The idea behind this post came from a game of Trivial Pursuit, in which I was asked (paraphrased), “Which central Asian lake has shrunk by 90% over the past sixty years?” I didn’t know any Asian lakes other than the Caspian Sea, which is still full, so I did not earn the geography wedge at that time. But when I later looked up the Aral Sea, I wondered how I had never heard of this dramatic ecological disaster. It seemed like something that should be talked about in the same breath as the BP oil spill or Chernobyl.

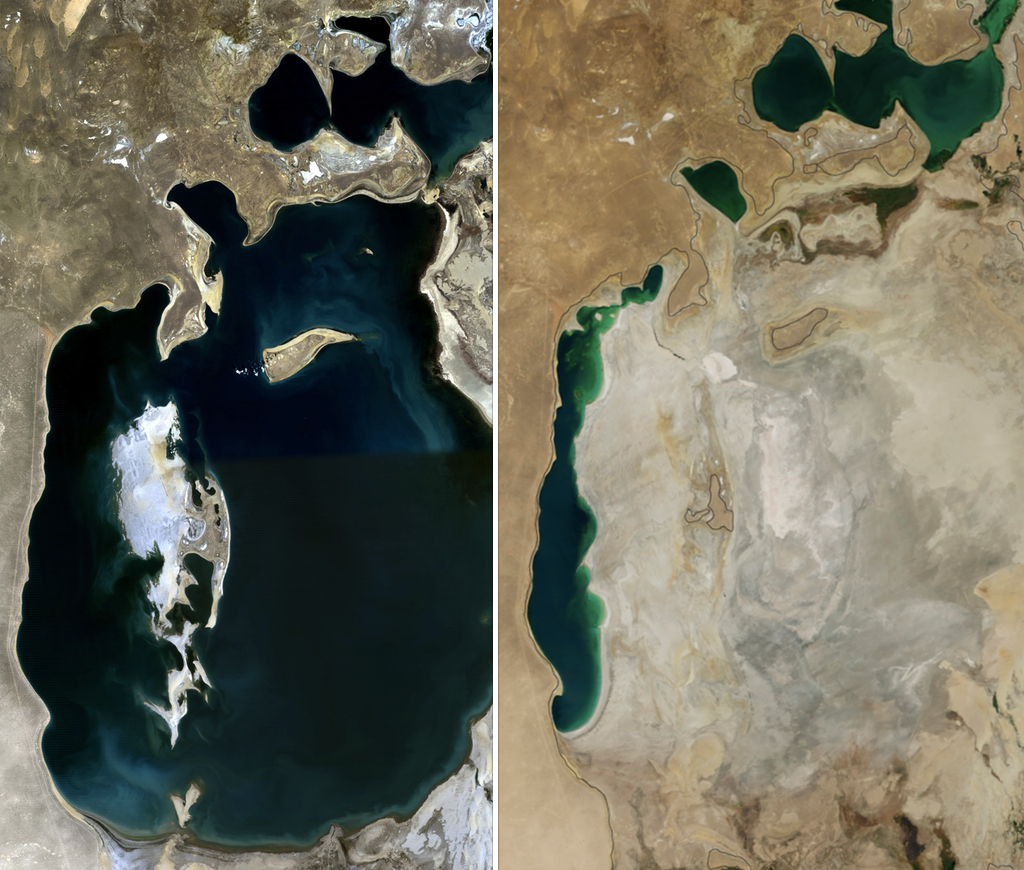

To sum up, here’s a photo showing the change in water level over a period of just 25 years:

And for a sense of scale, this used to be the fourth largest lake in the world–larger than Lake Huron, the second-largest Great Lake. Now, that little northernmost part is only the 41st-largest lake, and the skinny western bit is hypersaline, somewhere between three and six times saltier than seawater, close to the salinity of the Dead Sea.

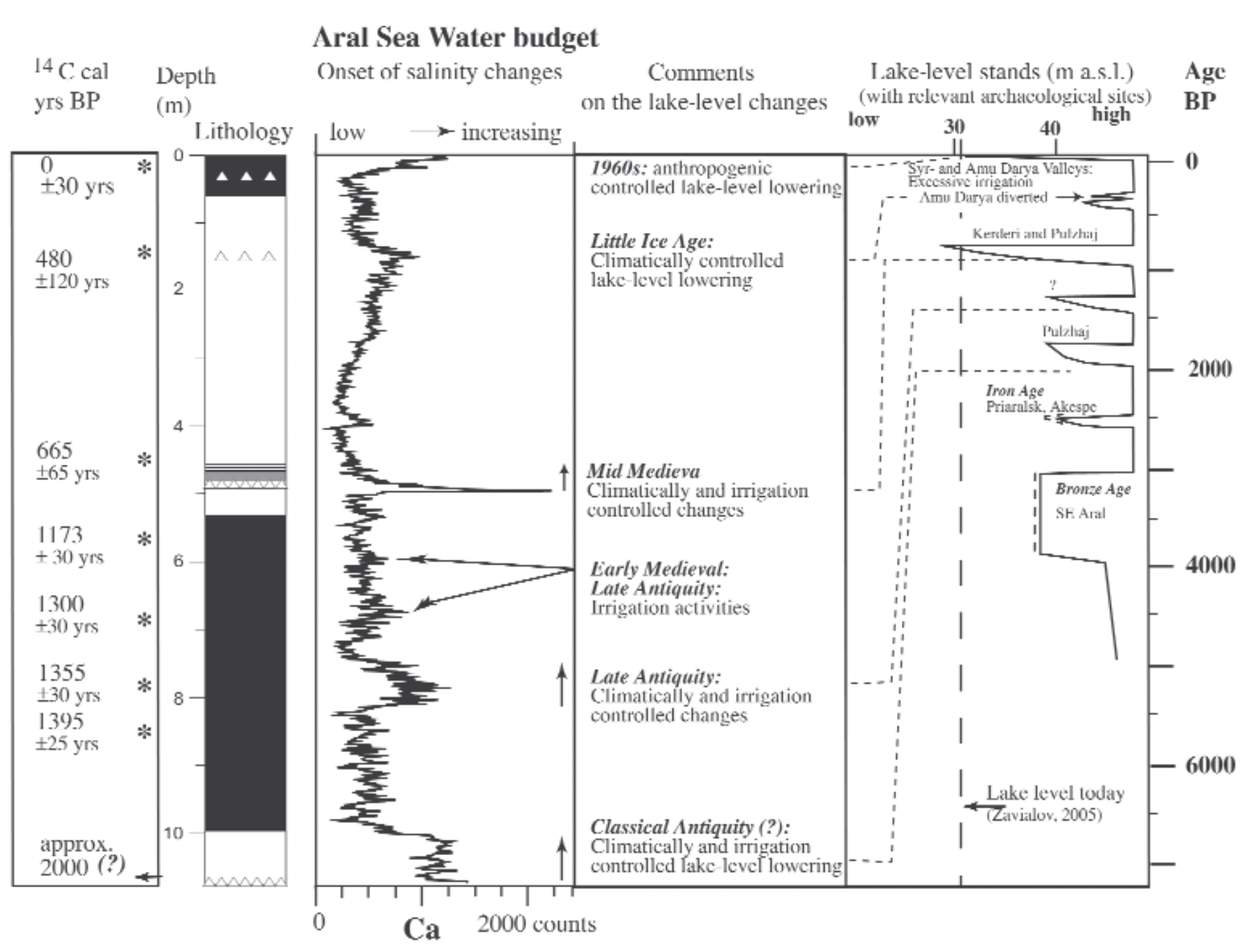

The Aral Sea has had a surprisingly eventful history even before the most recent desiccation. This enormous lakebed has drained and refilled six times within the last five thousand years, and at one of those times, it drained even further than its current state. As more of the lakebed opens up today, archaeologists are finding drowned settlements and groves of tree stumps from the Middle Ages.

Why is this huge body of water so much more volatile than others? What triggers the repeated filling and drying? Is the current drained state actually an ecological disaster, or part of a natural cycle? The rest of this post will attempt to answer these questions.

Modern Desiccation (1960-2014)

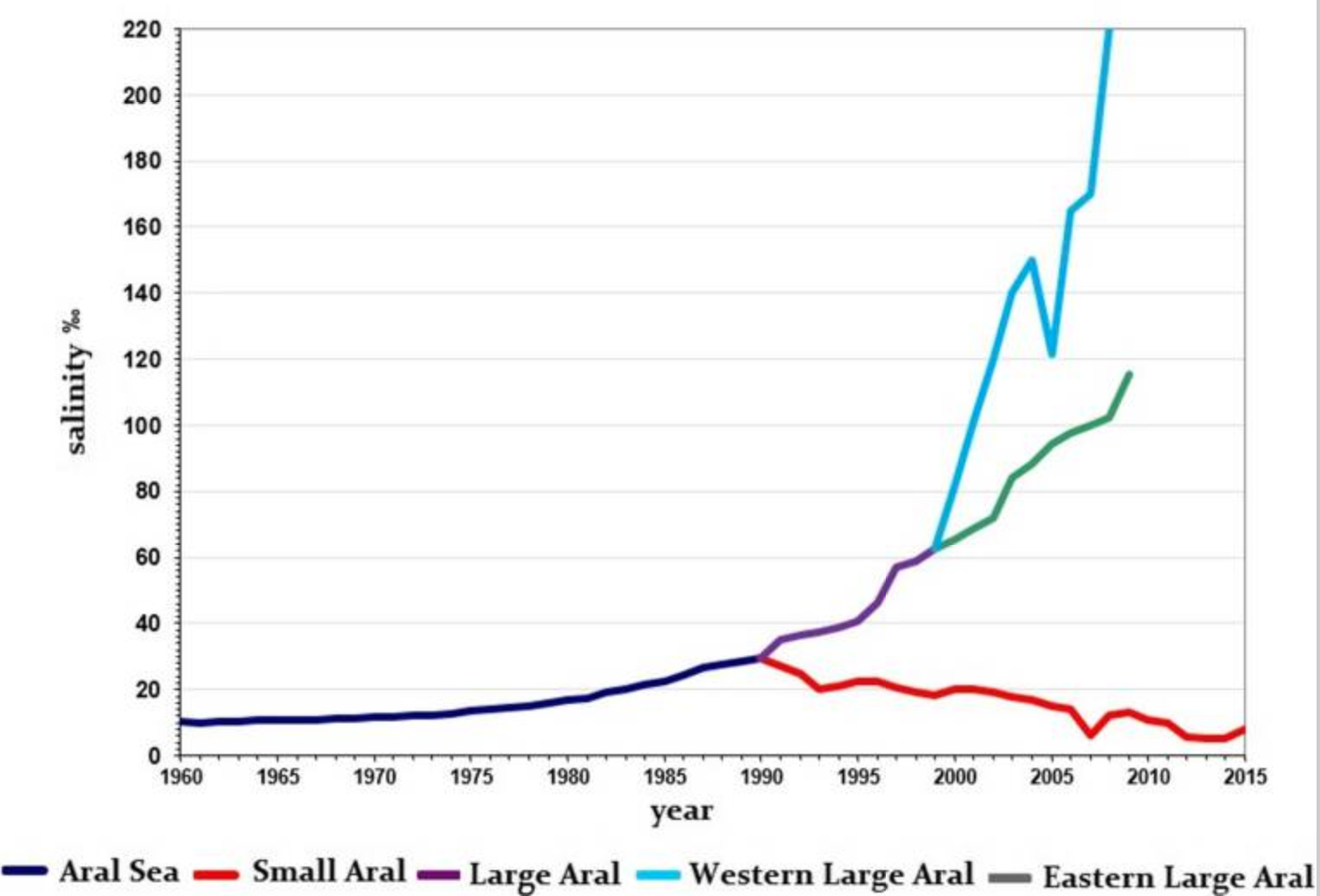

The Aral Sea is what’s known as an endorheic basin (“endo” = in, “rhei” = flow), which is a lake with in-flowing rivers but no out-flowing ones, that maintains its water level through evaporation. Most endorheic lakes are salty, because minerals that are brought in with the river water never leave, but remain dissolved in the water or get deposited on the lakebed. However, most regions of the Aral sea had low salinity (less than 10 parts per thousand (ppt, or ‰)) until recently, and the lake hosted a mostly-freshwater fauna, with some euryhaline (“eury” = broad, “hal” = salt) organisms that can tolerate a wide range of salinities. The climate in the area is semiarid, with expansive deserts cut across by belts of greenery following the rivers and deltas.

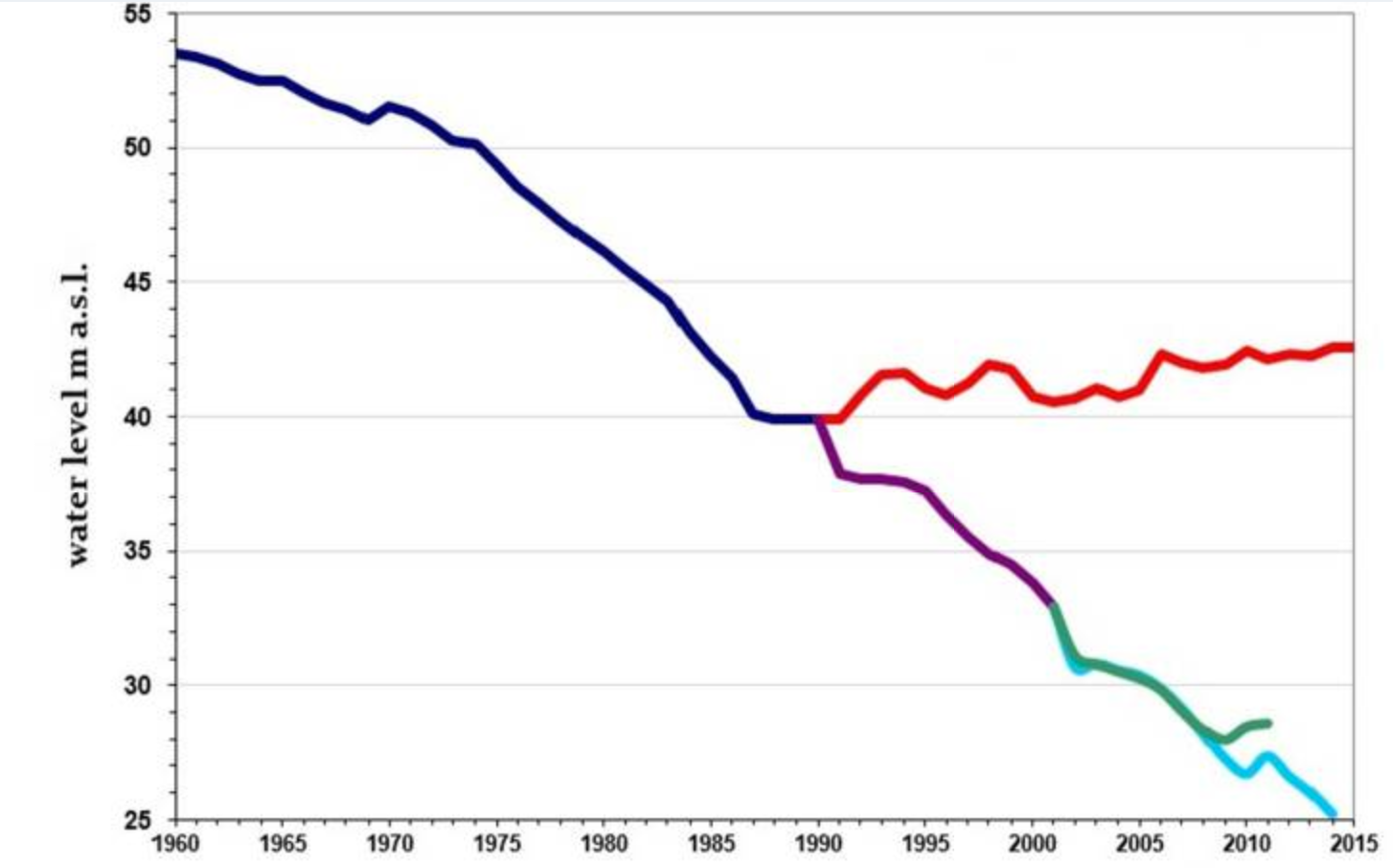

Until 1960, the Aral Sea was fed by two rivers: the Amu Darya in the south, and the Syr Darya in the northeast, which provided fresh water from snowmelt from the Himalayas. The most recent desiccation began in 1960, when the Soviet Union started diverting water from both rivers for the purpose of irrigating cotton fields in Uzbekistan. The canals were made of unlined sand, so as much as 90% of the water flowing through them escaped before it reached its destination. However, Uzbekistan became an important global exporter of cotton, and, through the construction of hydroelectric dams on those and other rivers, an important regional distributor of electricity.

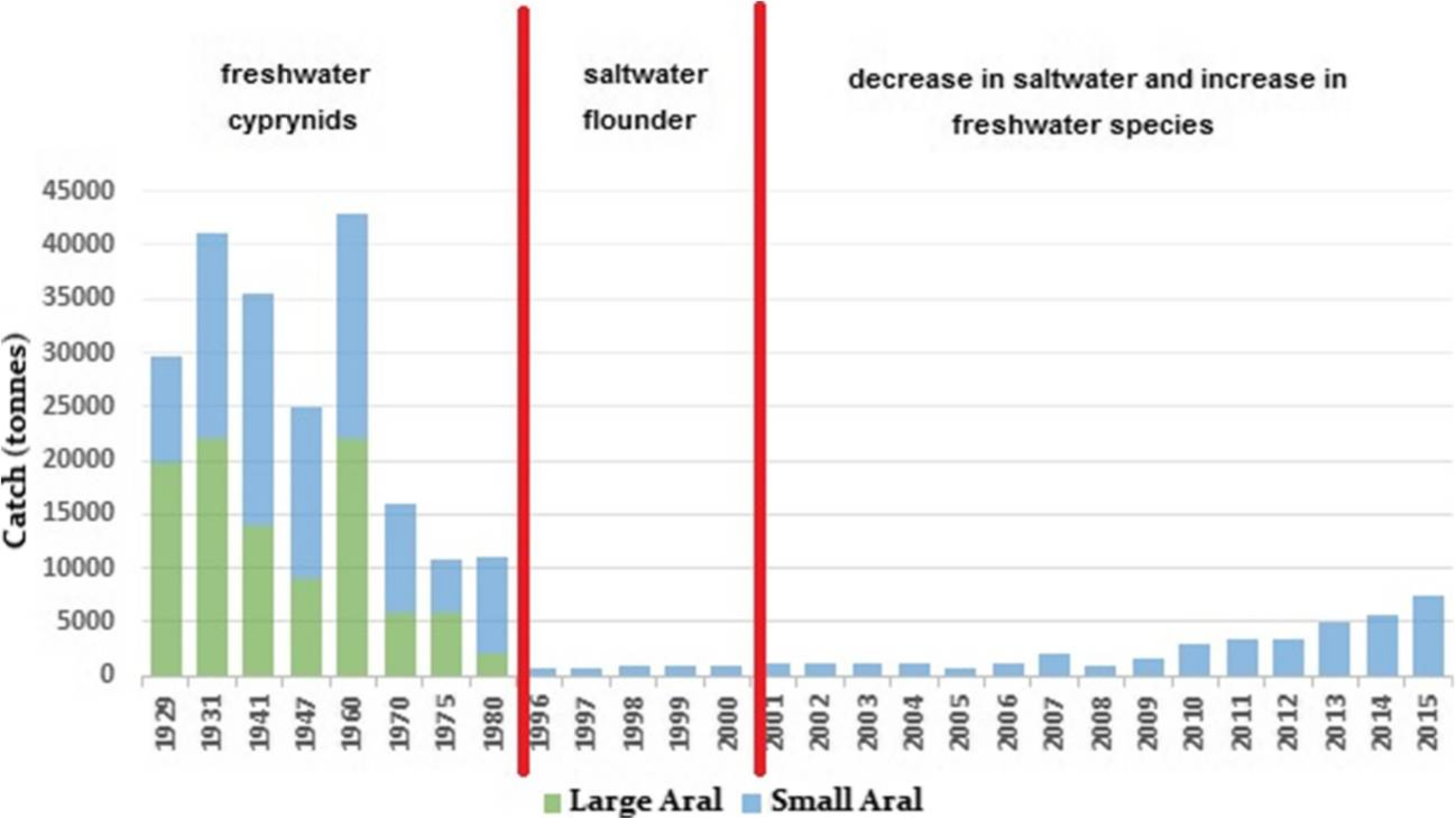

For a decade, the water level held relatively stable, but the salinity steadily increased, crossing the biological boundary between fresh and brackish water of 13 ppt in 1970, causing most freshwater species to go extinct. This was not only fish, but also invertebrates such as cockles, mussels, snails, worms, and especially plankton, including copepods (tiny shrimp), water fleas, and rotifers.

In 1974, the northern Syr Darya was completely dammed, and by 1982 the southern Amu Darya was dammed as well, resulting in the Aral Sea receiving zero inflow from 1982 to 1985. While salinity continued to steadily rise, the brackish water-adapted animal population stayed the same, though all fishing stopped in 1980.

By 1987, the lake had crossed the second salinity barrier between brackish and saltwater concentrations, at 32 ppt. Brackish water species went extinct, leaving only euryhaline and marine species. By 1990, the shrinkage was enough to completely separate the North (or Small) Aral from the South (or Large) lake. Flow into the North Aral from the Syr Darya river had resumed in 1988 (I’m not sure how, I couldn’t find any mention), so with the separation, the salinity and size of the North Aral stabilized while the South Aral continued to shrink and get saltier. To try to maintain the North Aral situation, locals built an earthen dam between the two lakes, known as the Kokaral Dike. This dam was overflowed, destroyed, and rebuilt numerous times until 2004, when the World Bank provided funding to construct a sturdier dam. With the freshening of the lake, the saltwater species that had been there became extinct, but freshwater species from the flow of the Syr Darya soon took up residence. Fishing resumed in 1996 and the total catch has steadily been recovering, though to nowhere near the Aral Sea’s previous level of productivity.

In 1996, the South Aral crossed the third salinity barrier of 50 ppt, becoming a briny environment. Even marine species couldn’t live there anymore, and only the most halophilic (“hal” = salt, “phil” = love) organisms remained, such as nematodes, certain zooplankton and microbes, and a couple species of non-commercial fish. In 2003, the South Aral further split into a deep, skinny western basin and a broad, shallow eastern basin. Neither was connected to the Amu Darya, so they both continued to recede and salinify. By 2014, the shallow eastern basin had completely dried up, leaving extensive salt flats. This image made the news but didn’t seem to trigger any policy change or outcry over the lost sea.

Since the Aral Sea has no river outlets, any pollution that enters dissolves in the water or settles to the bottom. Now that most of the lakebed is exposed, those pollutants are eroding off in the wind and causing health and developmental issues in the surrounding areas. The lack of moisture evaporating off the eastern basin also reduces precipitation in the area, forming a local dust bowl.

Prior Ecological Disturbances (1954-1970)

The story of the Aral Sea isn’t only about changing salinity and water levels. Since the early 1950s, all kinds of foreign fish and invertebrates have been introduced to the lake for one reason or another, or by accident. In 1954, the Baltic herring was introduced as a commercial fish. It is an obligatory planktophage, which hadn’t existed in the Aral Sea before, and it killed 90% of the plankton, before reducing in numbers severely due to lack of plankton. The native plankton in the Aral Sea were slow reproducers compared to plankton that evolved alongside planktophages like the Baltic herring, so in 1965 a new planktonic copepod, which reproduced six times faster, was introduced to replace the ones the herring ate. This sort of worked, but at the same time, larvae of the North American mud crab were simultaneously introduced on accident.

In 1954, fishermen attempted to introduce Caspian mullet, a commercial fish, but it didn’t take; instead, they accidentally introduced a new type of shrimp and five new types of non-commercial fish. Whoops.

Finally, in 1979, when the North Aral was brackish and the freshwater fishing haul was dwindling, a marine flounder was introduced to aid the fishing industry. It was fished in low numbers for five years before the North Aral freshened again and extirpated the flounder.

While all this accidental and intentional introduction of invasive species seems extreme, the effects have been short-lived due to the constantly changing conditions. Even before humans started messing with the Aral Sea, it had lower than expected biodiversity, probably because of its volatile history. However, there are three species of small sturgeon endemic to the Aral Sea and its tributaries that are critically endangered or extinct. Sturgeon, like salmon, are anadromous (“ana” = up, “drom” = run), meaning they migrate upstream to lay their eggs. (The opposite is catadromous (“cat” = down, “drom” = run), like the European eel, which migrates from its adult home in European lakes all the way to the Sargasso Sea to reproduce.) With the complete damming of the rivers in the 1980s, even if the sturgeon had not perished due to the drastic change in salinity, they were unable to reproduce. Sturgeon are long-lived, though, so it’s possible that there are a couple individuals still hanging on, but unlikely that the species will recover even now that the Syr Darya and North Aral have stabilized.

This is the critically endangered Amu Darya sturgeon, photographed in 1982. I’m not sure what these sturgeons use their whiplike tail fin for. The Syr Darya sturgeon is similar but had a more shovel-like nose, and is probably extinct.

Regression during the Little Ice Age (1558-1670)

Now that the lakebeds are completely exposed, it’s easier to tell where old shorelines used to be, and to piece together the story of the lake’s rise and fall and the reaction of the local people over history and prehistory. The next most recent time that the lake regressed substantially was in the 15- and 1600s, during the period known as the “Little Ice Age”, a few hundred years of colder-than-average global temperatures. Multiple factors contributed to the Little Ice Age, such as a solar minimum (the sun producing less radiation than normal); increased human agricultural activity, which increases the brightness of the land, which absorbs less solar energy; and poorly-timed volcanic eruptions that blew particles into the air that blocked additional solar radiation. PBS Eons has a good episode on the Little Ice Age and the people who lived through it.

The result of the Little Ice Age was increased amounts of water stored in polar and Himalayan ice, causing sea levels to drop and creating more arid conditions worldwide. There was also potentially less snowmelt to feed the Aral Sea’s tributaries. In addition, since the Aral Sea is near the Himalayas, which are still growing taller as India tectonically shoves further into Asia, the area is subject to substantial uplift, up to 12 millimeters per year. Over just a few years, this can change the course of rivers, and during the Little Ice Age the Amu Darya, the southern river, was bypassing the Aral and flowing all the way into the Caspian Sea.

Even with only one reduced river feeding it, though, the Aral Sea water level only reached a low of a little over 40 meters above sea level, approximately the level the lake was at in 1989, shown above. (The lake’s highest capacity is 54 meters above sea level.) At that level, while it represents a significant loss of water volume, not a lot of new lakeshore is exposed, so the locals were likely not too badly affected. One record-keeper of the time noted that the Amu Darya changed course again in 1573, beginning to raise the lake level; but since the Little Ice Age was still in full swing, it took another century to fully refill.

Medieval Desiccation (900-1400)

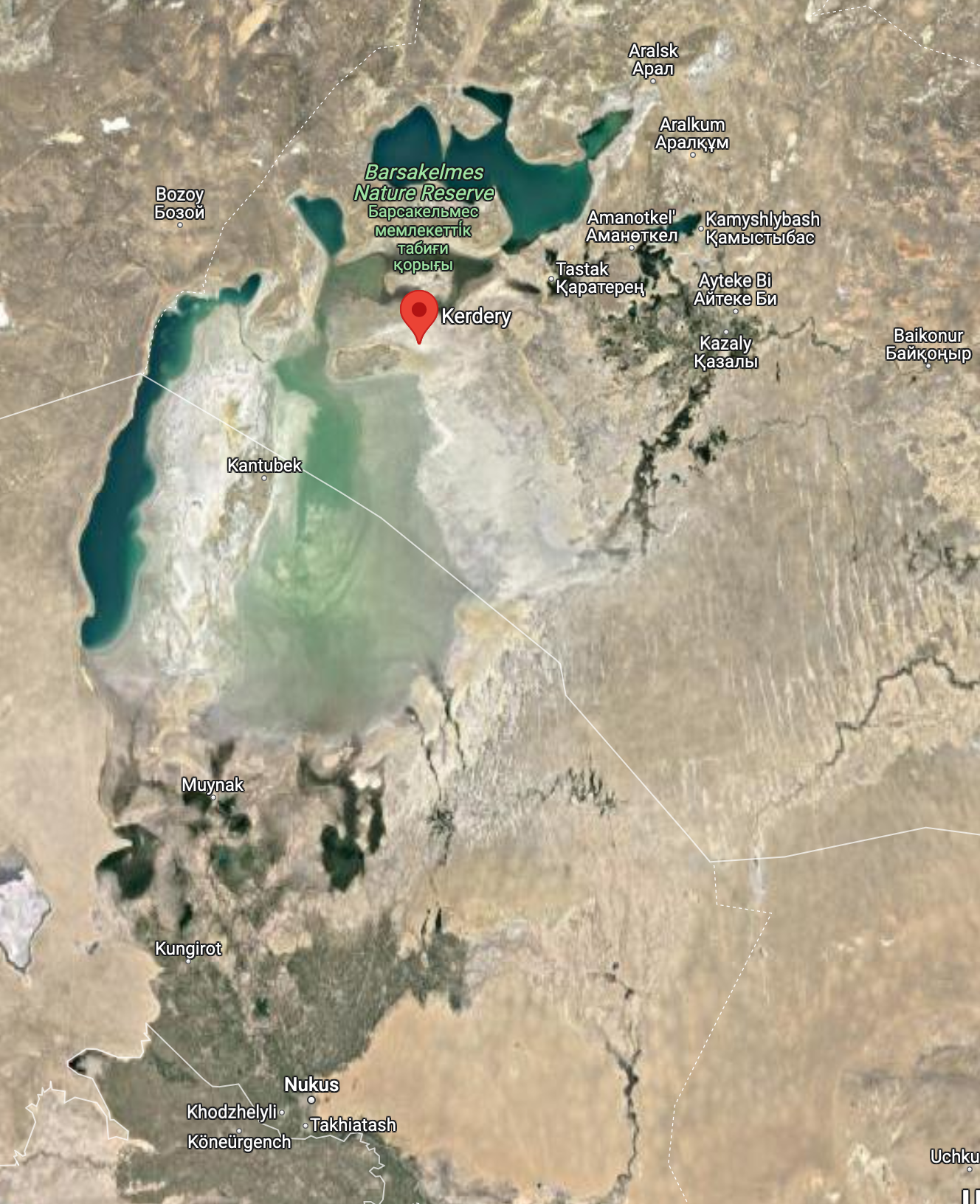

Surprisingly, the lowest level the Aral Sea reached in human history wasn’t in the modern era, but in the Middle Ages. Now that the water level is low again, archaeologists have discovered medieval structures on the lakebed, surrounded by additional settlements that are still flooded and inaccessible. One recently-exposed structure is the Kerderi Mazar, dated from the 1200s to 1300s, a type of Islamic mausoleum. It’s located on a small rise in the northern part of the eastern basin:

(Since the dramatic bone-dry satellite photo from 2014, the shallow eastern basin has received spillwater from the North Aral and subsequently dried again many times. Right now it appears to have water in it.)

The Kerderi Mazar has super-thick stone walls, between one and two meters thick in all places, and a foundation made of stone slabs. This kind of heavy-duty construction is unusual for Central Asia, and that, along with the fact that even the village houses had stone foundations, indicates that the village was relatively prosperous and that the builders knew something about building on unstable, silty lakebed. Nine graves buried in the Muslim style were uncovered around the mausoleum. I’m not sure if there are additional graves to be found or if there were only nine in total, which seems like not very many for an entire mausoleum. Some farming implements had been stashed in a jar in the corner, possibly left by someone who was evacuating when the water levels began to rise in the hope that they could come back for them later.

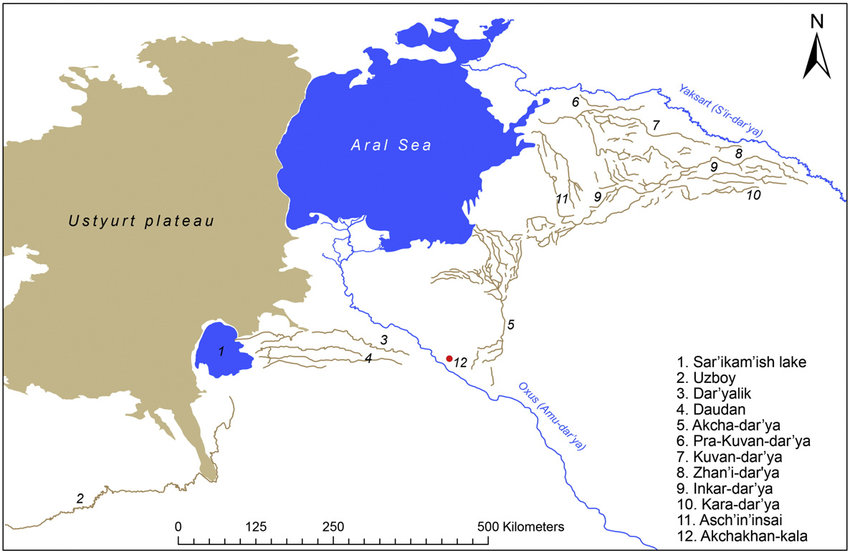

At this time, the North Aral existed and was fed by two rivers, the Syr Darya and an additional river that no longer exists. This village was located relatively close to the banks of the North Aral, and probably used it for fishing and irrigation. Due to the constantly shifting geology, many additional river branches and rivulets have come and gone over time. Since medieval maps are fanciful and inaccurate, it’s difficult to determine the identity of the extra river, but here’s a map showing all the other rivers and routes that have existed in the area, that we know of.

Many of these dry riverbeds have archaeological remains of settlements along them. I think this kind of landscape is super interesting–it’s so inhospitable further from water sources that when the water changes direction, the settlers must follow; and it’s so large that the settlements rarely overlap. It’s as if the fossil record of this place is stratified horizontally rather than vertically!

Historical documents from the time claim that Genghis Khan appeared on the scene in 1221 and destroyed a dam on the Amu Darya, changing the course of the river. However, shortly afterward, the dam was reconstructed, and the event didn’t end up having an effect on the water level. It’s just an interesting tidbit.

I wonder what the medieval people who settled on the lakebed thought. Did they have no idea it was a lakebed? They knew enough to build their buildings differently on it, but not enough to not choose a floodplain to build expensive buildings on.

It’s thought that the cause of this severe regression was again human agriculture; medieval remains of dams along the rivers and dry riverbeds are common, but the situation hasn’t been reconstructed fully.

Ancient History Around the Lake

Artifacts and remains of settlements have been found in the Aral Sea area going back to the Paleolithic (48,000 to 33,000 BCE). There are 219 individual archaeological sites surrounding the lake, and many of them were discovered quite recently due to the modern lake regression. Not much is known about the water level that far back, since tectonic activity has been pushing pieces of shoreline around, and where a stratum lies now isn’t representative of where it once was. (It was previously thought that the sea once filled to a height of 73 meters above sea level, but now it’s believed that those layers were elevated later.) However, scientists can draw some conclusions based on the preservation and modern elevation of the sites. All the Paleolithic sites contained large stone tools that would have been used for hunting large prey–perhaps they didn’t have the technology to fish yet, and since this was the Ice Age on the Mammoth Steppe (a story for another post), large prey was abundant, including mammoths, horses, bison, reindeer, and woolly rhinos. These sites had never been buried by wind-blown sediment or flooded, and were found along a dry riverbed that was probably flowing at the time. The environment was arid but grassy and extremely productive, with dense populations of large animals, like a cold version of the modern African savanna.

After that, there’s an unexplained 28,000 year gap in the archaeological record, before there are signs of Neolithic settlements (5000 to 7000 BCE). Technology had improved, with harpoons and small projectile tips commonly found, indicating that the locals were fishing and hunting small game. Some of these sites also follow a dry river, while others form a ring around a small dry basin. The climate at this point was similar to today’s, but perhaps a little more humid.

The next sites, from the Early Bronze Age (3000 to 1000 BCE), demonstrate another shift in both technology and climate. The predominant weaponry consisted of large arrowheads specialized for hunting horses, and the climate at the time was more forest than steppe. It’s at this point that scientists can start estimating the ancient water level, and during this time it was thought to be somewhat lowered, around 40 meters above sea level. The reason for this is unknown.

During the Iron Age, between 700 and 400 BCE, the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire expanded to the southern banks of the Aral Sea and intensified irrigation in the area, causing another middling water level drop. This was the first time humans drained the lake, but certainly not the last.

Finally, in Late Classical Antiquity (0 to 500 CE), another human-intensified water level drop occurred. Extensive canals and dams on both the Amu Darya and Syr Darya date to this period. However, at this time, the Amu Darya was running an alternate route along the Uzboy streambed and draining into the Caspian Sea, which also contributed to the lake regression. The timeline is summarized below:

Conclusion

With this kind of tumultuous history, it’s no wonder that the Aral Sea’s native fauna wasn’t very diverse when scientists started keeping track of it–everything routinely seems to become extinct every few hundred years. However, we’re currently in what would naturally be an Aral Sea maximum, and the fact that the water level is instead extremely low is a testament to Soviet engineering.

On one hand, the area closest to the lake is currently very inhospitable due to aridity and pollution, though people still do live there and fish in the North Aral. On the other hand, irrigation and power from the lake’s tributaries are necessary to grow food and keep the lights on in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and many of the other -stans. On the other other hand, Uzbekistan’s agricultural workforce has historically been made up in no small part by forced laborers, and the cultivation of cotton especially has salinified the soil, preventing other crops from thriving. There are a lot of pros and cons to any course of action involving this troubled sea, and its future is uncertain.

Just For Fun: Pink Lakes And Unkillable Halophiles

While I was researching this obscure lake, I also learned about two weird natural phenomena I hadn’t heard of. Did you know that salt lakes sometimes turn pink?

Apparently this is pretty common, and it’s safe to swim in such lakes, although it’s not recommended to drink (mostly just because they are usually very salty). The pink color comes from halophilic, photosynthetic algae, bacteria, and archaea, which create beta-carotene, the pigment that makes carrots orange. These organisms can live in conditions of up to 350 ppt salinity, ten times as salty as seawater! Beta-carotene helps to protect them from radiation, similarly to how animals and fungi use melanin. The combination of orange beta-carotene and green chlorophyll apparently creates this lovely cotton candy color.

Did you know that bacteria can survive in stasis for at least 250 million years? A halophilic bacterium that formed a protective spore casing around itself was preserved in liquid brine inside a rock from 250 million years ago–the dawn of the Age of Reptiles. Scientists were able to isolate it and grow it on a petri dish, and it came alive like nothing had happened. To eliminate possible contamination with modern bacteria, the researchers carefully chose a sample that they could verify was undisturbed for the entire time, treated all their equipment with many types of harsh sterilization techniques, and then, once they had a steady population of the ancient bacterium, treated it with the same harsh sterilization techniques and confirmed that it did indeed die (meaning it wasn’t a modern bacterium resistant to sterilization). I’m still pretty skeptical that something like this could happen, but now that it’s been tried, other researchers will probably attempt similar feats, and the facts will shake out. Science!

Image Credits

High and low water levels Current water level Amu Darya sturgeon Kerderi mausoleum Mammoth steppe

References

[1] Aladin, N. V., Gontar, V. I., Zhakova, L. V., Plotnikov, I. S., Smurov, A. O., Rzymski, P., & Klimaszyk, P. (2019). The zoocenosis of the Aral Sea: six decades of fast-paced change. Environmental science and pollution research international, 26(3), 2228–2237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-3807-z

[2] Krivonogov, S.K. Extent of the Aral Sea drop in the Middle Age. Dokl. Earth Sc. 428, 1146 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028334X09070241

[3] Boroffka, N. G. O., Obernhänsli, H., Achatov, G. A., Aladin, N. V., Baipakov, K. M., Erzhanova, A., HöRnig, A., Krivonogov, S., Lobas, D. A., Savel’eva, T. V., & Wünnemann, B. (2005, January). Human Settlements on the Northern Shores of Lake Aral and Water Level Changes. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 10(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-005-7831-1

[4] Voyakin, & Krivosheev. (2008, May 20). Mausoleum of Kerderi. silkadv.com. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://silkadv.com/en/content/mausoleum-kerderi

[5] Moore. (2021, April 20). How To Survive the Little Ice Age. YouTube. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-YLTbm2GNQ

[6] Boroffka, N., Oberhänsli, H., Sorrel, P., Demory, F., Reinhardt, C., Wünnemann, B., Alimov, K., Baratov, S., Rakhimov, K., Saparov, N., Shirinov, T., Krivonogov, S. K., & Röhl, U. (2006). Archaeology and climate: Settlement and lake-level changes at the Aral Sea. Geoarchaeology, 21(7), 721–734. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.20135

[7] Vreeland, R., Rosenzweig, W. & Powers, D. Isolation of a 250 million-year-old halotolerant bacterium from a primary salt crystal. Nature 407, 897–900 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35038060

[8] Dodson, J., Betts, A., Amirov, S., & Yagodin, V. (2015, November). The nature of fluctuating lakes in the southern Amu-dar’ya delta. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 437, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.06.026