If you saw my previous post, you’ll know that I’ve been working on a science fiction novel that includes some elements of speculative evolution. Spec evo, as it’s known in the trade, consists of applying the universal rules of natural selection to create biologically plausible organisms, whether that’s the genetically engineered distant descendants of humans or Tarrasques or how a bat might evolve to a plunge-diving lifestyle. I’ve even done speculative evolution projects in a couple previous posts. In this post, I’ll go over the various types of aliens I created for the novel, how I came up with them, and why I made the design choices I did.

Note: If you saw my previous post, you know the level of drawing ability I’m natively capable of without using references. I wanted my protagonist, who’s supposed to have drawn these, to be a better artist than myself, so I asked DALL-E 3 to create various reference images for me of things like nautiluses and anemones and crinoids, chose the ones that fit my imagination, Photoshopped them together, and sketched over the result to produce the final images. One nice thing about using this approach to create aliens is that DALL-E is really bad at getting details right–for example, if I ask for a nautilus, it gives me a fanciful, spiky one that doesn’t exist in real life, so it ends up looking more alien.

This post contains some minor spoilers for my novel, which I’ll try to keep to a minimum.

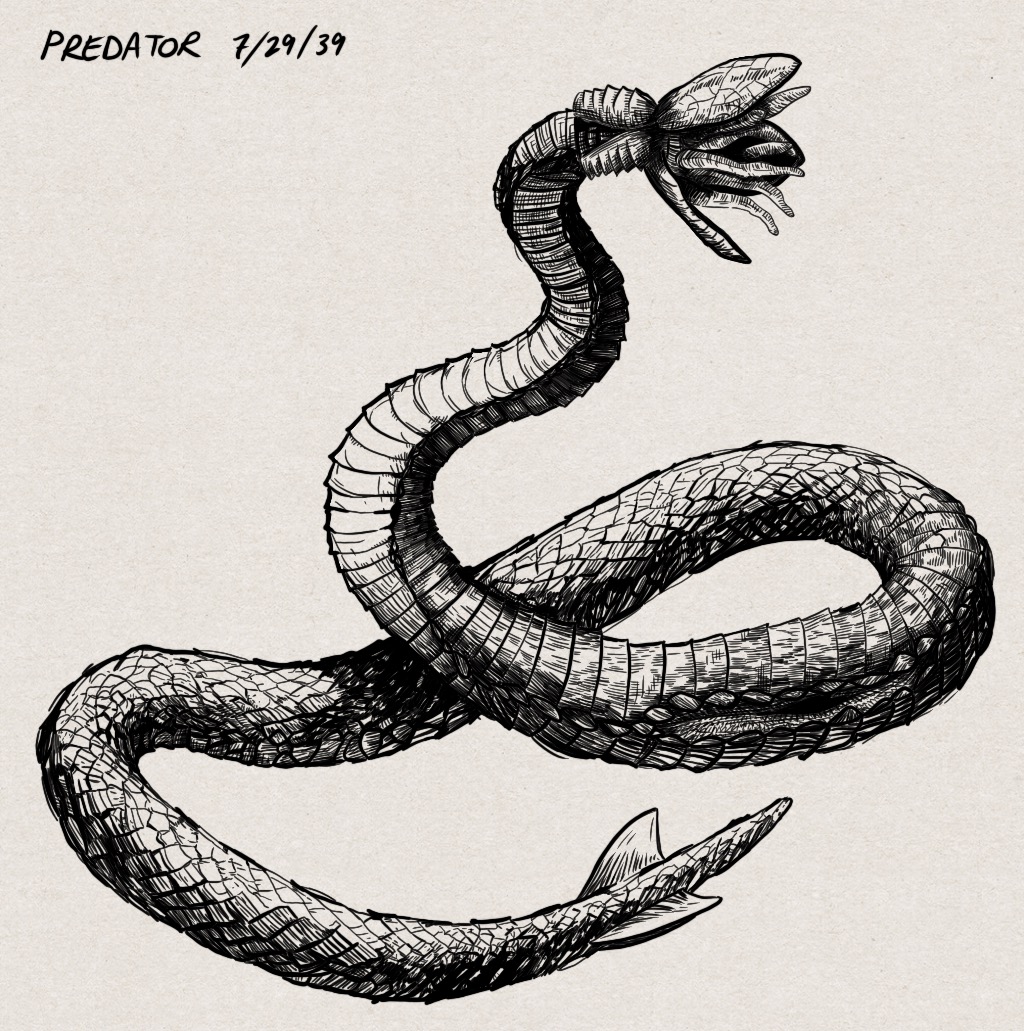

This was the first alien I designed, a macropredator. The way this one turned out drove the designs of all the rest of the aliens, because I wanted them all to be related, and be variants on the same basic bauplan.

I took inspiration for the general look from the headless dragons in The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (the one that carries you when playing the fruit minigame), the darklings described in the book series Midnighters, and Gore Magala from Monster Hunter. I wanted it to be sufficiently alien so as not to be a Rubber-Forehead Alien, but familiar enough to be empathetic and recognizable to the readers and the characters.

The predator has a rosette of sensory and manipulative tentacles on its front end, which can be protected by hard plates when it’s on the hunt. It has gill flaps, since gills are a simple and often convergently evolved design that provide a large surface area for gas exchange in the water. It breathes by pumping water in through a sphincter in the center of the tencales and out through the gills. Its brains are somewhere up near the tentacles as well.

Below the head, it has a long body covered in hard scales that in the predator, double as “teeth” for slicing and dicing prey items into swallowable pieces. The three mouths are located along the flanks. Why? Why not? Taste is not a very important sense to this animal, I guess.

It’s hard to tell from the picture, but this creature is supposed to be very large–around three feet in diameter and over sixty feet long. It is overall trilaterally symmetrical, and swims like a corkscrew, with its body looped about a central axis. Why? Three is the minimum to be radially symmetric, keeping the creature fairly simple and streamlined but also not bilateral, which is too familiar and Earthlike. Why the corkscrew? There’s a good reason for that, but we’ll get there later.

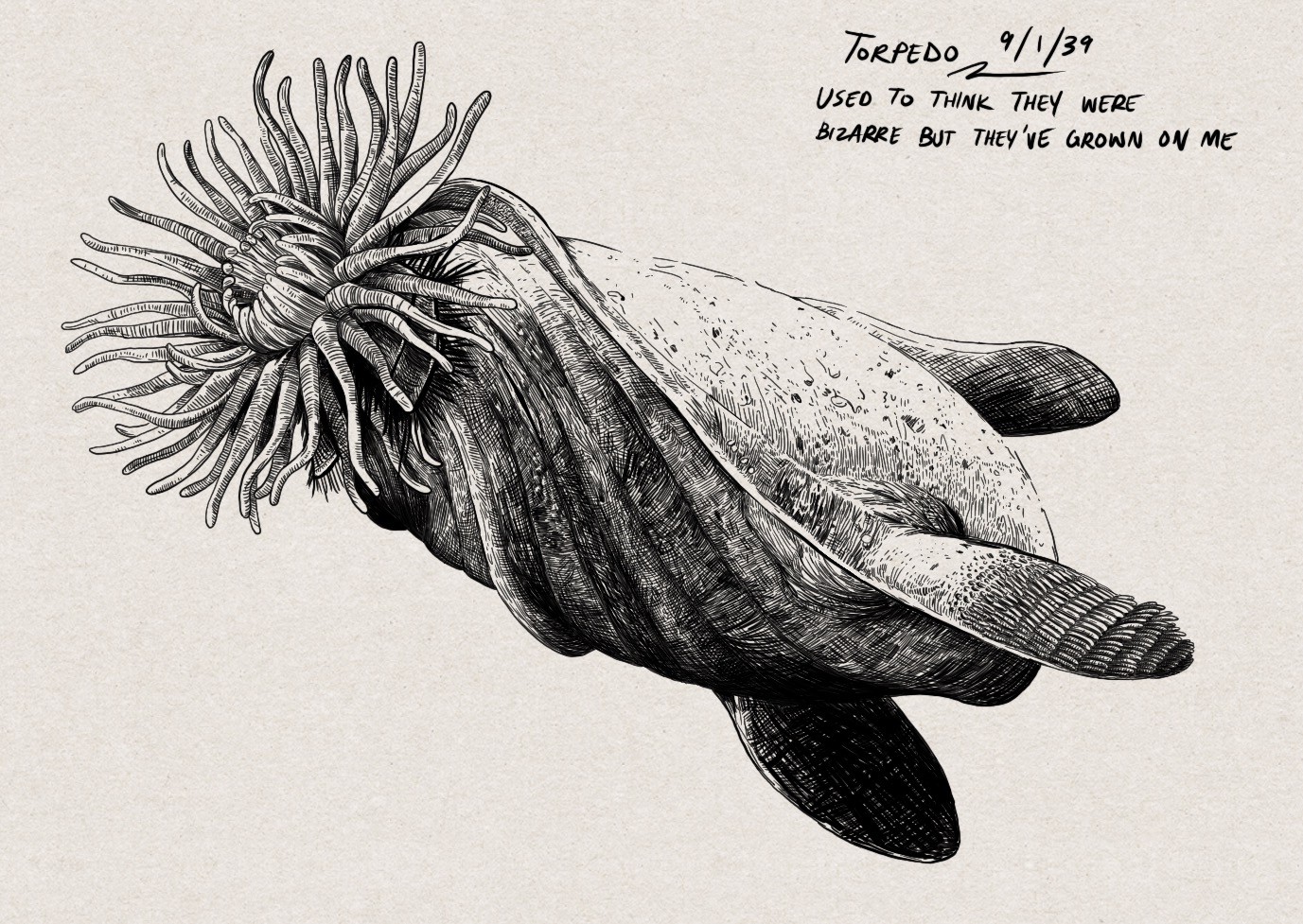

Here’s the second creature I designed, a macroherbivore. It shares the same basic body plan as the predator (trilaterally symmetric, tentacles, nose, and gills up front, three fins in back, mouths on flanks). Like most herbivores, it’s rotund in order to make enough space for a large fermenting gut inside. Herbivores need this because plants, being made of different stuff than animals, are harder to digest. Animals are already digesting themselves all the time, as part of bodily maintenance, so they already have the equipment needed to break down meat. Equipment to break down vegetable matter is extra, and often requires help from microbes.

While it doesn’t have armor over most of its body, it has some scales on the fins, which it can stand on end and rattle for communication, display, and defense purposes. Its tentacles are long enough to reach its flank mouths, so it feeds by pinching off autotroph parts (“leaves”) with its tentacles and passing them to the mouths, like putting things in its pockets.

This creature is supposed to be around four feet in diameter and eight feet long. Rather than being looped about a central axis, its body is twisted about its own long axis, so it swims by “screwing” through the water like a bolt. It can also “unscrew” and swim in reverse by rotating the opposite direction. Why? Again, I’ll get to that in the next section.

The creatures in the story live on Enceladus, a moon of Saturn sporting an undersea environment similar to the Lost City Hydrothermal Field in the Atlantic: a place where rocks reacting with water and carbon dioxide release methane and hydrogen, which on Earth are used as energy sources by microorganisms living there. These act as primary producers for the ecosystem, providing food for a community of crabs, clams, coral, worms, and other animals. While on Earth, there’s enough oxygen in the water for the animals to breathe, on Enceladus there is no source of free oxygen. As a result, my autotrophs (“plants”) are methanogenic, employing the reaction

\[CO_2 + 4H_2 \rightarrow CH_4 + 2H_2O\]while my heterotrophs (“animals”) are anaerobic methane oxidizers and/or general sulfate reducers, employing reactions like

\[CH_4 + SO_4^{2-} \rightarrow HCO_3^- + HS^- + H_2O\](the above represents a special case of sulfate reduction known as anaerobic methane oxidation).

The fact that they “breathe” methane means that their bodily fluids would probably be nonpolar and look something like crude oil.

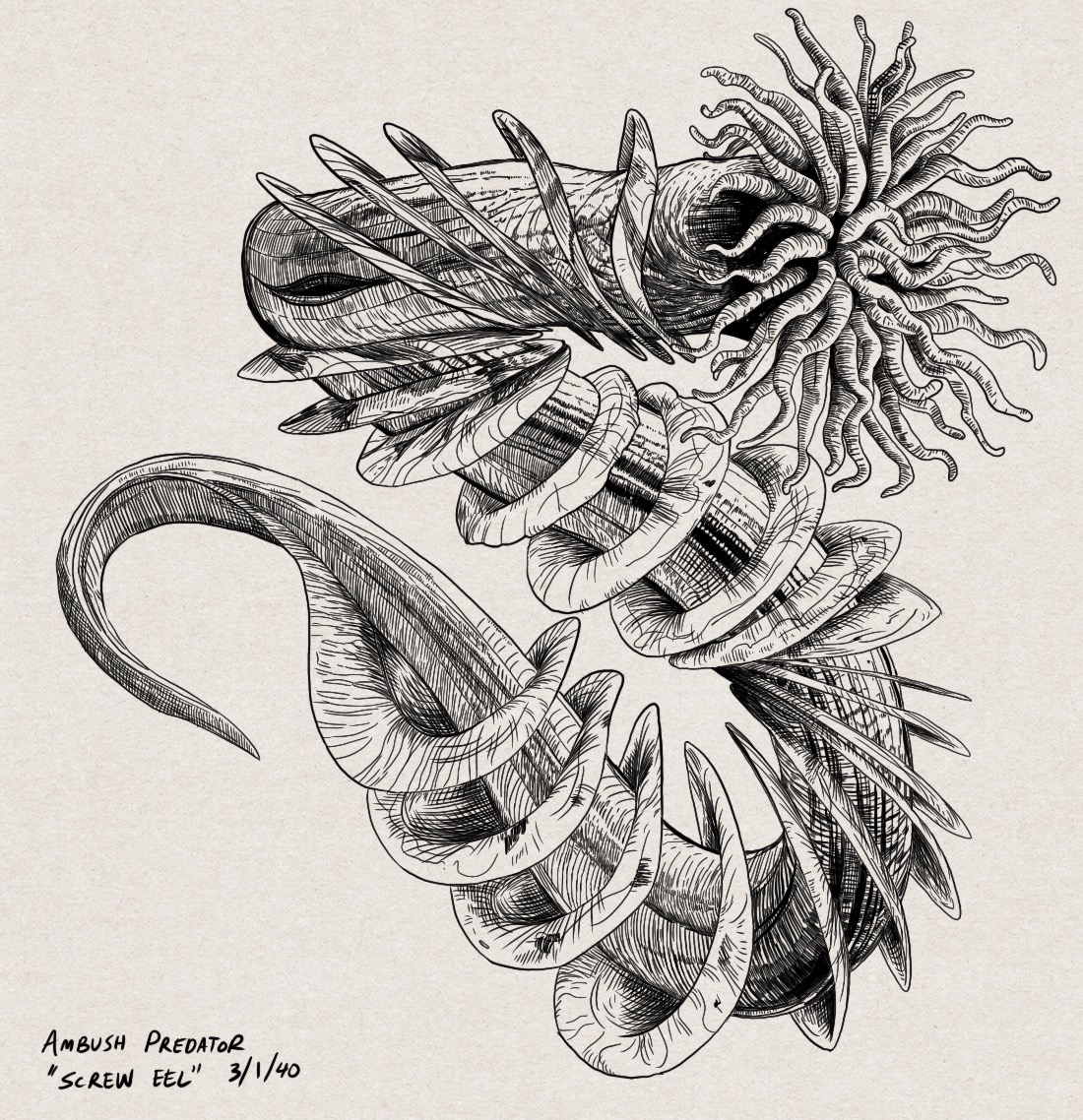

After designing the macropredator and macroherbivore, I asked myself, what would it look like if a creature had reduced or hypertrophic (overgrown) fins? How about reduced or hypertrophic tentacles? What niches might they fill? Here are some of the answers to those questions.

This is an ambush predator, a creature that lies in wait in a burrow or crevice and then screws itself out quickly to grab prey with its tentacles. It then excretes digestive juices to break it down if it’s too big, before twisting around and passing the prey item to its mouths. Since it lives in a burrow, it has reduced gills and fins other than the main spiral, so as not to snag on rocks and things.

None of the animals have eyes, because they live in total darkness under miles and miles of ice. Instead, they rely primarily on electrosense to navigate and communicate. This is something sharks, bees, and many fish on Earth can do. However, only a few fish, such as elephantfish and knifefish, can produce their own electric fields for high-resolution navigation and to send complex messages. The way electric fields work creates many strange knock-on effects on these fish’s behavior. I would highly recommend reading the chapter on electrosense in An Immense World by Ed Yong to get a sense for what it might feel like to be a knifefish. But in short, their range of “sight” is pretty narrow, since electric field strength drops off by a factor of eight for every doubling of distance, so it’s very energetically expensive to make a marginally stronger field. Therefore, they’re effectively swimming through thick fog all the time, and must be able to both (a) react to stimuli quickly relative to their movement speed and (b) maneuver themselves to keep the stimulus inside their electric radius or else they’d lose track of it. That means knifefish are really good at swimming backward as well as forward, and often do weird parallel parking maneuvers in order to keep track of objects, as a U-turn would temporarily put the object outside their sensable zone.

This is why my fish are often spirals: to make forward and backward swimming easy, and since they’re trilaterally symmetrical, it doesn’t matter to them which side ends up facing “up”.

This creature is supposed to be eel-sized, maybe three feet long.

This picture is the one that required the most drawing from imagination without reference, as I couldn’t get DALL-E to make a picture of a spiral fin, and couldn’t effectively photoshop other fins into this complex spiral shape. I’m overall happy with how it turned out, but there’s something wonky about the lack of shadows between the fins I don’t know how to fix.

This is a detritivore, which uses its armored, spiral fluted head plates to drill through the armor of dead animals to get at the goodies inside, which it consumes by excreting digestive juices and then sucking up the resulting goo. It has both reduced fins and reduced tentacles. It’s not great at swimming, mostly drifting with the current and hoping to land on a carcass, similarly to Earth’s bone worms. It’s worm-sized, so don’t be too afraid. It’s no Alaskan Bull Worm.

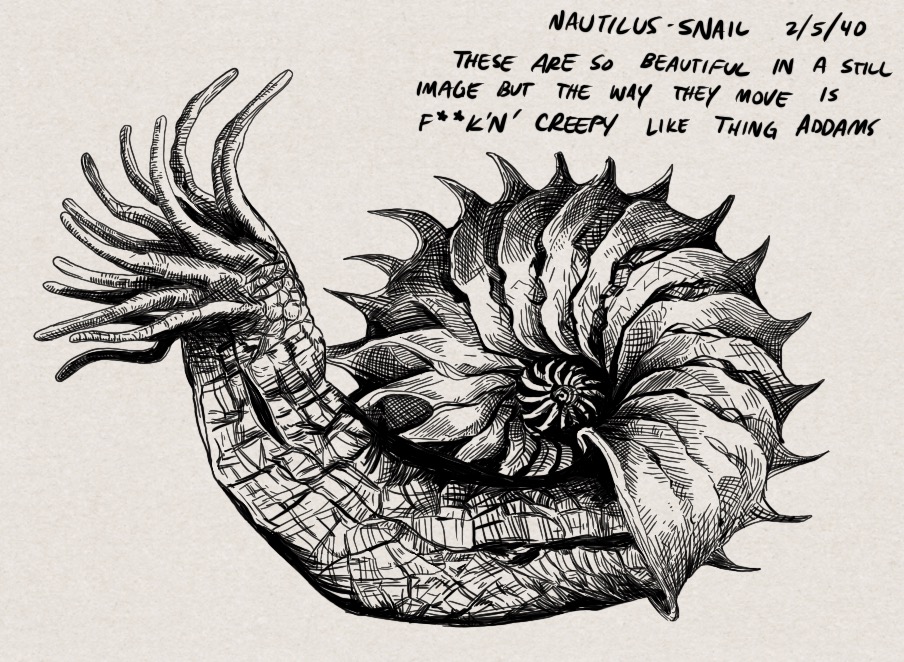

Still on the side of reduced tentacles and fins, here’s a heavily armored small critter. It feeds mostly in the same manner as the macroherbivore, and can retract into its shell for defense. While it looks like a snail, it doesn’t have a true top or bottom, so it moves more like an inchworm, or sometimes walking on the tentacles like a disembodied hand (since this moon has very low gravity).

Moving on to the opposite side of things, here’s a creature with hypertrophic tentacles and a reduced body. It can swim by flapping its tentacles in a similar awkward manner to a scallop or feather-star, but usually just sits or drifts around waiting for micro-prey to become stuck to its tentacles, which it then runs through its mouths to clean off.

In an even more simplified body plan, here’s a filter feeder that’s done away with mouths entirely. The body end is rooted to the substrate, and it’s gained the ability to absorb nutrients directly into its tentacles. While on Earth creatures that do this are considered more “primitive”, this one is “advanced” since it’s descended from free-swimming, active ancestors, and has developed new adaptations to this unusual lifestyle.

Wait–is that a bilaterally symmetrical animal I see? No! It’s a highly derived trilateral, asymmetric organism. Like a flounder, it has adapted to a flat lifestyle by messing with its ancestors’ symmetry, in this case flattening out the three sections to look a lot like a trilobite, twisting the floret of tentacles up to the top of the body, increasing the size of two of the fins to form “pectoral” fins while reducing the third “dorsal” fin and moving them all up closer to the head, and reducing the two side mouths in favor of one central mouth, and doing the opposite with the gills. It then swims by undulating its body up and down, like a flounder or a mammal, usually remaining buried in the sand while it waits for prey to swim near.

This flat lifestyle gave rise to other descendants who left that niche and found others, like…

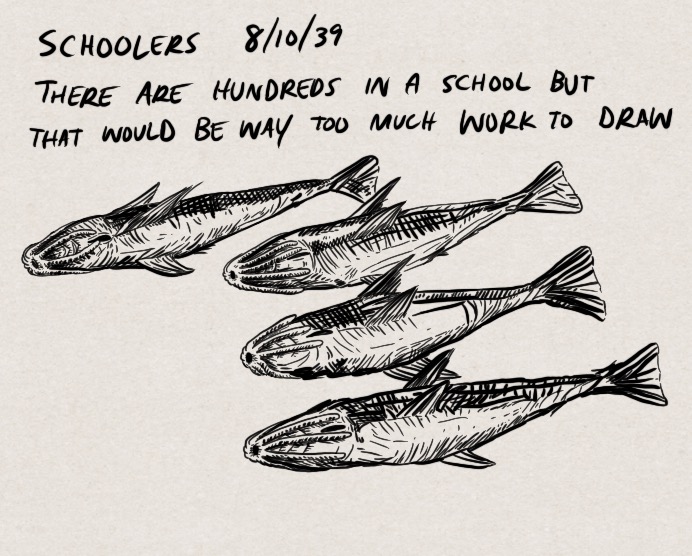

Small schooling fish, like anchovies turned sideways. Descended from a benthic ancestor, in order to become pelagic they reduced their armor and streamlined their bodies, secondarily increasing the size of the dorsal fin again and widening the end of the body to form a serviceable tail fluke. They live in large schools that stick together and communicate using electric fields, and eat small prey such as larvae and plankton. They will also scavenge if the opportunity arises. The existence of schools of critters implies the existence of predators that specialize on scooping them up, like thresher (bullwhip-tailed) sharks, dolphins, and whales do on Earth. But my characters never encounter such a thing, so that’s a project for next time.

All the aliens I designed, other than the “plants”, share the same body plan because (Watsonianally) they’re all descended from a complex common ancestor, which implies an evolutionary bottleneck at some point in this moon’s history. Many animal forms arose, but there was an extinction event that killed off all but this particular shape of organism, which then re-radiated, bending and stretching its body plan into diverse shapes to fill empty niches. From a Doylist perspective, I wanted to fully explore this one concept and give the organisms a sense of cohesiveness rather than baffling the reader with a plethora of different alien concepts.

Hope you found this exercise interesting and informative! There’s a lot of background research and knowledge that goes into making convincing, biologically plausible aliens. I really appreciate how natural selection is, as far as we can tell, a truly universal mechanism. There are a lot of really interesting, rigorous fields one can spend a lot of time studying, such as economics, psychology, and Earth history, that completely break down once you leave the conditions we have here. While some rules of economics and psychology might apply to aliens and alien societies, many wouldn’t because they happen due to quirks of how human brains work, and the systematic errors they’re prone to. But natural selection (and physics, chemistry, and game theory) apply everywhere, at least in this universe and the level-1 multiverse. That doesn’t make other fields not worth studying, but it’s just kind of cool to think about, and it’s necessary to keep straight which are which when speculating about conditions elsewhere.