I recently had my bachelorette party, and where better to go than Denver, the land of skiing and dinosaurs? (Unconventional, I know.) One of the major draws was the famous Denver Museum of Nature and Science, possibly the best paleontology museums in the country (the other candidate being the Field Museum in Chicago). I was super impressed by the wealth of real fossils on display–not only were their enormous mounted skeletons 50-80% real bone, they even had individual specimens I’d read papers about, like Icaronycteris the transitional bat and an Edmontosaurus skin impression. But of course it wasn’t quite perfect–some of the artistic choices and mounting postures were outdated or questionable. In this post I’ll give my opinion on a few of the Mesozoic exhibits!

Coelophysis

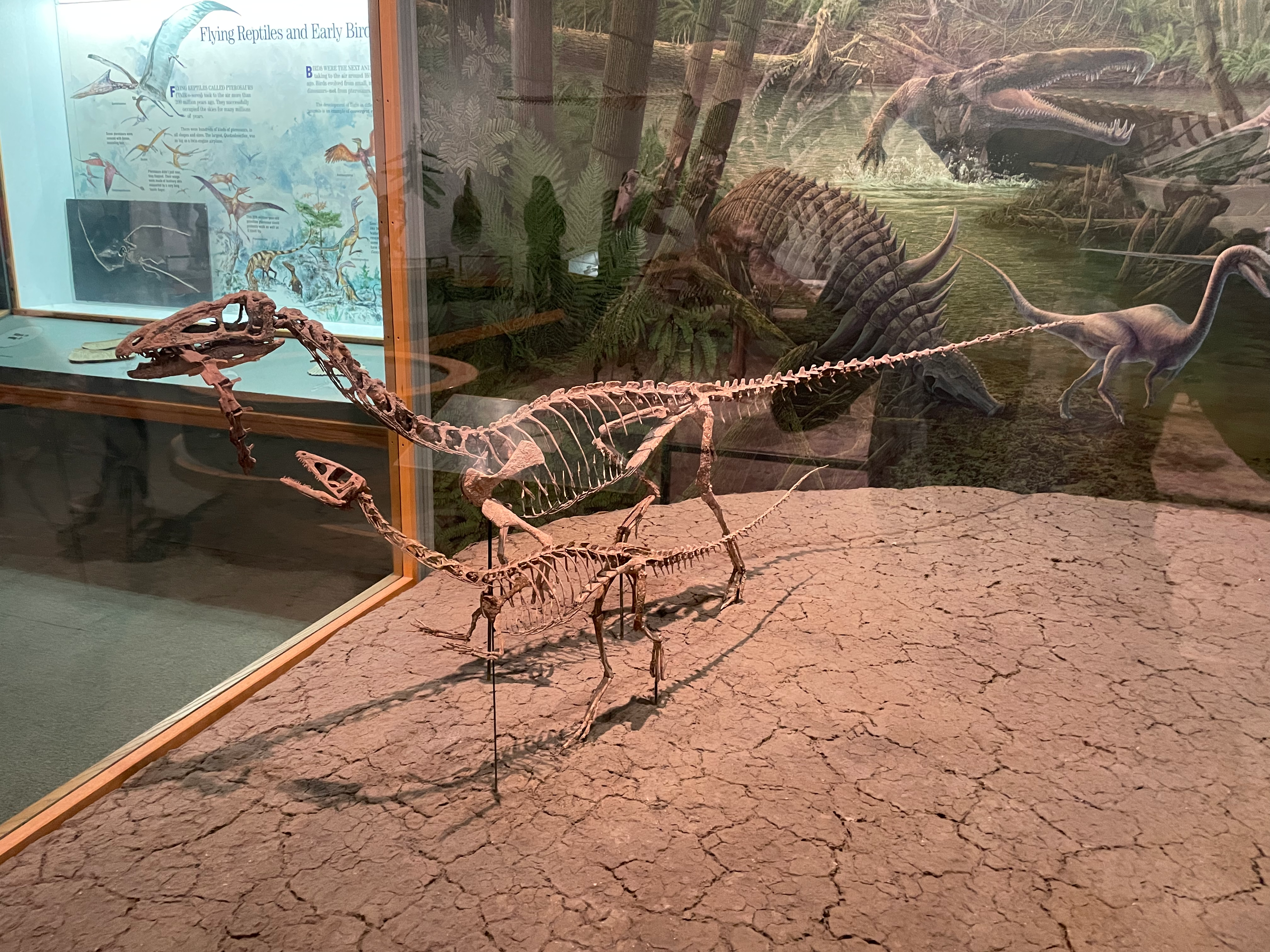

There were two exhibits featuring Coelophysis, the snake-necked Triassic dinosaur. One was a pair of mounted skeletons, an adult and a juvenile, fighting over a bony scrap in front of a Triassic mural, while the other was a single animal in cross-section, showing the bones, muscle, and skin layers.

The skeletons I’d give a 7 out of 10: they are entirely complete, including the belly ribs known as gastralia, and are mounted well, with no posture impossibilities (the hands and arms are oriented correctly, the scauplocoracoid (shoulder girdle) is connected in front, the legs are wide enough to leave room for a body cavity). And the mural is pretty good as well, depicting the phytosaur (croc mimic) Redondasuchus and the aëtosaur (armored croc) Desmatosuchus as well as a living Coelophysis. The two croclike animals are depicted accurately; my only gripes are that Coelophysis has pronated hands (palms facing backward or downward rather than inward), is scaly rather than fluffy, and has a weird hunchback. Minus three points.

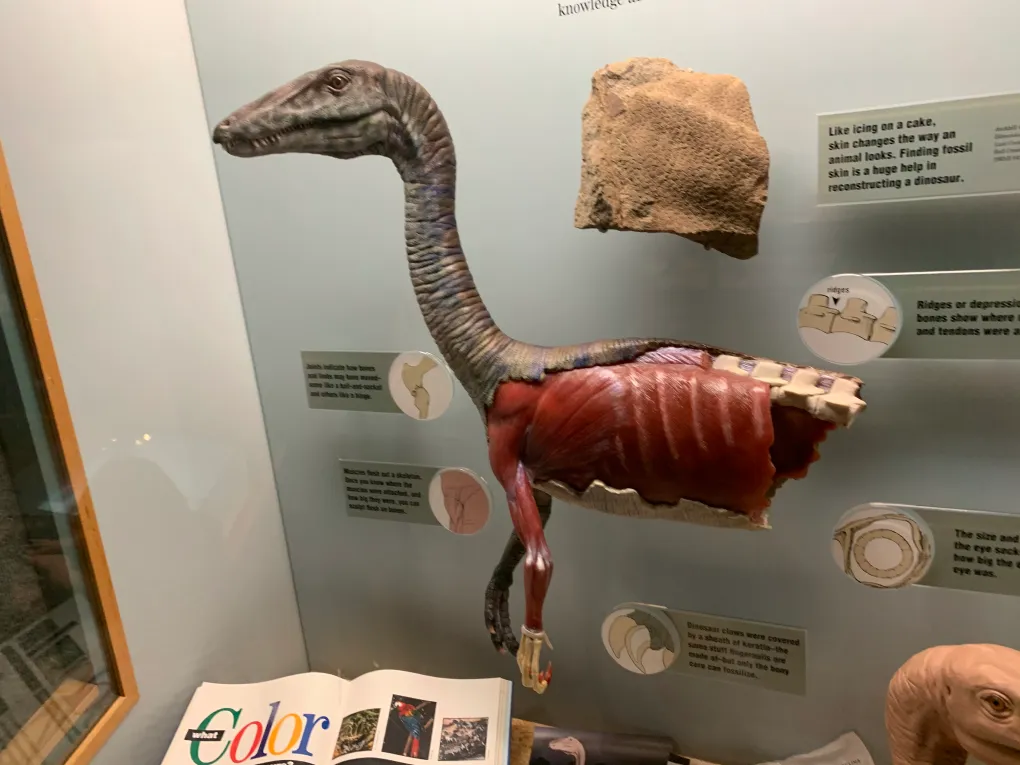

Unfortunately, the Coelophysis skin is worse:

While all the information presented on the signs is accurate (though pretty basic), the centerpiece is quite bad. Only the skin-covered hand is pronated for some reason, its teeth are sticking out of its mouth (not allowed except in aquatic animals–otherwise they’d dry out), its skin is super wrinkly and amphibian-like instead of birdlike and it should have some fluff somewhere, and it’s pretty shrink-wrapped–you shouldn’t be able to see the outline of the back of its skull. Furthermore, the piece of fossilized skin shown next to it belongs to an Edmontosaurus, a completely unrelated dinosaur that lived hundreds of millions of years later than Coelophysis. This skin sample is an incredible specimen, but I would have displayed it next to the mounted Edmontosaurus skeleton and had some more words dedicated to it specifically. Minus seven points for a total of 3 out of 10.

Allosaurus and Stegosaurus

Now this was one of the things I came specifically to see: Colorado’s state fossil, Stegosaurus, fighting its arch-rival, the classic predator Allosaurus.

Stegosaurus is putting its body between its baby and the predator, baring its back plates and swinging its thagomizer, while a herd of Nanosaurus (labeled Othnielia–one of a group of 5 names recently absorbed into Nanosaurus) runs away from the confrontation. All of the skeletons are again highly complete, with Allosaurus’s gastralia and Stegosaurus’s neck scutes in place (both sets of scleral rings are missing though). The scene is believable–usually, the paleoart trope is to show two evenly-matched dinosaurs fighting for no apparent reason, something that is dramatic but very rare in the real world due to the high risk to both parties. In this scene, the Allosaurus was trying to pick off a Stegosaurus baby, much more typical predator behavior, and didn’t realize that the parent was nearby. We don’t have evidence for or against Stegosaurus taking care of its young, but other dinosaurs, including Allosaurus and of course the somewhat more closely related Maiasaura, are known to have done so, so it’s a plausible scene to depict. 9 out of 10.

Thalassomedon

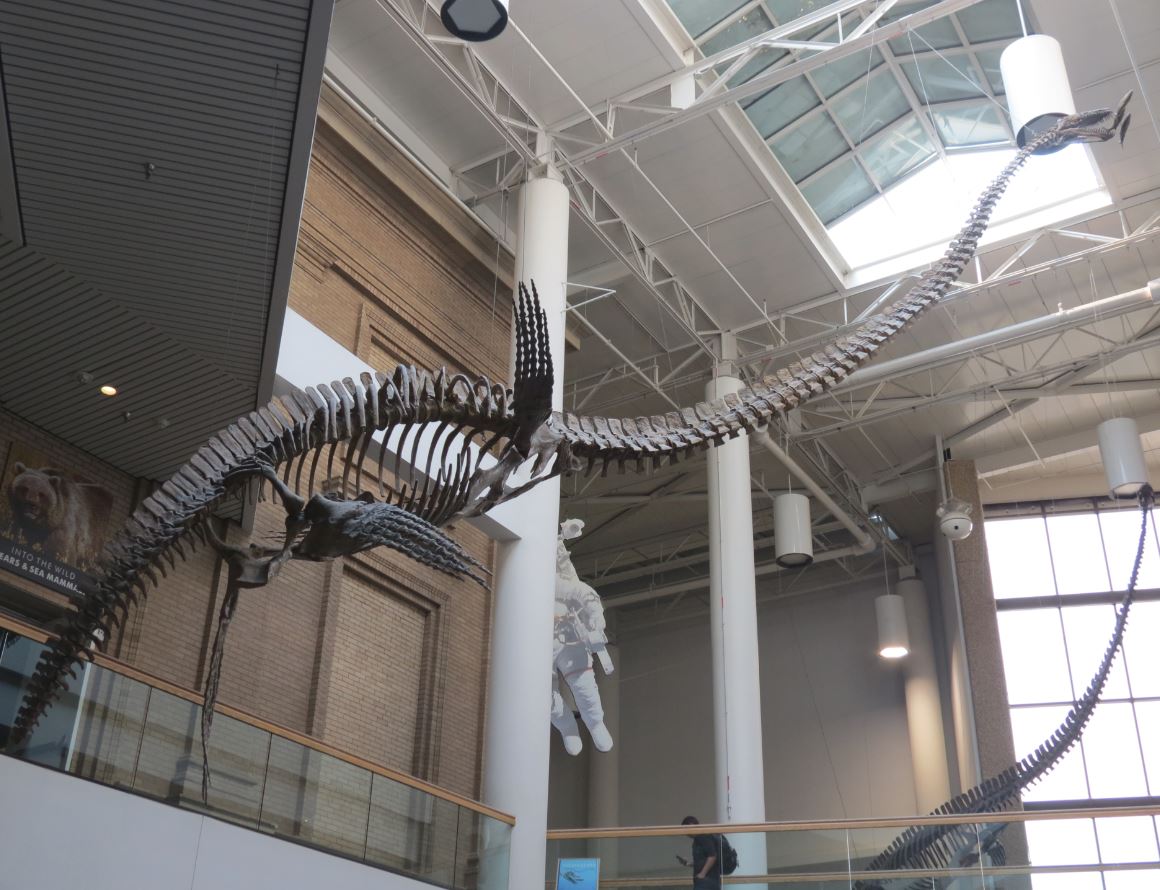

There are two enormous mounted Thalassomedon (a type of elasmosaurid plesiosaur) skeletons in the main hall, impressively spanning between floors so you can see them from many angles.

This mounting decision is particularly effective for this type of animal because of its odd proportions: the neck is so long that it’s difficult to see the tiny head at the same time as the body, and it’s hard to appreciate the overall size of the creature while simultaneously taking in details. The different viewing platforms highlight different aspects of its anatomy.

One of the highly complete skeletons is displayed in a paddling pose with its mouth about to close on a couple of small fish, while the other appears to be coasting. The two notable display choices–prey type and paddling posture–are both based in fact. Elasmosaurs would have eaten small fish, as evidenced by their stomach contents and tooth morphology (not to mention that larger prey would have needed to be torn, something elasmosaurs don’t appear to be very good at, to fit down that skinny neck). And hydrodynamic studies show that plesiosaurs probably paddled with the hind fins lagging the front, following in their wake to reduce drag. This is how the paddling Denver Thalassomedon is posed. 10 out of 10! The only thing I can think of that would improve this display is the inclusion of gastroliths, or stomach stones, which elasmosaurs used to mash up their food.

Xiphactinus and others

Like the huge aerial elasmosaurs, this is another display that wowed me: huge, intact slab fossils of various giant marine animals from the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow ocean that bisected North America during the Cretaceous.

From top to bottom and left to right, we have the mosasaur Platecarpus, the large suction-feeding fish Gillicus, the barracuda-like Cimolichthys, the ichthyosaur Stenopterygius (which I’ve drawn multiple times before), the giant predatory fish Xiphactinus, which has the remains of another Gillicus preserved in its stomach, and the predatory fish Pachyrhizodus, which is more often preserved with soft tissues than other Cretaceous fishes, for some reason. And, of course, the hanging mount of the large leatherback turtle, Protostega. For the most part, these fossils are just presented as-is, with little artistic interpretation required. Still, they are quite stunning, and a less well-endowed museum could dedicate a full display to each. 10 out of 10, very impressive. The only thing I would add would be some artistic renditions of these animals in life, so that the public could better appreciate the visual difference between a mosasaur, ichthyosaur, and fish, which have similarly-shaped skeletons due to convergent evolution.

Edmontosaurus

As if the fighting Stegosaurus and Allosaurus, enormous Diplodocus, and Gargoyleosaurus holotype weren’t enough attractions for the main hall of dinosaurs, there’s also an Edmontosaurus that is 80% real bone and 20% reconstructed. It’s impressively large, and comes complete with its scleral rings and even its ossified tail tendons, bony struts that would have kept the tail stiff in life.

The fact that this specimen is 80% real is mind-blowing. I feel honored that the museum trusts the public not to damage this priceless heirloom. This individual is particularly cool because you can see a wound, about a third of the way down the tail, where a Tyrannosaurus took a bite, but the Edmontosaurus managed to escape and heal. My only gripe is that its hind legs are way too erect of a posture–it’s standing with its knees locked, like they tell you not to do in marching band. The art on the sign below depicts this posture as well, so at least they’re consistent. 9 out of 10.

Tyrannosaurus

Unfortunately, they can’t all be winners, and the most egregiously inaccurate skeleton of all is mounted right in the entrance hall.

Note: I apologize if you are or you know the child in this picture. The photo I took didn’t end up showing off the anatomical inaccuracies as well as this.

Here is my list of gripes:

- The arms are outside their sockets, and are pointed at an impossible angle.

- The hands are pronated (palms facing forward/down rather than inward), a pose impossible in life without having broken or dislocated wrists.

- The scapulocoracoids (chest bones) are separated in front; they should be touching.

- Its arms are way too close to its head. I don’t know how this happened. Maybe the neck is attached to the wrong place or some neck vertebrae are missing? These first four artistic decisions were probably made in order to get the skeleton’s hands close enough to its face for a promotional photo.

- The rib cage is way too narrow and the gastralia are missing. Tyrannosaurus had a really impressively deep and wide body cavity. Why compromise? Wider would be better for display anyway.

- The knees are too close together. There isn’t room for a body between them.

- The standing leg is way too vertical, with all the joints stacked directly on top of each other. This would have been impossible in life. Imagine straightening your dog’s knee fully–it wouldn’t like it.

- The tail could not have bent like that without breaking or dislocating. This and the vertical posture were probably to make the skeleton take up less horizontal floor space.

2 out of 10. Contrast this with the beautifully-mounted Sue, which visited the Denver Museum once:

Stygimoloch

After that abysmal performance, let’s end on a positive note. This isn’t a fossil, but a diorama, which greets you on your way between the Paleozoic and Mesozoic exhibits. It’s maybe an odd choice, since I would have expected to see a Triassic scene immediately after Dimetrodon rather than an end-Cretaceous one, but it’s such a cool scene that I don’t mind.

Stygimoloch was a medium-sized pachycephalosaur (dome-headed dinosaur) that lived alongside the larger, smoother-headed Pachycephalosaurus in latest Cretaceous Hell Creek. Some believe Stygimoloch is the juvenile form of Pachycephalosaurus, since the former has less of a high dome, and since the dome was used for intraspecific sexual competition, it would have developed in puberty. However, the presence of lots of large horn bases in Stygimoloch and their lack in Pachycephalosaurus leads others (including me) to believe that they were different genera (since spiky horns would probably also be a sexual display characteristic).

Anyway, in this diorama a male Stygimoloch head-butts another in the flank. I like a lot of things about this depiction. First, the general anatomy and postures are very good. They’re not at all shrink-wrapped: they have nicely rounded bellies, important for herbivores, believable musculature, and good skin wrinkling and patagia (skin connecting the hind leg and body). Their patterns are also well done, with a flashy red throat patch and yellow face for sexual display, but more cryptic coloration on the rest of the body optimal for a closed habitat, which is where they would have lived and is what is depicted around them. The dappled pattern on their backs and the low-down countershaded pale underside looks very believable for a medium-small animal in a forested area. The idea they would’ve engaged in flank-butting instead of head-butting is a well-supported one; the high-domed pachycephalosaurs like Pachycephalosaurus are thought to have butted heads like rams while the flatter-domed ones like Stygimoloch would’ve been bison-like shovers. And the horns are speculative–since they’re made of keratin, which is softer than bone, fossils tend to preserve only the base where a horn would have attached, indicating the presence of a horn but not its shape–but they’re both believable and fun-looking. I also just love the facial expression of the one being butted. So adorable! 11 out of 10. Best dinosaur diorama I’ve ever seen. Contrast this depiction of Stygimoloch with the disproportionate, shrink-wrapped, kangaroo-postured, draconian-skinned version from Jurassic World. This is how it should have looked in the movie! (And it shouldn’t’ve head-butted through walls for no reason. Animals don’t just do that.)

Conclusion

Overall, I was extremely impressed by this museum. Most natural history museums are lucky to have a couple mounted fossil skeletons–this one had like thirty or forty! And in general the quality of the art and educational material was very high as well. I didn’t rate the mounted Diplodocus skeleton above since I didn’t have too much to say about it scientifically, but it was definitely awe-inspiring (and page-image-inspiring). I think diplodocids are my favorite sauropods, even though they’re less derived than the Cretaceous titanosaurs. Diplodocids are simultaneously earth-shakingly large and equine-ly graceful, and now that I’ve seen a mounted skeleton of one I think I’m ready to get married.