Another out-of-left-field post this month. My office has a ping-pong table and a ping-pong internal chat group, but the usage has been fairly low and the chat group not very active. I wanted to revitalize the ping-pong community by organizing a tournament! But there were 50 people in the ping-pong chat room, definitely too many for everyone to play on the single table in one night. So, I put together a fancy spreadsheet to collect data on games people played during the workdays leading up to the tournament with the goal of enabling me to sort people into brackets in advance and set up only a few exciting, close matches for the day of.

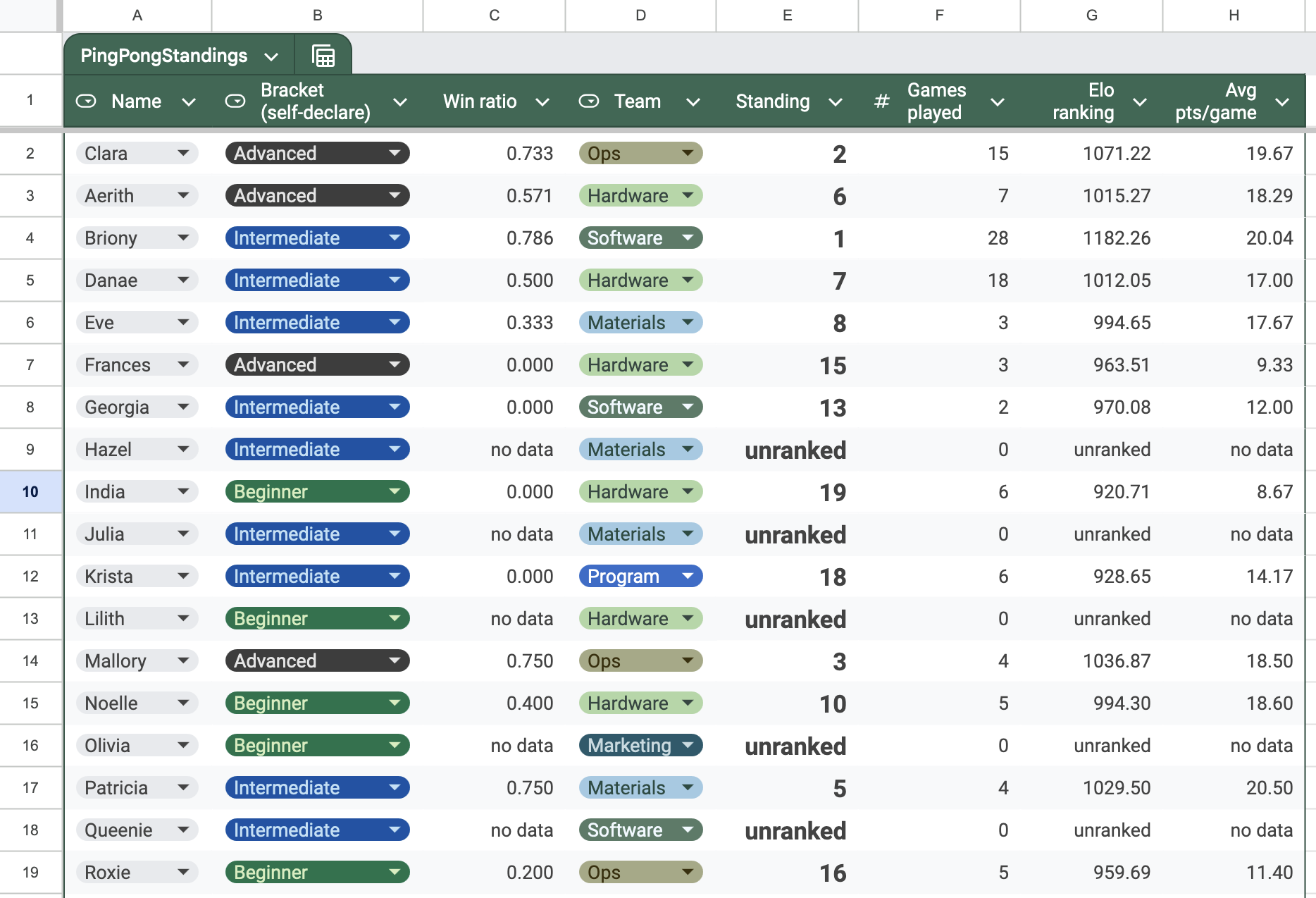

I went a little overboard on the functionality of the spreadsheet. Not only does it keep track of wins and losses, but it calculates the average number of points you earn per game, your win ratio, your Elo standing, and your rank.

What is Elo?

The Elo rating system is named after Arpad Elo, a physics professor and chess player. It’s a point-earning system for two-player games that awards some number of points to the winner and detracts the same number of points from the loser. The number of points awarded and lost is determined by the differential between the two players’ Elo scores before the game. If Aerith is really good and has a high Elo to start, and Briony is really bad and has a low Elo, you would expect Aerith to win against Briony. If that ends up happening, Aerith wins a very small number of points and Briony loses a small number. But if Briony manages to win against Aerith in a big upset, Briony will win a lot of points and Aerith will lose a lot.

Over the course of many games, players’ ranks tend to stabilize at a level that represents their actual skill. However, Elo doesn’t take into account how many games a player has played. So against new players, whose scores have not yet found their homes, older players can erroneously win or lose a lot of points. Other scoring systems mitigate this by having your score become harder to change the more games you’ve played. But Elo is still widely employed and is plenty complicated for my personal use case.

Okay, here’s the math. First, we want to calculate how likely it is that Aerith wins, and how likely it is that Briony wins, based on their current scores. Let’s say Aerith has a slight edge over Briony to start; her rating is 1050 while Briony’s is 950.*

*Note: it’s common practice for new players’ Elo ratings to start at 1000. Some implementations don’t let players drop below 1000, which makes it a nonzero-sum game; you can win points that are not lost. But I didn’t do it that way. Every time you win a point, someone else has to lose a point.

Let Aerith’s starting score be \(A\) and Briony’s be \(B\). Then the probability of an Aerith win, \(E_A\), is equal to

\[E_A=\frac{10^{A/400}}{10^{A/400}+10^{B/400}}\]Which in this case is equal to 0.64, or 64%. Where did the 10 and the 400 come from? It’s just a way of translating scores that are easy to look at, like 950, into probabilities. You could use the transformed score \(10^{A/400}\) instead, but it would be less clean-looking.

If Aerith didn’t win, Briony must have won, so \(E_{\text{winner}}\) is always equal to \(1-E_{\text{loser}}\).

The number of points won or lost at the end of the match is equal to

\[K(E_{loser})\]Where \(K\) is a sensitivity factor that you can choose. In chess, they traditionally use \(K=32\), but if you want scores to be more volatile you could choose a larger \(K\), and if you want them to be more stable you could choose a smaller one. I’m just using 32 because I don’t have an opinion and figured the chess people probably know what they’re doing.

Note that the maximum number of points that can be won or lost is equal to \(K\). If Aerith has a 100% chance of winning against Briony, but Aerith loses, her score will decrease by \(K\) points and Briony’s will increase by \(K\) points. If Eve and Mallory are evenly matched (each has a 50% chance of winning), whoever wins will gain \(\frac{K}{2}\) points and whoever loses will lose that many points. If Aerith has a 100% chance of winning against Briony and does in fact win, she will gain no points.

Implementing Elo in Google Sheets: Overview

First, let’s take a look at the end result, so we can know what we’re driving at. Here’s an anonymized version of the spreadsheet itself, if you want to click around and take a look at the formulae: Elo Calculator

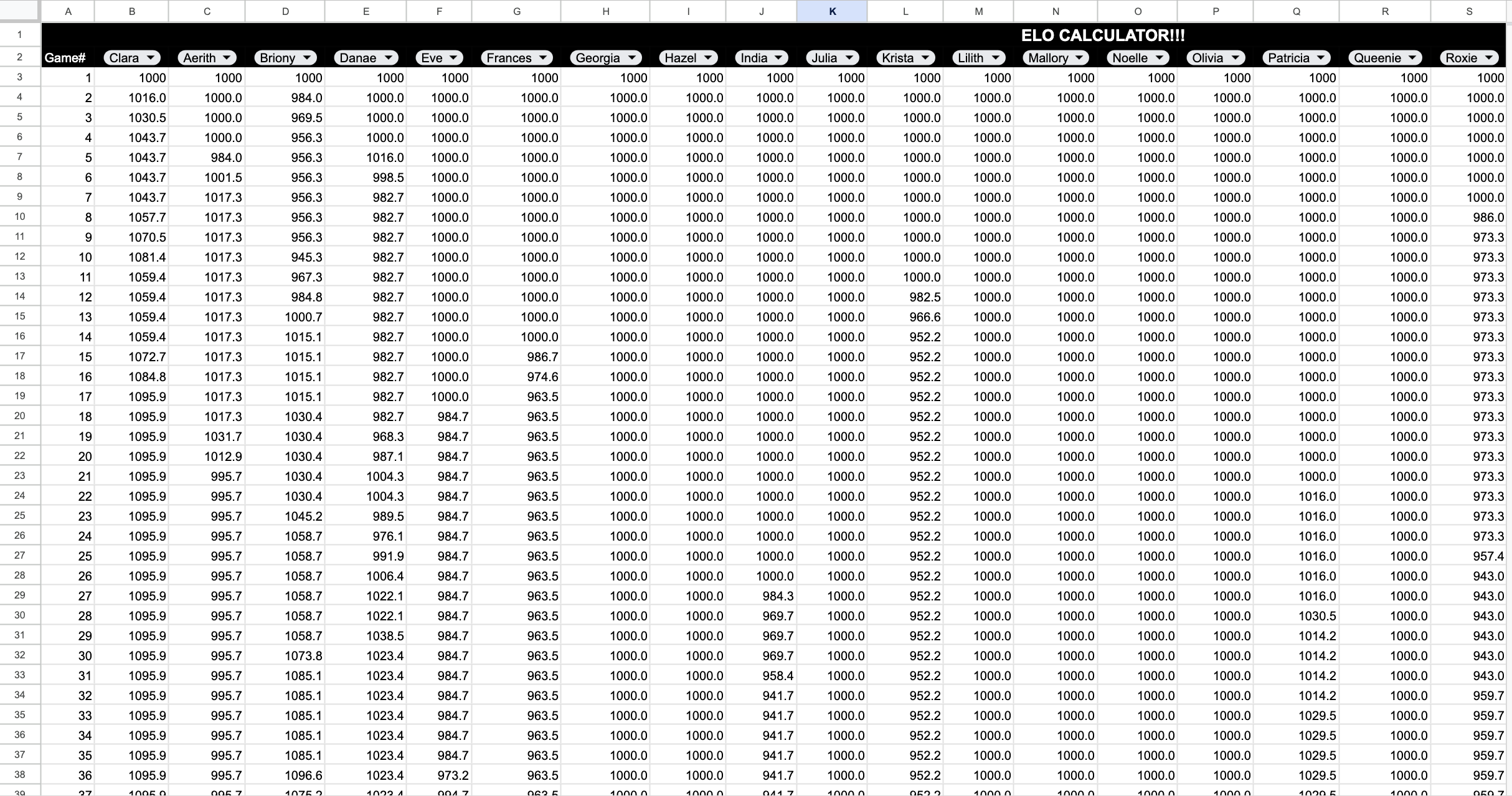

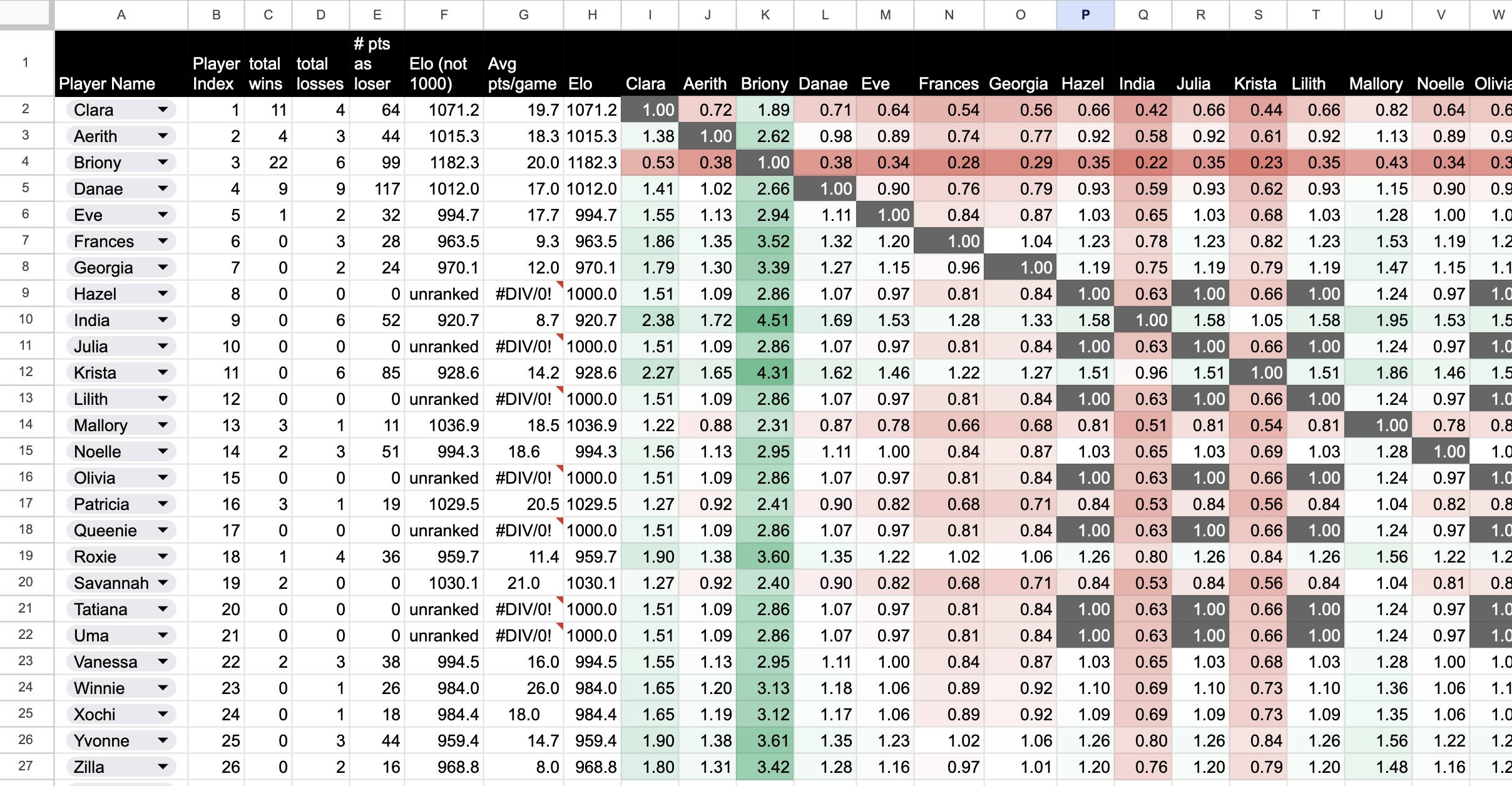

If you don’t want to click mysterious links on the internet, here’s what the front page of my spreadsheet looks like.

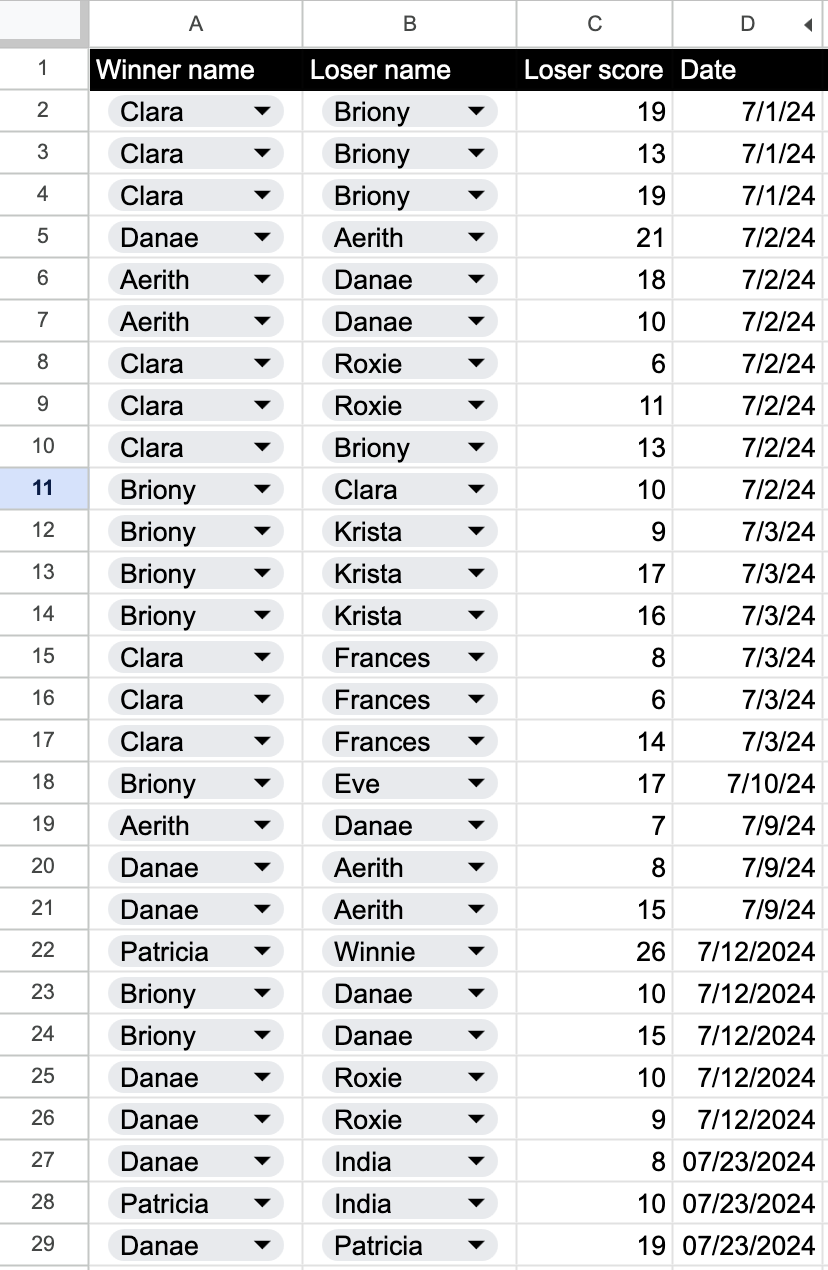

Here’s what the log where people enter their games looks like:

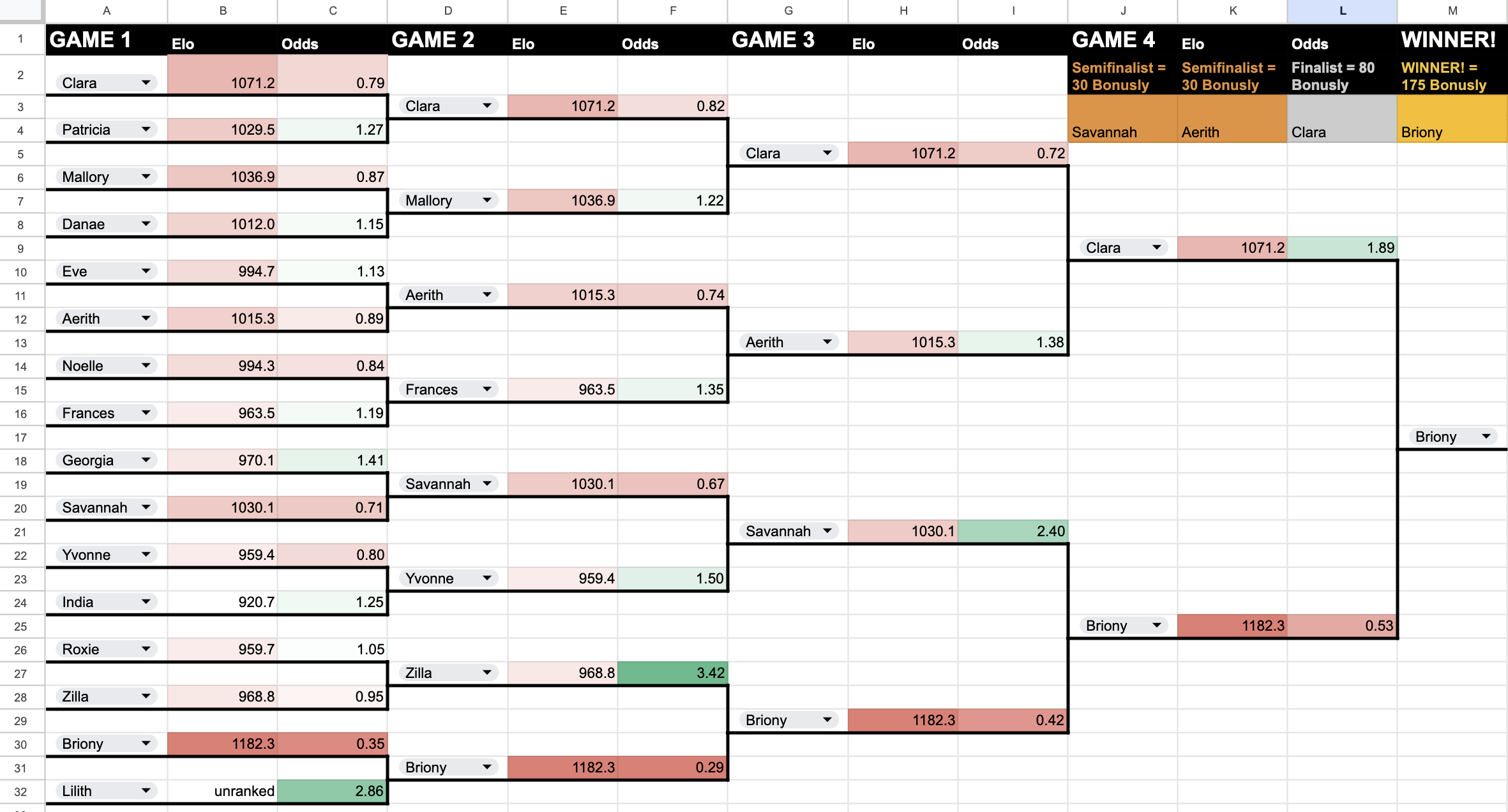

And here’s the bracket I made for the tournament!

Let’s jump right into how I made Elo work!

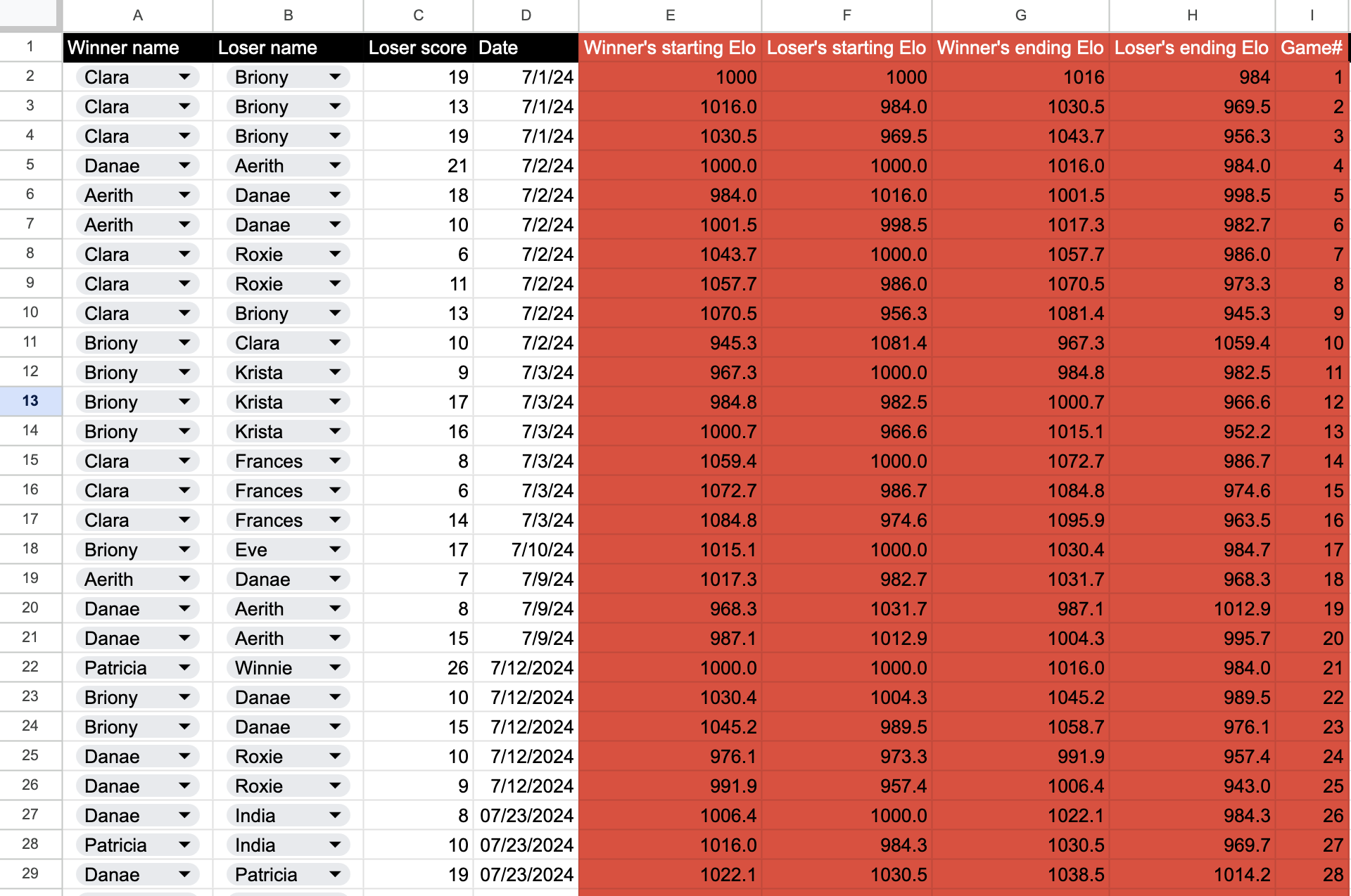

First, there are some secret columns on the Games tab that do some game-by-game calculating. These are normally kept hidden.

As you can see, every game, the winner’s and loser’s starting Elos are somehow looked up. Then the Elo formula is applied to them in columns G and H to get out the modified scores. And column I is just a game counter, needed to perform the lookups. We’ll come back to how exactly the lookups work in a minute.

Here’s a completely hidden tab that stores everyone’s Elo scores, called “Magic”:

Essentially what’s happening is, every game, the Games tab looks up the person’s name according to what’s entered in the “winner” and “loser” cells, finds in this big table the score corresponding to the current game counter, performs the Elo update on both scores, and stores them back in the next row of this table.

The unfortunate thing is, I couldn’t think of a way to do this calculation only on the scores of people who actually played. Every game, everyone’s Elo is recalculated, even if they were not involved.

To calculate the other stats (win ratio, number of games played, average points earned per game), to calculate betting odds, and to clean up the “divide by zero” errors, I also created this tab, called “Stats”:

Implementing Elo in Google Sheets: Nitty Gritty

Okay, if you’re still interested, let’s look at what’s actually happening in each cell, starting with the lowest-level / most interior of the parentheses in the calculation and working our way outward to the top-level outputs.

Do the math

First, let’s look at the math happening in the Games tab, still ignoring the lookups for now. Here’s what’s in cell G2, or the first “winner’s ending Elo” value:

=E2+32*(1-((10^(E2/400)/(10^(E2/400)+10^(F2/400)))))

E2 contains the winner’s starting Elo, or \(C\) in this case, and F2 contains the loser’s starting Elo, or \(B\). This formula is just doing the Elo calculation above in a single step: new score equals old score plus \(K\) (equal to 32) times one minus the probability that the winner would win (equivalent to the probability that the loser would win).

The loser’s new score in H2 is very similar:

=F2+32*(0-(10^(F2/400)/(10^(F2/400)+10^(E2/400))))

But the E’s and F’s are reversed, and the points are subtracted instead of added. Then I dragged these formulae all the way down columns G and H.

Update Elos

Now let’s go to the Elo table. Everyone’s score just starts as 1000, that’s the top row. For every row after that, the cell uses the IFS (if-else) function to determine if the player in that column was involved in the game, and update their score if they were. Here’s what IFS does:

IFS(condition1,value_if_1_true,condition2,value_if_2_true,condition3,value_if_3_true)

It returns the value corresponding to the first true condition it runs into. If none of the conditions are true, it returns #N/A.

Here’s what’s in cell B4:

=IFS(Games!$A2=B$2,Games!$G2,Games!$B2=B$2,Games!$H2,1=1,B3)

This is what it’s looking for, step by step.

- If the name of the winner of the game corresponding to this row’s counter matches the name at the top of this column, return the winner’s new score.

- Else, if the name of the loser of the game corresponding to this row’s counter matches the name at the top of this column, return the loser’s new score.

- Else, if \(1=1\) (an always-true statement), return the same score as the cell above, since this player was not involved.

The dollar signs mean “hold” the value of this row or column when dragging a formula across an array of cells. So the dollar sign in the first term makes it so that even when you drag the formula downward, the cell will still check against the name at the very top. And the dollar sign in the second term means that even when you drag the formula to the right, the cell will still output the score in the “winner’s new score” column rather than one of the irrelevant or blank columns to the right of it. So I entered this formula in cell B4 and then dragged it across to column AA and all the way down.

Look up starting Elos

Now we’re ready to look at the lookups back on the Games tab, which are getting the players’ starting scores. Here’s what’s in cell E2:

=HLOOKUP(A2,Magic!$B$2:$AA$407,1+I2,FALSE)

What does HLOOKUP do? It stands for “horizontal lookup”, and it searches across a row for a key string, and when it finds it, goes down that column a certain number of cells and returns the value there. Here are the arguments it takes:

HLOOKUP(key_string, target_range, index, is_sorted?)

So in the case of cell E2, the key string it’s looking for in the Elo table is the value in A2, which is the winner’s name. The range it’s searching across is the whole Elo table, which is the same for every cell, hence the dollar signs on every term. The index, or number of rows it should count down until it reaches the target value, is equal to one plus the current game counter, since we have to start one past the title row and then proceed down the column until we reach the value corresponding to the current game. For some reason you have to tell HLOOKUP if the range is sorted or not, probably because it can compute more efficiently if it is. My range is not sorted, so the last argument is FALSE.

Similarly, here’s what’s in cell F2, or loser’s starting score:

=HLOOKUP(B2,Magic!$B$2:$AA$407,1+I2,FALSE)

Everything is the same except the key string is now the loser’s name. I dragged these two formulae all the way down columns E and F.

Get latest Elo

Now we have the scores calculating for each game. How do we look up the latest one to report on the front page? Another HLOOKUP. The way I did this took multiple steps, but I could’ve done it in a single step; but I’ll just explain what I actually did. Here’s what’s in cell G2 on the Stats tab, which returns the player’s current Elo:

=HLOOKUP(A2,Magic!$B$2:$AA$408,407,FALSE)

The key string is the player’s name, the range is again the whole Elo table, the index is a random large-ish value, and the range is again not sorted.

*Since there’s no function for “get last value in an unbounded range” in Sheets, I just chose a large value to represent the latest score, i.e. 407 in this case. That means when we play more than 407 games I’ll need to expand the spreadsheet.

Evaluate standings and cleanup

This is fine, but I wanted standings, and didn’t want to penalize people for having an Elo less than the starting value / reward people for not playing. So I used IF to change the rating of anyone whose Elo is exactly 1000 to the word “unranked”. IF takes the arguments (condition, value_if_true, value_if_false). Here’s what’s in cell E2:

=IF(G2<>1000,G2,"unranked")

To count the player’s total wins, I used COUNTIF, which takes the arguments (range, key_string). This is what’s in cell B2:

=COUNTIF(Games!A:A,A2)

So it’s searching the entire “winner’s name” column, looking for the name of the player in this row, and returning the total number of times this player’s name showed up in that column. Similarly, to find the total number of losses, cell C2 contains

=COUNTIF(Games!B:B,A2)

It searches the whole “loser’s name” column on the Games tab looking for the name of the player in this row and returns the total number of times this player’s name appeared there.

Now let’s go back to the front page, where we have a column for “games played”. Here’s what’s in F2:

=Stats!B2+Stats!C2

Hopefully that was obvious.

Now we can apply RANK.EQ to output standings on the front page! These are the arguments it takes: (value, range). And here’s what’s in cell E2:

=IF(F2=0,"unranked",RANK.EQ(Stats!E2,Stats!$E$2:$E$27))

So if the player has played no games, this cell shows the word “unranked”; otherwise, it returns the ranking of this player’s Elo relative to everyone else’s.

Implementing Betting Odds

The purpose of all this data collection and processing was to seed a maximally exciting tournament bracket! In addition to Elo, I wanted people to be able to place bets on any individual game, and to do that, I needed betting odds. Those only depend on the probability of winning or losing a given matchup, which we already calculated as part of Elo. So this should be easy!

The odds table

The right side of my stats tab is taken up by a table of odds values. Let’s take a look at what’s in cell J2, which is what you would win if you bet $1 on me (Clara) beating Aerith:

=(10^(VLOOKUP(J$1,$A$2:$H$27,8,FALSE)/400)/(10^($H2/400)+10^(VLOOKUP(J$1,$A$2:$H$27,8,FALSE)/400)))/(1-10^(VLOOKUP(J$1,$A$2:$H$27,8,FALSE)/400)/(10^($H2/400)+10^(VLOOKUP(J$1,$A$2:$H$27,8,FALSE)/400)))

Holy cow, what is that monster of a formula? Didn’t I say this would be easy? Well… let’s break it down, from the inside out.

First, you’ll notice that one term is called four times: whenever VLOOKUP appears, it has the same arguments. So let’s start there. What is this looking up?

J1 contains Aerith’s name, and the range A2:H27 contains everyone’s names and Elo scores, in which the Elo scores are 8 cells away from the names. So this term is looking up Aerith’s Elo score (let’s call it \(A\)). And the other term this function is calling is H2, which contains my Elo score (let’s call it \(C\)).

Next, the math. Here’s the formula rewritten in a nicer format:

\[O_C=\frac{\frac{10^{A/400}}{10^{C/400}+10^{A/400}}}{1-\frac{10^{A/400}}{10^{C/400}+10^{A/400}}}\]Again, you can see a term recurring: the probability of an Aerith win. Let’s call that \(E_{loss}\), since we’re calculating the betting odds on me.

\[O_C=\frac{E_{loss}}{1-E_{loss}}\]Now we can finally see what’s really happening here. If \(E_{loss}\) is 50%, then the odds will be equal to 1: if you bet a dollar, you stand to win or lose a dollar. If \(E_{loss}\) is 10%, that is, you’re betting on the favorite, the odds will be equal to \(\frac{1}{9}\), so if you bet $1 you’d only end up with $1.11 for winning that bet.

The dollar signs and lookups make it so that we can drag this formula all the way across and down to populate the whole odds table. I added some nice conditional formatting to indicate when there were even odds (or if someone was playing themself) and when the odds were good or bad.

Populate brackets

We can use lots of VLOOKUP (vertical lookup) to pull values from the stats tab, including the odds table, and stick them into the bracket tab. This is fairly straightforward except for the odds lookup, since it’s nested: one VLOOKUP uses another one as its index. This is what’s in cell C2:

=VLOOKUP(A2,Stats!$A$2:$AH$27,VLOOKUP(A4,Stats!$A$2:$B$27,2,FALSE)+8,FALSE)

The outer VLOOKUP is looking for the name at the left in the entire stats sheet. The inner one is looking up the opponent’s name just in the left two columns of the stats sheet and returning that player’s index number. That tells the outer VLOOKUP how far to move over in the odds table to find the correct opponent. The “+8” term is to move the counter past all the non-odds-table stuff on the left.

And that’s basically it! I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to figure out how all the other bells and whistles work. Hope this helps you if you’re trying to implement your own competitive rating system and aren’t a software engineer. Happy Eloing!