In public school, I recall learning about different types of rocks and the basics of Linnean classification (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, etc; mammals, birds, amphibians, etc) in elementary school, and some of the mechanisms of evolution in high school (alleles and Punnett squares, genetic drift, speciation, etc). But I never learned about the geologic time scale, I didn’t know anything about how specific animal groups were related to each other, and I’d never heard of many of the coolest extinct animals until I did my own research. However, I learned about the Revolutionary War on, like, five separate occasions. I think that’s a real shame, and I think kids, and later, science, and later, humanity, would benefit from adding natural history to the required public school curriculum.

My fiancé pointed out that this post is fueled by motivated reasoning–that is, I decided that because I like natural history it should be taught in schools, but since that’s not a very convincing argument, I came up with a bunch of additional, post-hoc reasons that it’s the right thing to do. This is a valid point, and I’ve since changed my mind about certain parts and incorporated that feedback into this post, but overall the arguments I describe below are also valid. So, please read with a grain of salt and ultimately make your own decision!

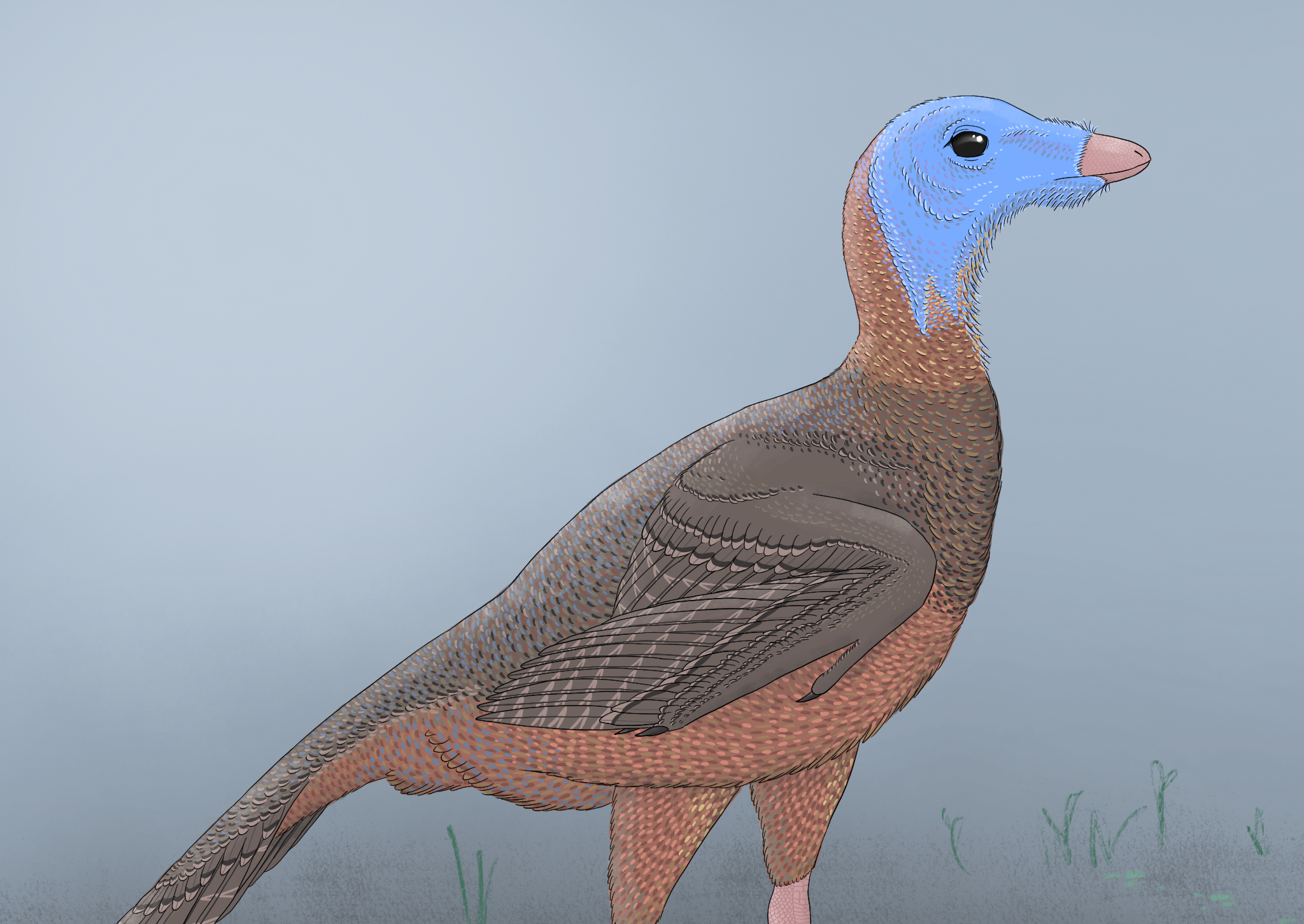

Children are naturally interested in dinosaurs

Many children love dinosaurs and do their own research to the best of their abilities. I certainly did at some point during my childhood (I decided Parasaurolophus was my favorite dinosaur just because I liked saying its name, and I spent awhile trying to figure out what was the biggest known dinosaur–not an easy feat pre-Internet). However, this drive to learn burns out if not enough information is easily available, or if what is available isn’t presented in a coherent manner. If natural history were taught in school, starting with dinosaurs at age six or so, kids would gobble up as much detail as they could memorize. I think not taking advantage of their innate curiosity at that stage to get them excited about learning is a huge wasted opportunity.

In paleontology, understanding how we know what we know is simple relative to a lot of scientific fields

Another problem with the way things are taught in school is that frequently, to save time, scientific discoveries, facts, and equations are presented as faits accomplis, with no discussion of how scientists came to those conclusions. Lab classes are supposed to address this issue, but instead of showing students how to apply the scientific method, it shows them how to follow instructions, and if the experiment fails, you probably did something wrong rather than discovered something new. How we know what we know in chemistry, physics, and molecular biology is often difficult to intuitively grasp due to the microscopic or blink-of-an-eye nature of the mechanisms at work. At some point, the student just has to trust the teacher that the atoms in her solution exist and are behaving the way she’s told they are. However, paleontology is a fortunate exception–almost everything is large-scale and relatively easy to understand and visualize. We know what sort of soft tissue overlaid a bone by looking at its texture and comparing it with living animals. We how animals would’ve moved by looking at the shapes of bones and their sockets, and trying to move them around. We know what an animal ate by looking at what shape of teeth it had, and what sort of wear marks are on them. I think a lot of this stuff could be easily learned and digested by young kids, who would get a taste of the scientific method in a way that interests them.

Understanding the relationships between everyday animals provides a better appreciation of nature

Given the situation we find ourselves in today–of irreversibly changing climate, widespread destruction of ecosystems, and rapid depletion of natural resources–I think it would help if more adults had a heightened appreciation of the natural world. Making ecological conservation a priority is something that we must do, or else face certain death. I think if people had a stronger emotional attachment to nature, this would be more likely to happen.

But why does learning about natural history give people a better appreciation of nature? I think there’s a big difference between seeing a landscape and thinking it’s pretty, and seeing an ecosystem and understanding all the complex and wonderful interactions that make it tick. Knowing what goes on behind the scenes and why animals and plants are adapted the way that they are turns the landscape into something interesting, alive, and interactable. At least, giving myself a crash course in natural history had this effect for me. As Thomas Huxley (a 19th-century naturalist famous for championing the theory of evolution as “Darwin’s Bulldog”) once said, “To a person uninstructed in natural history, his country- or sea-side stroll is a walk through a gallery filled with wonderful works of art, nine-tenths of which have their faces turned to the wall.”

Learning about evolution in context makes it stick better

As I wrote above, I learned about natural selection as a process taken out of context in high school. I learned about the founder effect using differently colored Skittles, and as I’ve stated in a different post, was given the example “dolphins and penguins” as an example of convergent evolution. Essentially, everything was presented as a free-standing mechanism with no context or history or real-world examples. They didn’t tell us that whales evolved from deerlike ancestors or that modern sloths and crocodylians are actually aberrant members of their respective clades.

Because of the lack of context, I think a lot of people leave with a very poor grasp on how evolution can be expected to work, if movies and books are anything to judge by. It’s not made clear that Linnean clades and actual descent are the same thing–that a rabbit is truly your bajillionth cousin. (Every human is at maximum your 3400th cousin, by the way.) The old fallacy of “The Great Chain of Being” (that evolution is linear and leads inevitably to humans, a la the movie Evolution) and the misinterpretation of the phrase “survival of the fittest” (it really means “fit” as in, an organism is a good fit for their particular environmental niche, rather than referring to some absolute “fitness” value that is always increasing) are perpetuated through incomplete and sometimes inaccurate teaching.

I think that if students learn about real-world examples that actually happened that illustrate the more abstract concepts associated with evolution, they will leave with a better intuitive understanding of how it can and can’t be expected to work.

But why do we care if people understand evolution? Well, we seem to already care, given that it’s part of the curriculum. Providing some natural history as context would just improve what already is supposed to be being taught.

Exposing kids to as many fields as possible increases the likelihood they’ll pursue something they’re interested in as a career.

With the way things currently stand, applicants to many four-year colleges are required to state a chosen major on the application, and often have to jump through hoops later if they want to change it. It’s a bit absurd to force kids to make such a permanent decision–not because they’re too young to know what they’ll be interested in later, but because they may never have been exposed to physics, psychology, engineering, or computer science. What if one of those is the thing they’re born to do?

To this point, I think curricula could be improved not just by including natural history, but also by the inclusion of all those other subjects I listed above. But what subjects would be cut to make room for these additional requirements? Read on…

Why are things like this?

Part of the problem is that every school subject is treated as deserving equal attention as every other. So over the years, students will spend as much time learning science as learning history; yet there is way more relevant science to learn, so portions of history get rehashed over and over to take up time while portions of science remain totally neglected. (It’s a similar problem to how most colleges treat every undergrad degree as requiring equal time to complete. How long does it take to learn to be an electrical engineer? Four years. How long does it take to get an English degree? Four years. It seems clear that if you reasoned from first principles for each degree, you wouldn’t come up with equal time for all of them.) If we adopted a different, less compartmentalized method of determining the curriculum, maybe we could cover more cool science topics than just natural history, like making basic computer science, physics, psychology, and others mandatory.

Another part of the problem may be that geologic time offends the sensibilities of creationists, so they vote to keep it from being taught in schools. However, I did learn about the mechanism of evolution out of context in high school biology class, so perhaps this isn’t really a reason for the omission. But maybe creationists have been able to limit the time spent on evolution to a small part of the curriculum?

The last, and probably most important reason on the individual level, is that it’s difficult to find teachers who are qualified to teach such a variety of subjects. If you’re requiring an introduction to computer science in sixth grade, you’ll have to find someone with a computer science degree and a teaching credential willing to work for a middle school, for every middle school in the country. Possibly people like this don’t even exist. I don’t know the details of teacher recruitment and how it differs in different regions, but from what I’ve heard it’s quite difficult to find competent science teachers because most people with science degrees are employed in their field, which tends to be more lucrative than teaching. So, just changing the curriculum requirements at the top level may actually make things worse, since underqualified teachers will be forced to teach subjects they’re not familiar with. In fact, in 2010 Congress established the Committee of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) Education (it’s bipartisan and still active under Trump), which enacts these type of top-down curriculum changes without addressing the logistical problems associated with carrying out their orders.

The solution to that problem is to pay teachers more, so that a teaching career is as lucrative as an engineering career, but that’s a whole ‘nother can of worms. It would require an overhaul of the existing public education and taxation schema, which seems unlikely given America’s general affinity for (and prior success under) capitalism.

But all is not lost! If you’re a scientist or engineer reading this, you could help by reaching out to teachers and parents and offering to talk to their classes about what you do; if you’re a parent or teacher, you could reach out to any scientists or engineers you know, or consider bringing your kids or students to museums, aquariums, or other places where science communicators can help you educate. Given the difficulty of the problem and the importance of STEM education, maybe a grassroots, individualistic approach is the best option. And besides, it’s often individual connections and relationships with mentors that influence the path a kid will take.

I’m writing all this as a lowly blogger, based on my own personal experience. I’m not a teacher, policymaker, or even a parent. If you have experience with STEM education, the problem of recruiting STEM teachers, or just have something topical to say, please reach out. I’d love to hear more opinions and background on this issue.