And now for something completely different…

As I mentioned in my post about speculative evolution, some fields of study are universally applicable, like physics, chemistry, and evolution, while others, like economics and psychology, are not generalizable. Music theory is an extreme case of the latter: it was made up to explain music that had already been created, which didn’t follow any consistent rules; when you ask “why” enough times, the root reason is usually “it just sounds good”. As a result, there are numerous exceptions to rules, unexplainable phenomena, and unnotateable sounds that stymie music theorists’ attempts to categorize things neatly.

On the flip side, music theory generates a lot of new hypotheses to explore, which might not have occurred to anyone if the math and conventions of notation didn’t beg the question. It’s like how Einsteinian relativity implies the existence of black holes and white holes.

Apologies in advance for the rotated videos… I’m a Youtube newb.

A Brief History (and Physics) Lesson

The ancient Greeks were the first to really study music (at least, the first to compile a significant body of research on it). They understood harmonics from a physics perspective and based much of their music on dividing strings or resonating pipes into mathematically equal lengths.

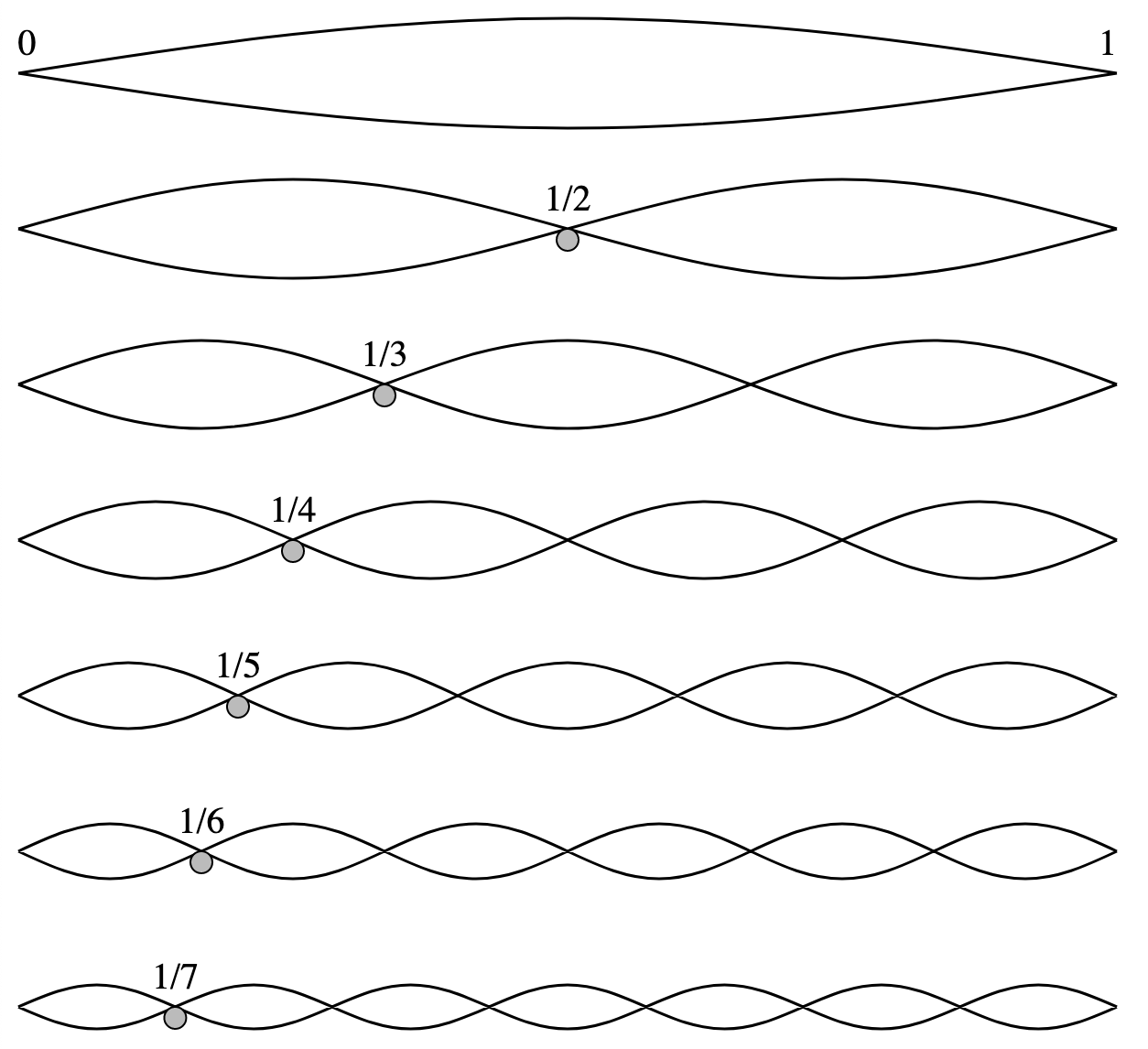

If you pluck a guitar (or lute, or lyre) string, then put your finger in the exact middle and pluck one of the halves and compare the two tones, they will be an octave apart. On a keyboard, that’s the difference between one named letter note and the next–C4 to C5, for example. This is called the first harmonic.

If you then put your finger exactly a third of the way along the string and pluck the small side, the tone will be a perfect fifth above the first harmonic; the third harmonic will be a perfect fourth above that, the fourth harmonic will be a major third above that, and the fifth harmonic will be a minor third above that. (Ignore the etymology of those intervals for now; just know that it’s the physics of a vibrating string that defines them.) After that, the intervals get a bit wonky and start to sound bad. But it also starts to get a bit impractical to divide a string that much, so it didn’t really matter.

In the Middle Ages, people started to invent newfangled instruments like the harpsichord and clavichord, which employed a keyboard instead of allowing the user to touch the strings directly. Since this input device was more agnostic of key–that is, you could center a song around any of the keys on the keyboard much more easily than you could on a string instrument–it became desirable to divide the octave into some number of equal parts, to facilitate playing in different keys. The result, known as equal temperament tuning, gives us the standard keyboard we know today, with seven white keys and five black keys per octave, each separated by a twelfth of an octave, or a half step.

The weird thing is, equal temperament tuning is a compromise, mathematically. A “perfect fifth” in equal temperament tuning is not exactly equal to the one that results from the third harmonic of a string. But that’s out of scope for this post.

If you play every note on the keyboard in order, you get what’s called a chromatic scale, but it doesn’t sound very musical. Most songs limit themselves to using only seven of those twelve notes, which brings order to the chaos in the way that limiting yourself to a certain color palette or set of shapes helps to define an art style. Which seven notes you choose determines which style it sounds like. Sets of seven notes, the premade color palettes of music, are called diatonic scales, or a series of roughly equally spaced pitches spanning an octave sort of based on the first few harmonics that sound “good” to a human ear. The white keys on a keyboard make up a diatonic scale, and the black keys fill in the gaps.

Interval chart & other terminology

Here’s a list of intervals, or distances between any two notes on the keyboard, in ascending size.

| Distance (half steps) | Interval name | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minor second | C-C# |

| 2 | Major second | C-D |

| 3 | Minor third | C-Eb |

| 4 | Major third | C-E |

| 5 | Perfect fourth | C-F |

| 6 | Tritone | C-F# |

| 7 | Perfect fifth | C-G |

| 8 | Minor sixth | C-Ab |

| 9 | Major sixth | C-A |

| 10 | Minor seventh | C-Bb |

| 11 | Major seventh | C-B |

A chord is three or more notes played at the same time. A triad is a chord that consists of three notes, each separated by a third from the next closest one. There are different types of triads depending on the permutation of thirds used. For example, C-E-G forms a major triad.

The tonic is another name for the first note in a scale. The dominant is another name for the fifth note.

A cadence is two chords played one after the other that ends a phrase. Types of cadences include plagal (the “amen” cadence), authentic (the most commonly used cadence, which goes from the triad based on the fifth note of the scale, known as the dominant chord, to the triad based on the first note of the scale, known as the tonic chord), and deceptive.

A leading tone is a note that’s a half-step away from another note that it resolves to. Usually this refers to the seventh note of a seven-note scale. When the seventh note of the scale is a whole step away from the octave, that scale is said to lack a leading tone.

Diatonic (White Key) Scales

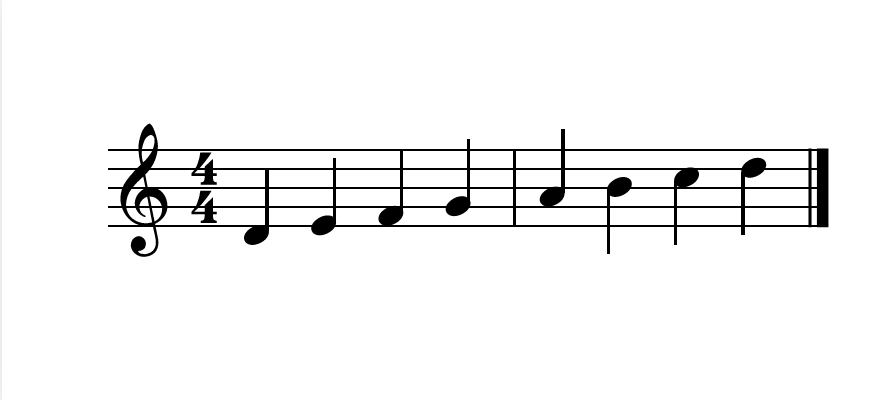

If you play every white key in an octave starting and ending with C, you get a recognizable major scale. But what if you start and end on a different note? Each of those is known as a mode, is named after a historical place in Greece, and has an associated mood or style. Some modes are much more commonly used than others.

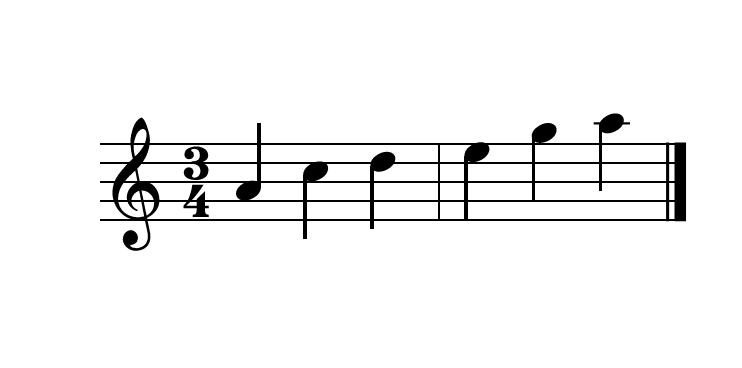

Ionian (Major)

A major scale is also known as Ionian mode. Not much to say about that one. Think of a pop song; it’s probably Ionian. To human ears, this scale tends to sound happy or normal.

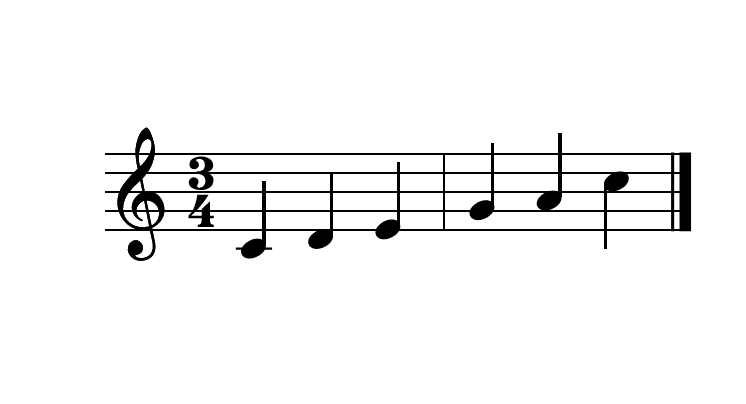

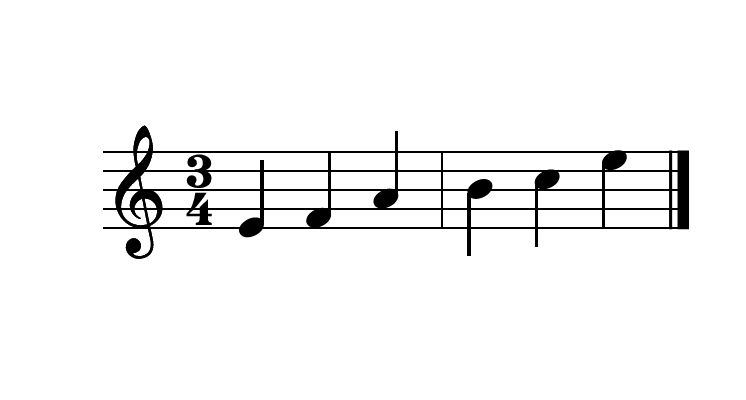

Aeolian (Natural Minor)

If you play all the white keys starting and ending on A, you get Aeolian mode, also known as a natural minor scale. While the interval between the first, second, fourth, and fifth tones are the same as in Ionian mode (C-D and A-B are both major seconds; C-F and A-D are both perfect fourths; C-G and A-E are both perfect fifths), the rest of the intervals are a half-step smaller: instead of a major third, sixth, and seventh, Aeolian has minor ones. To human ears, this sounds sad or subdued.

Why does the standard minor scale include a major second instead of a minor second? Good question. It just sounds better.

Dorian

If you play all the white keys starting and ending on D, you get Dorian mode, or minor with a raised sixth tone. This one isn’t super common–it’s a single half-step away from melodic minor (covered later) but it’s missing the leading tone, which is kind of an important feature.

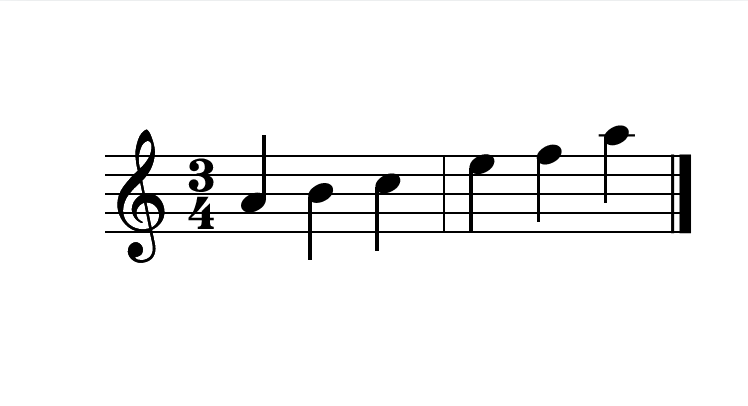

Phrygian

This mode is what I think deserves to be called “natural minor”, since it contains only minor and perfect intervals. The minor second makes it sound Zen, or Egyptian.

Lydian

Lydian is one of the two modes that suffers from a tritone, the “devil’s interval”, in a strategically important place. Lydian lacks a good-sounding four chord. That means no one seriously uses this one.

Mixolydian

Mixolydian, or major with a lowered seventh, is commonly used in pop songs. However, pure Mixolydian is fairly rare, because it lacks the leading tone that’s important for making the five-one authentic cadence sound conclusive. Most pop songs that utilize a lowered seventh raise it again some of the time to use as a leading tone. But some just rely on a four-one plagal cadence instead.

Locrian

Like Lydian, Locrian mode contains a tritone in an important location: between one and five. That means it lacks both a good-sounding dominant chord and even a usable tonic chord, making this mode basically untenable for Western music.

Pentatonic (Black Key) Scales

Another big family of scales are the pentatonic, or five-note scales. These are usually formed by using only a subset of notes from various diatonic scales, and were often found in more ancient or primitive musical traditions. I’m calling these “black key” scales because on a standard keyboard, the black keys form a family of pentatonic scales that don’t contain any half-steps. But not all pentatonic scales listed here can be played solely on black keys. Furthermore, notating using accidentals is a little harder to look at and obscures these scales’ relationship with the white key scales, so I’ll continue notating them using white keys for legibility.

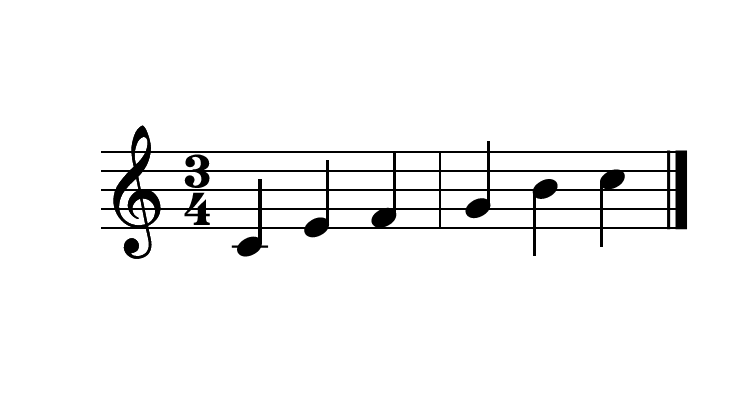

Major Pentatonic

Based on the Ionian (major) scale, this pentatonic scale omits the fourth and seventh notes, those pesky half-steps. Who needs ‘em? As a result, this scale sounds very hymnal, with simple, righteous chords that know their roles.

Minor Pentatonic

Based on the Aeolian (minor) scale, this pentatonic scale also omits the fourth and seventh notes, but in minor keys, this doesn’t eliminate all half-steps.

These are the same notes used in the Japanese national anthem, “Sakura Sakura”, but in Japanese traditional music, they hear the tonic as being on E rather than A (in this key). I don’t hear it this way–to me, it sounds like that song uses the minor pentatonic scale rather than the Miyako-Bushi scale (described below).

It’s much more common to omit the same two notes as in the major pentatonic scale, eliminating all half-steps, which are, from this starting position, the second and sixth notes. This brings us back to a scale playable on black keys only, and forms the basis of the blues scale (more on that later).

Mikayo-Bushi

This scale is based on the Phrygian mode, omitting the third and seventh notes. It’s very common in traditional Japanese music, and is also known as the “sakura scale” because it’s used in the Japanese national anthem, “Sakura Sakura”.

Decide for yourself–does it sound like this song is in the key of A, or E?

Island

This scale is a different subset of the Ionian (major) scale, omitting the second and sixth notes, and therefore preserving all instances of half-steps. It’s also used in Japanese traditional music, but sounds more “islandy”, though I can’t pinpoint exactly why.

Other Common Scales

Blues

This funky scale is based on the minor black key scale, but adds two blue notes (a sort of catchall term for any note that doesn’t have any good reason for being in the scale other than sounding cool), one between the fourth and fifth and adding a raised sixth.

Alternatively, you could swap the raised sixth for one between the seventh and octave, allowing parallel funky walkups.

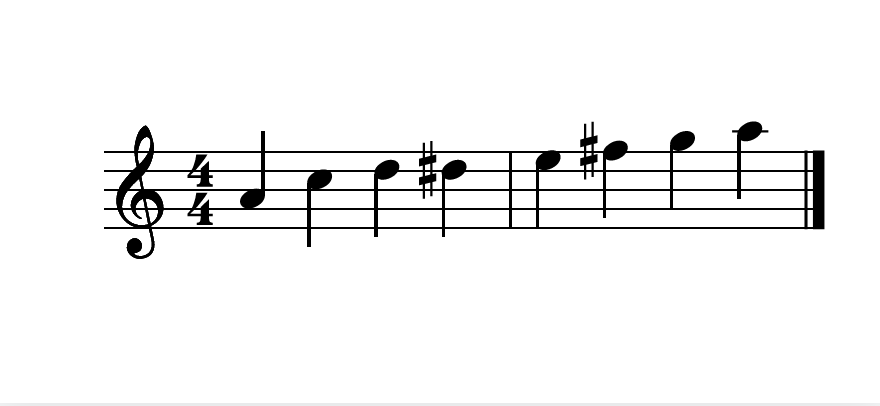

Middle Eastern

So far, none of the scales we’ve covered have contained any intervals larger than a major second between adjacent numbered notes. Some scales omit notes, leaving thirds between the ones that are left, but if you filled the missing numbers back in, you wouldn’t have any large gaps. This scale mixes major and minor elements, with two points in the scale where adjacent notes are separated by a minor third.

Harmonic and Melodic Minor

I’d be remiss if I didn’t cover these two scales, since they’re considered more “basic” (and are more often required curriculum for piano scales), but I don’t think they’re particularly interesting, either sound-wise or theory-wise. Basically, since minor scales suffer from lack of a leading tone, the harmonic minor just adds that back in, raising the seventh to within a half-step of the octave. The melodic minor also raises the sixth, to eliminate the minor third that results in the harmonic minor and sounds more “harsh”.

Thanks for bearing with me through this total non sequitur. I’ll go back to dinosaur content next month, I promise!