Brains are very complicated. Throughout scientific history, there have been numerous theories about how they work and what the various parts do, and we’re only beginning to scratch the surface of a more functional understanding. Here’s a very well-written but very long comic on how the human brain works and why listening to and interacting with it is so hard.

Mammals and reptiles (which includes birds) diverged about 320 million years ago, in the middle of the Carboniferous Period. Back then, all animals were pretty dumb. The brainiest ones were very lizard-like, and while some engaged in complex behaviors like parental care, they would overall have been fairly slow, cold-blooded, and simple-minded.

Since our common ancestor wasn’t very smart, that means the intelligence of birds and of primates evolved independently, and probably doesn’t work in the same way. Looking at the bird brain, early scientists didn’t see any familiar structures other than the very ancient brain stem and cerebellum, and concluded that birds couldn’t really be smart, since they lacked the structures we knew mammals needed for cognition. Furthermore, as birds have tiny bodies, they necessarily have tiny brains. They asked, how could they think with such a small brain? (Similarly to how a desktop computer can do more computations than a smartphone.) Hence the epithet “bird brain”.

Obviously, they were confusing form and function. It’s like seeing a boat for the first time and concluding, “It can’t possibly transport anything, since it doesn’t have wheels!” As it increasingly becomes clear the more we study birds, they are smart. And they must do it in a totally different way than we do. However, if human neuroscience is medieval, bird neuroscience is in the stone age. We know very, very little about the details of how the brain actually runs. But figuring it out is important, as understanding how a differently-built brain works will allow us to compare similarities and differences, and thereby deduce what features of the brain are requirements for cognition, and which are just artifacts of our evolutionary legacy.

Predicting Intelligence

One very simple problem that scientists have been refining for decades is, is there a single attribute of a brain that correlates strongly with expressed intelligence? If you can measure that one thing, you can predict how intelligent an unstudied species will probably be.

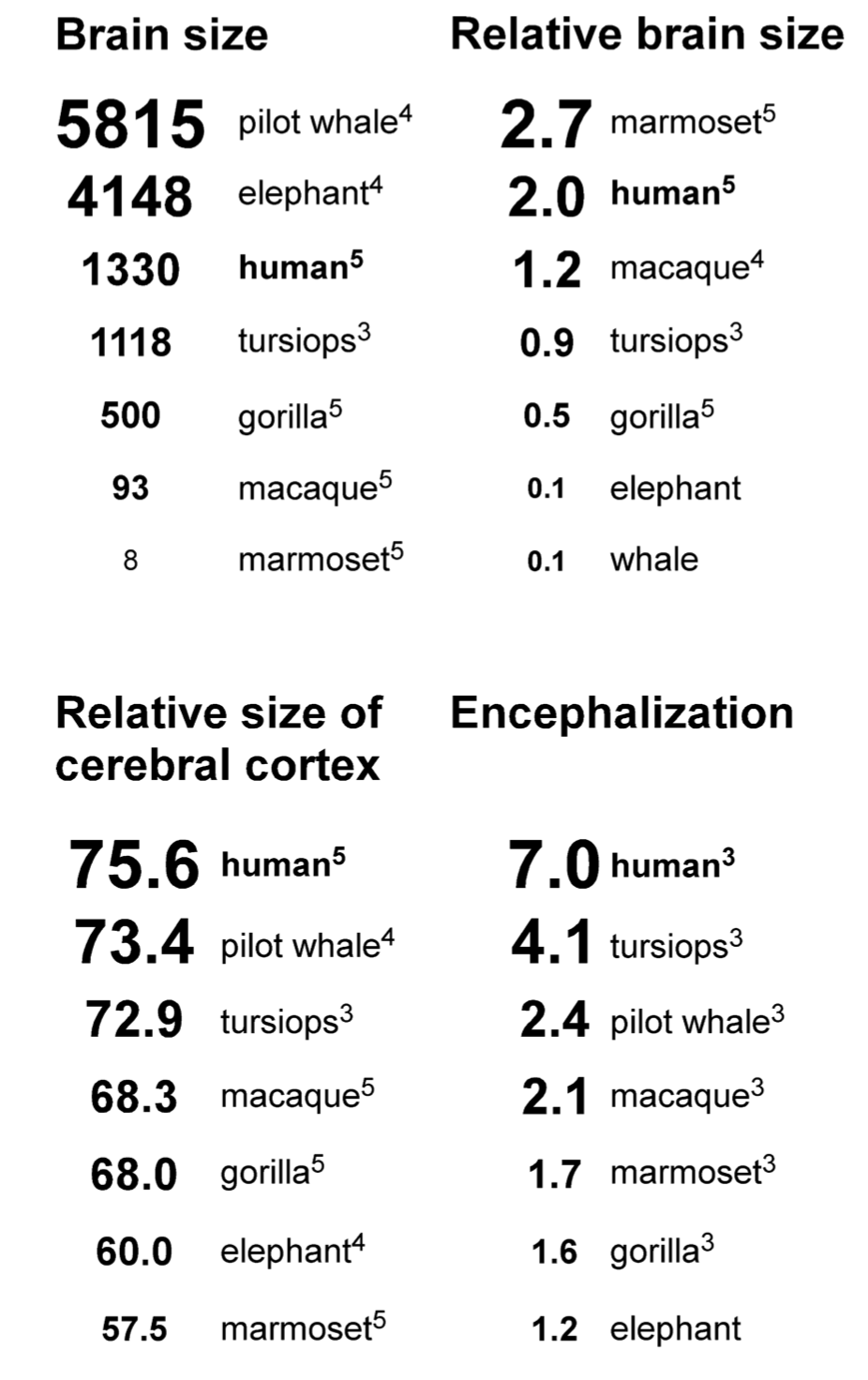

The first proposed metric was pure brain mass. The larger the brain, the smarter the animal. This fits the observed data pretty well…until you notice that it predicts that sperm whales should be six times as smart as humans. So I guess that’s out.

But the brain does a lot more than just thinking–it coordinates and runs the body. So it would make sense that a larger body would require a larger brain just to maintain its basic, non-cognitive functions. So how about dividing brain size by body size to get relative brain size? This fit the observed data a little better. It puts sperm whales much further down the list, but what’s this? The best brain-to-body ratio among mammals is in the marmoset?

Clearly, marmosets don’t build cities or make art, so simple brain to body ratio can’t be right. Maybe the marmoset’s brain is shaped in such a way that more of its brainpower is in the non-thinking zones than humans? A basic understanding of brain anatomy shows that the mammalian cortex is where higher level cognition takes place. So how about the percentage of brain mass that the cortex makes up? This puts humans at the top, finally. But extremely marginally–are we really satisfied with only being around 2% smarter than a pilot whale?

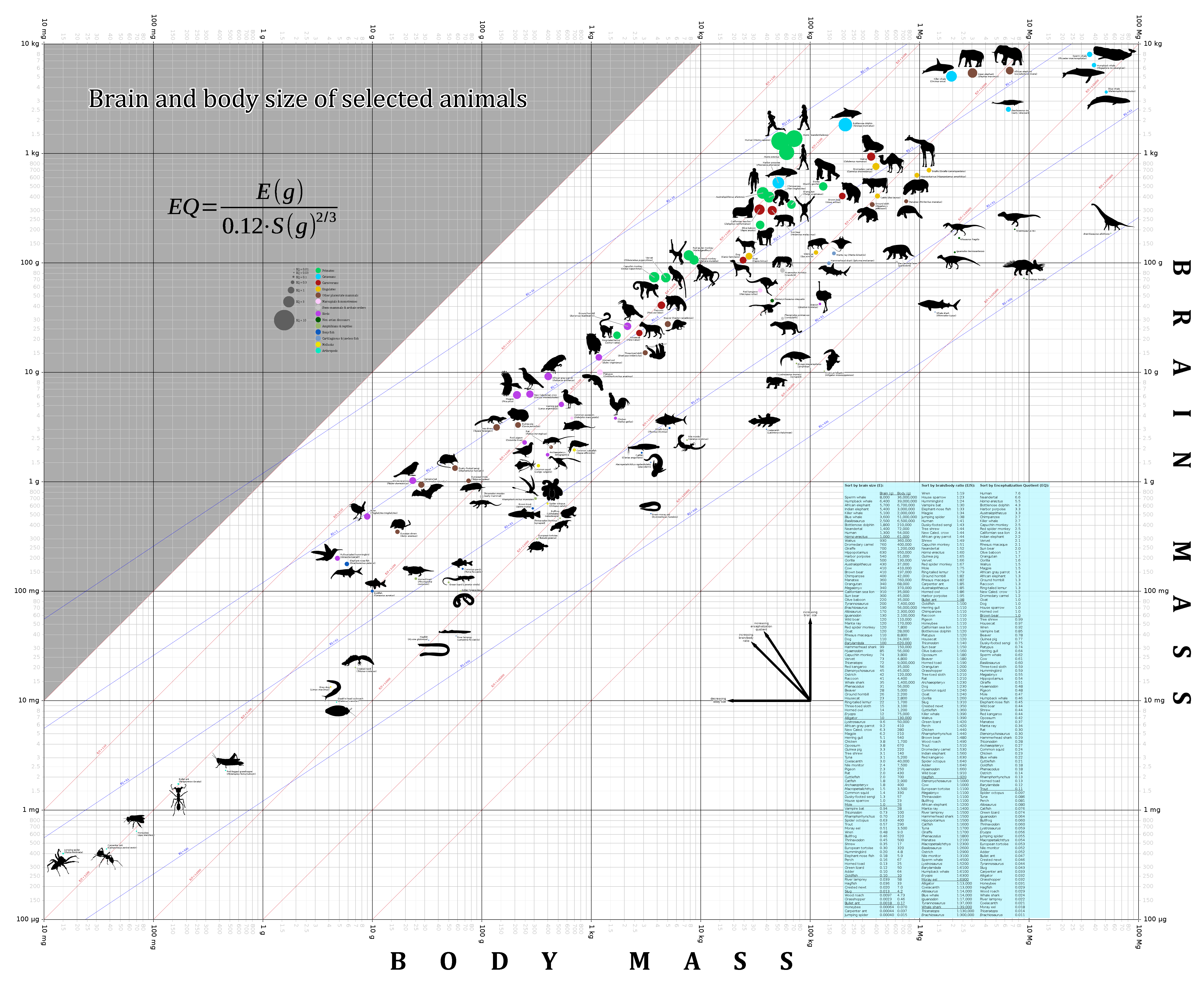

Finally, scientists gave up on thinking of metrics a priori and decided just to best fit a curve to the brain size and body size data at hand. What resulted is the encephalization quotient.

Encephalization quotient, or EQ, simply results from plotting brain size against body size for all mammals on a double-log scale and fitting a line to the observed data. This gives an empirical estimation of how much brain is required to run a body of certain size, and then animals that are above the line are smarter than average, and those below the line are dumber than average. By this metric, humans score quite well compared to any other animal. However, look at the chart for too long, and you start to notice things that don’t seem to make sense. A sperm whale’s EQ is only 0.62, while a guinea pig’s is 0.77, but the former can use language and mourn their dead and are not prone to cannibalizing their own offspring when stressed.

EQ is crude for a few reasons. One is that it assumes that all mammals’ brains scale approximately the same way–that is, across lineages, a given increase in brain mass will result in an animal the same amount smarter. However, as we will see, this is not the case. Second, it doesn’t allow you to fairly compare mammals to other groups. You can make a separate EQ equation for birds, but it will only help you compare birds to other birds. Furthermore, it doesn’t tell us anything absolute about how much brain is actually the minimum required for a certain body size (known as the “grey floor”), but rather just compares everything to the observed average.

Technically, since the equation for EQ is derived only from mammalian data, you are supposed to apply it only to mammals. But it’s telling to see how other animals, such as the magpie and the African grey parrot shown here, perform. If they were mammals, their EQs would be underwhelming–1.5 and 1.4 respectively, just under the walrus and far worse than the sun bear. However, in behavioral tests, corvids (members of the crow family, including magpies–no relation to COVID) and parrots perform at a level more on par with chimpanzees, whose EQ is nearly double that of the birds’. This hints that bird brains must work very differently–and possibly much more efficiently.

Counting Neurons

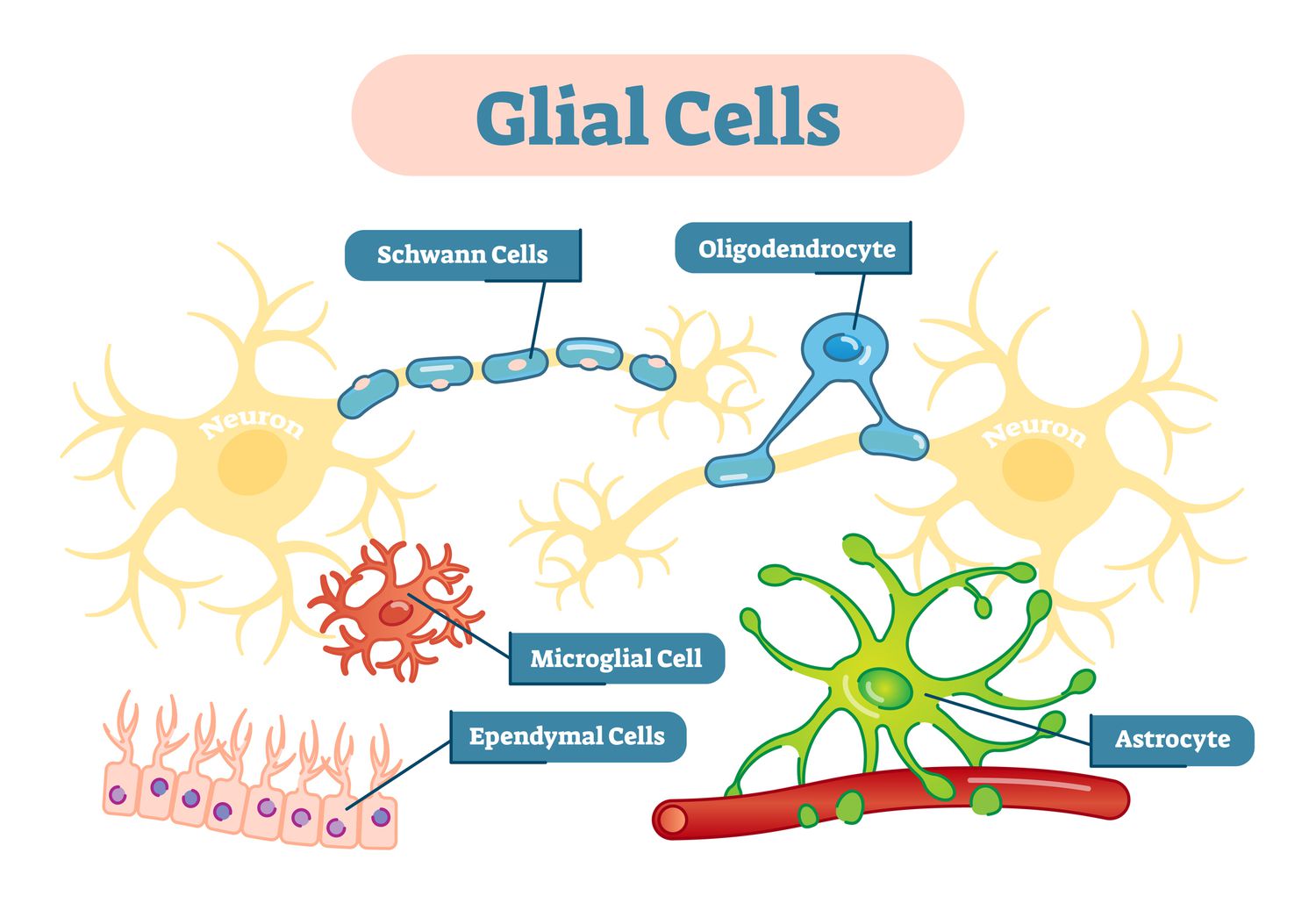

Encephalization quotient remained the best tool for predicting intelligence for two decades, from when it was first proposed in 1985 until technology had improved enough to examine brains in more detail. In 2005, a machine known as the isotropic fractionator was invented, which allowed scientists to count individual neurons in a brain with high accuracy. This provided a much more granular and clade-independent look at brain structure. One fact that had plagued measurements of encephalization was that many brain cells aren’t neurons, but are glial cells, which provide nutrients, scaffolding, waste removal, and repair services to neurons. Simply weighing a brain would not reveal the proportion of neurons, and taking a small sample of a brain to look at under a microscope in order to count the glial cells versus neurons, might not be representative of other parts of the brain. The isotropic fractionator enables scientists to separate out the glial cells and get an accurate neuron count.

Counting neurons resulted in some surprising insights. For one thing, not all mammals’ brains scale the same way, debunking one of the assumptions implicit in the EQ derivation. Rodent brains add neurons a lot more slowly than they add mass, compared to primate brains: “a 10-fold increase in the number of neurons in a rodent brain results in a 35-fold larger brain, while in a primate…the same increase results in a brain that is only 11-fold larger.” [5] Large primates have much denser packing of neurons than large rodents in the same unit mass. Second, the density of neurons can vary widely across different brain regions, and sometimes the way neuron density changes as brains get larger can vary across brain regions as well. Third, larger brains have diminishing returns: neuron density drops as mass increases, as proportionally more support cells are needed. Think of how large desktop computers have lots of fans and fins for cooling, while smartphones use proportionally less space for support; but people still build big computers despite the inefficiency because there are certain tasks smaller ones just can’t do. (It’s not a perfect metaphor. Don’t write me.)

Another interesting finding is that in mammals, the cerebellum scales at the same rate as the cortex, with a majority of neurons being found in the cerebellum. (Did you know that? I didn’t.) The cerebellum is about motor control, balance, and “muscle memory”, not cognition.

And the last thing that’s important to mention is that the human brain is just a scaled-up primate brain. The neuron densities and proportions of our brains are consistent with other primate brains; the thing that makes us special seems to be that our brain is just much larger. This is consistent with the observation that great apes tend to be smarter than monkeys, which have smaller body sizes and smaller brains but similar or better encephalization quotients.

Unfortunately, the isotropic fractionator isn’t able to handle the enormous brains of whales or elephants, so we still don’t have accurate neuron counts for those animals (though we do have estimates from using the microscope technique I mentioned above). The other reason encephalization quotient is still useful, besides ease of use, is that it’s applicable to fossils, as we will see later.

Bird Brains

Okay, enough background about brains. Let’s talk about birds!

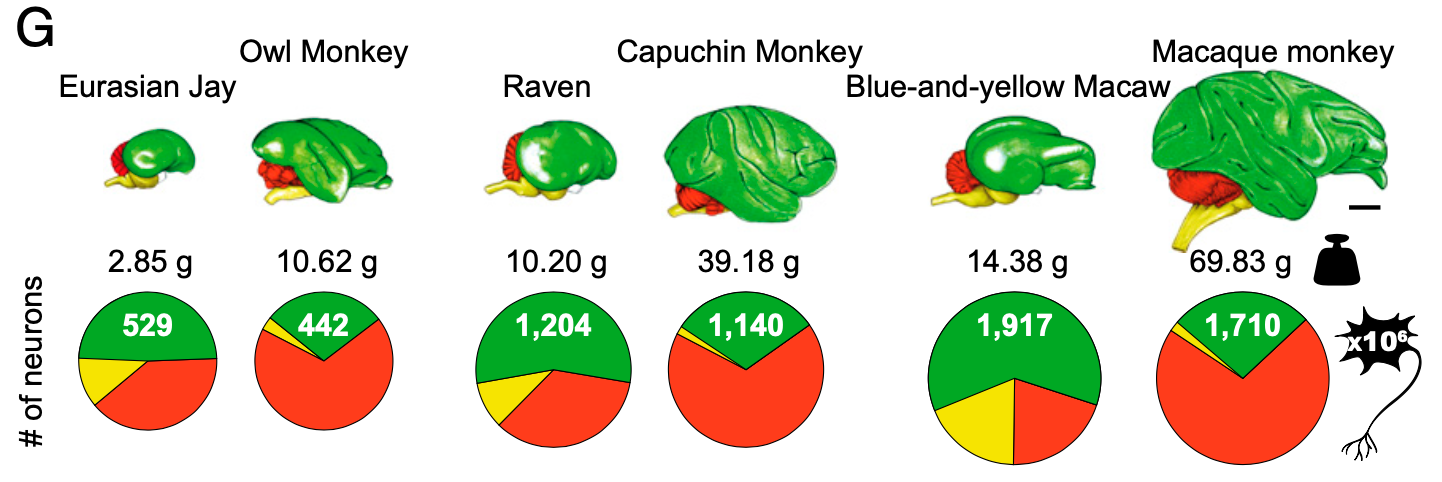

Bird brains were examined using the isotropic fractionator in 2016, and the results were impressive! Not only did they pack way more (two to four times more) neurons into the same mass as primates, they concentrated more of those neurons into the telencephalon (the bird version of the cortex), and they maintained neuron density in the telencephalon at scale. That means that in large brains, a lot less real estate is taken up by the motor-controlling cerebellum, and more is used for cognition.

There are also considerable differences in neuron density across bird families–unsurprising given the differences between primates and rodents I mentioned before. More basal birds like emus and chickens have much less neuron density than more derived birds like songbirds, parrots, and birds of prey. However, even an emu or chicken’s neuron density is similar to a primate’s, so it seems that dense brains are an ancestral feature of all birds, and possibly non-bird dinosaurs.

Another interesting finding from this study is that similarly to how a human brain is just a scaled up monkey brain, the raven brain is just a scaled up songbird brain. Corvids are the largest songbirds, and are also the smartest; and due to the diminishing returns of brain architecture, they have the lowest neuron density of songbirds. However, for birds the returns diminish a lot less quickly than in mammals. [4]

This study also uncovered a structural difference between parrot and corvid brains: the former has many more neurons in the subpallium, an area thought to be related to motor dexterity. That would explain parrots’ aptitude for vocal learning and foot and beak manipulation compared to corvids.

A nice perk of packing your neurons densely is that signal latency is extremely low, due to the short distances between neurons. This is how birds can move and react so quickly–they think in fast motion! For example, the startle reaction time of a human to a visual stimulus is about 250 milliseconds, or 170 milliseconds for an auditory stimulus.* In contrast, a starling reacts to a visual stimulus in only 76 milliseconds, and to an auditory one in 80 milliseconds. That’s two to three times as fast! Birds are watching the world go by at 0.5 speed. Here’s a video of a Cape May warbler catching bugs, filmed at one-fifth speed. If you played this at 5x speed, the head and wing movements would be incomprehensible.

*I’m not familiar enough with brain anatomy to know whether the difference in our reaction time to visual versus auditory stimuli is due to a longer wiring path for visual signals, but that would be my hypothesis.

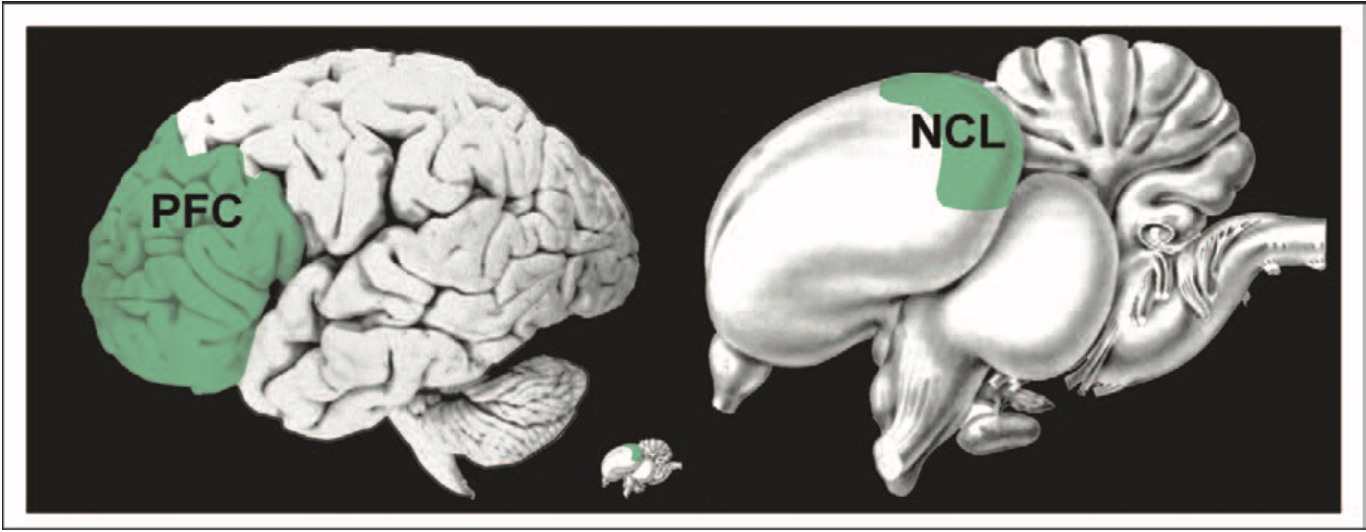

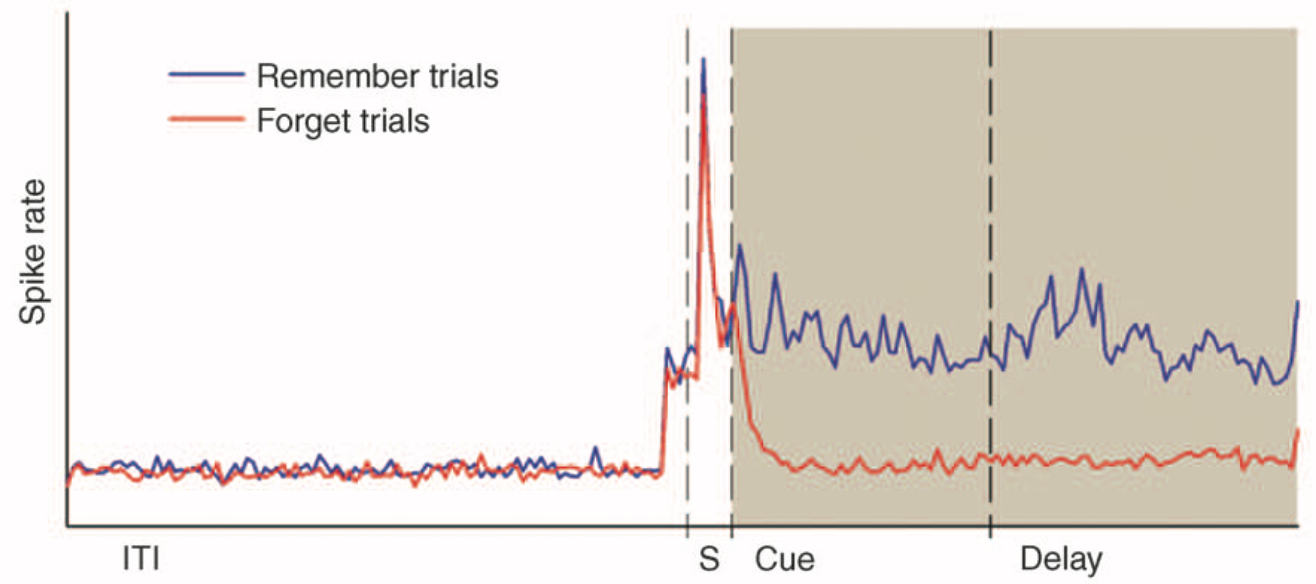

In mammals, the prefrontal cortex is where “executive function” takes place–that is, “planning, cognitive flexibility, decision-making, and inhibiting inappropriate actions” [3]. These are important abilities for intelligent behavior, but birds don’t have anything that looks like a prefrontal cortex, since the common ancestor of mammals and reptiles didn’t have much executive function capability. However, birds are definitely capable of behavior resembling mammalian “executive function”, and close examination of bird brains while they perform decision-making tasks revealed that they use a different brain region, the nidopallium caudolaterale (NCL) for the same types of tasks.

The task the pigeons were doing here is worth mentioning, partly because it’s impressive, and partly because it’s hilarious. The pigeons would see a particular colored light light up, which would then go dark. Then, they would hear a cue sound, which came in two flavors, which corresponded to “remember” and “forget”. Then, if the cue sound had been the “remember” sound, they would be prompted to push a button corresponding to the color of light they had just seen, and receive a reward; if the cue sound had been “forget”, they were not tested or rewarded. Their NCL activity was monitored using implanted electrodes during the whole activity.

The results are logical, but impressive. During the “remember” trials, the pigeons’ NCLs remained lit up the entire waiting period, as if they were saying “yellow, yellow, yellow” to themselves inside their heads. During the “forget” trials, the NCL activity returned to baseline. In a subset of the “forget” trials, the pigeons got a pop quiz–that is, they were tested on the color of light anyway, even though they were promised they wouldn’t be. In those tests, they performed no better than random guessing–they had successfully forgotten!*

* I never thought that “when [pigeons] were instructed to forget” would be a phrase I’d come across in a scientific paper.

In addition to the NCL lighting up in similar situations as the mammalian prefrontal cortex, it shares a lot of structural similarities. The places in the brain that it receives input from, and those that it sends output to, are broadly the same in birds and mammals. There are some key differences, but the degree of convergence in structure suggests that this is the best way to command a vertebrate brain.

The Evolution of the Bird Brain

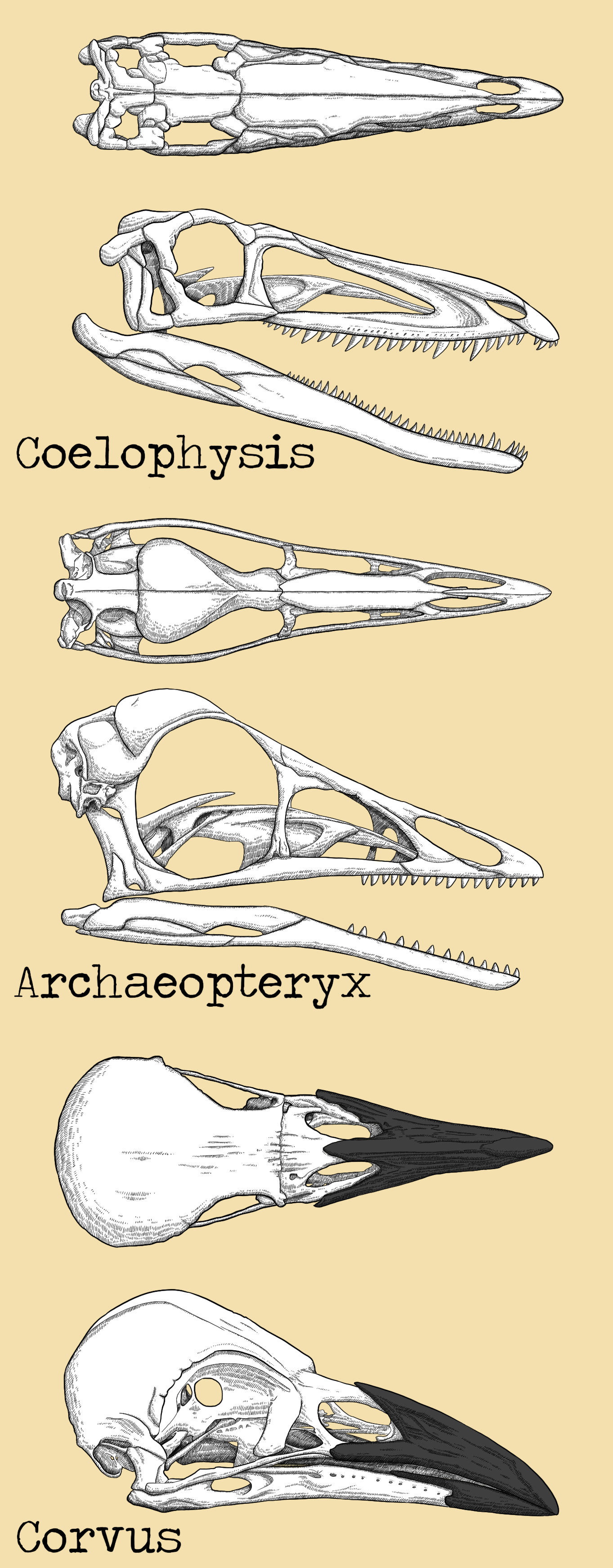

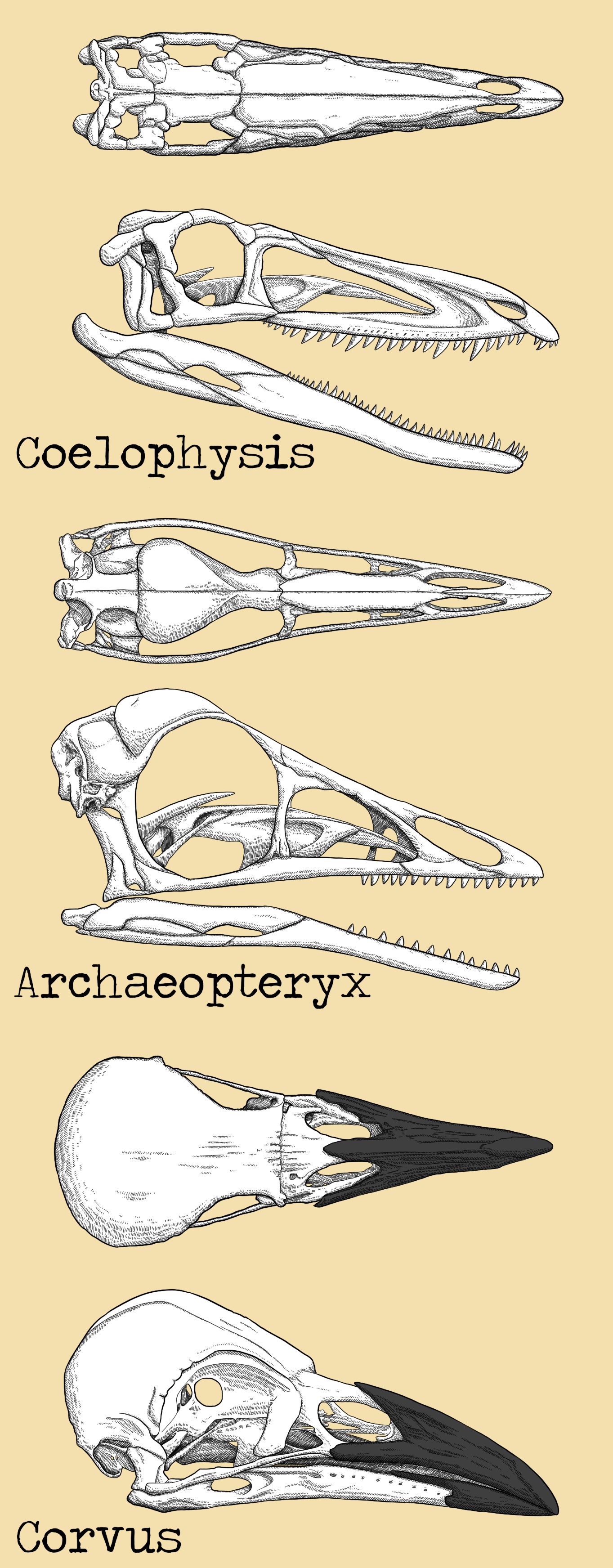

Finally, it’s time to discuss the page image! Here it is again, for your convenience:

Back in the Triassic, when dinosaurs and true mammals were just getting started, both groups’ encephalization quotients were extremely low. I couldn’t find any brain size information on Coelophysis itself, probably because none of the fossils we have are intact enough to make a virtual endocast. (If I’d known that before I started the drawing, I would’ve chosen a different animal’s skull to depict.) But the fox-sized Triassic saurischian Buriolestes (233 million years old), known from an exquisitely 3D-preserved skeleton, would be similarly representative of bird ancestors of the time, and it had an EQ of 0.036, close to that of a modern alligator. (Its brain was similarly structured to an alligator’s as well, indicating that alligator-like brains are the archosaurian ancestral condition.) The Triassic mammal relative Thrinaxodon (247 million years ago), which was also approximately fox-sized, had an EQ of 0.06, but as we’ve discussed above, even back then mammal relatives probably needed twice as much brain to accomplish the same intelligence. Interestingly, no modern mammal even comes close to this low of an EQ. The lowest I could find is the common opossum, with an EQ of 0.284.* These two animals were probably close to the brainiest things around at the time.

* At first, I was surprised that marsupials and placental mammals had members with the lowest EQ (the lowest EQ placental mammal I could find was the naked mole-rat, at 0.329), while platypuses and echidnas, though evolutionarily more basal, were much smarter, with EQs of 0.74 and 0.97, respectively. But on second thought, maybe this makes sense: since marsupials and placentals are much more diverse, they contain both very smart and very dumb members, while monotremes, which only consist of five species, only have average-ish members.

Next, we have the Jurassic bird Archaeopteryx (149 million years old), with an EQ of 0.27. That’s similar to a chicken (0.23)! Chickens are often maligned for being dumb, but they are perfectly functional in the modern world, unlike a hypothetical mammal with 0.06 EQ. A mammal from around the same time, Triconodon (140 million years old), had a similar EQ of 0.28, which is close to that of an opossum, another perfectly functional modern mammal. However, these two animals were again, probably the brainiest things around at the time, whereas chickens and opossums are nowhere near the brainiest today. The ceiling for intelligence has continued to increase, while all the levels below remain populated.

Finally, there’s the bulbous skull of the common raven, with an EQ of 1.66. That’s similar to a gorilla or orangutan. But since bird brains pack in twice as many neurons, we might expect a raven to be as clever as an Australopithecus or a harbor porpoise (EQ = 3.3).

One last note on measuring intelligence. It’s possible that an even better predictor of cognitive ability than neuron count would be synapse count, or the number of total connections between neurons in the brain. This might be more important to intelligence because (a) the number of synapses depends on the number of neurons, so this value encompasses the information we get from neuron count, and (b) developing new synapses is known to be very important to learning and maturation. However, pruning synapses seems to also be quite important, in order to reinforce existing connections and streamline signal paths [9]. Furthermore, we don’t have the technology to count those accurately right now.

References

[1] Urban, T. (2017, April 20). Neuralink and the Brain’s Magical Future — Wait But Why. Wait but Why. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://waitbutwhy.com/2017/04/neuralink.html

[2] Olkowicz, S., Kocourek, M., Lučan, R. K., Porteš, M., Fitch, W. T., Herculano-Houzel, S., & Němec, P. (2016, June 13). Birds have primate-like numbers of neurons in the forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(26), 7255–7260. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517131113

[3] Güntürkün, O. (2005). The avian ‘prefrontal cortex’ and cognition. Current opinion in neurobiology, 15(6), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.003

[4] Veit, L., & Nieder, A. (2013). Abstract rule neurons in the endbrain support intelligent behaviour in corvid songbirds. Nature communications, 4, 2878. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3878

[5] Herculano-Houzel, S. (2011). Brains matter, bodies maybe not: the case for examining neuron numbers irrespective of body size. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1225, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05976.x

[6] Heinrich, B. (2007, May 29). Mind of the Raven. In Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds. Ecco. https://doi.org/10.1604/9780061136054

[7] Herculano-Houzel, S., & Lent, R. (2005). Isotropic fractionator: a simple, rapid method for the quantification of total cell and neuron numbers in the brain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 25(10), 2518–2521. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4526-04.2005

[8] Müller, R.T, Ferreira, J.D., Pretto, F.A., Bronzati, M., & Kerber, L.. The endocranial anatomy of Buriolestes schultzi (Dinosauria: Saurischia) and the early evolution of brain tissues in sauropodomorph dinosaurs. J. Anat. 2021; 238: 809– 827. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13350

[9] Sapolsky, R. M. (2017, May 2). Behave. In The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Press.

[10] Ksepka, D. T., et al (2020, June). Tempo and Pattern of Avian Brain Size Evolution. Current Biology, 30(11), 2026-2036.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.060