Becoming a fossil is a long and difficult journey. The organism has to die and be buried before scavengers and decomposers get at its body, it needs to avoid being crushed or melted through tectonic or volcanic activity, and then it must be eroded or lifted to the surface for scientists to find. With all these necessary and unlikely steps, it’s not surprising that a tiny minority of all organisms that have ever lived end up in fossil collections–only a tenth of a percent of all species is estimated to enter the fossil record, and a fraction of that actually gets found. Luckily for science, though, billions upon billions of organisms have lived and died throughout the history of the earth, so fossils are relatively common. However, the types of organisms we find fossils from aren’t necessarily representative of the population that lived in that time and place. The process of fossilization and discovery favors certain organisms over others in systematic ways, known as preservation bias and sampling bias. In this post, I’ll go over how these biases affect our interpretation of the ancient world and how scientists attempt to overcome them.

It’s important to note that even if we dug up and catalogued every single fossil that’s available on the earth’s surface, there would still be gaps in our knowledge of ancient life. Fossil sites tend to preserve only a small slice of time in a particular place, so we can’t know what was in that place throughout the rest of history. There are also many places and times that are not represented at all. All we can do is try to figure out what we’re missing, and compensate for it when using fossil datasets.

Preservation Bias

There are two main factors that influence preservation bias: the abundance of the organism in its environment over time, and the likelihood the organism preserves. If the organism is very common in its environment, and if it persists for a long span of geologic time, there are more chances for individuals to be preserved. The likelihood of individual preservation has more variables affecting it, such as

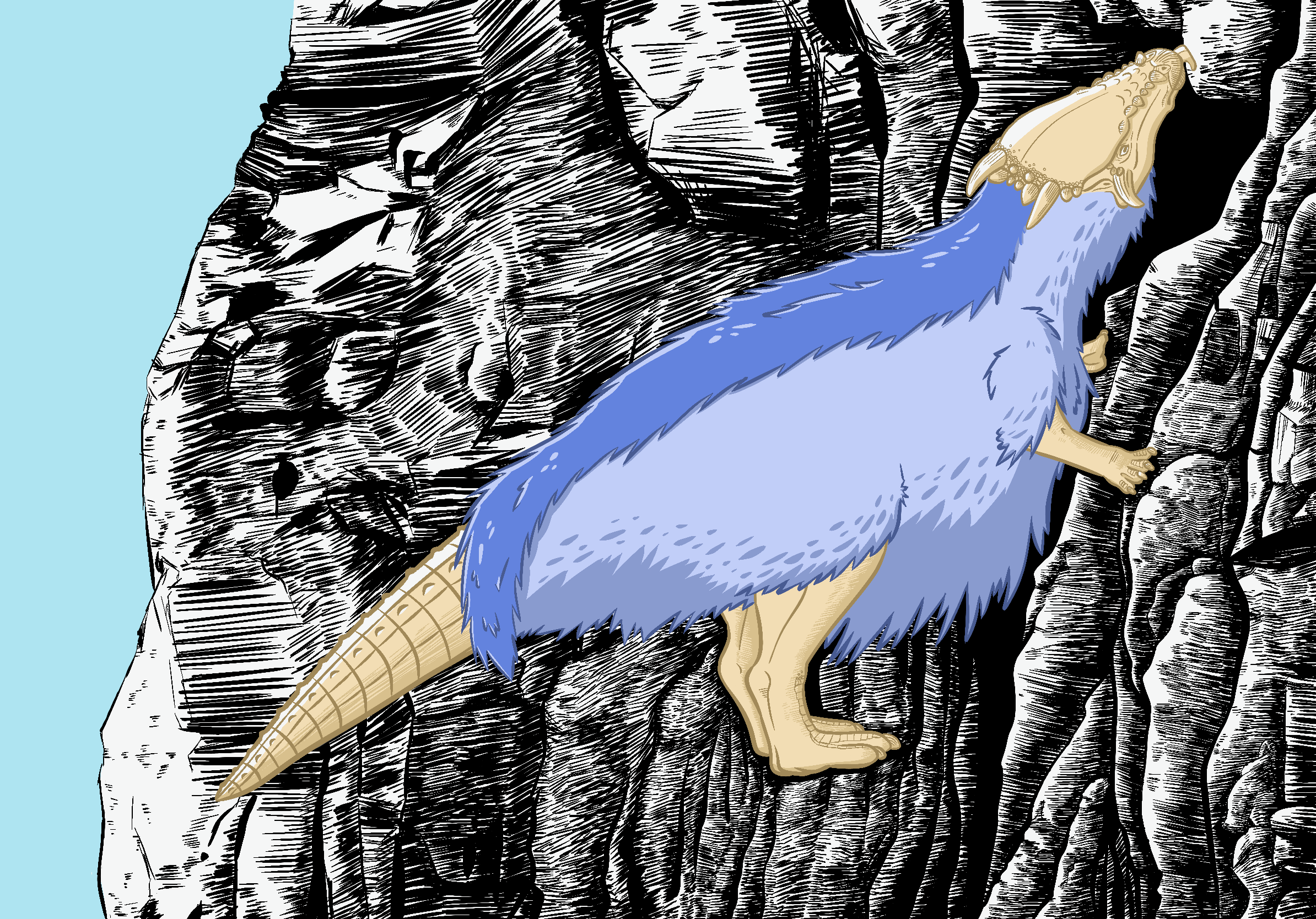

- Type of habitat: Environments where sediment is deposited and not disturbed produce more fossils than ones where sediment is being eroded off or regularly disturbed. For example, ancient lakes and seas, where silt is constantly entering through rivers, sinking, and piling up, are great places to find fossils, while rainforests, where the soil is disturbed by plants, burrowing animals, and fungi, and mountaintops, where the ground is eroding off rather than collecting more sediment, don’t often produce fossils. This is why I drew a mountain-climbing pachycephalosaur for the page image: nothing like that is known to have existed, but we would expect not to find it even if it did! In general, marine and lake-dwelling organisms preserve more often than terrestrial or river-dwelling ones.

- Hard vs soft bodies: Organisms with mineralized body parts, such as bones, shells, and armor, are much more likely to preserve than entirely soft-bodied or unmineralized ones. For example, the calcified shells of clams are much more likely to preserve than the proteinaceous exoskeletons of insects, even though in life insect shells seem sturdy. A flatworm has an even smaller chance of being fossilized than an insect.

- Age: The older a fossil is, the more likely geologic processes will have destroyed it, such as subduction (the rock containing the fossil sinks into earth’s mantle), weathering and erosion, metamorphic activity (the rock containing the fossil is pressurized and heated until the fossil isn’t recognizable), glaciation, or burial by younger sediments. At the bottom of the ocean, the oldest rocks are Triassic or Jurassic in age, since ocean crust is always being pushed like a conveyor belt underneath continental crust. The oldest continental crust is almost as old as the earth itself–4.4 billion years–and the oldest oceanic crust is only 200 million years old. That’s over twenty times younger!*

- Type of sediment: The chemical and physical interactions between the substrate itself and organic remains can favor some organisms over others. If the grain size is too large, tiny organisms might not be recognizably preserved, and if it’s exposed to acidic or basic conditions, different organic materials will dissolve away.

*Note: Some parts of the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea are older than this, possibly up to 340 million years old. However, that’s not oceanic crust, but continental crust that happens to be underwater, and it’s also still over ten times younger than the oldest continental crust.

Other factors can also affect the quality of preservation. Some fossils are articulated (all the body parts in their correct relative positions) while others are scattered, due to water flow, wind, or scavenger activity. Some preserve soft tissues or their impressions depending on mechanical and chemical considerations, while most only show the bones and shells.

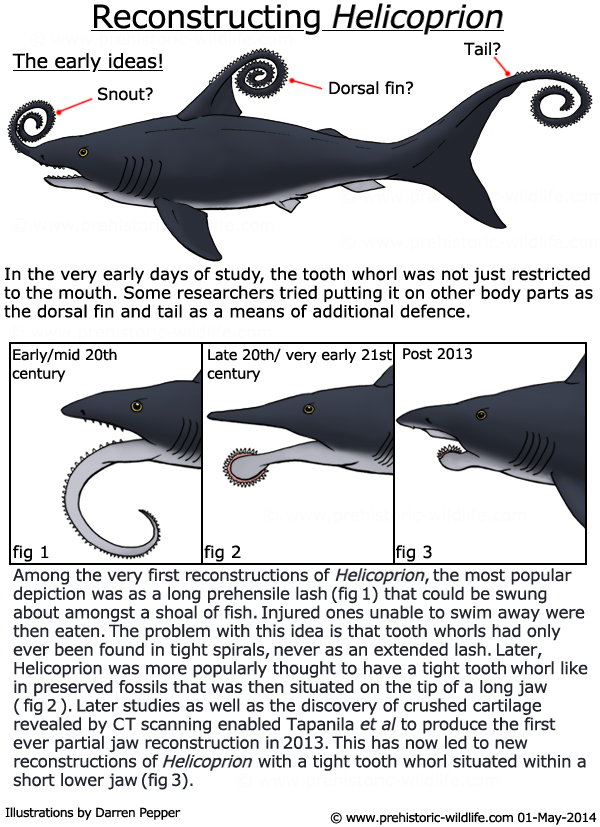

Sometimes, only a particular body part repeatedly makes it into the fossil record, because it’s the hardest or most abundant tissue. For example, shark and dinosaur teeth are extremely common fossils, since their owners continuously replaced them in life. However, that kind of disposable tooth doesn’t usually have unique characteristics that can tell scientists much about the animal. Sharks in particular commonly leave only teeth, since their skeleton is made of soft proteinaceous cartilage while the teeth are mineralized. A famous example is the Helicoprion tooth whorl:

Dozens of these tooth spirals have been unearthed with no body to connect them to, until 2013, when CT scanning a specimen revealed a preserved cartilaginous skull, finally putting to rest the debate of where the heck the whorl belonged on the body.

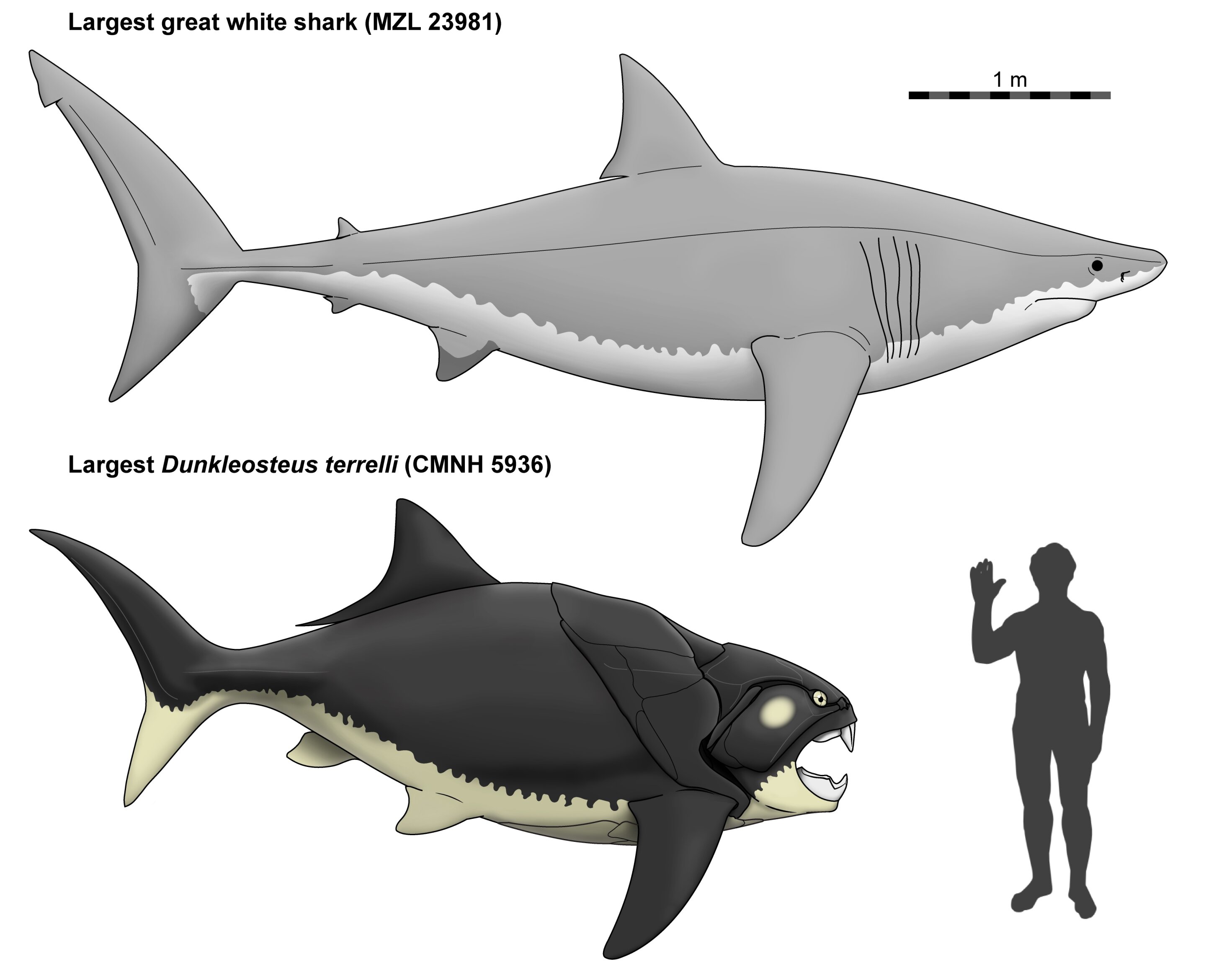

Another example that was in the news recently is the “Dunk Shrunk” paper. Dunkleosteus was a huge predatory armored fish from the Devonian Period (382-358 million years ago). It was a member of the placoderms, a group of fish that had cartilaginous internal skeletons like those of sharks, but bony exoskeletons on their faces and front part of their bodies. As a result, the face and chest armor are the only body parts known from most placoderms. Until recently, Dunkleosteus, the largest predatory placoderm, was thought to be similar in size and shape to a great white shark. However, a recent paper that utilizes a new body length estimation technique paints a very different picture:

A hydrogen-bomb-shaped fish, a shape like that of no fish today! People are calling it “Chunkleosteus”.

Similarly, the famous giant shark Megalodon is known only from jaws and teeth. Who’s to say it wasn’t a modest-sized shark with a giant mouth? For pachycephalosaurs, or dome-headed dinosaurs such as the one in the page image, the cranial dome is usually the only thing that preserves.

A somewhat opposite source of bias is the presence of Lagerstätten, or fossil sites that boast exceptional preservation, such as the Yixian Formation (Early Cretaceous) and the Messel Pit (Eocene). These sites contribute disproportionate numbers of well-preserved fossils to the record, which makes it look like there’s higher diversity and morphological disparity (differentiation in body shapes) at that time. However, for certain organisms that have delicate bodies, such as pterosaurs (flying reptiles) and bats, Lagerstätten are the only places that they preserve, which means that statistical analyses can’t omit those fossil locales without deleting entire lineages.

Sampling Bias

Whether or not a fossil gets noticed is the final barrier to entering the scientific record. Microfossils like pollen, snake vertebrae, and microorganisms often fail to be collected, since to find them every cubic inch of dirt must be sifted. Some fossil sites, like the Gray Fossil Site in Tennessee, sieve everything that’s excavated as normal procedure, but most sites don’t have this luxury. Either the conditions are too hostile to stay long, or are only permitting at certain times of year; or there’s not enough funding for scientists to do this labor-intensive work; or there’s just too much dirt to possibly look at all of it. This is an unfortunate fact, since microfossils can be very informative, and once the fossiliferous dirt has been excavated it’s difficult to know where any later discoveries originally came from.

A special case of noticing fossils is in trackways, or ancient footprints. Some animals have a center of mass closer to the front or back feet, or they have differently-shaped front and back feet, such as in hadrosaurs (“duck-billed” dinosaurs) and sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs), both of which had bony, narrow front feet and broad, padded back feet. That means that in some conditions, only a sauropod’s front footprints are preserved, or its back prints are present very shallowly and can easily weather off or be overlooked, leaving a trackway that looks like it was doing a handstand. In other cases, depending on the type of mud the dinosaur was walking on, hadrosaurs’ front prints can fail to preserve or be noticed, leaving a trackway that looks similar to theropod (bipedal, carnivorous dinosaur) prints, leading to confusion in classification. Furthermore, particular types of mud will only allow particular sized footprints to form, as too-small animals won’t indent the surface while too-large ones would become mired and avoid the area. Therefore, trackways usually preserve the footprints of only one size of animal, even though others may have been present as well, meaning herd or social behavior is very difficult to identify from tracks.

Another barrier to discovery, even before the fossil getting noticed, is the environment that’s there now. Thick ice like in Antarctica, rainforests, or deep water can make it very difficult to dig, and impossible to know where to dig. That’s why so many fossil finds come from modern badlands: it’s where fossils are being exposed at the surface by natural erosion, so you can just walk around and see them.

There’s also the fact that most paleontologists have historically hailed from the United States and western Europe, and digging near your home is easier than going far afield. A vast majority of fossils in the scientific record, therefore, come from these two locations. This introduces multiple forms of bias: obviously, the diversity of life in those places is going to appear higher than elsewhere, but also, the fact that the tectonic plates containing Europe and North America have mostly followed each other in latitude over geologic time means that tropical organisms are overrepresented from the Paleozoic, while temperate ones are overrepresented in the Cenozoic. When researchers are trying to find patterns in the distribution and types of organisms over time in order to detect extinction events and evolutionary trends, systematic biases like these can cause problems. We also don’t have records of people looking for fossils and failing to find any. Those kind of results don’t get published to become part of the scientific corpus, but excluding them also causes statistical issues.

The last important factor affecting sampling bias is whether paleontologists are interested in a topic. Charismatic megafauna such as dinosaurs and other large vertebrates draw a lot more attention than plants, microbes, and invertebrates. Some scientists have attempted to quantify this by going through lists of paleontological faculty and published authors, noting what they work on, and assigning “paleontologist interest units” to topics, but this is hard to apply, or of questionable value, to statistical models. However, it certainly has an effect on what is studied and what is forgotten.

Overcoming Bias

Despite all these challenges, scientists have come up with a few different strategies over the years for correcting for these biases. First, as I stated in the introduction, a complete fossil record, in which scientists have catalogued every available fossil, would still be an incomplete catalogue of ancient life. However, through surveying and mapping the entire earth’s exposed geology and extrapolating the kinds and density of fossils found in particular types of rock formations, we can get an idea of what a theoretic complete fossil record might look like, and then compare where we actually are to the theoretic ideal. If we know how close to complete the record is for a certain lineage, we can better guess how much morphological disparity and species diversity is missing, and when the lineage arose and how long it persisted.

In large datasets, statistical tricks such as subsampling can be used to reduce the impact of sampling and preservation biases. This involves designating “time bins” of equal size from which a designated number of fossils are randomly drawn to include in the study, so bins containing lots of fossils are reduced to the same size as ones with few fossils. Strategies like this are getting more and more popular as statistical packages get more sophisticated and public databases like the Paleobiology Database get larger and more comprehensive. However, this approach only works if your fossil-poorest bins still contain a statistically robust number of samples, which isn’t the case for many organisms.

Another way to estimate how incomplete your dataset is is through genetic analysis. If the molecular clock estimates that a lineage arose x million years ago, but the first fossil occurrence is x minus y million years old, there’s an implied gap of y million years. Do this to a lot of lineages, and you can use the average gap size as a measure of record incompleteness. You can also use sister taxa, or the closest relative to a group, to infer the true earliest appearance of a lineage. For example, fragmentary fossils from rhynchocephalians (tuatara and relatives) were known from 240-238 million years ago, but until recently the oldest squamate (lizards and snakes, the closest living relatives to tuatara) fossil was much younger than that. However, we can infer that since rhynchocephalians existed, their sister group the squamates should also exist, and indeed in 2018 the re-analysis of a fossil lepidosaur called Megachirella declared it the earliest known squamate. Even if we aren’t lucky enough to actually find the inferred fossil, knowing it should exist is a useful implication.

A very practical method of overcoming bias is to simply put seashells or other remains in a tumbler, and observe how and which things get destroyed in what order. This simulates the action of ocean waves or river flow, and can give scientists an idea of what to expect to find and to not find under different preservation conditions.

A final way to reduce sampling bias is to go to less-studied locations and collect fossils! Or even better, to support efforts in these areas for locals to gather and study fossils. While many of the above biases are unavoidable due to the way fossils are formed and discovered, location-based and paleontologist interest-based biases aren’t inherent, and can be corrected through spreading awareness and support.

Overall, more and more fossils getting added to the archive as science marches on will help increase scientific understanding of ancient life, but since all fossils are subject to systematic and unavoidable biases, we need to continue to be aware of and attempt to correct for these biases in scientific study. Larger datasets will make this easier, but it will always be a necessary step to achieve accurate estimates of ancient diversity and disparity.

References

[1] K. (n.d.). Preservation Bias in the Fossil Record – Laboratory Manual for Earth History. Preservation Bias in the Fossil Record – Laboratory Manual for Earth History. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/earthhistorylab/chapter/preservation-bias-in-the-fossil-record/

[2] Castanera, D., Vila, B., Razzolini, N. L., Falkingham, P. L., Canudo, J. I., Manning, P. L., & Galobart, N. (2013, January 22). Manus Track Preservation Bias as a Key Factor for Assessing Trackmaker Identity and Quadrupedalism in Basal Ornithopods. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e54177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054177

[3] Falkingham, P. L., Bates, K. T., Margetts, L., & Manning, P. L. (2011, January 13). The ‘Goldilocks’ effect: preservation bias in vertebrate track assemblages. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 8(61), 1142–1154. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2010.0634

[4] M. J. Benton, G. Wm. Storrs; Testing the quality of the fossil record: Paleontological knowledge is improving. Geology 1994;; 22 (2): 111–114. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1994)022<0111:TTQOTF>2.3.CO;2

[5] Maxwell, W., & Benton, M. (1990). Historical tests of the absolute completeness of the fossil record of tetrapods. Paleobiology, 16(3), 322-335. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010022

[6] Sheehan, P. (1977). A reflection of labor by systematists? Paleobiology, 3(3), 325-328. doi:10.1017/S009483730000542X

[7] Alroy, J., Aberhan, M., Bottjer, D. J., Foote, M., Fürsich, F. T., Harries, P. J., Hendy, A. J. W., Holland, S. M., Ivany, L. C., Kiessling, W., Kosnik, M. A., Marshall, C. R., McGowan, A. J., Miller, A. I., Olszewski, T. D., Patzkowsky, M. E., Peters, S. E., Villier, L., Wagner, P. J., . . . Visaggi, C. C. (2008, July 4). Phanerozoic Trends in the Global Diversity of Marine Invertebrates. Science, 321(5885), 97–100. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1156963

[8] Benson, R. B. J., Butler, R. J., Lindgren, J., & Smith, A. S. (2009, November 18). Mesozoic marine tetrapod diversity: mass extinctions and temporal heterogeneity in geological megabiases affecting vertebrates. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1683), 829–834. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1845

[9] McGowan, A. J., & Smith, A. B. (2008). Are global Phanerozoic marine diversity curves truly global? A study of the relationship between regional rock records and global Phanerozoic marine diversity. Paleobiology, 34(1), 80–103. https://doi.org/10.1666/07019.1

[10] Flannery Sutherland, J. T., Moon, B. C., Stubbs, T. L., & Benton, M. J. (2019, February 27). Does exceptional preservation distort our view of disparity in the fossil record? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286(1897), 20190091. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0091

[11] Turner, M. L., Falkingham, P. L., & Gatesy, S. M. (2020, July). It’s in the loop: shared sub-surface foot kinematics in birds and other dinosaurs shed light on a new dimension of fossil track diversity. Biology Letters, 16(7), 20200309. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0309