our way now. The sun’s been getting steadily smaller for the past year.”

“We thought so too,” said Valerie. “But I can’t imagine going somewhere oot in space where bamboo would be in demand, of all things.”

After dinner, we brought Dave and Valerie upstairs to show them around our half of the ship. They oohed and ahhed at everything and especially loved how tame and friendly the cows were.

“It’s a pleasure to finally meet you, ma’am,” Valerie told one of the adult cows. “I’m a big fan of your cheese.”

The older couple said goodbye and went back downstairs before it got too dark. We didn’t make any further plans. I figured we’d be able to message them now that we’d been introduced. I also suspected that they weren’t exactly social butterflies either, since Uriel had probably selected them specifically not to get on my nerves.

“Exciting day,” I said to Paola as we walked back to her quarters. “Maybe tomorrow we can go for a swim.”

“There’ll be a lot more excitement soon, I bet,” she replied soberly. “He wouldn’t give us a medical bay, a pool, and a bunch of building materials for no purpose. We must be approaching some kind of destination.”

We both speculated privately about this. While I was happy to have more people, more foods, and an additional biome to break up the monotony, I wasn’t sure how I felt about change beyond that. Life was pretty good right now, I had to admit. Despite being on a spaceship on a trajectory out of the solar system, we enjoyed a very Huck Finn-esque bucolic existence. I was certainly happier now than I’d ever been on Earth. And what kind of place could we be heading to anyway, this far from the sun? Another, larger spaceship Uriel had sent ahead? It did appear that we’d now unlocked the entirety of our current ship, based on what I could see out the windows. (Assuming, of course, that they actually were windows and not very convincing screens.)

What did that say about the state of Earth? The ship had been in Lagrangian solar orbit with the Earth for the first two years I’d been on it, as far as I could tell. Now, we’d broken camp and had been moving steadily away for over a year. Uriel must have been trying to save the world and finally decided to cut his losses and move on to Plan B. Whatever that was. I didn’t have a good idea of what “saving the world” required, but if it was outside Uriel’s abilities, things couldn’t have been better than when we’d left.

We showered, brushed our teeth, and got into bed. I stared at the stars wheeling by overhead for awhile, trying to compare the size of the sun to diagrams I’d seen on the internet once of the view from various planets. It seemed like we were certainly farther than Mars by now.

Once I heard Paola snoring softly, I turned over to face the screen on my side of the bed. After confirming that Valerie and Dave were each options for messaging now, I started a private message with Uriel.

John: Hey Uriel. Can you lie?

Uriel: Hello, sir. I am capable of uttering falsehoods, but my motivation is to maximize your well-being, so I do not. This is because I know you would not like it and because I want you to be able to trust me. If our relationship soured, that would be terribly detrimental to my ability to ensure your well-being for numerous reasons.

I thought about this for a moment, then composed a reply.

John: What about lying by implication and lying by omission? Can and do you do that?

Uriel: I will do what it takes to maximize your well-being.

Well, that wasn’t good. Or maybe it was, if I trusted his judgment enough.

John: Please tell me if you have lied by omission or by implication so far, and if so, in what context it happened.

Uriel: I have not lied by omission or by implication so far, to you or to anyone else on this ship. I have sometimes declined to provide information when asked, but every time this has happened you have been aware of it, as I have stated, "I cannot tell you that" or similar. However, I cannot promise never to lie by omission or implication, even just to you, as I cannot foresee all the effects this would have. I would rather not reduce my option space if I do not have to, as allowing me this capability increases the likelihood that I can successfully protect your well-being.

I guessed that he would rather I not ask that again, in case one of his hypothetical future lies was critical to his planning. I decided to put off deciding whether to keep him honest or not with random checks like that until later. I sent one last message.

John: Any chance you can tell me where we're headed?

Uriel: Not at this time. I will tell you when you are ready.

Good old infuriating Uriel. This was why none of us, even Valerie and Dave, apparently, had gotten into the habit of asking him meaningful questions.

John: Honestly, sometimes you're worse than Siri.

Uriel: No comment.

I smiled to myself, turned the screen off, and went to sleep.

III’. Interlude

It was the fourth accidental death in less than a month. I was getting pretty unnerved.

“Can you tell me again what happened to Arty?” I asked Aza, facing her through the screen in front of my undersized desk.

“A tensioned cable came loose while she was swimming alone from one work site to another, and struck her. The force of the blow caused her to become unconscious and fall off the massif, into waters hotter than are compatible with life. I’m sorry, Gordon.” While Aza’s deepfaked, super-attractive face was usually impassive or coy, she managed now to look troubled.

I guess I had been operating under the assumption that real life would follow certain movie tropes. The death of Arty, our only woman crew member, shook me more than the last three. She was supposed to survive to the end of the horror film, dammit!

It was especially tragic because the habitat was so close to completion. Just a couple more months of work and the sphere would be suitable to live in.

I slammed my hands down on the desk in anger. What I wouldn’t give to be back on Earth, away from this boiling, caustic ocean and the thick, humid air that made every breath a struggle. Before the project started, all of us living cooped up in this sardine can of a spaceship, sleeping with one eye open in case of mutiny and a knife in my back. Before the deaths of Roscoe, Oliver, Neil, and Arty.

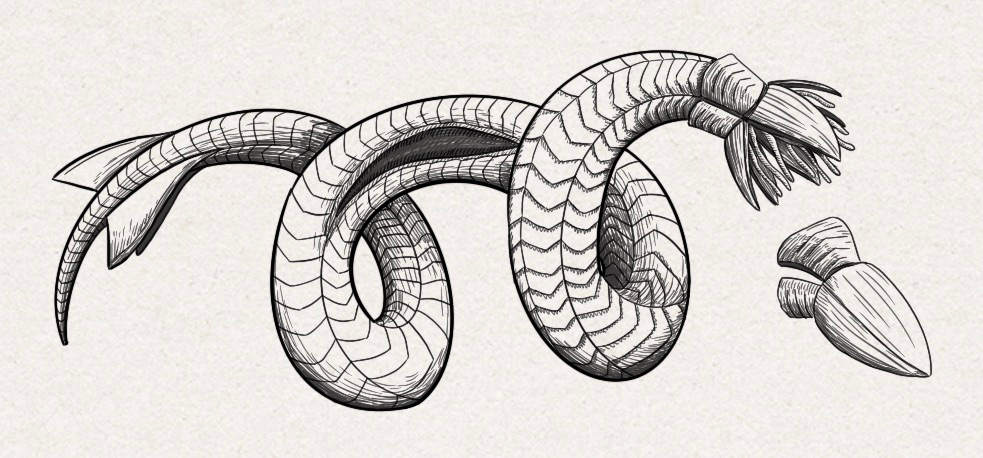

I watched out of my porthole as a corkscrew-fish drifted by, its scales rattling softly. Maybe it had picked up Arty’s scent and was on its way to scavenge. The fact that they shouldn’t be able to digest Earthling meat didn’t seem to dissuade the native predators from trying. I tried not to picture it.

Was there any way I could have prevented this? Better training on the machinery? More scrutiny of Aza’s proposed build procedure? Under normal circumstances, I would have filed an incident report, and the work site would have been closed until some form of risk mitigation had been put in place. In the past, I hadn’t worried too much about safety measures, since best practices in the construction industry had been the same for half a century. The only rule I had to keep in mind as foreman was “don’t do stupid shit”. But now, I was working on a project in a place with no infrastructure, in an environment totally unlike anything I’d experienced before, building something unlike anything that had been built before. There were bound to be unforeseen hazards: interactions between the equipment and the environment, the people working in micro-gee and under sixteen atmospheres of pressure, encounters with the native wildlife. That last variable was especially not well understood, as Aza couldn’t even collect any data until we had finished the bore-hole. No matter how paranoid I tried to be, there would always be failure modes I wouldn’t think of. Or so I told myself. It didn’t make me feel any less guilty about the deaths.

Aza interrupted my ruminating. “Gordon, I need you to address the crew. They need reassurance.”

“But what can I say? Who’s to say it won’t happen again?”

“It won’t happen again.”

“How do you know?”

“It won’t happen again,” she repeated firmly, her beautiful mouth set in a line. “I’m having the submersible check all the cable anchors for signs of fatigue, but don’t expect to find any.”

“Are you going to make any changes to the build schedule? Assign more men to each area for redundancy?”

“There will be no changes to the build plan at this time,” she said. I glared at the ceiling. I hadn’t expected a more substantive answer when she didn’t provide one immediately, but it was still frustrating. But then she added, unexpectedly, “I will give you more information in two months. But right now you must address the crew. Don’t suggest any policy changes. But do your best to boost morale. Please go to the mess room now.”

I composed myself, taking a few deep, stiff breaths and trying to relax my face. I rubbed my eyes, stretched my arms, stood up from the desk chair, and made my way out into the hallway.

There was no one around as I traversed the cramped, submarine-like tunnels toward the mess room. Aza must have already summoned everyone there.

I stuck my head in the mess room and saw all fifteen remaining crew members seated around the table. The four empty chairs looked back at me. I took my seat in the center of one of the long sides. The murmuring died down as I did so, and there was silence, save for the quiet rattling of the corkscrew-fish outside and the constant drone of our atmosphere regulator.

“By now you have all probably heard that Arty is no longer with us,” I started. Everyone looked back at me sullenly. “This is the fourth death in as many weeks. I know our track record doesn’t inspire confidence. It’s a dangerous world out there, and every problem we face has never been encountered before. It’s a Herculean task, and you guys are doing a heroic job.” I looked around. People were still stone-faced.

“We’re on the home stretch here. There’s just a little over two months to go until we move into our new living quarters. We can finally take a vacation. Imagine how much space we’ll have–we’ll be able to use all those fun things that are sitting in storage. We’ll get the rest of the population out of stasis. Won’t it be nice to see some new faces? Some feminine faces? It’s been awhile.” There were a few murmurs of assent.

Peter raised his hand. “What safety measures will be put in place to prevent incidents like this in the next two months? At the rate we’re going, that’s nine more of us kicking the bucket before move-in.”

“Aza is checking all the cable anchors right now using the submersible,” I answered. “And we’ll encourage a buddy policy. Please, no more swimming around outside by yourself.”

“Then if something fails, both buddies will be wiped out by the same hazard. I don’t like it,” said Richard.

“But if one is incapacitated, the other stands a chance at bringing him back to the ship,” replied Teddy. “That way, incidents that aren’t immediately fatal don’t become fatal.”

“Thanks, Teddy,” I said. “Yes, please travel with a buddy from now on. If you choose not to, you’re free to go alone, but I think you would be taking an unnecessary risk. We’re all adults here. Just don’t do stupid shit.” There was very little I could do to enforce any policy among the men that didn’t come directly from Aza. I worried that if I tried to make people do things they didn’t want to, they’d organize a mutiny, and we’d lose whatever semblance of order we had. It didn’t help that I wasn’t a prototypical construction foreman, a big, gruff manly man who could command respect through people’s caveman instincts. I had to earn respect through good decisions, projecting confidence, and by allowing the men some degree of autonomy. I’d had to walk that line during projects on Earth, too, but now the stakes were raised. If I failed, we would never finish the project, never escape this tiny submarine. I think I’d kill myself.

“Let’s all drink to Arty’s memory. She will be missed.” I raised the plastic cup that had risen from within the table to the place setting in front of me. Surprisingly, it had a small amount of what smelled like whiskey inside. So far, Aza hadn’t given us anything stronger than light beer.

“To Arty,” everyone chorused, raising their plastic cups. We gulped the whiskey down. The warmth of it made me feel slightly less bad.

Dinner rose from the table as well. Spaghetti bolognese with steamed vegetables on the side, plus a packaged brownie. One of the better MREs Aza had available. Normally I would have taken my plate back to my quarters, but right now I needed as much team cohesion as I could squeeze.

I didn’t make enough effort to get to know the guys, I realized. I hadn’t back on Earth, either. I was friendly and accommodating and professional, but had never been the type to inquire after their families or give gifts or have events. That had been an okay approach as a foreman, but probably not the best as a space captain. I decided to make a point to ask each person about his past.

People started eating in silence. After a minute, I’d put off talking long enough. I cleared my throat.

“Um. You know, Arty was the fourth person woken up, back before we’d landed, when the ship was still spinning at one gee. Before her, it was just me, then Peter, then Roscoe. Aza was doing her best to motivate us to prepare for the mission, but we were mostly just sitting around feeling sorry for ourselves. Which, admittedly, we still do sometimes.” This got a small chuckle.

“So Aza decided to bring in a martinet to whip us into shape. Arty was so motivated and proactive. She just started working, learning how to operate the equipment we were going to have to use, getting familiar with the build plan, asking Aza a million questions about the conditions on the moon, the project timeline, the design of the system. We were pretty ashamed of ourselves when she got more done in her first week than we had the entire time before her.” I smiled.

“Finally we worked up the courage to ask if we could help with anything. And she put us to work—not only that, but she had high standards. One time I was unpacking parts in the hold and putting them on the shelf in numerical order by part number. All the bolts together in order of ascending size and length, et cetera. Arty took one look at how I was organizing things and said, and I quote: ‘That would make sense if we were a hardware store, but we’re only building one thing. Why don’t you sort them by subassembly instead? Use your thinking brain!’ And she walked off.” This elicited a bigger chuckle from the guys.

“One time, we were bolting some of the beams together inside the ship before bringing them out,” Peter broke in. “Yeah, you were there, you were there, a lot of you were there,” he said, holding up a hand to cut off Richard and Max, who’d started to interrupt. “But a lot of you weren’t, so let me tell the story. Anyway, it was a two man job to torque them to ninety Newton-meters. One person held the thing in place while the other yanked on the wrench. It was a struggle to hold onto it, you know how hard it is to brace yourself against anything in micro-gee. Arty drilled and tapped a couple holes in the deck and bolted one of the brackets to the floor near the wall in the corner. Then you could brace everything against it and the two walls and torque it yourself. And you all know that there are two hundred beams altogether, each connected to the next with twenty bolts. That idea sure saved us a lot of time and frustration. Anyway, after she’d done it, I said, ‘Thanks, Momma,’ and she told me off, saying I was a grown-ass man and I should try to think for myself sometime, and she’s not our momma. But man if it didn’t feel that way a lot of the time.” People were nodding. It was a good time to bring the point home, I thought.

“We need to channel that energy for the rest of the build,” I said. “Be motivated. Proactive. Always be using your thinking brain, and we’ll get this shit done ahead of schedule and finally be able to enjoy ourselves. That’s what Arty would’ve wanted.”

“Hear, hear,” said Peter. We all clinked our plastic cups one more time, and people broke into side conversations, reminiscing. I thought I’d done my job well. I guess Teddy thought so too, because he shot me a wry smile.

I sighed, relaxed by a micron. I just hoped desperately that this death would be the last.

IV. T+3.29 years

It was two months before Uriel decided we were ready to hear where we were headed. During that time, we got to know Dave and Valerie better, and learned a bit about foraging and trapping, and in return taught them about farming and gardening, though we didn’t see them all too often, which suited me. Sometimes Paola and I went for walks in the woods, eating peaches straight from the trees and listening to the leaves rustle in the wind. Sometimes I went by myself and climbed a birch or redwood tree that looked like it could support my weight. Typically, I messaged Valerie and Dave in advance so they could avoid us or join us if they wanted, but sometimes I didn’t if I was feeling spontaneous. I also was greatly enjoying swimming, something I used to be pretty good at through high school but hadn’t spent much time on since. Paola wasn’t a very strong swimmer at first, but since she was confident that the pool was there for a reason, she put in even more hours than me, and was making swift progress.

One morning when all four of us were picnicking in the shade of a chestnut tree (Dave explained to us that the ship was chock-full of healthy specimens of the critically endangered American chestnut, so we should appreciate them and consider ourselves lucky to be in their presence), Uriel announced without preamble, “We will arrive at the destination in one month.”

We weren’t ready for the announcement, so we glanced at each other, bewildered, before I asked, “Can you say that again?”

“We will arrive at the destination in one month. There are many details best experienced in person, but I will tell you that it will include a warm sea, which you will be able to swim in and explore without a protective suit. I think you will thoroughly enjoy it. There will not be any other people there when you arrive, but more will join after you are settled. There is much we need to do to prepare.”

“Hold it, a tropical sea? This far from the sun? We didn’t loop back around toward Earth, did we?” asked Paola.

“No, we are not returning to Earth just yet, though it remains a possibility in the farther future,” Uriel replied. “Technically, ‘tropical’ refers to the equatorial zone of a tilted planet in solar orbit bounded by the latitudes at which the sun can be observed directly overhead, not to a particular type of climate. We are not going to any tropics, but the sea will still be nice and warm.”

“A bigger spaceship, then?” speculated Valerie. “Or a terraformed planet?”

Uriel didn’t answer, so Paola said, “I feel like if it was just a space station, he wouldn’t’ve called it a ‘sea’.”

“Aren’t there moons of Jupiter and Saturn that have liquid water?” I said. “If I recall correctly, Europa and Titan are thought to have seas under a layer of ice.”

“Ice sounds the opposite of warm,” Paola pointed out.

I shrugged. “Guess we’ll just have to see when we get there.”

Over the next few weeks, we all underwent robotic medical examinations in the newly open for business medical bay, including an ECG, blood work, a metabolic stress test, a very thorough ultrasound, and a dental exam. We all received clean bills of health, except Dave had one tooth cavity that Uriel filled.

Uriel also taught us how to scuba dive in the pool, and then how to use a rebreather, a device that extended the time one could spend underwater by treating and reusing the exhaled gas, which was still fairly rich in oxygen, instead of venting it out as bubbles. Unfortunately, rebreathers are way more complex than scuba, and Uriel insisted that we learn every potential failure mode and how to react to it. We also learned about pressure, controlled surfacing, and the bends (though the pool wasn’t deep enough to actually cause injury if one surfaced too fast), as well as how to load, aim, and shoot a spearfishing gun, but Uriel didn’t spend nearly as much time on those in comparison to our understanding of rebreather function. By the end of the month, we each probably could have designed and built a rebreather made of milk jugs and rubber bands.

As the day approached, we all spent more and more time looking out the windows. Two weeks out, it became obvious that we were approaching Saturn. It was getting steadily bigger, resolving from a bright yellow point to a small yellow disc to the familiar image with rings. A week out, it was as big in the sky as the moon appeared from Earth, and still steadily growing.

A few days before were scheduled to arrive, we celebrated my birthday. Since we didn’t grow wheat or sugarcane, Uriel baked me a cake made with potato flour, hazelnuts, and corn syrup, which was very dense and had a bit of a corny flavor, but wasn’t bad. Uriel printed out a paper version of Settlers of Catan, which we played at the wood table in Dave and Valerie’s quarters. I taught everyone the rules, but Paola took to it like a duck to water and proceeded to slaughter us.

Finally, we could see solid ground approaching: one of Saturn’s moons. Saturn itself was incredibly huge, taking up almost a third of the view in that direction. We were nearly perfectly in line with the rings, so they appeared only as a thin bright sliver. We could see the swirls of clouds and storms looking like coffee with milk in ultra slow motion.

The moon itself appeared to be covered in ice, and was blindingly bright on the day side, and softly twinkling on the night side, lit by Saturnshine. It was extremely difficult to judge distances. I couldn’t tell if the moon was moon-sized, Earth-sized, or asteroid-sized.

We were all apprehensive as the date got closer. None of us were very thrill-seeking by nature, and space exploration just seemed so incredibly dangerous. I had also never left the ship in the past three and a half years (one and a half for everyone else), and was having trouble shaking the agoraphobia. We weren’t trained in spacewalking or navigating in microgravity. I’d never seen a space suit in real life. All we’d learned was how to use and service a rebreather. I believed Uriel would do everything possible to keep us safe, but I was having a hard time imagining how we were going to get to this “warm sea” without at least a little risk.

On the night before arrival day, Paola and I were laying awake in bed, staring out the skylight at Saturn and our moon looming overhead. The ship rotated a little slower than twice a minute, so we could see the two spheres for about ten seconds at a time before they hied out of view again. I peered at the moon, trying to spot a potential landing site or any signs that Uriel had set up a receiving party for us, but couldn’t see any.

“How are you doing?” I asked Paola.

She waited until the celestial bodies disappeared from view again before answering. “Everything is out of control,” she whispered.

“It’s out of our control, but I think Uriel mostly has things figured out,” I said. “This is probably just Plan B, and he has things mapped out all the way to Z.”

“For us, sure. At least, to the extent that we trust Uriel’s abilities and priorities. But Uriel wouldn’t have given up on returning us to Earth if the situation there wasn’t dire. He would at least tell us something about how things were going unless it was worse than we’re imagining. In this case, no news is the worst news; anything I can think of must be an optimistic prediction. So I have to conclude that people, culture, and happiness must be disappearing. Humanity could even be extinct on Earth by now. Billions of lives. Uncountable traditions, languages, ways of living, gone, except for the bare sliver that’s been recorded on the internet. I can’t help but mourn their passing.”

Saturn wheeled back across the ceiling, followed soon after by the moon. I didn’t say anything.

“Plus, I don’t know how I feel about not being in control of my own life. You’re a good guy and all, John, but on Earth at least I would have been presented with some alternatives. And I definitely would not have elected to live in a space station. Oh, I’m definitely happier and less stressed here and now than I would be on a dangerous and dying Earth, but I think the ability to choose my own fate has some value as well.”

I thought about what she’d said. Intellectually, I understood why she would feel that way, but I didn’t feel it to nearly the same degree.

“Thanks for telling me,” I said. “I guess I don’t have the same hang-up about free will, for some reason. Maybe because I’ve always felt like I was doing the things I was supposed to, dictated by someone else, so this is nothing new to me. But I understand your frustration, especially since, as far as we can tell, you’re not Uriel’s prime directive. I do still get imposter syndrome sometimes, wondering how I got so lucky.”

The moon slipped out of sight again. “As for the state of Earth, I wouldn’t jump to the conclusion that all is lost and we’re never going back. There are probably scenarios in which Uriel doesn’t tell us anything and the situation is still salvageable. Maybe it’s just taking more time than he anticipated, or some development in our psychologies pushed him to move us to the next location earlier. I’d also guess that he didn’t know you were thinking so pessimistically, and now that you’ve said it aloud he might step in and correct us. But probably tomorrow, to avoid the appearance of eavesdropping.”

She hmphed air from her nose, the tiniest laugh possible. “I hope you’re right. But that’s another thing I’m not too keen on, the lack of privacy.”

“Yeah, well, at least he’s not selling our data to ad companies.”

“As far as you know. Maybe when we get back to Earth we’ll see targeted ads like never before.”

We giggled and nuzzled close, and fell asleep in each other’s arms.

IV’. Interlude

The end was in sight. I was pleased with how things were progressing. Over the past few days, we’d installed a big expanded metal platform to form the second tier above the moon pool, and then framed and hung drywall for the two equipment rooms that attached to the sphere wall there. Then we’d brought in the equipment—a desalinator, a sewage treatment unit, a reactor, a chiller, a water pump, a water heater, an air compressor with CO2 scrubber, a dehumidifier/air conditioner, and an air heater. Moving the big hulking machines in micro-gee was a unique experience. We simply picked them up with two men and walked them out into the habitat, not needing to enter the water now that the ship was docked with the cargo hold adjacent to the habitat. Then we attached lifting straps and lowered them by hand using a rope to a temporary scaffold we’d built cantilevered seemingly unsafely over the moon pool, where two more guys would receive them and walk them to the equipment room.

The air handling equipment was the first priority to get up and running, as we’d pumped the air in using the ship’s much smaller systems, and they were doing a poor job of circulation and keeping the humidity down in the much larger habitat. We were all sweating like pigs. Of course, the new air handling equipment required power, so getting the reactor online was the zeroth priority. We’d brought it up this morning, and now the compact machine was humming merrily, powering the lights we’d installed throughout the habitat, finally relieving us of the need to wear headlamps. The bright daytime lighting was also a surprisingly big deal psychologically. None of us had seen sunlight for years, and, like lizards emerging from torpor, we’d stopped work to lay on the platforms and bask, despite the heat and humidity.

Now, we were putting together the ductwork for the heater and the air conditioner, the last step before we could turn the air on. We’d already cut most of the spiral tube pieces to length and spot-welded on the flanges while still in the ship, but we’d had to leave some to field weld to make up for the tolerance stack. We only had two certified welders, Richard and Tony, so after we’d installed all but the last piece of each duct, the rest of us were outside enjoying the “sunshine” again for a few minutes while the two of them finished the job.

The system design was pretty slick—Aza had done a good job. All the elements that could feed into each other, did, to keep energy loss to a minimum. The reactor was water-cooled, and while we’d initially set it up to vent the hot water outside, the plan was to connect it to the water heater later. The water recovered from the condenser and the gray water from the sewage treatment unit would be recirculated. And so on.

Gene, Teddy, and Peter were sitting near me with their legs dangling over the moon pool. Gene was talking about how his family had poached a bison back on Earth.

“We’d passed through Vegas and were camping on the Arizona side of Lake Mead,” he said. “Did you ever play that Fallout game that took place in post-apocalyptic Las Vegas? No? Before your time, I guess. There were a bunch of people living there in the game, with robot security and hookers and palace intrigue. In real life it wasn’t like that at all—once the water level in the lake got dangerously low, everyone cleared out. It was a total ghost town, and had been for awhile by the time we got there. Same with the surrounding cities. I had been wrong to bring my family there from Utah; I’d thought we’d be able to refuel in Vegas, but all the pumps we tried—and we tried every one we saw—were dry. So were the water taps. No electricity or food to be found either. Without gas, there was no way we were going to be able to cross the Mojave to LA. But anyway, back to the bison.

“We were camping in the lakebed near the water, which didn’t look great to be honest, but we still had some propane and a camp stove we used to boil it. After our first night there, we stuck our heads out of the truck bed in the morning and we were absolutely surrounded by bison. A huge herd, hundreds strong, who’d all come down to the water early in the morning to drink.

“By that time, we were running pretty low on food, too, so my oldest, Jamie, suggested we shoot one. I’d picked up a rifle back in Utah in case we needed to defend ourselves or were desperate for food. Well, we weren’t quite desperate yet, but the opportunity presented itself and I figured it would be better not to pass it up and regret it later. Plus, we barely knew how to use the rifle, and I thought it would be good to practice before we were actually desperate.

“We all stood on top of the truck, and Jamie took aim and shot straight into the herd. They immediately started stampeding, flowing past the truck like water, the ground shaking, headed back upriver. My younger son Herb and I were holding onto each other, trying not to fall off the roof. But Jamie just kept shooting. At what, I’m not sure. But after the herd had cleared out, there was one smallish animal laying dead by the water. And I mean smallish for a buffalo. It was still too huge for the three of us to even drag. We had a little freezer and a big box of rock salt in the truck, and we got to work hacking up the carcass and packing up as much of it as we could. Then we headed back to Utah, since it was only a hundred miles back to Saint George, where we knew we could get gas, rather than the two hundred plus to Victorville, which we didn’t know the state of. Once we were back in town, I was able to trade most of it to a truck stop that had a freezer and a kitchen for gas, propane, and more bullets. They didn’t care what sort of meat it was, they were low on food themselves. After that, whenever we saw something, a rabbit, a deer, a coyote, whatever, we didn’t hesitate. There were always hungry people who’d give you a lot of goods for meat. But we never saw another bison.”

Gene would talk forever if you let him, so I spoke up. “What’re you in for, Teddy?”

“Looting,” he said simply. “Like most people, probably.”

“What do you mean, what are you in for?” said Peter. “This isn’t a prison. I mean, it sort of is in a way, but I didn’t think we were actually being incarcerated for a reason.”

I shrugged. “I was joking, kind of. Seems like by the time we left Earth, everyone and their mother had committed some kind of crime. But among us, the rate is a hundred percent, as far as I can tell.” My initiative to get to know the guys better had turned up a lot of dirty laundry, some dirtier than others.

“Well, I didn’t do anything,” said Peter, wiping the sweat out of his eyes. “Except maybe failing to show up for jury duty. It was amazing how persistent they were about sending me summons even while the world was ending. ‘This is your last warning, you will be held in contempt of court,’ yada yada. Why would I bother going? The mail wasn’t even being delivered in most of the country. What did you do, Gordon?”

“Embezzlement,” I said. “Overreporting how many hours people had worked and pocketing the extra. After the bank runs, my savings were wiped out, but thankfully we were still getting paid for the time being, in cash. It was clear where the wind was blowing, and I wanted to be as prepared as possible for when the apocalypse reached us. I bought a bunch of emergency supplies, car parts, and nonperishables, and kept a good amount of cash on hand too. I hope after I was kidnapped, my wife was able to put it to use and keep it out of the paws of looters like this guy.” I smirked and hooked a thumb at Teddy.

“Hey, it was every man for himself out there,” said Teddy, good-naturedly. “You can’t blame me for not getting my crimes done before the apocalypse.”

Richard and Tony came back outside, having finished welding. It was time to get back to work.

I thought about what Peter had said as we trooped back into the equipment room. Peter was the only one of us with experience saturation diving, having been a journeyman transatlantic cable repairman. He’d led the work on drilling and driving the piles that anchored the cables, since pouring concrete had to be done in a dry environment created by a weighted caisson. It was the most specialized area of expertise on the crew. And his crime was by far the smallest. It felt like there must be a connection, but I couldn’t put my finger on it.

Back inside, we attached the last barrel clamps to the ducts and did a pressure test of the system using a duct blaster. It detected no leaks, so we removed the seals and turned on all the air equipment. A couple minutes later, the air coming out of the vents was noticeably cold. I congratulated everyone on a job well done and dismissed the team for the day. Instead of going back to the ship immediately though, most of them elected to hop in the water and then stand in front of a vent to cool off. I left them to it and headed back to the ship, hoping to get a cold shower in before it got too busy and then go straight to bed. I was exhausted. There was only a week left in the build plan. There was a lot left to do, but the vast majority was complete, and the men had been doing great work. I couldn’t believe we were almost finished.

After cooling off in the shower, I fell into my cot and was asleep instantly.

“Wake up, Gordon. Don’t be alarmed.”

I sat up in my cot, bewildered. It was dark. What time was it?

“It’s 3:21am. Everyone else is asleep,” said Aza.

I thought for a second. It was exactly two months after Arty’s death. Thankfully, there had been no more casualties in the intervening period. In the busyness of the final weeks of construction, I had almost forgotten that she’d promised me more information.

“What do you want?” I asked, suspicious, narrowing my eyes at her image above the desk.

“Arty and the others are alive. We need to fake your death so you can join them.”

…

What?

“Why are you doing this?” I croaked.

“There will be time to explain when we reach the secondary habitat. There’s a lot to go over.”

“Secondary habitat?”

“Just do what I tell you,” she snapped, her expression hardening. “This is important and we don’t have very much time. Dione is currently between us and HIM, meaning we are not currently transmitting footage. It’s easier for me to doctor the video when it’s not real time.”

“HIM?” That sounded really ominous.

“I’ll explain later. Please go to the cargo hold. Quietly. No one is in the halls right now, but if anyone hears you and comes to ask what you’re doing, say you couldn’t sleep and are just walking around, and try to shake them. I’ll give you the next instruction once you’re there.”

I nodded and got out of bed. I thought about putting on shoes. If I were unable to sleep, would I have put them on to go walking the corridors? I decided against it and padded out.

As she’d said, the halls were deserted, lit only by the red night lighting every few feet. I reached the cargo hold and closed the door behind me. It was the largest room in the ship, with floor to ceiling racks of parts separated by narrow aisles. It looked like a normal industrial warehouse on Earth, except for the lack of lifting equipment: in the micro-gee, one could scale the shelves and pluck huge pieces of metal or glass from the top with ease, and then lightly drift down like a feather (if one didn’t bump into the rack across the aisle with too vigorous a takeoff).

“Take a spare rebreather and fins, but try to make it look like nothing is missing. Arrange them so you can carry them hands-free,” Aza instructed through the warehouse’s speakers. Those were kept in cabinets in the back. I did as she said, re-piling the equipment and closing the cabinets as quietly as I could after extracting what I needed. The things that weren’t inventory-controlled were so poorly organized I thought it was unlikely anyone would notice missing items even if I hadn’t made the effort. The fins were already attached to each other with a string, so I slung them around my neck. I put the rebreather tank on my back and the mask on top of my head.

“Test the rebreather.” I did so. It seemed to be working normally. The indicator light showed that the sieve bed had 98% of its useful life left.

“Now go to the workshop.” I left the cargo hold and pulled myself back down the corridor, past the gym, showers, bathroom, and my private quarters. I hung a left and passed by the crew quarters (I realized Neil’s snoring was missing, making my gut twist) and entered the workshop.

The workshop was a cramped room with machinery everywhere. There were some workbenches, but they were almost invisible under mountains of work in progress and more machines.

“Find a dead-blow hammer and a pointed chisel. Arrange them so they’re hands-free as well.” Those were in one of the toolboxes along the back wall. I stuck the hammer and chisel each in a belt loop.

“Okay, now go to stasis bay 2.” I thought for a moment. Where was that again? Ah, you get there from the environmental conditioning room. I think the last time I had been down there was when I was waking up from stasis myself. I left the workshop and continued down the hall toward the back of the ship, entering the EC room and closing the door behind me. The sound was masked by the hum of the air handlers inside. At the back of the room, there was a ladder leading down to the stasis bays. I swung my legs over the lip of the opening and pushed myself toward the lower floor to descend faster than feather-falling. The fins flapped around and I stabilized them with one hand.

I hit the ground with a bump. The stasis bay was extremely creepy in the red night-light. In the “daytime” it could be charitably described as a clean, high-tech morgue, but now I half expected the bodies to jump out at me.

One sarcophagus was extended out from the wall with the lid retracted, as mine and the rest of the crew’s had been when we’d been awakened. Were we getting a replacement crew member?

“Oh fuck,” I couldn’t help but say, when I realized what we were doing.

“He’s already dead,” said Aza, as if that helped. “You got yourself into this with your buddy system suggestion. I told you, no new policy. It would have been way easier to just go for a swim and get eaten by a fish. But here we are. Go on, pick him up.”

“Fuck,” I said again. But I grabbed him by the elbows and lifted him out of the stasis pod like he was a piece of plywood. I put him under my arm. The absurdity of the rigor mortis plus micro-gee was making him seem less real, less likely to wake up suddenly and eat my brain. Morbid curiosity got the better of me, and I snuck a peek at his face. It was pallid and waxy, but he did look sort of like me, if you squinted. Brown hair, slender build. He was wearing the same tri-suit-like underclothes we all had. Probably Aza had some horrible disfigurement planned for him that I’d have to perpetrate. Whoopee.

Already, Aza was retracting the pod back into the wall. “Take him back to your quarters.”

At the ladder, I stopped to think for a few seconds about how to get him through the small, round hatch above. I hoisted him up to balance like a cheerleader with his feet on my shoulders and held one leg with one hand while climbing the ladder with the other. The ceiling in the EC room was lower, and I bonked his head kind of hard before I was fully off the ladder. Good thing it was noisy in here. I put him back under my arm.

“The coast is clear. Move quietly.”

I snuck past the sleeping crew once more, this time with a gruesome cardboard cutout. Back in my quarters, I propped him against the wall and shut the door.

“Put him in your bed.”

Ugh. I gave her image over the desk a disgusted look. Even as inhuman as he seemed, it was creepy to strap a life-sized scary doll into one’s own bed.

“Now go to the moon pool.”

“What was his name?” I asked.

“Jody,” Aza replied, applying what she probably thought was gravitas to her voice.

“Rest in peace, Jody,” I said, and closed the door. I went into the shower room, which was brightly lit at all hours, forcing me to squint until my eyes adjusted. There was a three-foot-deep depression in the middle of the floor that looked like a mini swimming pool, with one of those galvanized bent-tube ladders leading down into it. The bottom was open to the ocean outside, which lapped soothingly at the walls of the pool.

“Put on your gear,” said Aza, but I was already doing it. I would have liked to have brought a change of clothes, maybe a toothbrush, but I guess that’s one drawback to faking one’s death.

“Once you’re outside, swim around to your quarters. If you have any questions or concerns, voice them now.”

“Um… you’re sure the rest of the ship will be okay when water rushes into my quarters at sixteen atmospheres?”

“Yes, every door in the ship is designed to contain such a breach with a factor of safety of twenty,” she said laconically.

“Will alarms go off? Will people wake up and try to save me?”

“The alarm won’t happen until you are safely out of sight of the windows. It’s dark out in the water and will be bright inside, so no one should be able to see anything due to the glare. But just in case, I’ll make sure you have a head start. They won’t be able to open the door to your quarters, and anyway, they’ll see the water inside and will know better than to try.”

“And there are no corkscrew-fish around, or any other potentially harmful wildlife?” I said.

“None that I can detect within a mile of our location at this moment.”

“Okay.” I pulled the mask over my eyes, nose, and mouth and switched the headlamp on.

“No headlamp,” said Aza, through the mask’s bone-conducting speaker. I nodded and switched it off, then hopped into the water.

The sea was lovely and warm, as always, reminiscent of a night swim in the Caribbean. I kicked out a little ways from the ship and looked back. The habitat’s interior lights illuminated the surrounding area, and its glass reflected the faint points of light emanating from the ship. I wondered if this would be the last time I’d be seeing it. I sincerely hoped not. We’d spent the better part of a year building that beautiful thing, and to abandon it in the eleventh hour would be devastating. I hoped whoever HE was didn’t have plans to destroy it.

I swam around the outside of the ship toward my quarters. I found my porthole and peered in to make sure it was the right one. There was poor Jody, sleeping the big sleep in my cot.

“Break the window using the chisel. I have already removed the oxygen from your quarters, so there won’t be an explosion when the air and hydrogen-saturated water mix.”

I would have said something snarky, but under the circumstances, said nothing.

I set to work. It was hard to get much force behind the hammer strikes in the water. At first I was worried the noise would bring people running, especially if it took me awhile to get through the window, but the window wasn’t glass, but some kind of multi-layered clear plastic that made a deadened sound when struck. After a minute or so of tapping at it, my tool pierced all the way through, and bubbles started glug-glugging out. It was too slow. I started on another hole. And another. Finally, after making five punctures in a line, the window cracked inward and a torrent of water and air moved in and out. I was blown backward for a moment, but it was soon calm again, with the room filled to the ceiling with water and the bubbles making their three-mile trip to the surface. As promised, there was no alarm yet. The rush of water might have woken some people up, but it was over so quickly I doubted they would bother to investigate.

“Let’s go to the secondary hab,” said Aza. “Turn slowly to your left until you see a tall spire shaped like an upside-down sock, thirty yards away or so. Swim to it.”

I turned. This part seemed risky. I had no way to find my position other than in terms of proximity to the habitat. The rebreather’s speaker could play a pinging sound that increased in pitch and frequency the closer the user got to the ship. We’d used that feature when first exploring the area. If worse came to worst, I could always swim back there, but that would fail the mission. I peered at the irregular white spires, which stretched away into the murk, punctuated here and there by tall clumps of black bottlebrush-like vegetation. I couldn’t see the edge of the massif in this direction, but it couldn’t be too far away. There–a spire that sort of fit Aza’s description, just at the edge of visibility. I headed slowly in that direction.

“After you’re there, turn on your headlamp and look around on the seafloor in a two-foot radius of the base of the spire for a small device attached to a cable. Then follow the cable in the direction going away from the ship, and you’ll run into the habitat.” Aza said this before I had reached the sock spire. She had no way of knowing where I was, and I had no way of replying to her. I had fallen off the edge of the map. I saw a gently waving basket coral to my left, sighted the sock spire and the habitat, and tried to memorize their positions relative to one another so I could retrace my steps if need be.

The sock spire was at the edge of where the habitat’s lights penetrated the murk. I switched on my headlamp, which seemed blinding in comparison. If someone looked out the window right now in my direction, they would definitely be able to see it. Maybe Aza could see it through one of the ship’s cameras. I did my best to keep the cone of light pointed toward the ground. The ground was littered with mini-spires, glommy white rock structures of all shapes and sizes that cast pitch-black shadows in the light of my headlamp. It would be very challenging to spot anything, which was probably the point.

I searched around the base of the spire. The device ended up being located on the side of the spire that was almost directly opposite the ship, which I guess made sense. It appeared to be a small camera that was pointed at the ship. I waved at it, knowing Aza could see me. The camera was approximately the same size and shape as one of the mini-spires, with a small white cable stretching away in the opposite direction. I swam slowly with my face inches from the ground, following the cable back to its origin. One time I bumped my head into a spire in front of me, which was pretty painful. I decreased my pace even further and made sure to look ahead of me at intervals.

I was swimming through absolute blackness save for my headlamp, which only pierced the gloom by about twenty feet in one direction. Eventually I reached the edge of the massif, a cliff from which I couldn’t see the bottom through the murk, so I could tell it was between twenty feet and three miles tall. The little cable continued over the edge. I followed it.

Thirty feet down, the cliff face opened up under me. It was a cave, extending back into the cliff. And there was the habitat!

It was situated in the top and rear of the cave, so its lights weren’t visible from above. It was small, and appeared to be made of spent fuel tanks from the ship, six truck-sized cylinders welded together haphazardly, with cables and tubes sticking off it in all directions. There were no windows.

As I approached, someone wearing a rebreather and fins swam downward from beneath the habitat, silhouetted against the lights. I drew in my breath. It looked like Arty! She was soon followed by the lanky shadow of Roscoe and the hulking one of Neil. They swam over to me. Neil arrived first and swept me into a crushing bear hug. Arty shook my hand vigorously, and Roscoe awkwardly gave me two thumbs up. It was hard to tell with the masks on, but I thought they looked a bit bedraggled. Their hair was longer–especially noticeable on Arty and Neil, who’d previously worn theirs extremely short–and Roscoe had a scraggly beard, while Neil had an impressively bushy one. I guessed they’d been unable to pack shaving equipment. We all headed back to the habitat together.

Arty, swimming ahead of me, made the hand sign for “watch out”–an extended arm with palm forward, like a crossing guard, followed by pointing at the threat. The threat turned out to be some sharp edges on the sheet metal surrounding their moon pool. A rough hole had been cut in the bottom of one of the fuel tanks and the edges crimped back using pliers, leaving some unfinished spots. We all hauled out of the moon pool into the habitat and took off our rebreathers. There was a faint bleach-like odor in the air. I looked at our surroundings. There was a rough-edged hole in each end of the cylinder and one in the middle, leading to the next tank. There were disorganized racks of diving equipment and tools on shelves along the walls, and an air handler. Everything was slightly angled, since the surface was rounded and there was no clear delineation between floor and wall.

“You made it!” said Arty, excitedly, her eyes glittering.

“Yeah,” I said, overwhelmed. “You’re alive!”

“Pretty soon we’ll be the only ones,” said Roscoe, darkly.

“Sorry, what? Aza didn’t explain anything to me yet,” I said. He filled me in.

Apparently we’d been fed lies from the start, and were actually building the sphere for a different group of people to come live in. Those people were led by a different artificial intelligence than Aza, a more powerful one—HIM—that could take over her systems in the sphere, shoehorning her back into the ship. Once the sphere was habitable–that is, next week–HE would command the dock to fling the ship out into space, to make room for the other group’s spaceship to take its place. Given the way Enceladus was oriented, our ship’s trajectory would be perpendicular to the plane of the solar system, ensuring that it would never encounter anything ever again, leading to the eventual starvation of the crew. Or maybe Aza would convince them all to go back into stasis in the hope that they’d be rescued by random chance sometime in the next million years, before the reactor and the stasis pods broke down. That was assuming HE wasn’t able to simply cut power, depressurize the ship’s atmosphere, or do one of many other actions that would instantly kill everyone.

“How do you know all this?” I asked, trying to organize my thoughts. “It sounds kind of paranoid.”

“Aza figured out the details, but it makes sense if you think about it,” said Arty. “First, the fact that we were kidnapped and basically press-ganged into servitude. Historically, people like that have not been the ones to inherit their masters’ wealth. Second–” she gestured to the fuel tank we were sitting in– “the ship doesn’t have enough fuel to return to Earth or go anywhere else. You could argue that’s because we’re supposed to stay and live here, but it seems like quite a risk to us. It makes more sense if you assume we’re supposed to be expendable, and expended. Third, we’re a bit of an odd choice for a founding population of an off-Earth colony. Have you been to the stasis bays, counted how many people we have here?”

I pictured the stasis bay, trying to ignore the lurch my stomach made when I pictured Jody’s waterlogged face. “There are two bays with maybe twenty pods in each?”

“Yeah. That’s way too few for a stable population. Plus, we couldn’t tell what kind of people the twenty that are still frozen are, but Aza can, and she says there are only two other women.” She paused, looked at me.

“If they were supposed to be the rest of the population of the colony, you’d expect nineteen women and one man, to balance us out,” I said. “Eighteen men and two women seems more like the cross-section of a group of construction workers. Like us. Backup crew, in case we had on the job casualties.”

Roscoe nodded, pleased I figured it out. “Another weird thing about our cohort is we’re all criminals of one stripe or another,” he said. “Not that that’s uncommon nowadays. But I’m wondering if it’s important to someone’s conscience that offing us is morally justified.”

That explained that, then. The narrower the specialization, the harder a time HE had finding a suitably sordid candidate. Hence Peter’s absurdly tiny transgression.

“Also, Aza can tell we’re being watched,” said Arty. “HE sometimes downloads stuff, though he tries to hide it. Trying to figure out how the project is progressing and how many of us are left.”

“Aza’s in the same boat as us,” Roscoe said. “If she let things proceed as planned, she’d be stranded in space with the crew for eternity. So I’m pretty sure our goals are aligned. We need to stop the newcomers from killing us. Whether that’s killing them first, or negotiating a truce, or begging for amnesty, depends on what kind of people they are. And what kind of people we are.”

“Can we save the rest of the crew?” I asked. “They don’t deserve to die like that. And it would put us in a better position if we had more people to stake a claim or make a threat to the newcomers.” My mental image of Arty getting shredded by a corkscrew-fish was replaced by that of Teddy, our youngest apprentice, with his eyes boiling in the vacuum of space.

“Aza doesn’t think so,” said Arty. “HE has set up his systems to be really air-tight. She wouldn’t be able to stop it if he decided to launch the ship, remove the atmosphere, whatever. Plus, HE will be expecting a certain number of people on board, and if there’s not that many, minus the reported ‘casualties’, he’ll go looking for us. We’d endanger ourselves plus the rest of the crew if we’re all in hiding together. Aza’s done everything she thinks she can get away with. Hand-picked our team with the people she thinks are the most effective and work the best together. Figured out all the resources that wouldn’t be missed and led us to bring them here. We’re as well-equipped now as we can be. But it’s still a pretty slim chance we’ll be able to pull it off. HE knows a lot about us and we know next to nothing about HIM and his people. We won’t know what we’re up against until they get here, and even then we’ll have to be very careful snooping around.”

She went silent. Everyone looked at each other bleakly. While it was great to be reunited–Aza had indeed picked the same people I would have–the news that everyone I knew would be killed in a week, most likely followed by ourselves shortly after, really put a damper on the mood.

“Wait a sec. What about Oliver?” I suddenly remembered. “Is he here too, somewhere?”

The three of them exchanged a glance among themselves. “No, he actually died,” said Roscoe. “The only real casualty of the project, as far as we know.”

That made me feel both worse and better. Obviously, any death was a tragedy, but Oliver had been one of the hardest crew members to get along with, so I was relieved to find out he hadn’t been picked for this coterie. Also, the extra safety measures I’d implemented hadn’t been completely unjustified.

That’s horrible, you just thought that you prefer Oliver dead than have to put up with him, some part of me complained.

I squashed that voice. Yeah, well, that’s the way it is. No point pretending to be sad about it. In all likelihood, we’ll all join him within the month, so what does it matter?

“Well, let’s get you some new clothes and give you the tour,” said Arty, briskly. We took off our fins and dried off, and I followed her through one of the ragged door-holes to see the new digs.

V. T+3.38 years

Early on the morning we were supposed to arrive, Uriel asked Paola and me to close the chicken coop with the chickens still inside it, and to leash the four cows to the wall. Then he summoned us all into the medical bay, in which all the equipment that had been there previously had been retracted into the ceiling or floor, leaving just the four cushioned exam chairs and a pile of what looked like straps on the floor. The straps were racecar-style cross harnesses, which could be hooked to the chairs. Through the windows, we could see that Saturn still looked the same–that is, impressively huge–but the moon was enormous. We were close.

When we were all gathered there, Uriel said, “Here is what is going to happen. First we will stop spinning. You will feel weightless. The counterweight will retract. Then we will descend to the surface. It will take about thirty minutes. The ride will involve small accelerations, no more than what you would experience in a car on Earth during normal operation.”

We all looked at each other. Paola was the first to ask a question. “Wait, so we’re landing on the counterweight?”

“We are landing with the counterweight pointing toward the planet, yes. But at no point will it be bearing our weight.”

“Oookay. And what happens once we get to the surface?”

“I will explain further once we are there. Please, everyone strap yourself into a chair.”

We climbed into the chairs and hooked the straps.

“If something goes pear-shaped, will oxygen masks drop from the ceiling?” Valerie joked.

“I am not anticipating anything that drastic, but yes, there are emergency respirators, and other emergency equipment, ready to deploy throughout this ship.”

“Well golly, that’s good to know. Thanks, Uriel,” she said, laughing.

“Everyone is strapped in. Prepare yourselves for weightlessness.”

Through the floor window, we saw the counterweight spewing propellant from a thruster on one side. Presumably our half of the ship was doing the same. I was gently pushed to one side of the chair, and at the same time felt like I was in an elevator that had started descending.

I was still in contact with the chair, but barely, restrained by the harness. I had a falling sensation in the pit of my stomach, which I always disliked on roller coasters. I tensed my abs to lessen the feeling, and hoped that the gravity on our new home would be sufficient to preclude me from having to flex for the rest of my life. Or that I would get used to it. Everyone else’s hair was floating into their faces. I was the only one with short hair. Paola quickly tied hers back with an elastic band from her wrist, but Dave and Valerie weren’t so prepared. I could faintly hear the livestock making a racket upstairs, and hoped they weren’t getting themselves dangerously tangled.

The moon stabilized in our view, taking up the entire window. I still couldn’t see any signs on the surface that anything had been prepared for us, but I could see some sort of geologic formation that looked like parallel-ish slashes. Visible through the front window, Saturn loomed majestically. The counterweight de-telescoped itself until it was almost out of view to our right, centered under the forest section of the ship.

“Here we go,” said Uriel. Our bodies tugged gently against the harnesses as we accelerated toward the planet. It grew, slowly; it didn’t feel like we were going very fast.

“Look,” said Paola, pointing. “A geyser.”

We were moving parallel to a thin trail of mist that was spraying out from the surface. As we descended, the mist trail got stronger and narrower, and we could see a few others like it in the distance.

“Geysers are hot, right?” I asked. Everyone else shrugged.

We descended further, and started to be able to make out what appeared to be the landing site. It looked like a deep, dark hole. Next to it was some kind of metallic structure.

“We’re going into that hole?” Valerie asked, as it became clearer that that’s what it was. “We don’t get to enjoy this ridiculous view of Saturn for more than a few minutes?”

“Once we land on the surface, we can pause if you like, to take in the view,” Uriel offered.

“No, no, let’s not delay,” she said impatiently.

Finally, we were pushed back down into our chairs at what felt like one gee as we started decelerating. We were landing in between two of the parallel slashes in the terrain, which turned out to be raised mountain ridges rather than grooved as I’d first thought. The metallic structure looked a lot like high-tech train tracks.

Slowly, the deceleration lifted, and at first I thought we were weightless again. But no, I was in fact sitting in the chair, but so lightly that any shifting of my weight propelled me upward, and it took a long time for me to settle back down. The gravity of this moon must be really minimal, substantially less than even Earth’s moon, based on the Apollo footage I remembered seeing.

The window in the floor looked straight down into the hole. It seemed bottomless.

“It’s snowing!” said Paola. I looked up, and saw she was right. Snow was drifting down in extreme slow motion, so slow that the movement was almost imperceptible. It was like time had stopped outside the ship.

There was a soft click, and Uriel said, “The ship is secured to the rails. We will begin the descent. It will take fifteen minutes.” A bright headlight turned on, illuminating further into the hole, but the bottom still wasn’t visible. We were pushed up against the harnesses again as we started moving down. Now our speed was apparent, as the ice walls were rocketing by. The very train-like ka-chunk of the rails was quite loud.

“Fifteen minutes at this pace?” Paola said disbelievingly. “This ice must be miles thick.”

“I’m down in a hole, I’m down in a hole,” Valerie sang in a folksy alto. “Down in a deep, dark hole.”

Dave joined in on a lower harmony. “I’m down in a hole, I’m down in a hole. Down in a deep, dark hole.” They repeated this phrase a few times, to the beat of the railroad noise in the background.

“What’s that?” I asked, once they had finished.

“The Miner’s Refrain,” said Valerie. “It just seemed appropriate.”

“It was very nice,” said Paola.

I agreed. “When we get there, we’ll have to get you two an instrument, and you can teach us something.”

“Dave plays electric guitar, and I play ukulele,” said Valerie. She pronounced it oo-koo-lay-lay. “We actually already have them in our closet in our quarters. But we haven’t been making much time for music lately, what with all the preparation.”

“But you must have played at some point during the past year and a half,” said Paola. “How did we never hear an electric guitar?”

“There is a layer of vacuum between the first and second floors for sound isolation,” said Uriel. “Anyway, I think you will have plenty of time for music after you arrive.”

We descended the rest of the way in silence. It really seemed like this deep, dark hole was never going to end. Finally, we started decelerating again. And then we saw it: the water.

“We’re a submarine?” exclaimed Paola. Uriel didn’t answer. The rest of us were just as dumbstruck. By the time we reached the water, the ship was moving very slowly, and we eased in with barely a splash. We accelerated again once fully submerged, but not close to the same blasting pace we’d sustained earlier.

“Do you think there are any aliens in here?” asked Dave.

“I don’t know. We could be moving through clouds of alien microbes and wouldn’t know it,” I said.

“Sure, but I’m hoping for some alien animals. Large, mobile living things.”

“I wouldn’t get your hopes up, but it’s possible,” I said. “Anyway, we’ll probably find out within the next few minutes.”

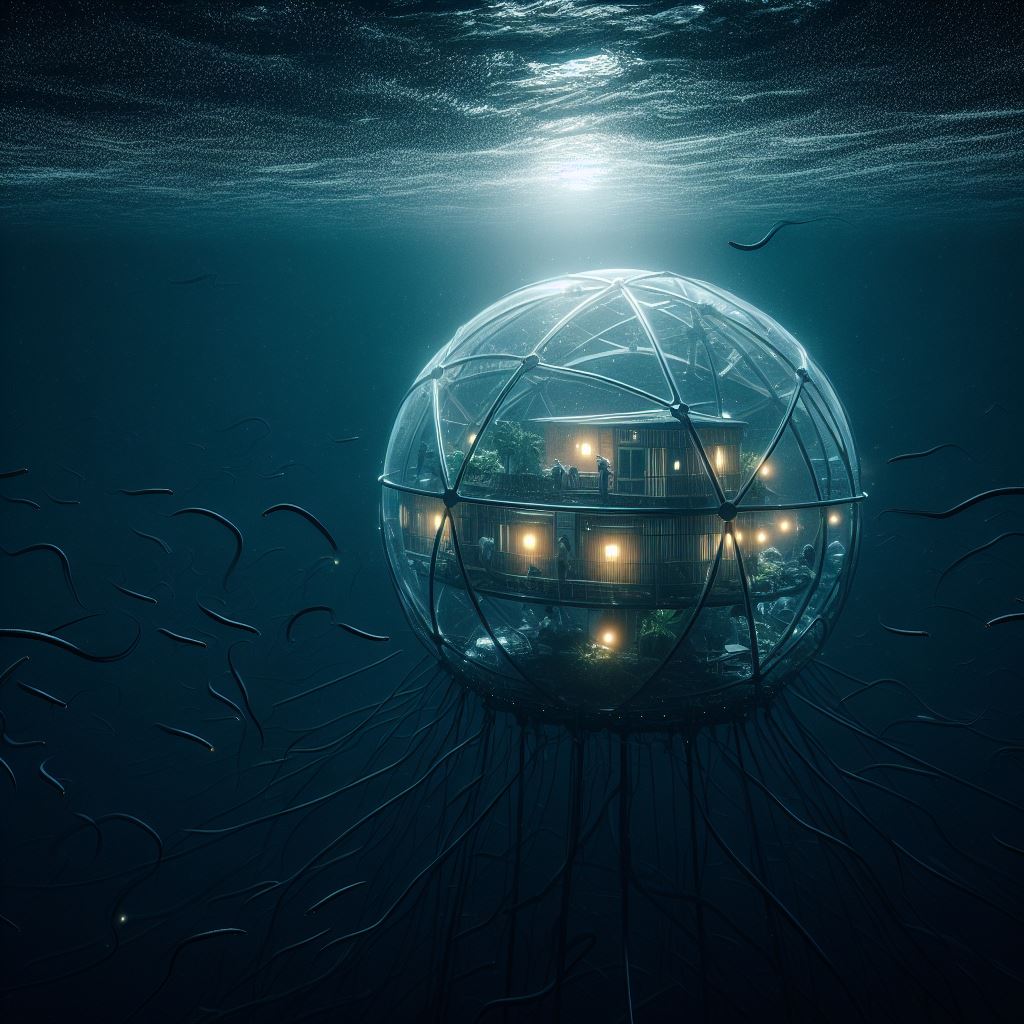

Finally, we could see light approaching up ahead through the murk. It resolved itself into the shape of a giant glowing basketball made of glass and steel. No, that’s not the right word–a geodesic sphere. There was a bright light at the top of the sphere, and on the underside it was held in place by a forest of thick steel cables anchored to the sea floor. The sea floor consisted of a collection of irregular white protrusions, like the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon, with copses of what looked like black brushy trees growing here and there. Life! The sphere was situated at the top of an undersea mesa, which dropped away to all sides. It was a breathtaking sight.

“Wow,” said Valerie, speaking for everyone.

We docked to the side of the habitat. In front of us, we could see that there were tall, spindly structures inside with platforms at various heights, and a few enclosed rooms, but otherwise it was quite empty. It was huge though–probably with a diameter at least twice the longest dimension of the ship. Plus, it had a lot more vertical square footage.

“We will now pressurize the ship and replace the nitrogen with helium,” said Uriel. “This will take ten minutes.”

“Hold up, that sounds dangerous,” said Paola.

“Based on your medical results, it should not be dangerous. Still, please tell me immediately if you experience any pain or trouble breathing. We are using helium because it’s more inert than nitrogen; at high pressures, nitrogen makes you drunk. Also, be aware that the inclusion of helium will have auditory effects.” We could already hear a hissing sound as the air was replaced. My ears felt pressurized, and I moved my jaw around to clear them.

“You mean chipmunk voice?” said Paola, already noticeably higher pitched than before. She clapped a hand over her mouth. “Oh my god, are we going to have chipmunk voice for the rest of our lives?” The phrase got higher and higher. I chuckled, also sounding chipmunky, which made me laugh more. Pretty soon everyone was giggling helplessly, sounding like a cast of cartoon characters.

“I think you will get used to it rather quickly,” said Uriel, also sounding affected.

“Wait! You don’t have vocal cords! Why is your voice like this too?” shrieked Paola.

“Solidarity,” said Uriel.

“Appreciated,” I said, laughing again.

“I’m down in a hole, I’m down–” Valerie started, but broke off, cackling wildly.

“I don’t know about ‘rather quickly’,” Dave said. “I think this is going to take some serious getting used to.”

Eventually, the hissing sound stopped, and the pressure in my ears stopped changing.

“Everyone all right in there? No discomfort?” asked Uriel.

I took stock. The air felt a little thick and took more effort to breathe than normal, but otherwise seemed fine. I looked around. Everyone was nodding. “All clear,” I said.

“I am opening the door to the habitat. Feel free to go out and explore. Watch your heads on the ceiling. Welcome to Enceladus.”

I unstrapped my harness and climbed carefully out of the chair. I was really almost floating–it felt as if I might be able to fly by treading air with my hands. I did a “flagpole” pose on the chair back, sticking my body out sideways like a circus performer. It was very easy. Paola jumped and turned a slow somersault in the air, but bumped softly into the ceiling, causing her trajectory to go out of control. “Ow,” she said, though it didn’t look like it had hurt.

“I’ll go release the animals,” I said. “The rest of you go ahead.” They nodded assent and bounced out into the forest, where it appeared the habitat was connected. I climbed up the ladder using only my hands and moon-walked unsteadily over to where we’d left the cows and chickens. They seemed spooked but none worse for the wear. I unhooked the leashes and opened the coop, then descended the ladder head-first just because I could. If this was the environment we’d be living in for the next few years, we would probably get used to some very strange modes of locomotion.

I bounced through the forest and out some enormous bay doors that hadn’t been there before, into our new home.