Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell! ….just kidding, that’s not what this post is about. Mitochondria are organelles, tiny structures within each of an organism’s cells, that are responsible for creating ATP, a chemical that can be used as an energy source elsewhere in the cell. Mitochondria are much more interesting than most organelles–they appear to have been, a long time ago, a separate creature than the host cell, that started living inside a larger cell in a symbiotic relationship around 2 billion years ago, and never left. The host cell gets ATP from the mitochondrion, and the mitochondrion gets shelter from the host cell. Even now, mitochondria retain some of their independence, like a recalcitrant startup unhappily acquired by a conglomerate. Mitochondria have their own DNA, separate from the main cell’s DNA that resides in the cell’s nucleus. And this makes it a really useful resource for molecular and evolutionary biologists to look at, since this secret stash of DNA (1) doesn’t experience any evolutionary pressures, (2) doesn’t recombine like cellular DNA does on a regular basis, and (3) is passed from mother to child pretty much intact, save a few small mutations. We’ll expand on this in a bit. But first, let’s back up a little…

The Molecular Clock

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) provides the basis for the “molecular clock.” The idea behind this is that harmless random mutations–ones that don’t provide any evolutionary benefit or detriment–add up at a relatively constant rate over time, and since they’re random, two species that don’t interbreed will slowly accumulate more and more differences in their mitochondrial DNA over time. If you can see how different two creatures’ mtDNA are from one another, if you know the average mutation rate (which in itself is sometimes easier said than done), you can extrapolate how long ago the two creatures shared a common ancestor. This can’t be reliably done with cellular DNA because of a few reasons.

- It’s selected on by evolutionary pressures. This leads to weird scenarios in which two very distantly related creatures can share large swathes of genome. For example, echolocating bats and echolocating cetaceans (whales and dolphins) use the same genes to echolocate, even though they both descended from non-echolocating ancestors and figured out how to echolocate independently.

- It recombines on a regular basis. When sperm and eggs form, their chromosomes undergo “crossing over,” in which bits of the genome will swap places with one another. This is helpful for maintaining genetic diversity (if your kid is a total clone of yourself, there’s less variation for natural selection to work with) but it’s a bummer for molecular biologists trying to keep track of things. Even in creatures that reproduce asexually, like bacteria, bits of cellular DNA can be horizontally transferred from one organism to another.

- It recombines again during sexual reproduction. The mixing of two batches of genetic material makes it really complicated to keep track of where stuff came from.

Mitochondrial Eve

We’ve stated above that mtDNA is passed from mother to child intact. But how does this work? It’s actually not a completely straightforward answer. There are two main factors: (1) somehow the egg actively destroys the sperm’s mtDNA after fertilization, which is a process not fully understood; and (2) most of the sperm’s mitochondria are in the base of the tail anyway (they’re powerhouses! So it makes sense that they’re used for propulsion), which doesn’t actually enter the egg.

Okay, now we’re ready to go into what Mitochondrial Eve actually is. The way it’s commonly stated is that all living humans have the “same” mtDNA, belonging to this mysterious ancient woman, Mitochondrial Eve, who is a common ancestor of all humans alive today. That is a true but misleading statement. Take a look at the tree below:

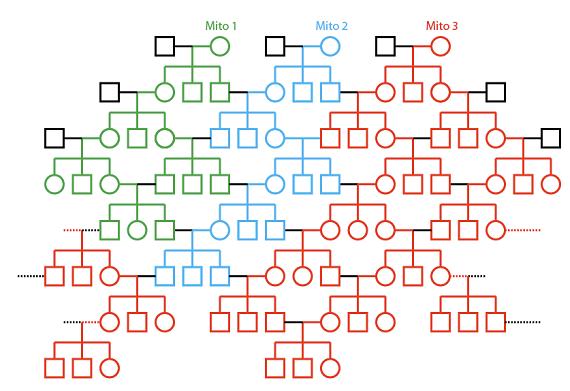

Ignoring the disturbing habit of this family to methodically always marry their first cousins, this tree shows an example of how even as the total population remains large (there aren’t any “bottleneck” events where only two individuals remain), one variant of mtDNA can become ubiquitous while the rest don’t get passed on. Here, the circles represent women and squares represent men. The colors show which type of mtDNA the individual has. Even though the green and blue lines have descendants who live in the present day–in fact, the way this tree is constructed, everyone in the third-to-bottom row and below can count Mrs. Mito 1, Mrs. Mito 2, and Mrs. Mito 3 as their great-great-great grandmothers–at some point their descendants either have only sons or no children, and their mtDNA fails to get passed on. In other words, it’s possible to have living descendants who do not share your mtDNA, if the line of descent includes any sons.

So, if you’re talking about the population alive today who are in the group shown on this tree, Mrs. Mito 3 is their Mitochondrial Eve. The important things to realize are as follows:

- Mitochondrial Eve is relative. There is a Mitochondrial Eve of my extended family (a human who lived in the early 1900s), a Mitochondrial Eve of all living humans (a human who lived a couple hundred thousand years ago), a Mitochondrial Eve of all living apes (an ape who lived a couple tens of millions of years ago), etc. The larger the group under consideration, the farther back in time the Eve lived; but she exists for as long as sexual reproduction existed. Usually when someone is talking about Mitochondrial Eve, they mean the Mitochondrial Eve of all living humans, but that’s just one of many groups’ Eves we could examine.

- Mitochondrial Eve isn’t special. Every Eve was a member of a large population at the time, and she was just another woman in that population. She had no idea that her lineage would be the lucky one that kept having daughters who kept having daughters.

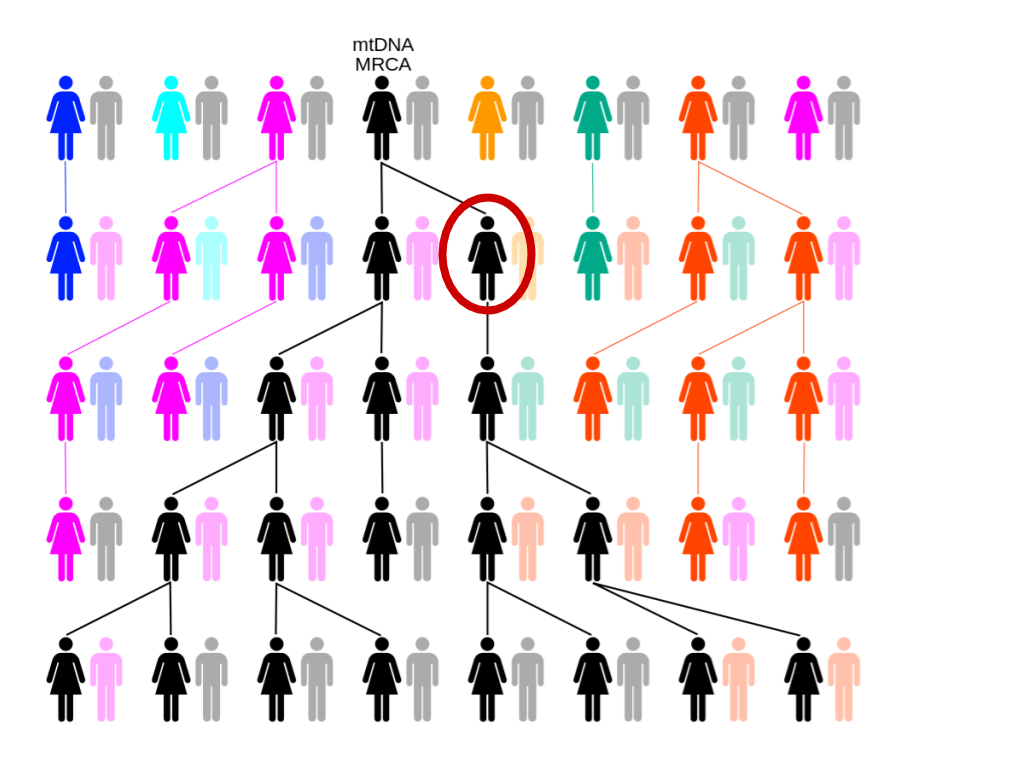

- Mitochondrial Eve can change–the title can transfer to someone more recent. As time goes on and populations die out, it’s possible for the title of Mitochondrial Eve to be confiscated from one individual and bestowed upon another. Let’s look at a somewhat less incestuous tree:

Here, the woman in black at the top holds the title. But just say all four of the couples in the bottom row on the left half go on to have no daughters, only sons or nothing, while some of the couples on the right half of the bottom row do have some daughters. Then half the tree will have been pruned, and the title of Mitochondrial Eve will have passed to the woman in black in the second row on the right (circled).

If I’ve done my job in explaining, at this point you should realize why Mitochondrial Eve is a tautology, or something that exists by definition. Within a sexually reproducing population, every daughter has a mother, but not every mother has a daughter. Because of this, if you trace the current generation’s matrilineal line back far enough, you’ll always reach one woman. But that woman wasn’t special, and her peers also have living descendants, so knowing Mitochondrial Eve’s identity is not actually very informative.

Y-Chromosomal Adam

The male equivalent of Mitochondrial Eve is Y-Chromosomal Adam, since men inherit the Y chromosome from their fathers, but this is harder to track down because the Y chromosome is part of the cellular genome, so it has the complications of recombination and selective pressures outlined above. In overwhelming likelihood, Mitochondrial Eve and Y-Chromosomal Adam lived many generations and many miles apart from each other. Similarly to Eve, Y-Chromosomal Adam didn’t know he was special and will eventually bequeath his title to one of his descendants as more branches of the human family tree fail to have sons.