As a followup to my Dinosaur Family Overview post, here’s a similar pterosaur’s-eye view of the lineage of those awesome flying reptiles! This should be a significantly shorter post; since pterosaurs weren’t nearly as diverse as dinosaurs, there are fewer groups to cover.

Pterosauria

Pterosaurs (meaning “wing reptile”) aren’t dinosaurs, but they’re the next closest thing–Pterosauria is the sister clade to Dinosauromorpha. They’re the first group of vertebrates to unlock the achievement “Powered Flight” (insects did it first). They’re exceedingly specialized for flight, with delicate skeletons that don’t fossilize easily, so we don’t know much about how they transitioned into the air. As far as we’ve found, they suddenly appear in the fossil record of the Late Triassic, fully-formed and ready to fly. (This is coincidentally similar to their reproductive strategy, in which baby pterosaurs, called flaplings, are able to fly very shortly after birth.)

There are a few theories about how they developed flight–ground-up, arboreal leaping, and arboreal parachuting–but none of them really stick out as particularly better than the others. One animal often cited as a pterosaur ancestor is Scleromochlus, a tiny kangaroo-like archosaur that lived in the early Late Triassic (237-ish million years ago) and probably hopped adorably through the desert. Below is an image showing the speculative transitional forms between Scleromochlus and Preondactylus, an early pterosaur that lived in the middle Late Triassic (228-ish million years ago):

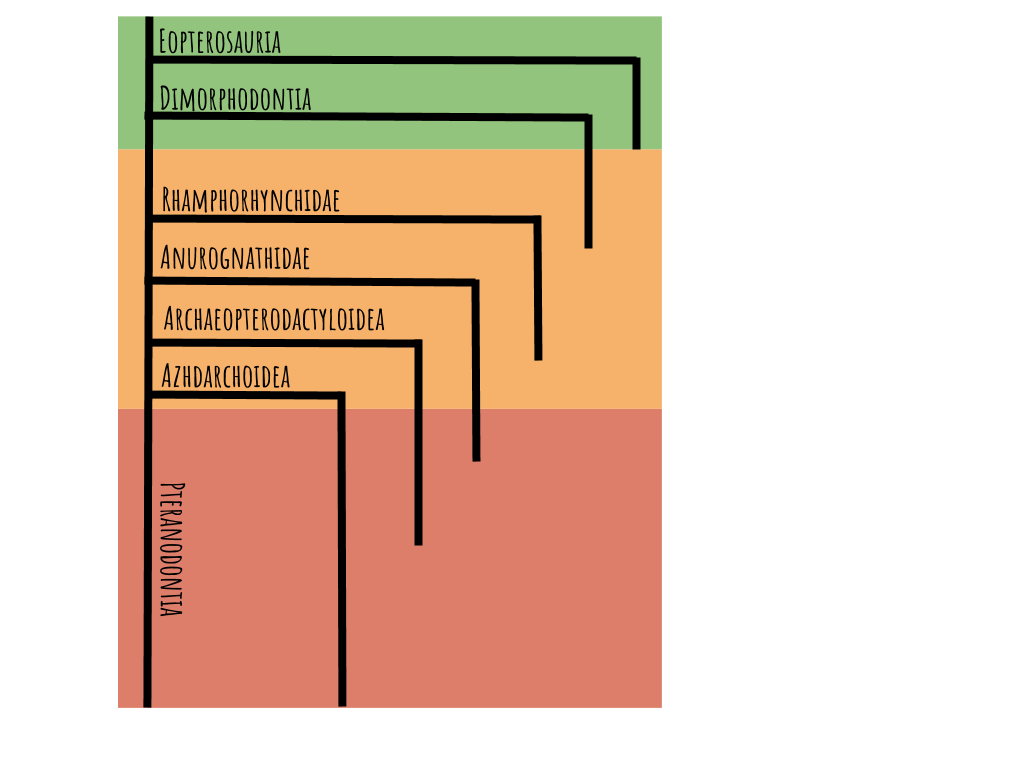

Once they could fly, pterosaurs quickly diversified into a variety of shapes and sizes. They can be separated into two main flavors: the “rhamphorhynchoids” (meaning “beak snout”) and the pterodactyloids (meaning “wing finger”). Here’s the tree:

Above: A simplified pterosaur family tree, approximately to scale. The green band represents the Triassic (we begin in the late Triassic here), the orange is Jurassic and the red is Cretaceous. When a line ends, it means that group has gone extinct. Note that this is not a comprehensive list of families; there are many genera that don’t fall into any of these groups.

The first four groups–Eopterosauria, Dimorphodontia, Rhamphorhynchidae, and Anurognathidae–together make up the “rhamphorhynchoids,” while the last three–Archaeopterodactyloidea, Azhdarchoidea, and Pteranodontia–make up the pterodactyloids. “Rhamphorhynchoids” is in quotes because it’s a paraphyletic group. You can see why based on this tree: any clade containing Eopterosauria and Dimorphodontia, for example, must also contain Azhdarchoidea and Pteranodontia (more on this in my other post, about why I am a fish. Effectively, calling something a “rhamphorhynchoid” is just saying it’s a pterosaur that’s not a pterodactyloid (and indeed, sometimes scientists refer to this group as the non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs).

Rhamphorhynchoidea

Even though it’s a paraphyletic group, “rhamphorhynchoids” do have a lot of features in common. They have toothy jaws or beaks that contain teeth, long tails, a sprawling quadrupedal stance, and they tend to be relatively small, with wingspans of usually 8 feet or less. They also tended not to have the extravagant head crests favored by many pterodactyloids, though some did sport some extreme headgear before it was cool.

Eopterosauria

Meaning “dawn wing reptile,” Eopterosauria includes the most ancient pterosaurs we know of. Some famous members include Caviramus, Preondactylus, and Eudimorphodon.

Above: Caviramus, an early pterosaur with an unusual large head crest. This picture makes it look kind of large, but it actually had a wingspan of only 4.5 feet (1.5m), comparable to a red-tailed hawk. Its wing shape suggests that it may have been adapted for soaring, and its teeth indicate that it may have been an herbivore or generalist.

Further reading: Caviramus details

Dimorphodontia

Meaning “two form tooth,” dimorphodontids look kind of like someone popped a theropod’s head onto a pterosaur’s body. Famous examples include Dimorphodon (of Jurassic World fame) and Caelestiventus, described in 2018 (pictured below).

Above: Caelestiventus, an early dimorphodontid pterosaur from the Late Triassic, 208 Ma, described in 2018. It had a 5-foot wingspan and lived in the desert, unusual for “rhamphorhynchoids”. Note that this batlike upside-down pose is artistic license–pterosaurs had plantigrade feet not unlike our own, which would’ve been good for walking around on the ground but useless for grasping.

Further reading: Caelestiventus discovery

Rhamphorhynchidae

Rhamphorhynchids were well-known Jurassic pterosaurs with long, slender snouts with interlocking, bear-trap-like teeth that were good for catching fish. Fossilized gut contents and coprolites (fossilized dung) show that they did indeed eat fish and other sea creatures. Famous members include Scaphognathus, which may have had a keratinous head crest, and Rhamphorhynchus (below).

Above: Rhamphorhynchus, imagined with coloration reminiscent of a seabird.

Note the difference between the very similar-sounding words (in order of increasing narrowness): “rhamphorhynch-OIDS” are the whole paraphyletic group of toothy, small, long-tailed pterosaurs; rhamphorhynch-IDS are a clade of fish-eating pterosaurs that include Rhamphorhynch-US, a genus of pterosaur.

Anurognathidae

Anurognathids were the group of pterosaurs that I was most surprised to learn about for the first time. They’re tiny, they have short, frog-like faces and huge eyes, and were probably insectivorous and nocturnal. They were pterosaurs convergent with bats! They may even have had special fuzzy wing edges for silent flight, like owls.

Above: Anurognathus chasing a bug in Jurassic Germany.

Above: A group of Anurognathus in a speculative tree hole nest. We don’t know if they were social, but since bats are and the two groups are so convergent in other ways, it’s not a bad guess.

Pterodactyloidea

Up to this point, the pterosaurs we’ve looked at have been small and, even though their appearance is somewhat alien, the niches that they fill are familiar. Eopterosaurians soared and ate whatever they could find, like seagulls; dimorphodontids killed small stem-lizards and stem-mammals, like hawks; rhamphorhynchids dove for fish like cormorants; and anurognathids caught insects on the wing like bats. However, something would soon out-compete pterosaurs in these niches: birds. The advent of birds that could do everything pterosaurs could do, but better*, required pterosaurs to adapt to doing things that birds couldn’t do–get huge. Birds are limited in size by their heavy, muscular legs, which need to be strong enough to launch them into the air for takeoff. At larger sizes, these can become prohibitively heavy (since the strength of a muscle depends on its cross-sectional area while its weight depends on its volume, the square-cube law applies. That’s why insects are so proportionally strong!). Pterosaurs, which took off by pole-vaulting over their front arms, were able to reduce their legs into skinny little twigs to save weight. In many giant pterosaurs, their thighbones were skinnier than their finger bones! This made a huge difference in maximum size–the largest flying bird ever, Pelagornis, had a wingspan of up to 24 feet and weighed up to 88 pounds, while the largest flying pterosaur ever, Quetzalcoatlus, had a wingspan of up to 36 feet and weighed up to 550 pounds!

Unfortunately, the pterosaurs’ strategy of going big or going home ended with them, well, going home. In times of scarcity, such as the nuclear winter following the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs, the largest animals tend to die out first, since they require more resources to stay alive. Birds, being small, suffered but bounced back; pterosaurs were not so lucky. Since then, though, no other animals have been able to fill that niche, leaving pterosaurs’ records as the largest creatures ever to fly unchallenged.

Pterodactyloids shared more features than just size–they tended to lack teeth, have short tails and elongated hand-bones, and many had extravagant head crests.

* There are a few theories on why birds had a competitive advantage over pterosaurs. One is their nesting habits: birds, with their hard-shelled eggs and dextrous feet, can build nests anywhere and out of anything, while pterosaurs likely buried their eggs like modern turtles and alligators, limiting them to nesting sites with appropriate dirt or sand. The egg-burying habit also forced pterosaur flaplings to be precocial, since they had to fend for themselves shortly after birth, while birds could afford to be altricial, which requires the parent to spend an extended amount of time caring for the helpless young. Being altricial allows more time for learning and development, which leads to a more diverse skill set as an adult.

Archaeopterodactyloidea

This group contains the famous Pterodactylus (there’s no such thing as a creature named “Pterodactyl,” by the way), which is much smaller than you imagine–about crow-sized. It also contains the much more exciting group Ctenochasmatidae, the comb-toothed filter-feeding pterosaurs, which filled the same niche as modern flamingos and spoonbills, eating small crustaceans and being fabulously pink. Recent coprolite evidence corroborates this theory.

Above: Pterodactylus landing on a log in Late Jurassic Germany. It was unremarkable as pterosaurs go, owing its disproportionate fame to the fact that it was the first pterosaur discovered and identified as a flying reptile, in the very early 1800s.

Above: Pterodaustro, the Cretaceous flamingo (or, flamingos are the Holocene Pterodaustro). It used its baleen-like teeth to strain water for small crustaceans. This diet would’ve made it pink. Its large feet may have been webbed for swimming.

Azhdarchoidea

This is the group containing the very largest pterosaurs, and also the ones with the most fantastic headgear. They were likely terrestrial stalkers, hunting small prey like dinosaur hatchlings on all fours on the ground. Famous examples include Quetzalcoatlus, Tapejara, Hatzegopteryx, and Azhdarcho.

Above: Tupandactylus, an Early Cretaceous tapejarid from Brazil. Some paleontologists speculate that it may have used its head crest like a rudder to steer while flying, but others say it was purely for display. A new study indicates that the crest might actually have been blue.

Above: Quetzalcoatlus, the largest creature ever to fly. It was taller than a giraffe (though less than a quarter of the weight).

Pteranodontia

We’ve reached the end! The last group of pterosaurs we’ll cover, Pteranodontia, means “winged toothless,” since these very derived pterosaurs had long, toothless beaks. Famous examples include Pteranodon, which had a tasteful handle-like pointy head crest, and Nyctosaurus, which had a flamboyant fork-like head crest that was taller than the rest of its body.

Above: Three Pteranodon flying over Late Cretaceous North America. The one in the middle with the short crest is a female. Over 1200 specimens of Pteranodon have been found, making it one of the best-understood pterosaurs.

Above: Nyctosaurus, with a speculative membranous crest. The one on the bottom left is reconstructed with a more conservative crest. With a crest like that, you’d better be colorful–no point in lugging that thing around and sacrificing any chance at stealth if you’re not going to go the whole nine yards!

That about wraps up our overview of the various types of pterosaurs. They’re definitely one of the coolest groups of Mesozoic animals, especially because in many cases, nothing remotely like them exists anymore. I hope all these crazy extinct creatures piqued your interest!

Image credits: Pterosaur Evolution Caviramus Caelestiventus Rhamphorhynchus Anurognathus Anurognathus Roost Pterodactylus Pterodaustro Tupandactylus Quetzalcoatlus Pteranodon Nyctosaurus