It’s that time of year again! I’m really excited to compare my efforts this year to last year’s, and see if/how I’ve improved. Here’s this year’s prompt list:

Last year I challenged myself to relate each prompt word to a Mesozoic reptile. This year I’ll do the same, but with the additional challenge of only drawing 2020 novataxa–that is, Mesozoic reptile genera named this year. Don’t worry, there are lots to choose from!

Day 1: Fish

It’s the new istiodactylid pterosaur, Luchibang, canopy feeding for the abundant fish Lycoptera, in Early Cretaceous China. Black herons do this weird thing where they make their wings into an umbrella shape to cast shade on the water while hunting for fish. Luchibang means “heron wing,” so I thought I’d have mine doing the same thing. According to Wikipedia, the shadow attracts fish, but it seems to me that it’s more likely that by holding the shade still for long enough, fish disperse back to the shaded area, thinking the shadow is cast by a tree or something. Then, when the predator’s head strikes, it doesn’t cast a new shadow that would alarm the fish. Since pterosaurs are quadrupedal, Luchibang isn’t quite as effective as a heron at making an umbrella shape.

The holotype of Luchibang was found with one Lycoptera between its jaws and two more in its stomach, so it probably did hunt these common little fish.

Day 2: Wisp

Overoraptor was a maniraptoran dinosaur from Late Cretaceous Argentina that shows a novel mix of traits found in dromaeosaurs (“raptor” dinosaurs) and birds. It had long, flight-adapted arms like a bird, but also long, running-adapted, sickle-clawed legs, like a dromaeosaur. Its name means “piebald thief,” because the holotype bones looked piebald. However, lots of modern birds exhibit alternative colorings (melanism, albinism, leucism, and piebaldism), so I made my Overoraptor actually piebald on the outside. The pose and feathering are inspired by the photo I took of a greylag goose that had just finished preening itself, and had wisps of downy feathers stuck to its beak. Check out last week’s post to see that photo and more. Modern birds spend tons of time preening themselves, so I’d expect at least the more birdlike of the non-avian dinosaurs to have engaged in similar behavior.

Day 3: Bulky

Here’s Yamanasaurus and Analong, two newly discovered sauropods, showing off their different gaits. Yamanasaurus was a saltasaurine titanosaur from Late Cretaceous Ecuador, and Analong was a mamenchisaurid from Middle Jurassic China.

There are two types of sauropod trackways (footprint fossils): wide-gauge and narrow-gauge. They both come in very large and not-so-large sizes, indicating that the difference is due to lineage rather than animal size. Wide-gauge trackways, like Titanopodus shown here, had the prints far from the animal’s midline and the manus and pes (hand and foot) prints far from each other. This type of trackway would’ve been produced by titanosaurs, the family that includes the largest animals ever to walk. To imagine how they walked, do a “bear walk”–move on all fours with your arms and legs mostly straight. Narrow-gauge trackways, like Brontopodus shown here, had the prints close to or even overlapping the midline, and the manus and pes prints close together. This type would have been produced by all non-titanosaurian sauropods, including diplodocoids, mamenchisaurids, and others. To imagine this, watch a cat walk and imagine it’s the size of a house.

While the narrow-gauged gait looks more graceful and energy-efficient, it seems to be size-limited. That is, to reach the largest sizes, sauropods were forced to adopt the wide-gauge walk. Then, once the titanosaur family had committed to this body plan, some of them reduced in size again, but kept the wide-stepping habit.

I wanted to draw some sauropods from front view because nobody ever does that. It’s as if dinosaurs only have one side. Also, note that these specific dinosaurs were not the ones who made these specific trackways; rather, both are just examples of the wide and narrow habits.

Day 4: Radio

I was having a hard time figuring out how I was going to relate “radio” to Mesozoic reptiles, and then it hit me–radiometric dating! Before drawing this comic, I knew vaguely how it worked, but the research I did to create this gave me a much deeper understanding. The characters shown here are ones I’m thinking about using in a couple of paleontology children’s books. So far, the rapport could use some work–it’s mostly just Paige explaining for days. Man, this took forever. I don’t know how real comic artists do it.

The novataxon that makes a guest appearance in the strip is Kholumolumo, a sauropodomorph (early relative of the long-necks) from Late Triassic Lesotho.

I’m weirdly proud of the panel where she’s doing the “bracketing” gesture.

Day 5: Blade

This is Adratiklit, a stegosaur from Middle Jurassic Morocco. It’s only known from fragmentary material–enough to place it in a family with Dacentrurus and Miragaia (and extrapolate that it probably looked similar to them), but not enough to really say anything about Adratiklit itself. To be honest, I think stegosaurs are highly overrated dinosaurs. They didn’t have much diversity of forms, and went extinct halfway through the Age of Dinosaurs, at the end of the Jurassic.

Because the prompt was “blade,” I went for another front view, to show the blade-like thin sharp plates. Stegosaur front-views are also ridiculously uncommon, though thankfully there are couple skeletal top-views I could reference. Next time I go to a natural history museum, I’m going to take photos of all the mounted skeletons from all the views I can.

I was trying to give Adratiklit a smooth combination of large-animal features and bird features, which is why he has a wattle. I’m not super happy with how comically small the spikes ended up looking against his giant body though.

Day 6: Rodent

Okay, this picture doesn’t actually feature any rodents, but since rodents didn’t arise until the non-avian dinosaurs were extinct, I took some artistic license. This is the new mini carcharodontosaur, Lajasvenator, chasing the long-tailed cladotherian mammal (early relative of marsupials and placentals) Vincelestes in Early Cretaceous Argentina. Carcharodontosaurs were a group of generally very large carnivorous theropods with shark-like slicing teeth. The largest members, Carcharodontosaurus, Giganotosaurus, and Mapusaurus, rivaled Tyrannosaurus in size. Lajasvenator, on the other hand, was merely the size of a big dog.

I wanted to depict this miniaturized carcharodontosaur for the prompt “rodent” because unlike its larger relatives, a rodent-like mammal would have been one of its preferred prey items. Usually, rodent-like mammals are depicted being preyed upon by dromaeosaurs and compsognathids–families of theropods whose members are normally small. It’s more fun to show an unusual rodent-chaser.

I gave my Lajasvenator an iguana-like keratin structure on its head because many carcharodontosaurs show evidence of some kind of horn structure there, but it’s unclear whether it was exposed keratin like an antler, covered with skin, or covered with something else. In the past I always went the antler route, but I wanted to try something new this time.

Day 7: Fancy

Here’s Kompsornis, a long-tailed jeholornithiform bird from Early Cretaceous China. Its name means “elegant bird,” which is why I chose it for this prompt. The plumage is based on an ornate hawk-eagle, which I found by googling “fancy bird”. Most birds whose plumage is considered fancy sport impressive colors, which doesn’t go so well with Inktober. The ornate hawk-eagle, though, has cool patterns that worked well with my black and sepia pens.

Continuing my trend of dinosaurs from front view this year. There’s definitely also a paucity of maniraptor front views.

Often, when paleontologists see an animal from a toothed lineage develop a toothless beak, they point to it as a transition to herbivory. However, lots of modern birds are hyper-carnivores, insectivores, and opportunistic omnivores. Is this because they had already developed the beak for herbivory, and then switched back to carnivory? Or does it mean that beak != herbivore in the first place?

Day 8: Teeth

Teeth are something dinosaurs are quite good at. Here is a comparison of tooth types among the three main groups of large carnivorous theropods: abelisaurs, carcharodontosaurs, and tyrannosaurs. They all hunted a little bit differently!

The novataxa depicted are Tralkasaurus, from Late Cretaceous Argentina; Lusovenator, from Late Jurassic Portugal; and Jinbeisaurus, from Late Cretaceous China. All are medium-smallish representatives of their respective groups.

Abelisaurs, the group that includes the famous Carnotaurus, had really short faces, stout teeth, and powerful neck muscles. These adaptations were good for resisting torsion, indicating they would’ve taken down their prey sort of like a big cat–biting the face or throat and holding on until the prey was subdued. Carcharodontosaurs (technically meaning “sharp-toothed reptile” but named after the shark genera Carcharias and Carcharocles) had shark-like, thin, serrated teeth, good for slicing, and long, deep skulls that would have been good at resisting compression. It’s not totally agreed upon how they hunted–suggestions include biting the legs over and over like a wolf, using the head like an axe, and flesh-grazing (tearing out a chunk and scooting off, leaving the prey injured but alive)–but their teeth would definitely have been good for some mode of flesh-tearing. Tyrannosaurs had banana-shaped teeth that would have been strong in all directions, and the jaw musculature to enable them to crush bone. This, along with their heightened senses and bigger brains compared to the carcharodontosaurs, helped them usurp the apex predator position toward the end of the Age of Reptiles.

I think tyrannosaurs are just so handsome compared to the other two groups shown here. They have a very distinctive face shape. I think it’s that aquiline nose (as opposed to carcharodontosaurs’ Roman nose) and the strong jawline.

I guess another group I could have included is the spinosaurids, who had needle-like teeth for a fish-catching bite. The only spinosaurid novataxon from this year is Vallibonavenatrix though, and I’m saving her for a different prompt. Plus, even three dino portraits were pretty crowded on this little paper.

Day 9: Throw

Here are some Wightia, a new tapejarid pterosaur from the Isle of Wight, throwing themselves off cliffs. I wanted to experiment with a bit more pterosaur posture diversity. The ones with the tall crests are males; the ones with the rounded crests are females. Unlike how I drew Luchibang on Day 1, the last phalanx in Wightia’s flight finger is crooked relative to the rest, creating a more round-ended wing profile. I’m not sure how flexible the overgrown wing finger was and how much its range of motion could vary between pterosaur groups…if you know a good study, point me to it.

Day 10: Hope

A Huinculsaurus chick (one of the strange, beaked, herbivorous relatives of Carnotaurus known as noasaurs) sits on its mud nest and hopes its mother will return soon with food.

Okay, you may have noticed that what I’m calling a noasaur is just an albatross chick. Keen observation. I was inspired by how silly the enormous, helpless albatross chicks look while waiting on their nests. It makes a striking composition. Probably most dinosaurs were not this altricial (helpless at birth and requiring extensive parental care), but perhaps some were. And while adult albatrosses and adult Huinculsaurus would have looked quite different from one another, the chicks are so fluffy that you can’t even tell what is going on under the fuzz.

Foliage is quite labor-intensive to draw. I’m surprisingly happy with how it turned out though.

Day 11: Disgusting

Two Trierarchuncus, the Hell Creek alvarezsaur, pick grubs out of a hadrosaur patty. Alvarezsaurs were a weird group of purportedly insectivorous maniraptorans that had just one big finger per hand that they may have used to rip open rotting wood to reach termites and grubs living inside. Triearchuncus means “Captain Hook,” in reference to this little dinosaur’s overgrown claws. (Scientists love to give dinosaurs encoded silly names. No one would name their new dinosaur “Captainhookosaurus,” but translate it into Greek and Latin and it becomes kosher.)

Picking at dry cow patties to eat the maggots inside is a favorite pastime of the modern chicken. They help to keep the insect population in control and spread the nutritious patty material across the ground. Their own nitrogen-rich droppings also help new ground cover to grow, which the cows then can eat, keeping the cycle going. Mutualistic relationships like this are common among all well-developed ecosystems, so it’s reasonable to guess that non-avian dinosaurs may have engaged in similar behavior. The coat pattern is inspired by a modern insectivore, the numbat.

Day 12: Slippery

Narindasaurus takes a bad spill while crossing a creek. He didn’t realize the rocks were so mossy.

Narindasaurus was a turiasaur (primitive, unspecialized sauropod) from Middle Jurassic Madagascar. I’ve already drawn a titanosaur and a mamenchisaur on Day 3, so I wanted to do a different breed for this one.

You think you, with your puny seven neck vertebrae, get bad whiplash after a fall or car accident? I wonder if a sauropod would survive this kind of fall even if it didn’t hit its head on a rock. Maybe they had some kind of neck adaptation to mitigate this. Or maybe their heads were just so small and light that the whip action wasn’t as powerful. Or maybe they just rarely fell down.

Day 13: Dune

It’s Beg tse, the little basal ceratopsian from Early Cretaceous Mongolia. The ancestors of Triceratops and kin were small and bipedal, and had minimal neck frills. Beg is named after a Mongolian war deity and has the second-shortest binomial name of all non-avian dinosaurs (the first being the famous Yi qi, and closely followed by a third-place Mei long). First top view of the series, and only the second ornithischian! #saurischianprivilege

Day 14: Armor

Here’s Navajoceratops, a newly discovered transitional ceratopsian from Late Cretaceous North America. This, along with Terminocavus, another ceratopsian named in the same paper, represent newly discovered transitional forms between Pentaceratops and Anchiceratops.

While the horns of ceratopsians may have been useful as weapons or at least deterrants, the frills were often paper-thin and would not have been good for armor, only for display. Instead, I gave my Navajoceratops some rear-facing armor in the form of porcupine-like quills. This isn’t a new idea, and in fact I’ve argued against its likelihood before, but it sure does make a nice ink drawing!

I think detailed, repeated ink patterns like this are sort of like the art version of ultramarathon running. If you can’t win a regular marathon, you just run for longer; if you can’t make good lineart or gestures, you go for broke on detail. It takes hours but doesn’t really require much skill.

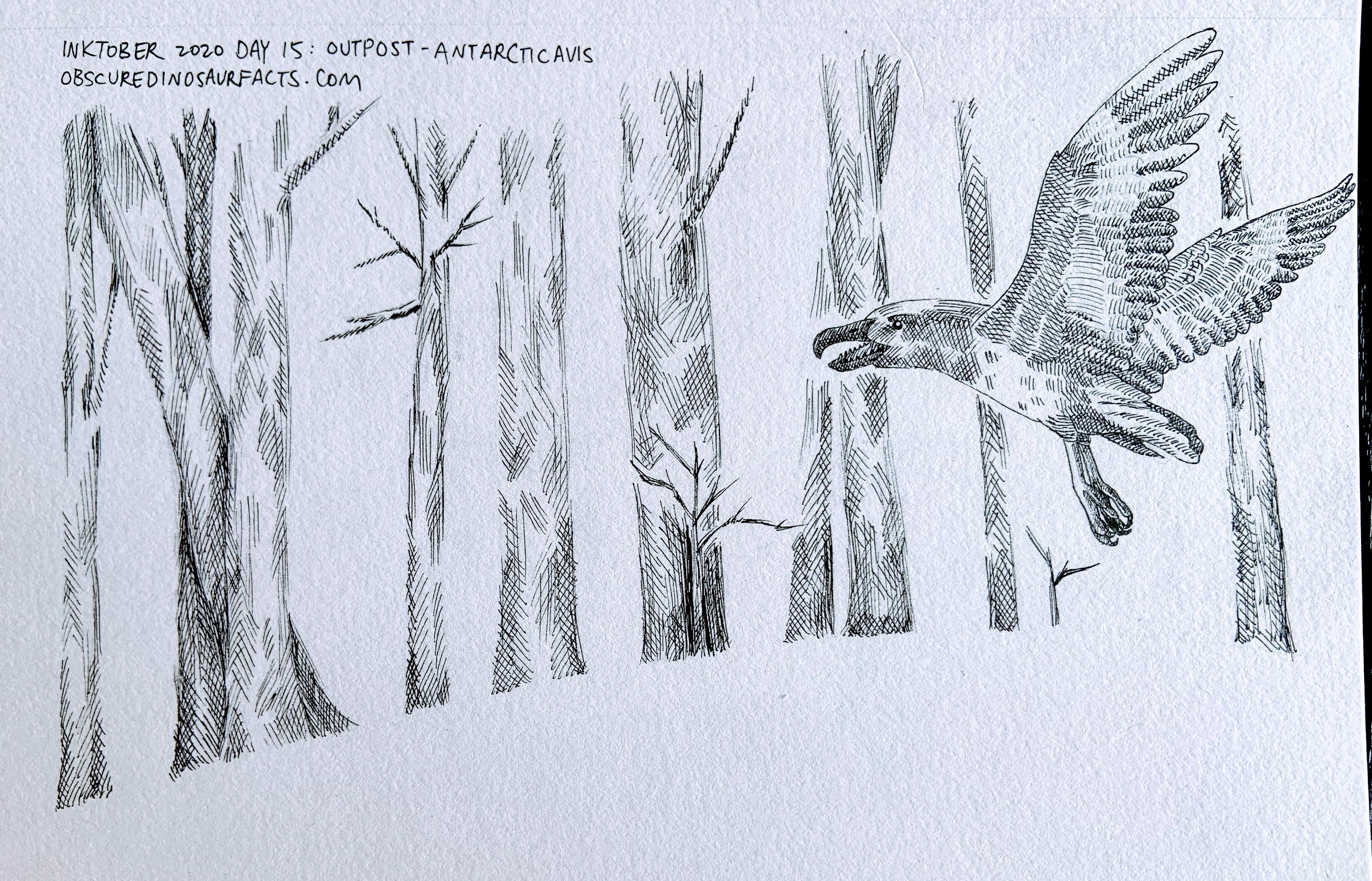

Day 15: Outpost

This is Antarcticavis, a bird we know very little about, from Late Cretaceous Antarctica. The fragmentary fossils are just informative enough that scientists can tell that it’s a bird that’s not Vegavis and not Polarornis, two other known birds from the same time and place, but that’s pretty much it. Here, I’ve reconstructed it as an ichthyornithine, a basal toothed bird. Ichthyornis is super common across Late Cretaceous North America, and is thought to have been seagull-like; however, no other birds are known from within that family. The skua is a gull that switched over to a more bird-of-prey type niche in modern Antarctica, so my Antarcticavis is an ichthyornithine that also moved to Antarctica and became more predatory. It represents a distant outpost of the ichthyornithine branch.

I just finished reading The Bird Way, by Jennifer Ackerman (she also wrote The Genius of Birds, which I’d read and enjoyed) and it features a lot of really nice ink drawings in a style different than my usual. I tried mimicking that style for this piece.

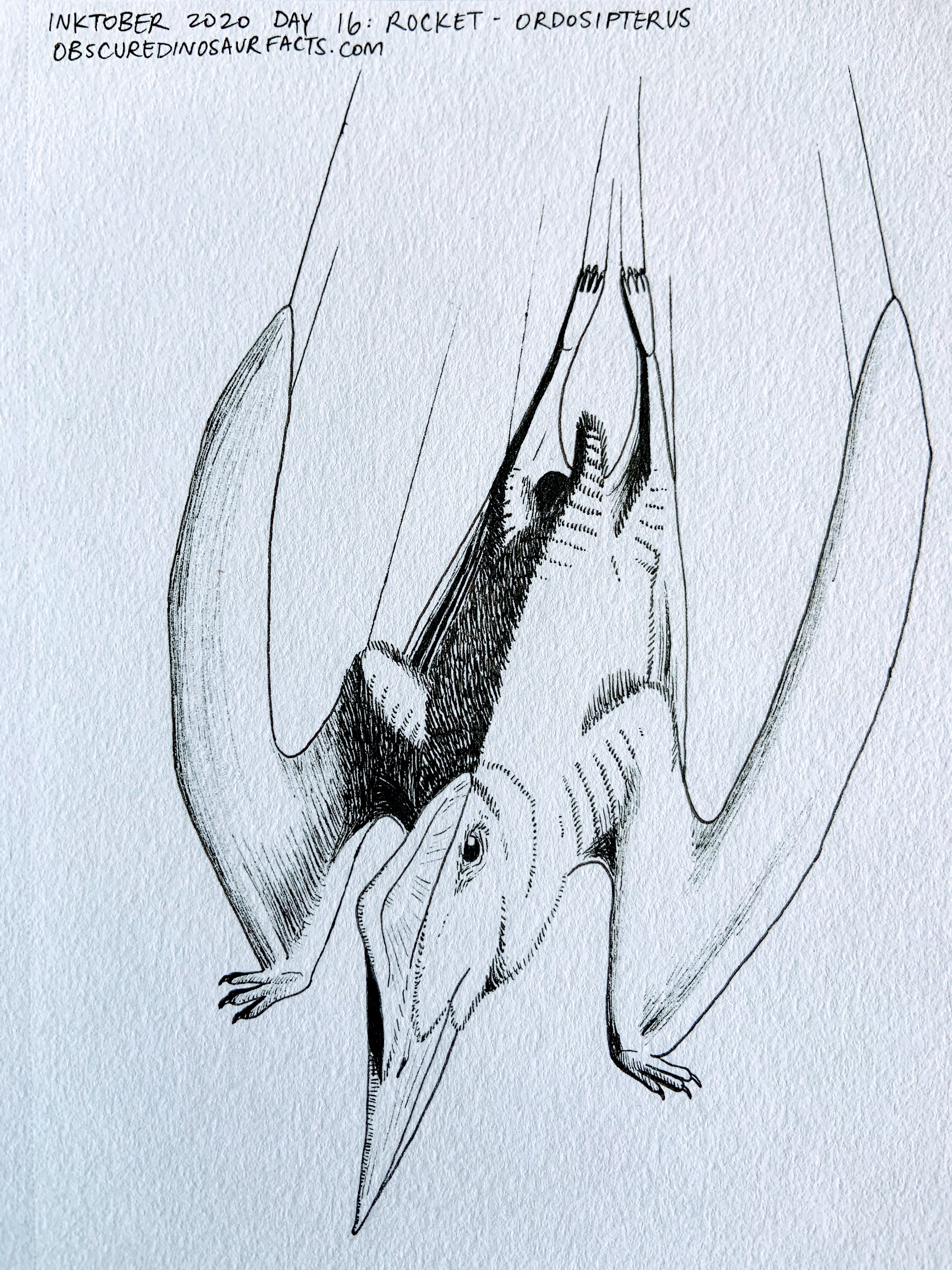

Day 16: Rocket

It’s Ordosipterus, a dsungaripterid pterosaur from Early Cretaceous China. While other dsungaripterids were probably durophages, using their upturned beaks to pry shellfish off rocks and their globular molars to crush the shells, Ordosipterus was probably not. It had a wider, less upturned beak with flatter molars, and was much smaller than the closely related Dsungaripterus. We don’t know what it was doing, but perhaps it was part of a lineage that diverged in function from the rest of the dsungaripterids. In this picture, it’s adopting a falcon-like “stoop” diving posture, maybe to rocket past a flying bird and whack its wing, causing it to crash. Less adapted for extreme speed than a modern falcon, Ordosipterus would not have needed to be to prey on Early Cretaceous birds, which were often poor fliers.

I wouldn’t say Ordosipterus would’ve been my top choice for a falcon-like pterosaur predator, but there have only been a handful of new pterosaur genera described this year, so I picked the best choice out of those.

In terms of style, I was trying to use comic-book-like dramatic shading and speed lines to make it look more rocket-like.

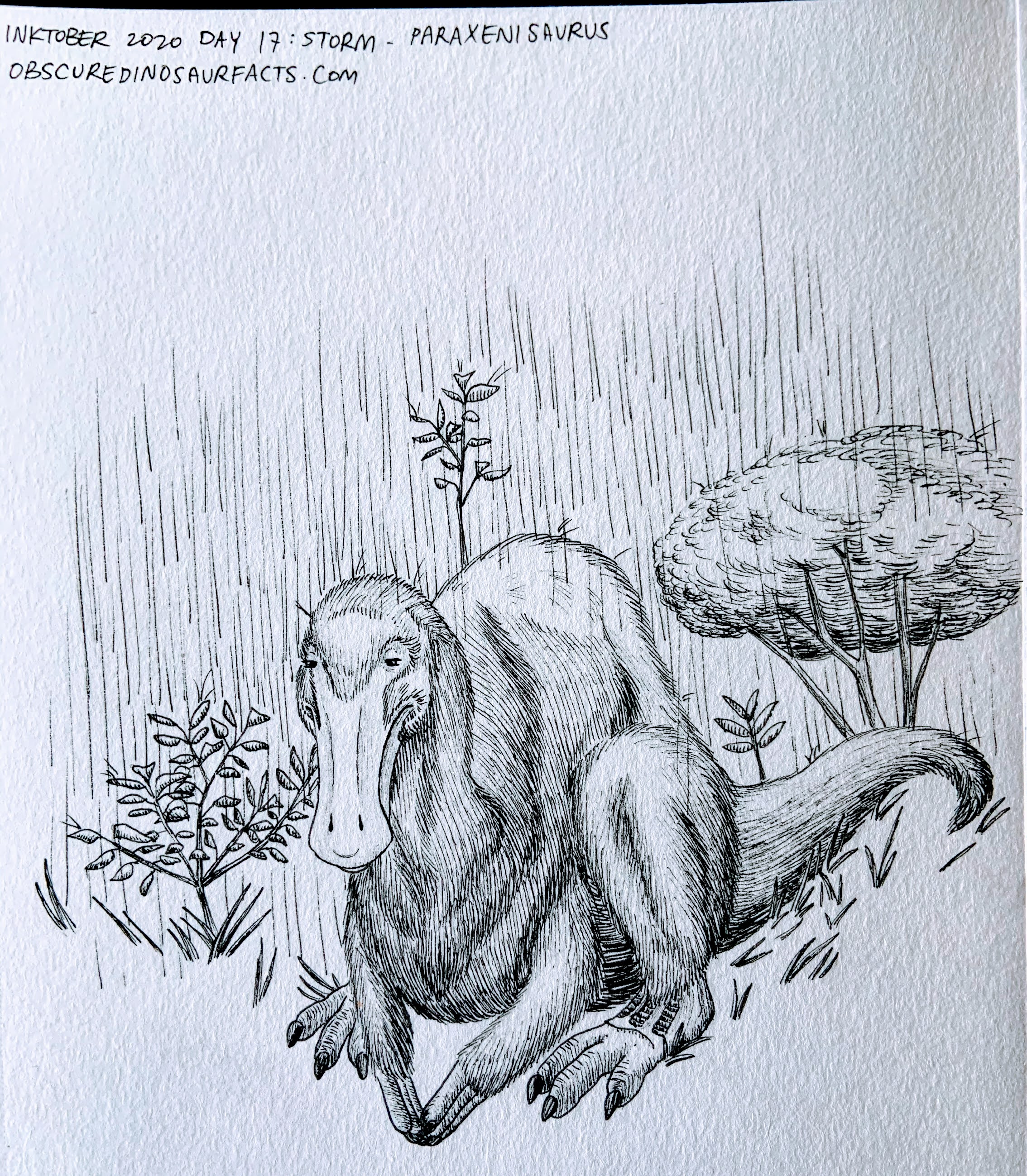

Day 17: Storm

*Sad deinocheirid noises*

Paraxenisaurus was a probable deinocheirid dinosaur from Late Cretaceous Mexico. The deinocheirids were an enigmatic group of duck-billed hump-backed giant ornithomimosaurs whose existence was known since 1965 but didn’t have all their puzzle piece body parts put together until 2014. While Deinocheirus was far too big at 6.4 tonnes to have had a heavy feather coat, Paraxenisaurus was only a tenth of that size, so I’ve given it a bearlike shaggy pelage.

Primitive feathers would not have been nearly as good as modern birds’ feathers at repelling water, so under stormy conditions certain dinosaurs would have gotten uncomfortably soaked. I’m quite proud of how Eeyore-esque he looks.

Day 18: Trap

Xunmenglong, a teeny-tiny compsognathid from Early Cretaceous China, gets caught in a death trap. The web owner will feast on this oversized prize for days!

Compsognathids were the dinosaur version of rats: small generalists that closely resemble the ancestral form.

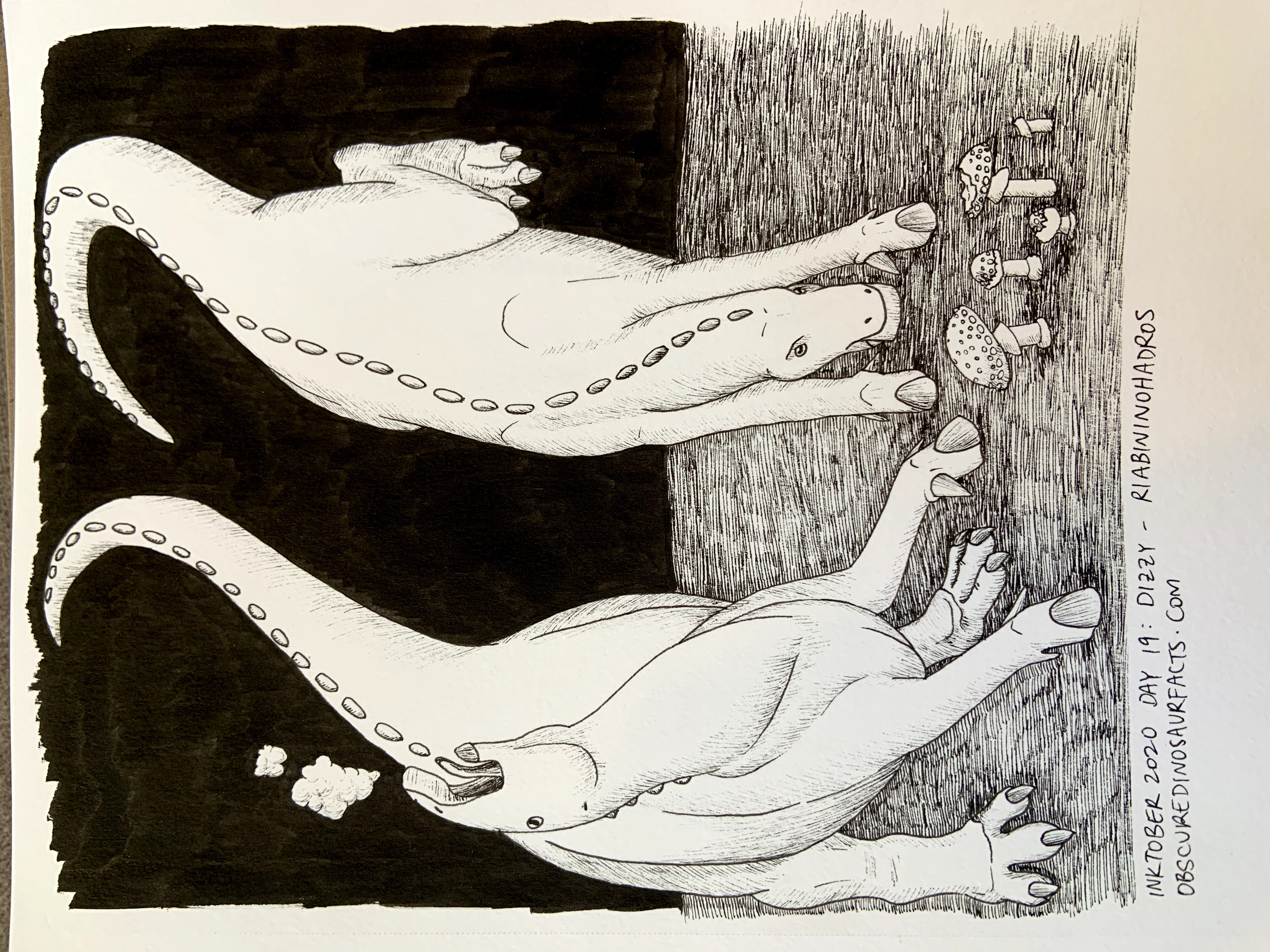

Day 19: Dizzy

Them dragon-horses be tripping!

A pair of Riabininohadros (an iguanodont from Late Cretaceous Ukraine) share some psychedelic mushrooms. Reindeer are known to purposefully consume the mind-altering Amanita muscaria and even fight each other over mushroom availability; this is just one example of drug use among animals. I wouldn’t be surprised if non-avian dinosaurs liked to feel good sometimes too.

Day 20: Coral

Vallibonavenatrix is a new genus of spinosaurid from Early Cretaceous Spain. With the new Spinosaurus swimmy tail discovered this year, we now know that these dinosaurs were even more convergent with crocs than previously thought. Giving Vallibonavenatrix a laterally compressed tail makes her look just like a long-legged saltwater crocodile.

I gave her a croc-style cloaca (a sagitally oriented slit) just because those were the only type I’d ever seen. Turns out birds have square or round cloacae, and lizards have medially oriented slits. However, brand-new research describes the first preserved non-avian dinosaur cloaca known to science, in the small basal ceratopsian Psittacosaurus. And guess what–it had a croc-style slit! I got lucky! That’s not to say theropods like Vallibonavenatrix would’ve necessarily had the same style of cloaca, but it’s at least plausible.

Day 21: Sleep

Here’s the new small basal ornithopod, Changmiania, from Early Cretaceous China. This dinosaur is known from two beautifully-preserved complete skeletons that were buried intact when their burrows collapsed. Further evidence for a fossorial lifestyle includes adaptations such as a shovel-like snout and extended shoulder blades for anchoring powerful arm muscles. The name means “eternal sleep,” since the skeletons were preserved in lifelike sleeping positions.

The “official” reconstruction of the holotype shows a fluffy, but somewhat skinny, dinosaur, whose anatomy is easily digestible by the viewer; I wanted to take a different approach. My Changmiania is a dinosaur equivalent to the golden mole, which is a bizarre, eyeless, iridescent, potatolike afrotherian from the deserts of southern Africa whose skeleton looks like that of a perfectly normal-shaped small mammal. Check out the inside view!

Day 22: Chef

“Chef” was a difficult one to relate to dinosaurs, since animals don’t do a lot of food preparation. The only things I could think of were burying food and digging it up later, like a dog, monkey, or corvid, and washing food like a raccoon. The latter is more of a chef-like behavior, since burying food is arguably just for the purpose of caching rather than food preparation. So here’s Dineobellator (meaning “Navajo warrior”), the new velociraptorine from Latest Cretaceous New Mexico, washing Meniscoessus, a multituberculate mammal.

A couple things were challenging about this piece. As an adaptation for grasping items without the primary feathers getting in the way, my Dineobellator has its primaries held more perpendicular to the hand rather than fanned forward. I also was having a hard time with the perspective–I meant for the gray part behind the white eyespots to be his neck, but it ended up looking more like a big domed cranium.

I guess drawing dinosaurs from front or back view is another theme this Inktober.

Day 23: Rip

Thank goodness for Gnathomortis! I was worried we weren’t going to see any new mosasaur genera this year, but this guy was named just in time for Inktober!

Mosasaurs were lizards, possibly relatives of monitors, possibly relatives of snakes, that made the transition to a fully aquatic lifestyle in the Late Cretaceous period. Like other marine reptiles, they would have been streamlined rather than scaly, warm-blooded, and given live birth tail first. Unlike other marine reptiles, they were still lizards, and therefore would have had forked tongues, “forked” penises, a pineal (third) eye on top of their head, and would have shed their skin. Imagine huge discarded mosasaur skins washing up on the beach! What a sight to see. [Update: I have learned that whales actually shed large portions of their skin at once, a strategy that helps prevent skin infection. The shed skin is almost immediately set upon by ocean scavengers and are rare to actually find. So perhaps mosasaur skins would have been similarly rapidly consumed.]

I was inspired by my fellow paleo Inktober participant, u/jupiter1390, who on Day 2 did a beautiful depiction of bioluminescent squid using white ink. I asked what kind of white pen they used, ordered them, and here we are. It’ll take some getting used to, but I’m happy with how this one turned out at least!

Day 24: Dig

This is Mirusavis, a small enantiornithine bird from Early Cretaceous China. Its holotype preserves a ridiculous amount of medullary bone, which is a type of bone formed temporarily in females as a calcium reserve for producing eggshells. Other dinosaurs and modern birds are known to have medullary bone deposits in their leg bones, but Mirusavis had it everywhere, including the ribs, vertebrae, and arm bones. This indicates that Mirusavis’s eggs would have been very large compared to its body size–estimated at 20%, comparable to the massive egg of the diminutive kiwi bird today. And a large egg indicates precociality, meaning Mirusavis chicks would have been born ready to run, fly, and feed themselves.

A modern example of a superprecocial bird is the Australian brush turkey. The male turkey builds a huge mound of dirt, sticks, and leaf litter that he meticulously guards and upkeeps. The female lays her eggs inside the mound, which, since it’s basically a big compost pile, provides heat to incubate the clutch of eggs. Once the chicks hatch, they must dig their way out from under a huge pile of dirt, like little bird zombies.

The weird thing is that the male turkey has no idea what his mound is for. He fastidiously checks the temperature inside the mound every day, and adds more compostables if it’s too cold, or digs out a vent in the middle if it’s too hot. But when the female digs a large hole in the mound to lay eggs in, he tries to chase her off and fill the hole immediately. When his chicks hatch, he tries to chase them off too, since to him they’re just some unknown actors messing with his beautiful mound.

Nature is very strange. Life finds a way.

Day 25: Buddy

Schleitheimia was a sauropodomorph closely related to the much better known Plateosaurus, from Late Triassic Switzerland. It’s known from only fragmentary remains, so I based my reconstruction mostly on Plateosaurus.

Modern crocodilians are known to team up with ground-nesting birds to share nest-guarding duties. The crocs can scare off large animals that threaten to trample the birds’ eggs, and the birds can chase away egg-breaking lizards and other small, nimble threats. Here, Schleitheimia forms a similar partnership with Procompsognathus, of Jurassic Park 2 fame. Procompsognathus is not related to true compsognathids, but rather is a very small coelophysoid. But since as I said on Day 18, compsognathids closely resemble dinosaurs’ ancestral form, it’s not really a surprise that older dinosaurs would have looked very similar.

Day 26: Hide

Dynamosuchus was a bobcat-sized ornithosuchid pseudosuchian from early Late Triassic Brazil. Ornithosuchids (meaning “bird croc” for some reason) were an early branch off the main croc tree that kind of pioneered the quadrupedal terrestrial predator strategy that would be further explored later by more famous pseudosuchians like Fasolasuchus, Postosuchus, and Saurosuchus. Only four other genera of ornithosuchid are known, so the description of Dynamosuchus increases their diversity by 25%!

I’ve given my Dynamosuchus cryptic coloring like a jaguar, for hiding amongst leaf litter. It’s just a lucky coincidence that I sort of incorporated the other meaning of “hide” into this piece–his hide is what’s colored. Someone on Reddit pointed this out.

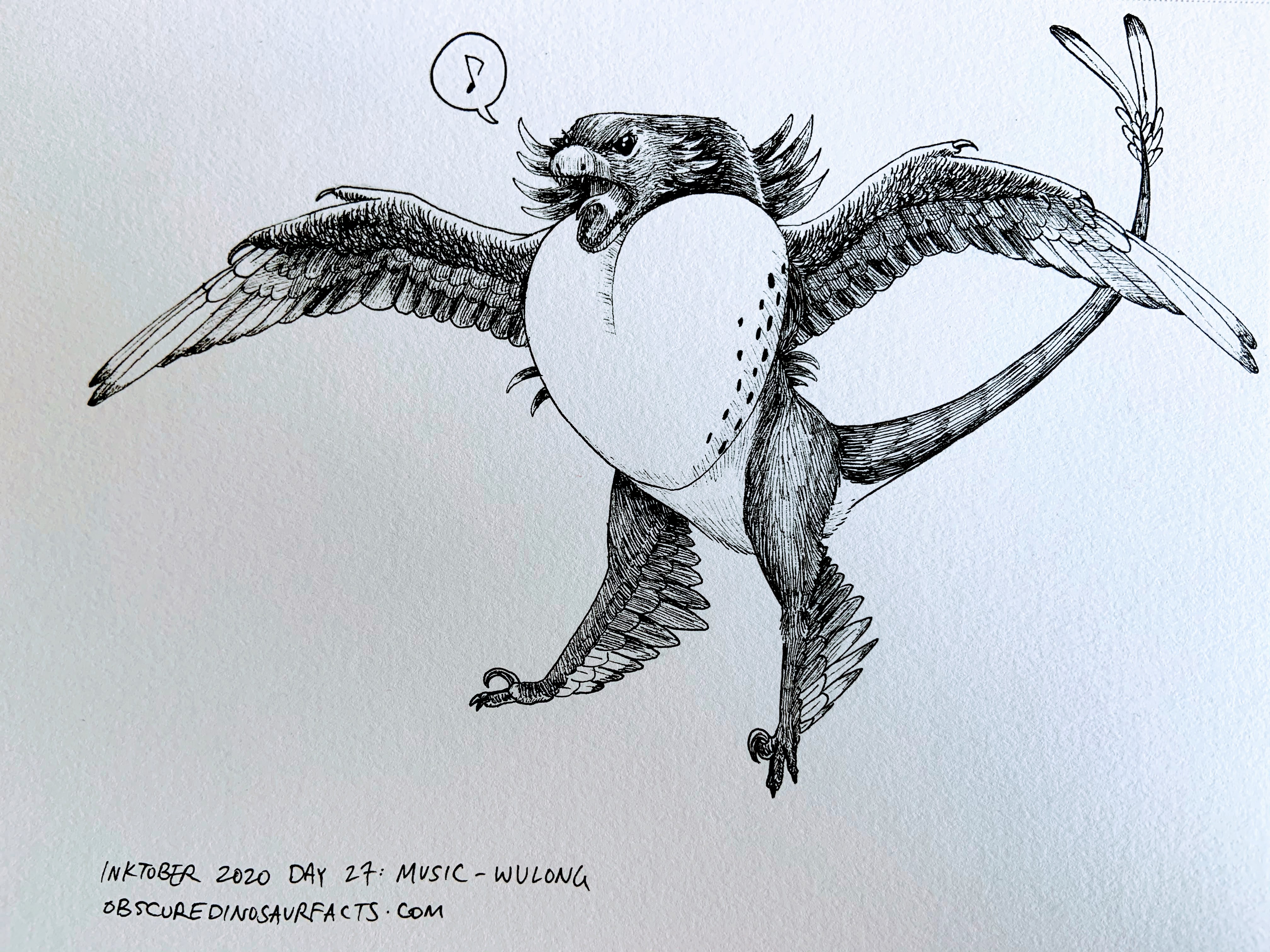

Day 27: Music

This is Wulong, meaning “dancing dragon,” a new microraptorine (four-winged “raptor” dinosaur) from Early Cretaceous China. This one is doing a mating song and dance akin to a frigatebird, inflating its colorful display pouch for the females to see.

Even though bird wings are pretty constrained by their function, there is still diversity in their shape, posture, and feathering. Usually I see microraptorines depicted with songbird-like rounded wings; this one has more angular wings. On a creature this size maybe that doesn’t make sense, but it looks kind of cool and unusual.

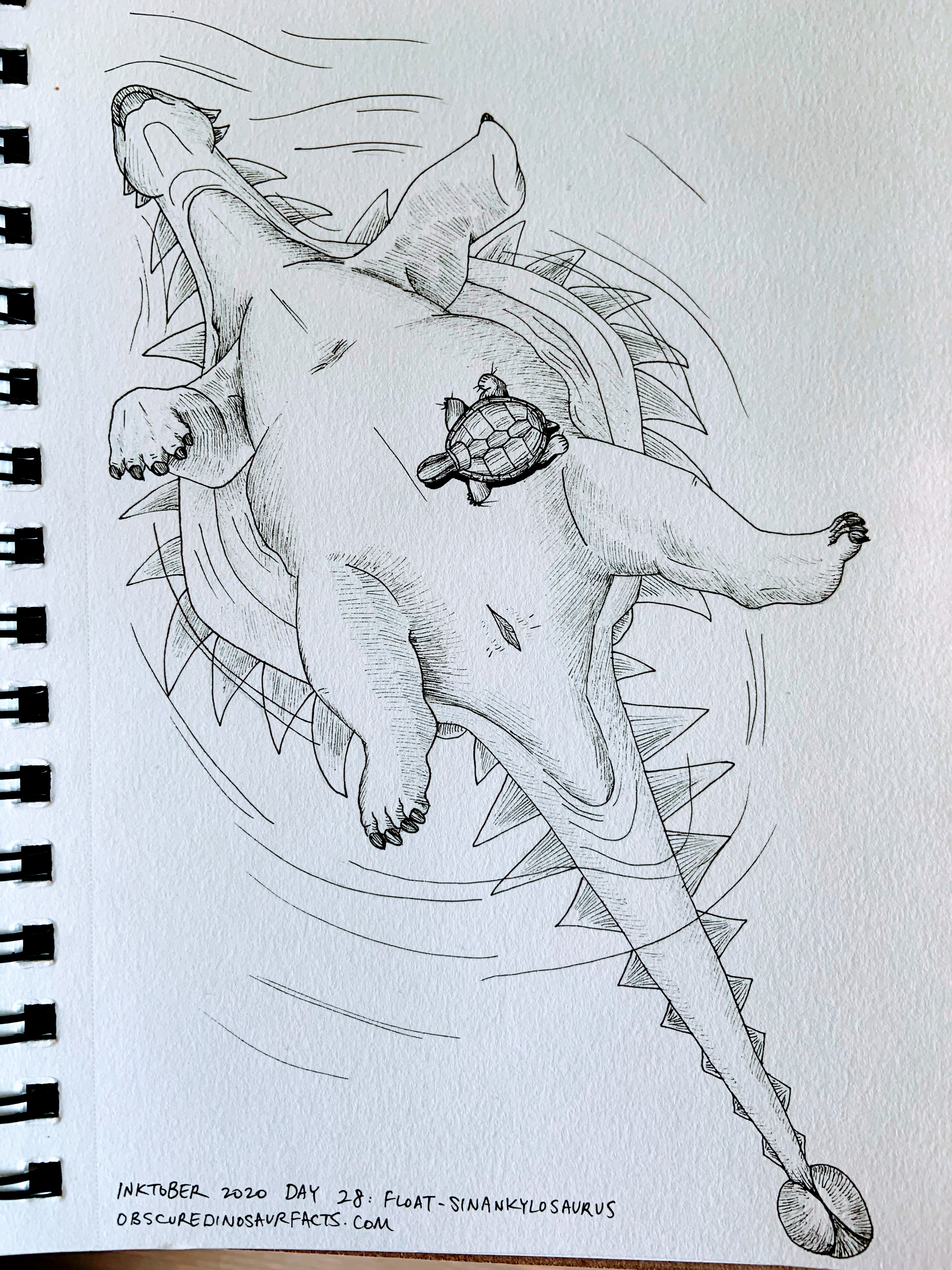

Day 28: Float

Did you know that ankylosaurs (the armored, sometimes club-tailed dinosaurs) almost always fossilize upside-down? It’s because of a phenomenon called “bloat-n-float”. If a dead ankylosaur ends up in the water, the gases that build up in its belly during decomposition combined with the heavy osteoderm armor on its back cause the animal to flip over. Eventually, the gases are released (sometimes explosively) and the carcass sinks and possibly fossilizes.

Here, a Sinankylosaurus corpse floats in a lake. A nanhsiungchelyid turtle climbs aboard to rest.

Day 29: Shoes

You didn’t think I’d be able to relate “shoes” to dinosaurs, did you? Well, here is Citipes (meaning “fleet foot”), a caenagnathid oviraptorosaur who has put his foot through a beehive. Was it on purpose, to eat the wax and grubs? Or was it a discarded hive he accidentally stepped in?

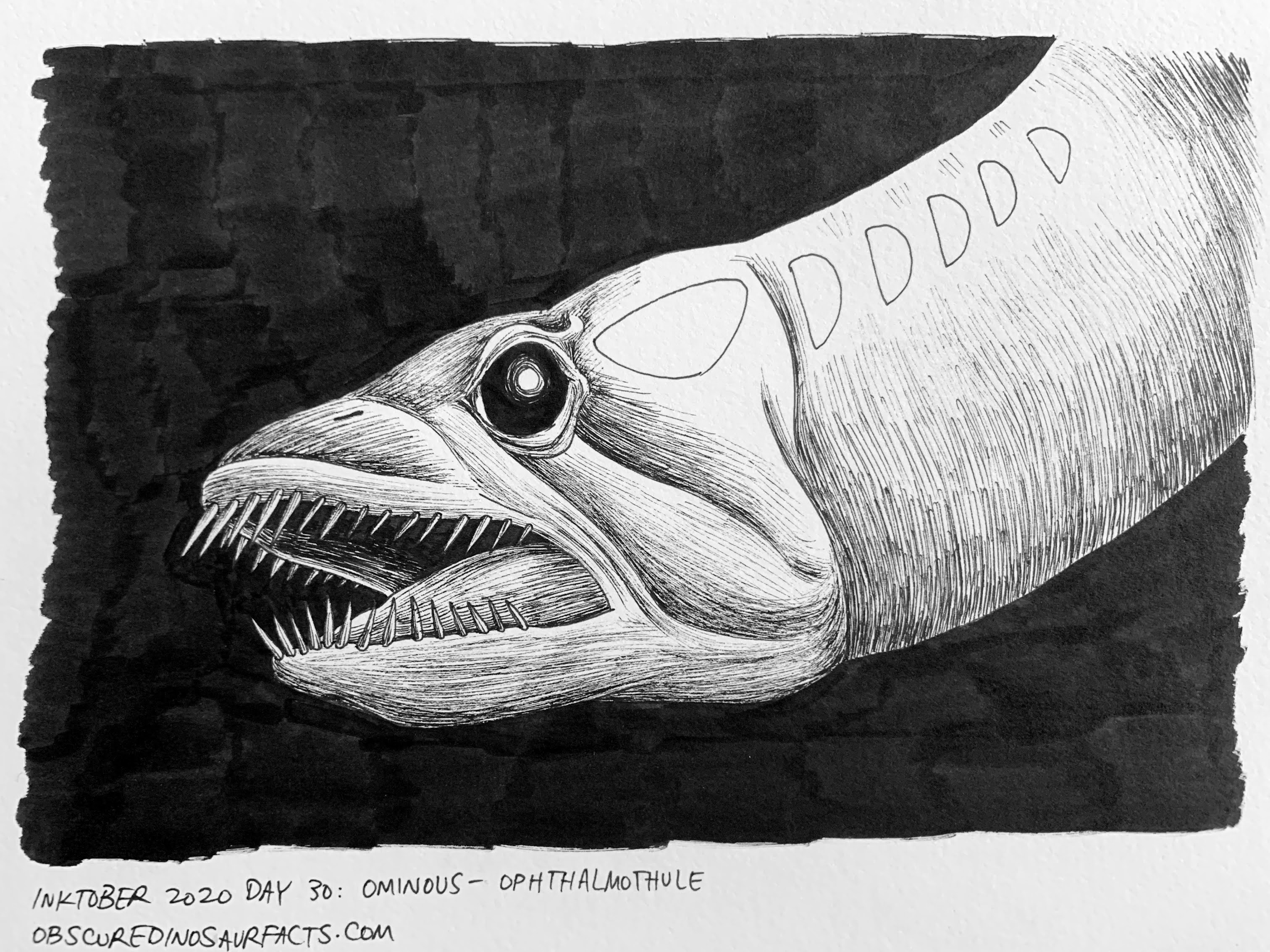

Day 30: Ominous

That’s no fish–it’s Ophthalmothule, a new cryptoclidid plesiosaur (one of the “Nessie” type aquatic reptiles). It had huge eye sockets and was found in far northern marine deposits, indicating that it was an abyssal or nocturnal hunter.

Deep-water animals are always so scary. I gave mine some bioluminescent spots so he can see a bit, but I’m not sure how realistic that would be for a diapsid reptile. I also fear I may have made him too fishlike. I was going for a fish-convergent face shape, but it ended up looking kind of just like a barracuda.

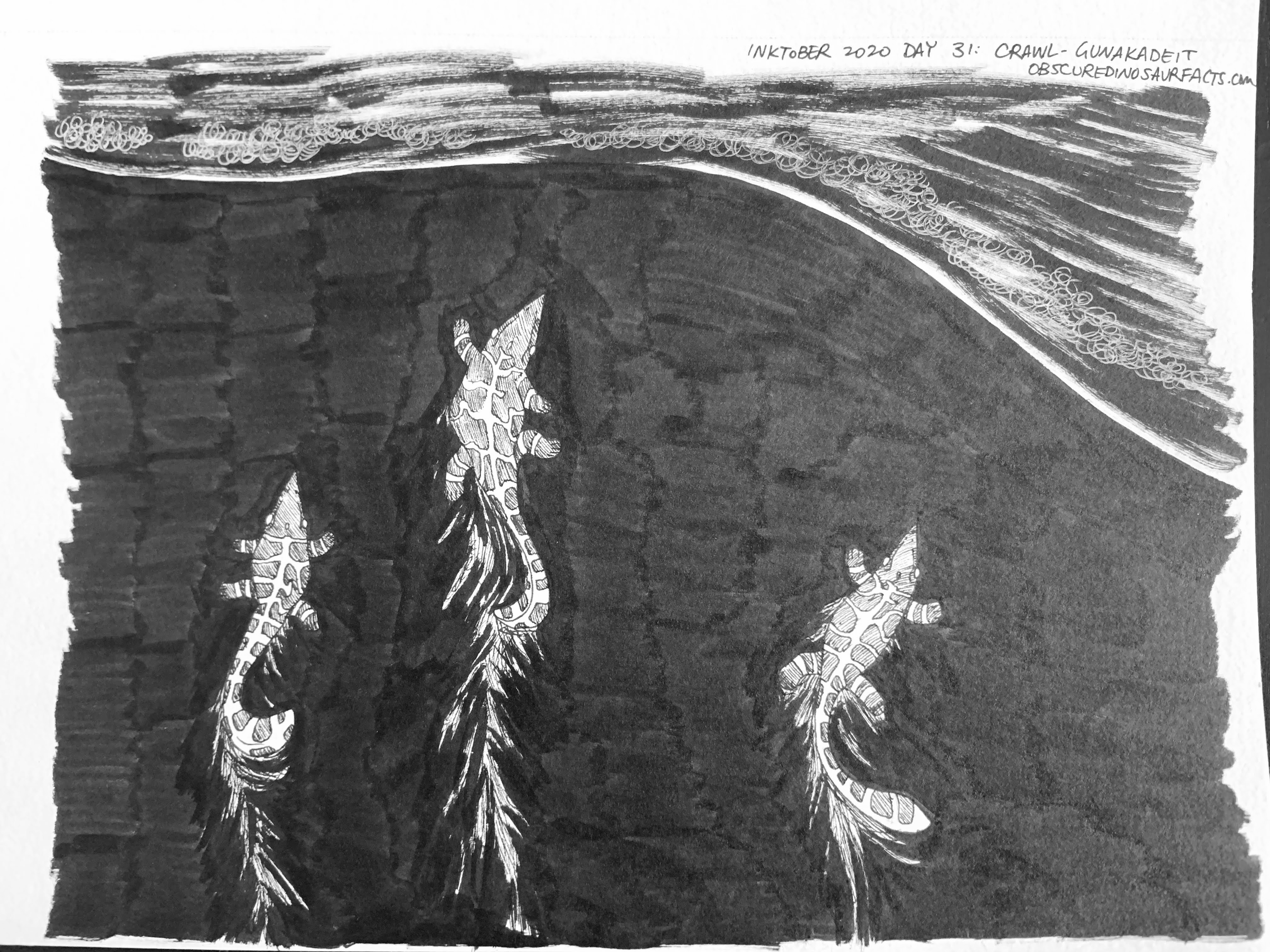

Day 31: Crawl

Gunakadeit was a thalattosaur from Late Triassic Alaska. Thalattosaurs were a mysterious lineage of diapsid reptiles adapted to an aquatic lifestyle that only existed in the Triassic, that weird interbellum period between two of the Big Five mass extinctions, the Great Dying and the T-J boundary. It’s thought that they laid soft-shelled eggs like many other diapsid reptiles, and thus would have had to haul out onto land to bury their clutches like modern sea turtles. The young, when hatching, would have then crawled to the sea, possibly attracted by the moonlight, which is what these ones are doing now.

Conclusion

Even though I hadn’t really touched traditional media since last Inktober, I think all the digital painting I’ve been doing has paid off. This year’s drawings are much more detailed and realistic than last year’s, and I also incorporated a lot more views other than side views, which I think makes the drawings feel more active and alive. That’s not to say there’s no room for improvement–there are numerous things I’d change in each piece if I were to do it again. However, overall I’m really happy with this year’s haul of ink.

Reddit has again been very supportive, including my friend from last year, u/jupiter1390, who did a lot of Cenozoic mammals this year and showed off their command of light and shadow. The one r/Dinosaurs enjoyed the most was actually Day 28, Float–I think the divide between those who thought it was just a dinosaur peacefully backfloating and those who read the title and realized it was actually a macabre scenario drove some controversy and thus more engagement. A close runner-up was Day 8, Teeth, which I think people thought was an interesting infographic.

Focusing on Mesozoic reptile novataxa ended up being a fun challenge, and I’ll probably do something similar next year. Last year doing something like that I think would have been too restrictive, since I was just getting my paleoart legs under me, but now that I’m more familiar with the anatomy and inferred behavior of more extinct clades the shorter list helped me narrow my choices of subjects each day.

Thanks for looking! Stay tuned for more digital art coming soon.