Dinosaurs and friends, being large and charismatic, have had their fair share of airtime over the years. However, it’s not uncommon for the artists who actually do the reconstructions to be unfamiliar with paleontology and to make errors, and even when a reconstruction is good at its time of release, the field of paleontology moves so fast these days that it can quickly become dated. In this post, I’ll show you some good reconstructions of dinosaurs (and friends) and point out some common pitfalls inexperienced paleoartists tend to make.

Theropods

Above: A recent reconstruction by the Saurian team of The King himself. This is one of the most meticulously-researched reconstructions of Tyrannosaurus ever attempted.

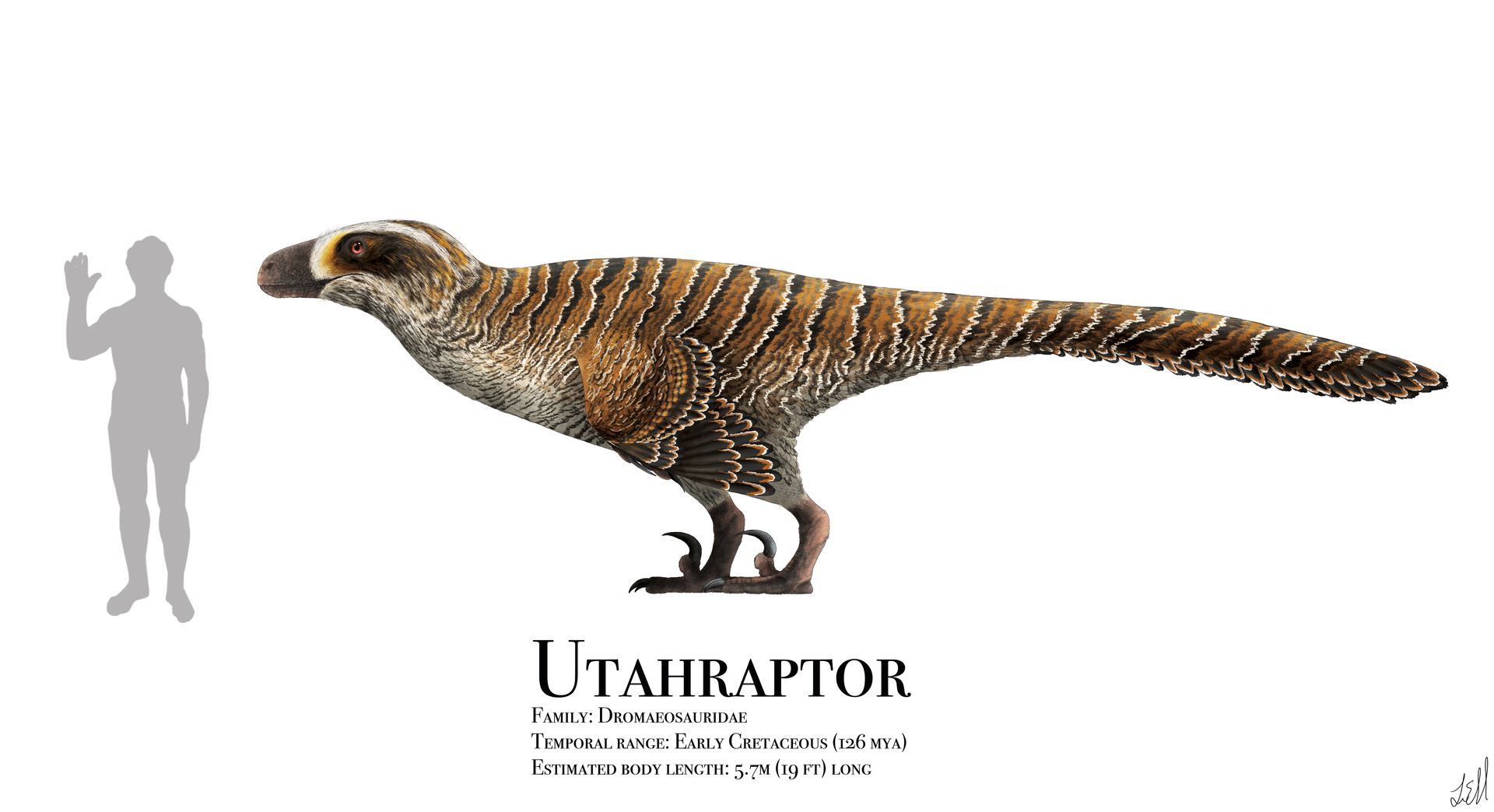

Above: Utahraptor, the largest known dromaeosaur, and a close relative of Velociraptor and Deinonychus.

Here are some key features to note about theropods, in approximate order from most important to least:

- Horizontal posture. The head is about level with the tail. Really old reconstructions (pre-1970s) depicted theropods as having a vertical, kangaroo-like posture with a dragging tail, but based on biomechanical studies and fossilized trackway evidence, this has long been known to be inaccurate.

- Stiff tail. The tail sticks out straight and acts as a counterbalance to the upper body. Many theropods had tails that were stiffened by ossified tendons, which made them unable to bend or curl very much.

- “Clapping” hands. The hands are oriented as if about to break into applause. A common mistake is to orient the hands like the paws of a dog who is “sitting pretty” (I’m not naming any names here). To visualize how theropod (and bird) arms actually bend, hold your hands like you’re about to clap. Now try to rotate your hand downward toward the floor so that your pinkie gets closer to your forearm. We humans can only do this a little bit, but due to the way birds’ (and non-avian dinosaurs closely related to birds’) wrists are constructed, they can lay their fingers basically flat against their forearms in this manner. That’s how birds fold their wings, and how dinosaurs closely related to birds, like Velociraptor, folded their arms. This adaptation was originally useful for preventing long arm feathers from dragging on the ground, but later was improved upon for use in flight.

- Lips. Generally, if you don’t live in the water, you need lips or else your teeth are going to get really dry and painful. Osteological correlates (textures and marks on bone left by the overlying tissue) indicate that this was the case with most theropods. When a theropod’s mouth is closed, the teeth shouldn’t be showing.

- Feathers? The consensus now, based on numerous tiny skin impression fossils from all over its body, is that Tyrannosaurus itself was completely scaly, but this is a derived condition. Many other theropods were partially or completely feathered, mainly maniraptoriformes like Velociraptor, Deinonychus, Troodon, Gallimimus, and Oviraptor. And the feathers weren’t just thin, scraggly fuzz, either–even though many feathered theropods couldn’t fly, they had pennaceous quill-like feathers on their arms and tails that made them look extremely birdlike. Even the biggest dromaeosaurs like Utahraptor probably looked like giant ground-hawks.

- Front-facing eyes. Predators almost always have front-facing eyes because the increased overlap of visual fields provides better depth perception, which is important for catching prey. Prey animals almost always have sideways-facing eyes because the increased field of vision is good for preventing enemies from sneaking up on you.

Sauropods

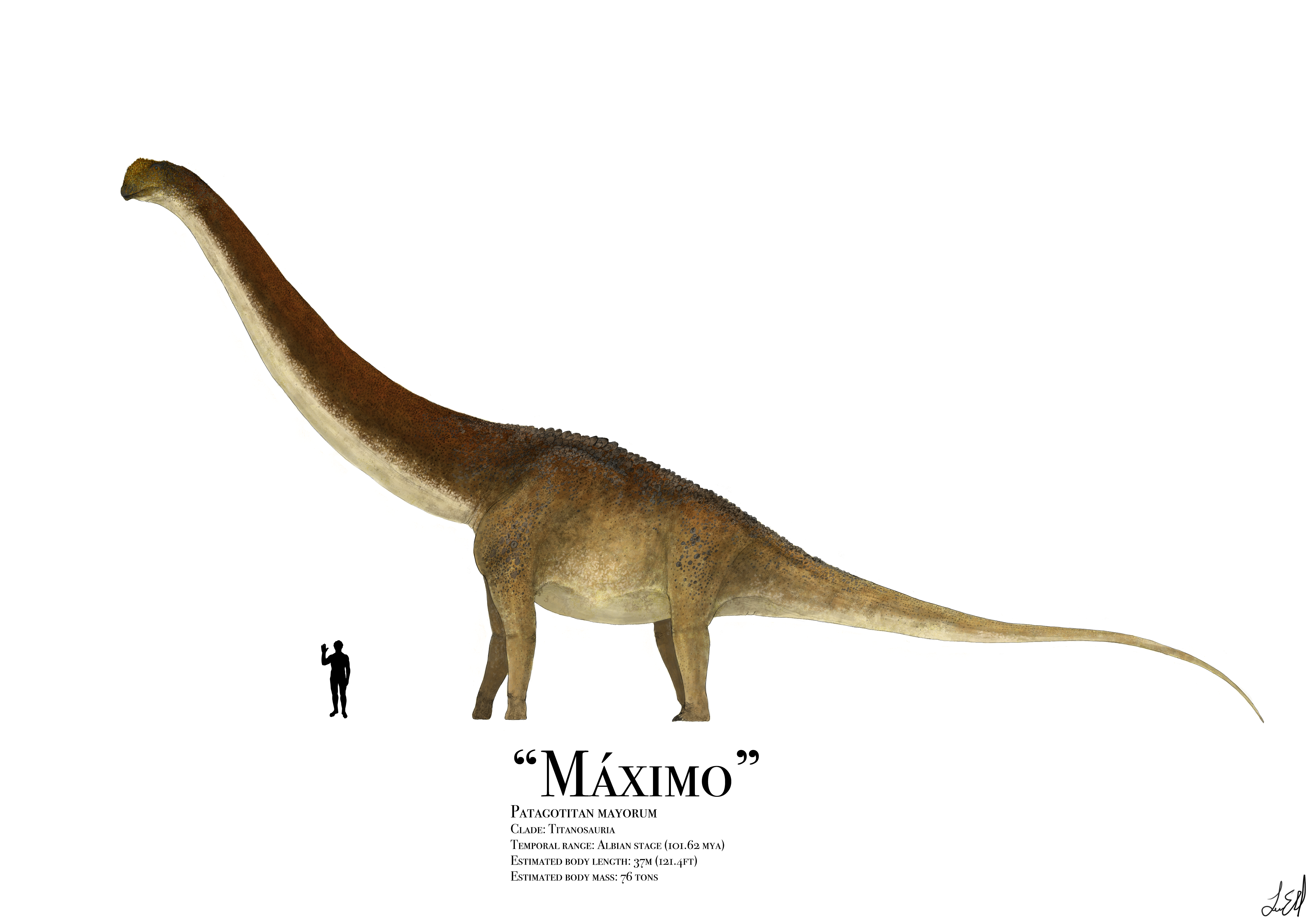

Above: Patagotitan, a giant titanosaur and one of the largest terrestrial animals ever (the other contenders are all other South American titanosaurs as well).

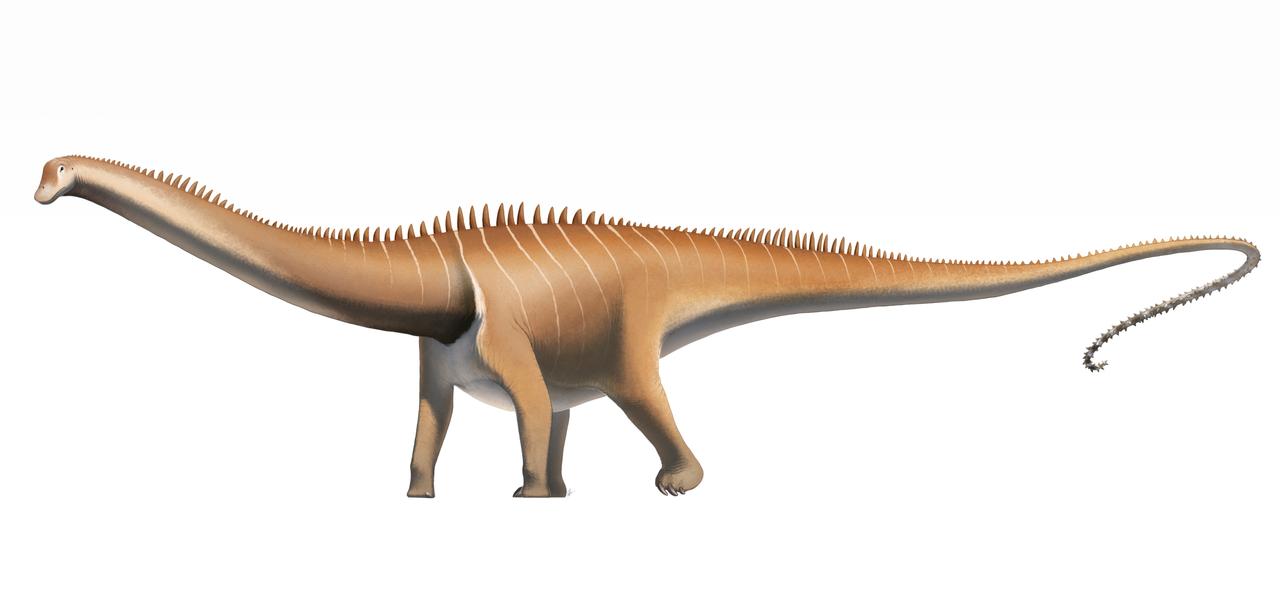

Above: Diplodocus, a classic well-known diplodocoid sauropod.

Here are some key features to note about sauropods:

- No toes! As sauropods got bigger, they had to develop special adaptations in their front legs to support their huge bulk. They lost basically all the digits in their front feet and walked on horseshoe-shaped “stumps” of bone. No toes would’ve been visible on the front feet at all, except the thumbclaw in diplodocoids, and even that one claw was lost in later titanosaurs.

- Consistent differences between titanosaurs and diplodocoids. You can read more about the two flavors of sauropods in my previous post on the dinosaur family, but I’ll quickly go over some of the main differences here. If it has a horizontal posture where the front legs are shorter or equal in length to the hind legs, it’s a diplodocoid, and should have a long, horselike face and a looooong whiplike tail. If it has a vertical posture where the front legs are significantly longer than the hind legs, it’s a titanosaur, and it should have a taller, deeper skull with a lot of soft tissue in the nasal / sinus area.

- Three visible toes in back. Straightforward, but for some reason media depictions often give them four or five. Why?

Pterosaurs

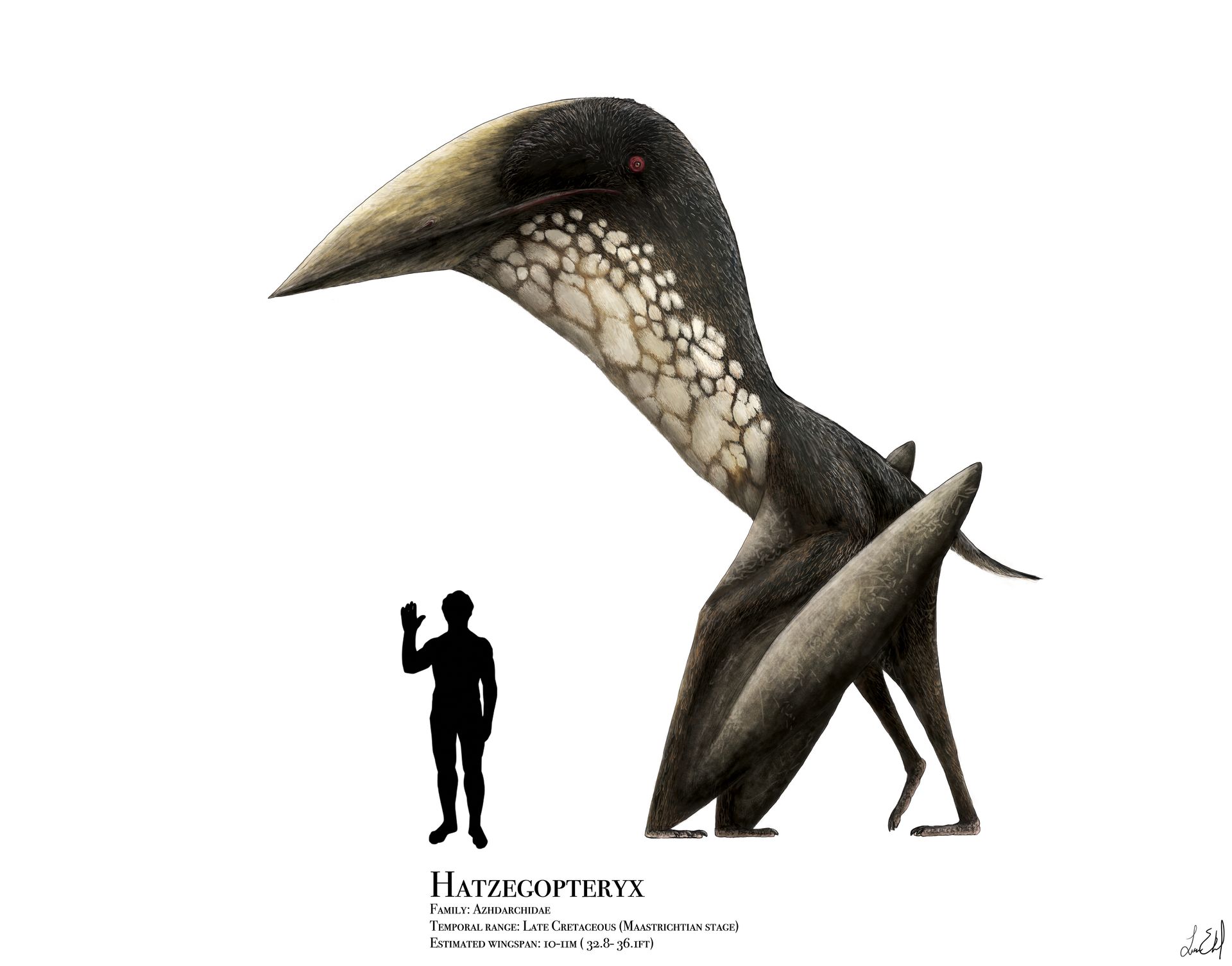

Above: Giant azhdarchid pterosaur Hatzegopteryx, one of the largest creatures ever to fly.

Above: Caviramus, a “rhamphorhynchoid” pterosaur from the Triassic (much more ancient than Late Cretaceous Hatzegopteryx).

Pterosaurs aren’t dinosaurs, but they’re close relatives and contemporaries, so they often show up side by side with dinosaurs in media. Here are some key features to note about pterosaurs:

- Quadrupedal stance and pole-vaulting takeoff. Pterosaurs had rather wimpy hind legs, and stood on all fours while on the ground. They would’ve taken off by launching over their front limbs like a pole-vaulter, rather than running bipedally while flapping like birds do. Check out this awesome video to see pterosaurs taking off.

- Plantigrade hind feet. Pterosaurs had feet superficially similar to our human feet–they walked on the whole foot, and were incapable of carrying things in their claws like a bird.

- Three joints before the wing fold. Unlike birds and bats, pterosaurs had an elongated wrist that is very noticeable while they’re on the ground.

- Enough membranes. In addition to the brachiopatagia, or main wing membranes, pterosaurs had propatagia, the membranes that stretch between the wrist and shoulder, and cruropatagia, the membranes that stretch between the hind leg and base of the tail (but do not include the tail). They were more wingy than people usually expect.

- Pycnofibres. Pterosaurs were covered in a fur-like integument called pycnofibres, which are related to feathers.

- Consistent differences between “rhamphorhynchoids” and pterodactyloids. Pterosaurs came in two main flavors, the toothy “rhamphorhynchoids” (in quotes because it’s a paraphyletic group) and the beaky pterodactyloids. “Rhamphorhynchoids” shared a variety of traits, including a long tail, teeth, and a sprawling grounded posture. Pterodactyloids had a short tail, a keratinous beak that usually didn’t have teeth, and an upright grounded posture. Media portrayals often show a mixture of these features on one animal.

Ornithischians

Above: Parasaurolophus, a famous hadrosaur (“duck-billed dinosaur”).

A couple key features to note about hadrosaurs:

- Quadrupedal stance. Hadrosaurs could probably rear up onto their hind legs, but usually walked on all fours. Older depictions show them with a kangaroo-like stance and a curved tail.

- Fat? Hadrosaurs had advanced chewing abilities, indicating that they were grazers rather than browsers. Tough grasses and other not-very-nutritious vegetation require a large and complex gut to digest (this is why cows have four stomachs), so hadrosaurs were probably pretty chunky-looking. Many older depictions show them as being more slender.

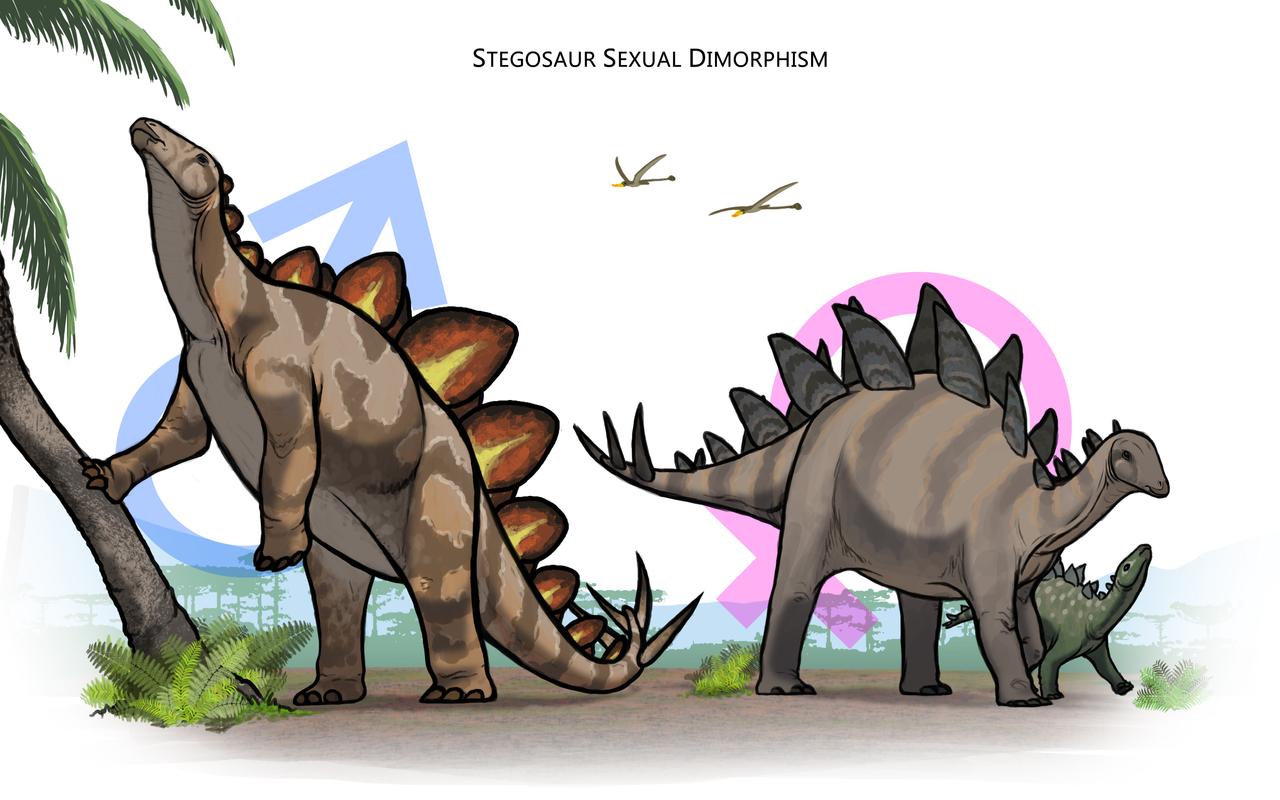

Above: Stegosaurus, the well-known Jurassic plate-backed dinosaur.

A couple key features to note about Stegosaurus:

- Alternating plates. The plates on Stegosaurus’s back weren’t paired like a mirror image, but were alternating like footprints. This isn’t the case for all stegosaurs, however.

- A particularly ancient dinosaur. Stegosaurus is one of the few Jurassic dinosaurs that’s really famous (most of the famous ones are from the Cretaceous, tens of millions of years later). Tyrannosaurus was closer in time to an iPhone than it was to Stegosaurus, so depictions showing the two side-by-side are very wrong. Stegosaurus lived alongside Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and possibly Liopleurodon and Pterodactylus. Tyrannosaurus lived alongside Triceratops, Pachycephalosaurus, Ankylosaurus, Edmontosaurus, Quetzalcoatlus, and Mosasaurus. These two groups of animals lived about 89 million years apart from each other.

I hope this post helps give you an idea of some basic things to look for in a media portrayal of dinosaurs and friends. Now you’re a licensed nitpicker. Congratulations!

Image credits:

Tyrannosaurus Utahraptor Patagotitan Diplodocus Caviramus Hatzegopteryx Parasaurolophus Stegosaurus