Niche partitioning is a really fundamental concept in ecology that influences the way organisms live, compete, and evolve. In this post, I’m going to go over what exactly it means, how it works, and some interesting fossil examples.

Overview

What is a niche?

A niche is a role within an ecosystem that a species can fill. It describes both the way the environment affects the organism, such as through resource abundance, predator habits, or disease, and the way the animal affects the environment. For example, the role of Fleet-Footed Grazing Herbivore in the biome California Chaparral is filled by the mule deer, while in the similar Australian Scrubland biome, this role is filled by the kangaroo. (Deerlike terminology is sometimes applied to kangaroos, with the males being called bucks and the females, does. I’m not sure whether this has to do with percieved niche or morphological similarity with deer or if it’s just coincidence.) Desipte the drastic differences in appearance, lineage, and functionality between deer and kangaroo, they are able to interact with their similar environments in much the same way. If deer and kangaroo coexisted in the same place–say, if kangaroos were brought to California–they would compete with one another.

Here’s a temporal example rather than spacial. The role of Large Grazing Herbivore in the ecosystem American Plains used to be filled by the American bison, but is now filled by the domestic cow. Cows and bison digest grass and produce dung that acts as a home for grubs, fungi, and microorganisms, and fertilizer for new grass to grow. They stir up bugs by walking through grass, which creates opportunities for insectivores to follow behind and pick them off. By forming depressions in the ground where they lay down, they also create little rainwater ponds that are important for frogs. All these functions are part of the niche, but despite its complexity two different types of animal can perform almost the same role.

If two species fill the same niche in the same place at the same time, they will compete for resources until one of them goes extinct or finds a new niche.

In Friends, when Elaine finds a new group of friends, they fill all the same niches as her old group. So, when George asks to join the new group, he’s told “we’ve already got a George.” If two Georges are in the same group at the same time, they would compete for attention, laughs, and other scarce resources. Elaine can’t have that happening!

Niche paritioning

As I stated above, two species attempting to fill the same niche at the same time ends with one of them going extinct or finding a new niche. The latter is known as niche partitioning: one or both species previously competing with each other will, in the words of our esteemed princess, “find something new”. This can happen by exploiting a different food source, moving to a new habitat or location, or changing one’s temporal habits (e.g., becoming nocturnal). If two groups continue to diverge due to increased niche partitioning, eventually they will become different species, in a process called speciation. Speciation is the basic unit of all evolution. (Every genus was once a species, every family was once a genus, etc.)

The number of niches available in a given environment is not set in stone; species are always creating new niches, either by doing something novel or by taking advantage of an opportunity created by another species that’s doing something novel. For example, trees first became a thing in the Carboniferous Period, about 300 million years ago. Trees created a new niche for themselves by raising their photosynthetic parts on stilts, allowing them to greedily capture more sunlight than their neighbors–but as a side effect, they also created a whole new environment for other organisms to live in, and a new food source (wood) for other organisms to figure out how to eat.

How does this work in practice? There are many different situations that can kick-start niche partitioning and subsequent speciation, but they generally fall into three categories: allopatric, peripatric, and sympatric speciation. Allopatric (“other fatherland”) speciation occurs when two populations of a species happen to get geographically isolated from each other (this is what happened to chimps and bonobos), as by mountains rising, drought shrinking a lake into two smaller lakes, or a river changing course. If the conditions on either side of the barrier are different, the two populations will experience different selection pressures, and then if the barrier is later removed, they’ll now interact with their environment in a slightly different way, and competition between the two newly rejoined populations will force them to further differentiate themselves (or, if they’re not different enough yet when the barrier is removed, the populations will just rejoin and not speciate). Sympatric (“together fatherland”) speciation occurs when a population within a species moves to exploit a newly available resource, like in the tree example above. It’s not totally accepted how or even if this happens, since there’s nothing to really prevent the two populations from interbreeding; sympatric speciation may require an allopatric event to kick-start it. Peripatric (“near fatherland”) speciation is a middle ground situation, in which a species covers a large enough area that the extreme ends can diverge even when the middle is still interbreeding.

The way that organisms interact with each other and their environment is very complex, and trying to categorize interactions into a finite number of groups is probably futile. It helps to have names for phenomena so we can better observe and talk about them, but there are lots of situations that fall outside or in between categories.

Special cases

Ontogenetic niche partitioning

A special case of niche partitioning is when the juveniles of a species have a different lifestyle than the adults, known as ontogenetic niche partitioning. For example, baby crocodilians subsist on a diet of bugs and frogs, while adult crocs famously go after zebras and other megafaunal prey. Subadults eat snakes, mammals, turtles and fish. The constantly shifting diet allows one species to exploit numerous niches in an environment and by doing so, increase the maximum population that environment can support. Only some species do this–mainly the ones that have a large size difference between juveniles and adults.

An even specialer special case is that of metamorphic niche partitioning, which refers to the different lifestyles of the various life stages of metamorphosing organisms. A caterpillar experiences very different selection pressures than a butterfly, but a change in the way the caterpillar lives its life may affect the future fitness of the butterfly. It’s a strange situation–evolution can be pulling a species two totally orthogonal ways at the same time.

Niche assimilation

In certain cases, ontogenetic niche partitioning by a dominant species can be so extreme that one species can “assimilate” multiple niches, and prevent other species from competing in any of them. Take Tyrannosaurus for example–its juveniles were much lankier and built for speed than the tank-like bone-crushing adults, and the juveniles were much more numerous in the environment. This actually drove species-level diversity down in their environment, due to juvenile Tyrannosaurus out-competing other midsized theropods like megaraptorans, large dromaeosaurs*, and even other smaller tyrannosaurs. Compare this to the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, in which carnivore diversity was much higher, since the giant theropods that became the best at niche assimilation hadn’t arisen yet.

* You may be thinking, “What about Dakotaraptor?” Dakotaraptor was actually super rare in Hell Creek, and there’s still doubt as to whether it’s a chimera or not. Perhaps they were more common someplace else where large tyrannosaurs didn’t go. Or perhaps they just eked out a living in the shadow of Tyrannosaurus and were just never very numerous.

Fun fossil examples

Tanystropheus

Tanystropheus was a very long-necked archosauromorph from Middle to Late Triassic Europe. Imagine a lizard body with the neck stretched to giraffelike proportions. The best-known species of Tanystropheus is T. longobardicus, which is known from dozens of specimens that come in a “large type” (up to 6 meters long) and a “small type” (less than 2 meters long). New research shows that rather than the small ones being the juvenile form of the large ones, they are morphologically distinct enough to be different species, and their tooth and size disparity indicates they probably niche partitioned in order to coexist. The large species, renamed T. hydroides, would have eaten fish and cephalopods (this is also known from preserved gut contents) while the smaller species, retaning the name T. longobardicus, would have eaten soft-shelled crustaceans.

Mosasaurs

Mosasaurs were a group of marine lizards that rose to prominence at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Most were fish-eaters or apex predators with sharp, conical teeth, but some, like Globidens, employed the completely different strategy of durophagy, or crushing hard-shelled prey, developing spherical teeth. Being a specialist on prey other mosasaurs couldn’t touch would have allowed it to coexist without competing with other mosasaurs.

Above: Globidens’s strange spherical teeth.

Above: The newly described medium-sized mosasaur Gnathomortis interacts with the giant mosasaur Tylosaurus. It was common for many species of mosasaur to coexist in the Late Cretaceous. They differentiated themselves both by modifying their teeth and jaws, as in Globidens, but also by modifying their swimming style and diving capabilities. For example, Tylosaurus is unusual in having longer back flippers than front, indicating it may have swum quite differently than other mosasaurs, which have a more sharklike body plan with the front flippers dominating; and a newly described species of Plioplatecarpus has huge eye sockets, an adaptation for deep-water hunting. A marine environment is 3D, introducing another dimension along which organisms can niche partition!

Oviraptorosaurs

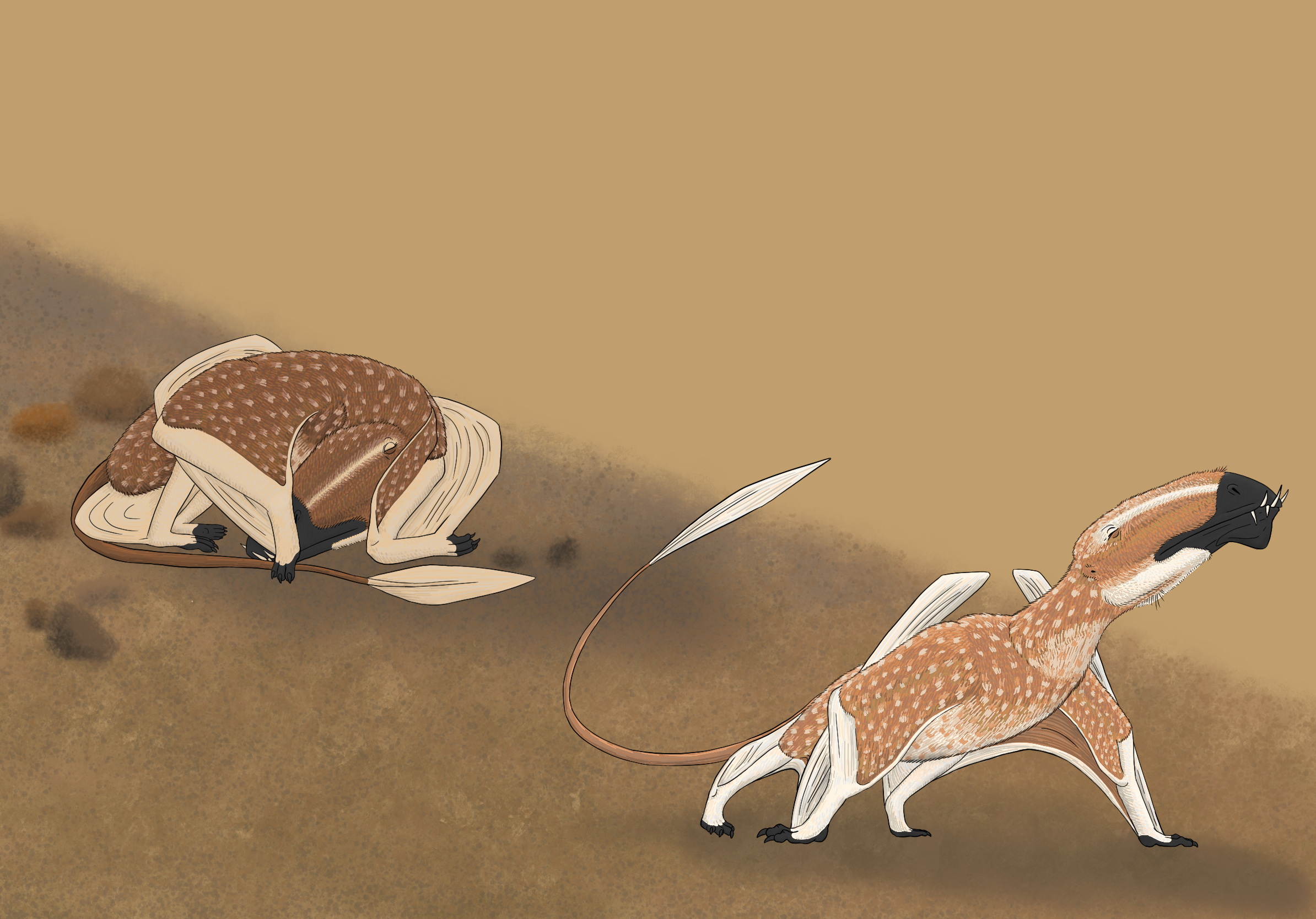

At the very end of the Cretaceous Period in southern China, there lived at least six genera of oviraptorosaur (the beaked, birdlike theropod dinosaurs): Banji, Ganzhousaurus, Jiangxisaurus, Nankangia, Huanansaurus, and Tongtianlong. Since the formation they come from, Nanxiong, is poorly dated as of yet, it’s possible that not all of these oviraptorosaurs truly lived alongside one another, but rather each type was replaced by the subsequent type. However, there is a lot of diversity in body size, crest shape, and beak shape among these taxa, indicating that at least some of them probably did coexist, and would have had to have niche partitioned in order to do so. Oviraptorosaurs are thought to have ancestrally been omnivores, so later radiations of derived groups could have specialized on one of the foods that would have made up their ancestors’ diets: fish, shellfish, nuts, leaves, fruit, insects, or small prey. Modern birds show examples of beak adaptations for tackling all these types of food, so perhaps something similar was going on with the Nanxiong oviraptorosaurs.

Sauropods

Similarly, an abundance of sauropods (the long necked dinosaurs) coexisted in the Latest Jurassic Morrison Formation, in what is now Colorado: Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Barosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Brachiosaurus. The first four genera I listed are all diplodocids, the horizontally-necked, whip-tailed sauropods, while the last two are macronarians, the more vertical-necked, short-faced sauropods. It’s not fully agreed upon which dinosaurs used which feeding habits in order to niche partition, but these are the roles that have been hypothesized:

- Branch stripper. Some sauropods, probably diplodocids, would have lightly grabbed a branch by its base and yanked back, stripping all the leaves off.

- Chomper. Others, probably macronarians, would have just chomped the branch along with the leaves.

- Lawn mower. Some, diplodocids again, could have used their long necks to stand in one place and reach low vegetation like bushes and ferns in a wide radius without having to move much.

- Cycad specialist. Cycads are an ancient lineage of plants, superficially similar to palms, that grow giant cones, which are too big to be eaten and dispersed by any animal today. Sauropods, especially macronarians, would have been the perfect agent to chomp the cones and excrete the seeds miles away.

Above: Camarasaurus chomps on a juicy cycad cone. This is a case of Megafaunal Dispersal Syndrome–a plant coevolving with a specific animal for pollination or dispersal, and when that animal goes extinct the plant appears maladapted–which I’ve discussed in my post on evolutionary anachronisms.

Final notes

The page image is the dimorphodontid pterosaur Caelestiventus, which differentiated itself from other dimorphodontids by becoming desert-adapted. No other primitive (non-pterodactyloid) pterosaurs are known from desert environments.

How do you pronounce “niche”? I personally say “neesh” but “nitch” and “neetch” are also acceptable. Comments on a postcard…

Image credits: GeorgeTanystropheusGlobidens Gnathomortis and TylosaurusCamarasaurus and cycad