Inktober took up most of my artistic energy for the past couple months, but here’s the other digital stuff I’ve been working on.

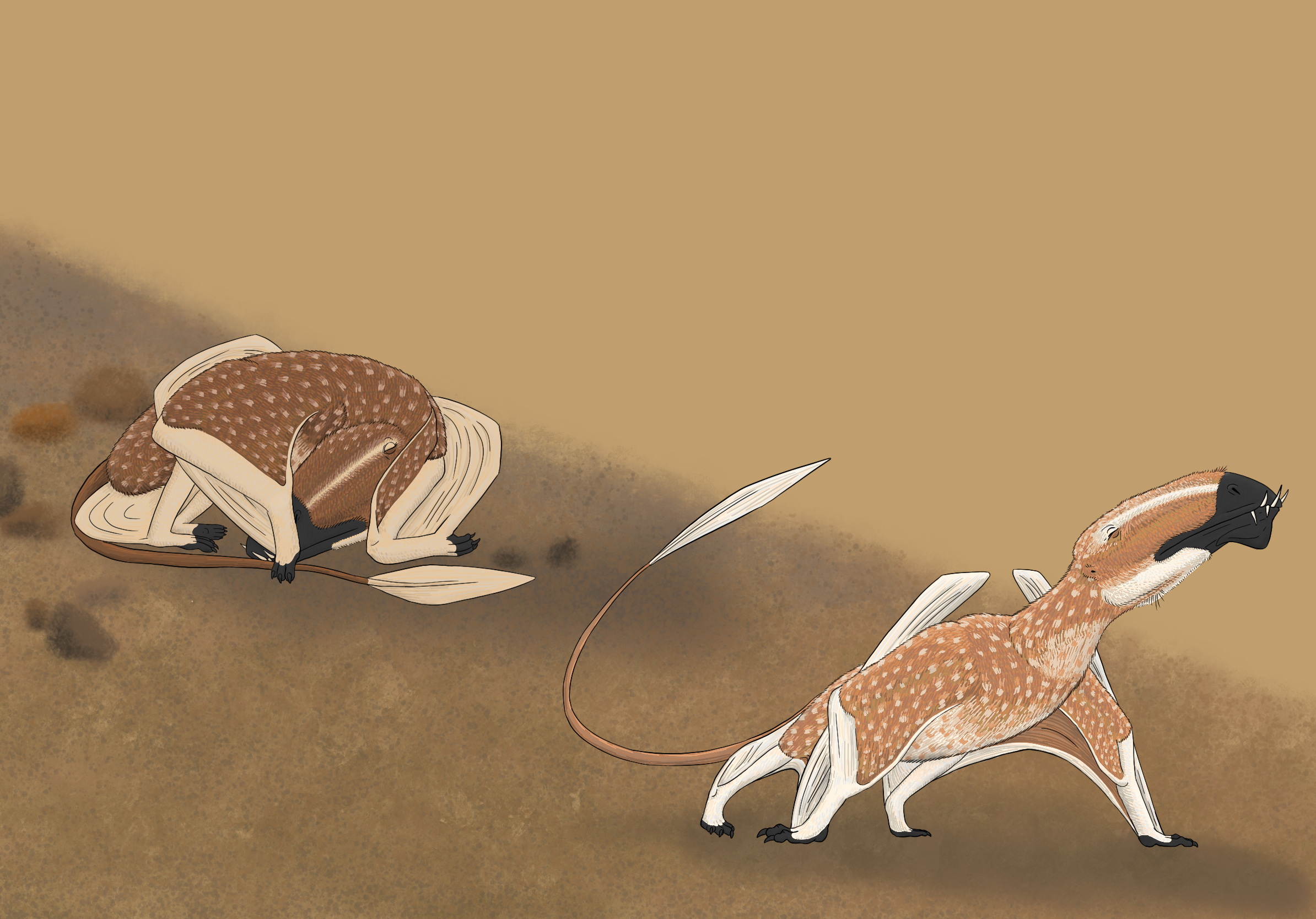

Caelestiventus (meaning “heavenly wind”–what a great name for a prehistoric beast) was a dimorphodontid pterosaur from Late Triassic Utah, which was then a desert environment. It was large for an early pterosaur and probably specialized for its extreme environment, indicating potential higher diversity among this group than we’d previously thought. I was inspired by the way vampire bats move on the ground (check out the documentary series “Night On Earth” for incredible footage of vampire bats preying on fur seal pups and all kinds of other cool stuff)–their wings fold up and you can’t even tell they could fly until they do–and wanted to see if I could figure out how these weird, membrany animals might look in various poses. I’m not sure I’m happy with how they turned out, but I learned a lot while doing it at least. I think this is a brother-sister subadult pair, the male having the large chin crest.

Inspired by one of the end-of-year questions from 2018 on the Common Descent Podcast, I thought I’d tackle the speculative evolution problem, “Which is cooler: a snake convergent with crocs, or a croc convergent with snakes?”

Champsoidoboa (“croc-like boa”), in yellow, is a descendent of a green anaconda, which are already semi-aquatic predators. Over time, it became more of a shoreline ambush predator, making its body shorter and re-developing its spurs as much as it could in order to give its strike more oomph. Its jaws are very modified from its ancestor’s as well, with much more bone fusion, less flexibility, and conical, rather than needle-like, teeth.

Pseudophisuchus (“false snake croc”), in blue, is a descendent of the saltwater crocodile, which became more aquatic over time, elongating its body in order to better undulate and shortening its face like Dakosaurus. Perhaps it lives in large reefs, and reduced its legs so it could fit into tight spaces. Someone pointed out that it looks like Typhlosion without legs, which now I can’t unsee.

I think Pseudophisuchus is more of an exciting creature design, but Champsoidoboa is more plausible.

It’s Lystrosaurus declivis, the little stem-mammal that conquered the world after the Great Dying, feeding on a leafy sprout in the Early Triassic. To me, Lystrosaurus seems like the synapsid version of a turtle–short-faced, slow-moving, hardy, vegetarian, and able to hibernate.

I was trying out an amazing new foliage brush set by TamberElla. My skill with them is poor–don’t judge the brushes by me, haha.

In 2016, some very large fossilized scratch marks were uncovered in the Dakota Sandstone of Colorado that were named Ostenichnus bilobatus and were diagnosed as being part of a very large theropod’s mating display. While it’s hard to confidently match a trace fossil with a trace-maker, Acrocanthosaurus is a good bet, since it matches the time, place, and size. This dinosaur could weigh up to 6 tonnes, so I couldn’t give him a full fluffy coat, but since it presumably engaged in lekking behavior, I wanted to give him some flashy feathers to go along with his ritual ground-scraping. The feathers, of course, are inspired by the golden-collared manakin, a sub-one-ounce bird from Panama. I just thought the raisable/lowerable beard crest that’s sort of the inverse of a jay’s head crest, was really interesting.

This is my first attempt at photo manipulation, and I’m pretty happy with how it turned out. Remember my photo of a willet on a mud-flat, catching an invertebrate? I thought it would be a good template for showcasing the new tiny mud-probing pterosaur, Leptostomia. I had a lot of freedom to make his anatomy match the willet’s, since Leptostomia is only known from a skull. I also gave him a heron’s kinked neck for a fast, lever-driven strike.

Some research by Emerald Bender presented at SVP this year indicated that ceratopsians’ horns and frills were probably strictly decorative, and not often used in intraspecific combat or defense. While this has been assumed for awhile about the frills, which are sometimes paper-thin and have a ridiculous amount of variation between genera, the horns being decorative is a new idea that implies fun coloration on the horns themselves. This is a portrait of the novataxon Stellasaurus in the style of artist Andreas Preis. MAN is this style time-consuming! I like how it turned out, but I’m not sure if I’m going to do any more of these. See my Deviantart page for a coloring-book version!

A kitsune mask? A dragon? No, it’s Proburnetia, the dog-sized bump-headed Permian biarmosuchian (a type of stem mammal). This animal had lots of bizarre bumps all over its skull, which I’m interpreting as anchor points for impressive horns, like how Pachyrhinosaurus is often depicted nowadays. This isn’t a new idea–check out this very draconic reconstruction. Biarmosuchians were cold-blooded, so they wouldn’t’ve had fur, but I tried to give it a snout reminiscent of mammals. The result is this highly fantastic, highly speculative dragon-tiger thing.

I decided to make my own interpretation of Andreas Preis’s style for this one and do patterns inspired by azulejos (Portuguese traditional painted tiles) in the colored regions instead of just overlapping striped ribbons. I’m not sure it’s any good; I think maybe I mixed too many styles and the result is incoherent. The overall shapes involved, composition, and coloration are reminiscent of Japanese kitsune or kabuki masks, which don’t mix super readily with the Portuguese azulejos.

Anyway, now I’m officially done with these. I also made this one into a coloring page if you’re interested in some paleo Zen time.

I was watching the original Walking With Dinosaurs (yep, I haven’t seen it til now! It holds up super well, would recommend) and when the British narrator said “Muttaburrasaurus” my fiancé said, “Nutter Butter Saurus?” and this was born. Have another Nutter Butter peanut butter Muttaburrasaurus!

Muttaburrasaurus was a large bipedal ornithopod from Early Cretaceous Australia. It was probably bulkier than this, and its nose was a little taller, but I wanted to exaggerate the peanut shapes.

I guess I’m making this a series. Maybe dieting is finally getting to me psychologically, so even when I think about dinosaurs I’m also thinking about junk food.

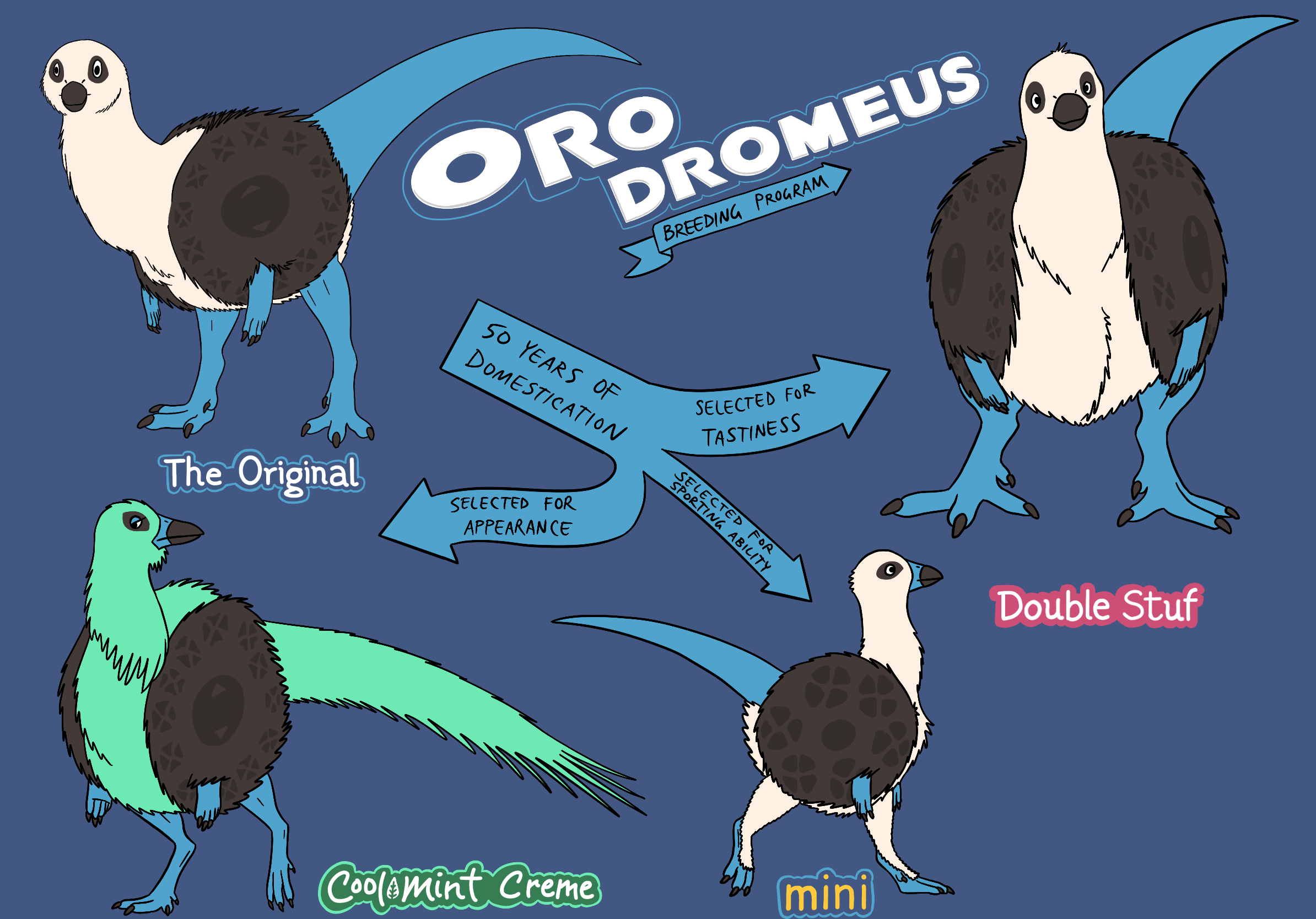

By the way, Orodromeus was a cat-sized burrowing parksosaurid ornithischian from Late Cretaceous Montana. Originally I thought I’d make the Oreo pattern into some kind of jaguar-like spots, but it ended up just looking exactly like an Oreo. Oh well.

Yep, this is getting out of control. Speculative evolution + dinosaurs + junk food = ???

Melanorosaurus was a sauropodomorph (ancestral cousin of the long-necked dinosaurs) from Late Triassic South Africa. It could reach weights of up to 1.3 tonnes. It was one of those dinosaurs that thought it was very classy but was actually found everywhere, like at Target.

Mymoorapelta was a basal nodosaur from Late Jurassic Colorado. Ankylosaurs would become the dominant armored herbivores later in the Cretaceous Period, but in the Jurassic they lived in the shadow of the abundant stegosaurs. This is the first one where the cookie is horizontal relative to the animal. I think he turned out looking pretty yummy, but not that much like a MoonPie.

Here’s some flavor text for the series: Orodromeus’s large litter size and short generation time allow it to evolve rapidly, resulting in many variants in the wild, especially leading up to winter when predators are more active as they prepare for hibernation. Breeders took advantage of these traits to create all kinds of breeds that should never have existed, like “Caramel Apple” and “Most Stuf” (the latter of which are almost always born with horrible deformities). On the other extreme, Muttaburrasaurus’s natural diet consists exclusively of fabaceous plants; it sequesters toxins from these in its dry, flaky skin to deter predators. This, combined with the difficulties presented by its specialized diet and low reproduction rate, means that it has resisted attempts at domestication despite its tastiness.

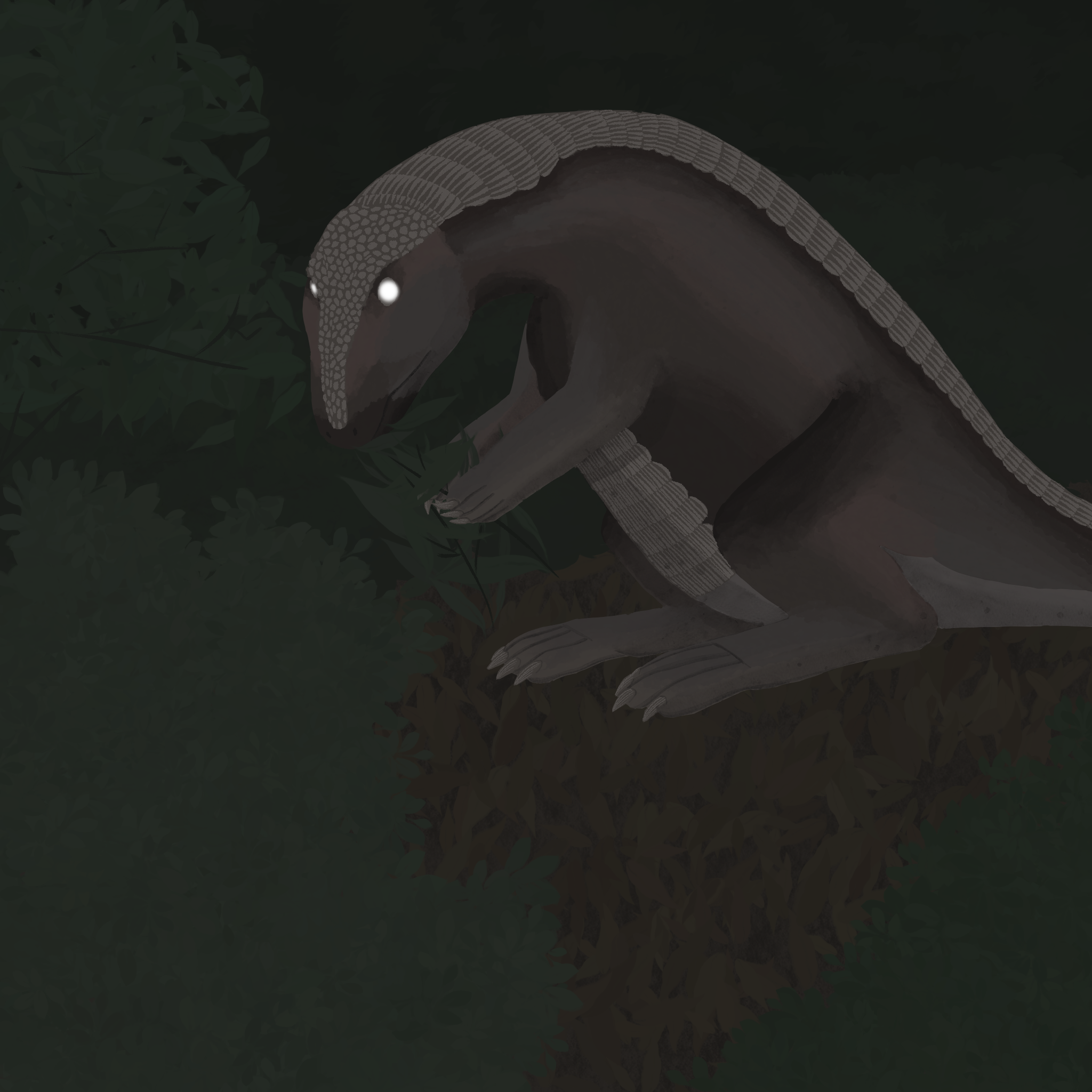

It’s Revueltasaurus, a little herbivorous pseudosuchian from Late Triassic Arizona, which I drew for my Chinle Biome Profile. I couldn’t find any art of this animal in an evironment rather than just on a plain background, so I created one. I thought that if it was herbivorous, it should be a little more portly than the way it’s often depicted, in order to have room for a long fermenting digestive system. There’s no evidence that it was nocturnal or diurnal, so I just went with nocturnal to shake things up a bit.

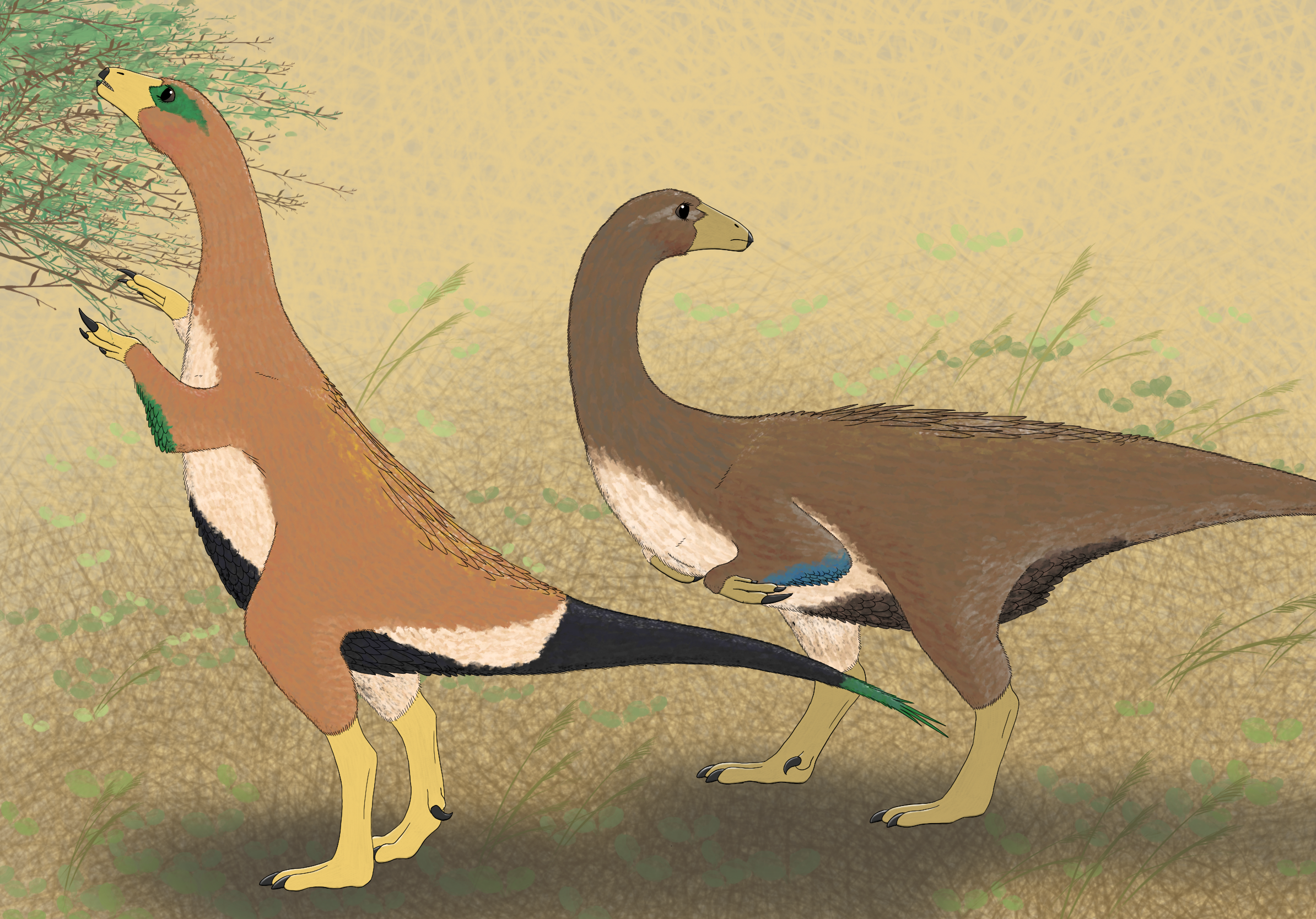

It’s Chilesaurus, the dinosaur of problematic affinity from Late Jurassic Chile. It had theropod-like shoulders, sauropod-like limbs, ornithischian-like hips, and birdlike hands. This is another sneak preview of a future profile…stay tuned!

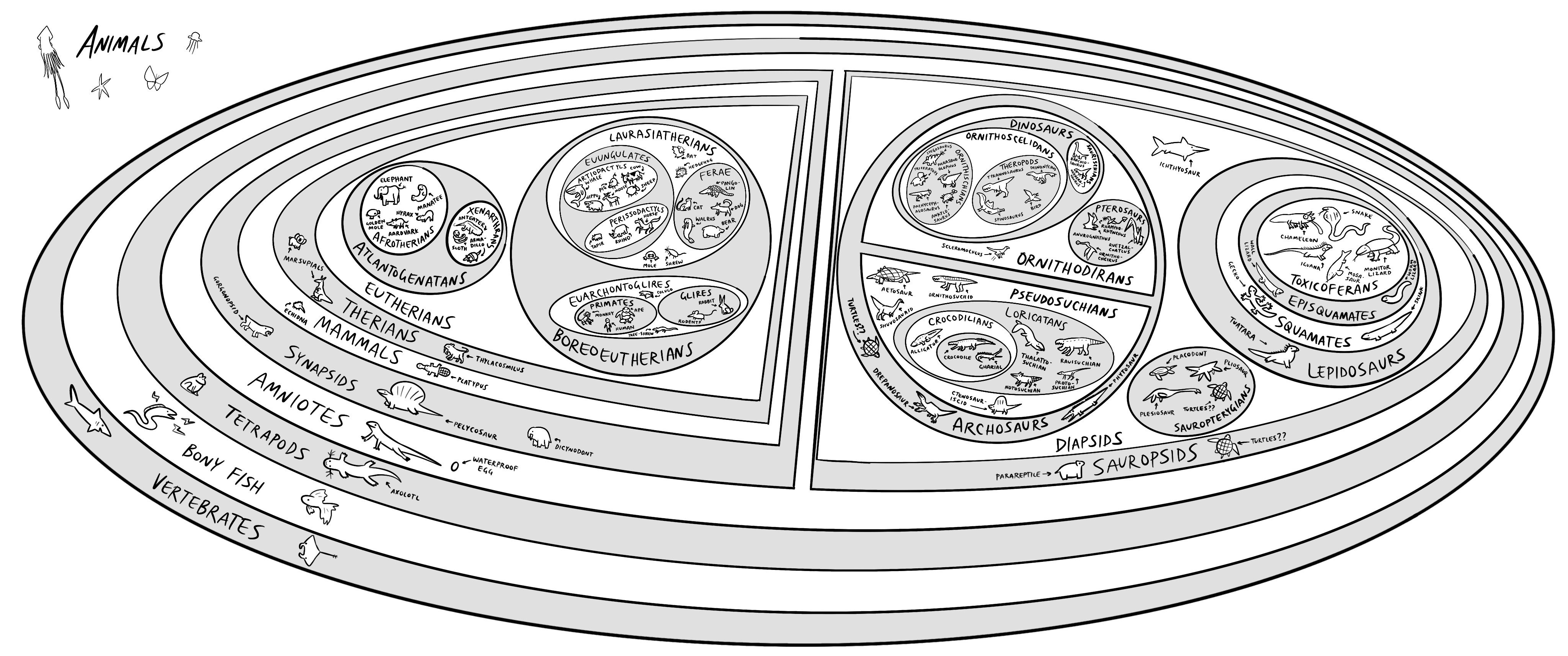

And now for something completely different: the tree of life! Except it doesn’t really look like a tree in this format, more like a strainer of life. This way, the definitions of paraphyletic and monophyletic clades are baked into the structure! Do any relationships here surprise you?

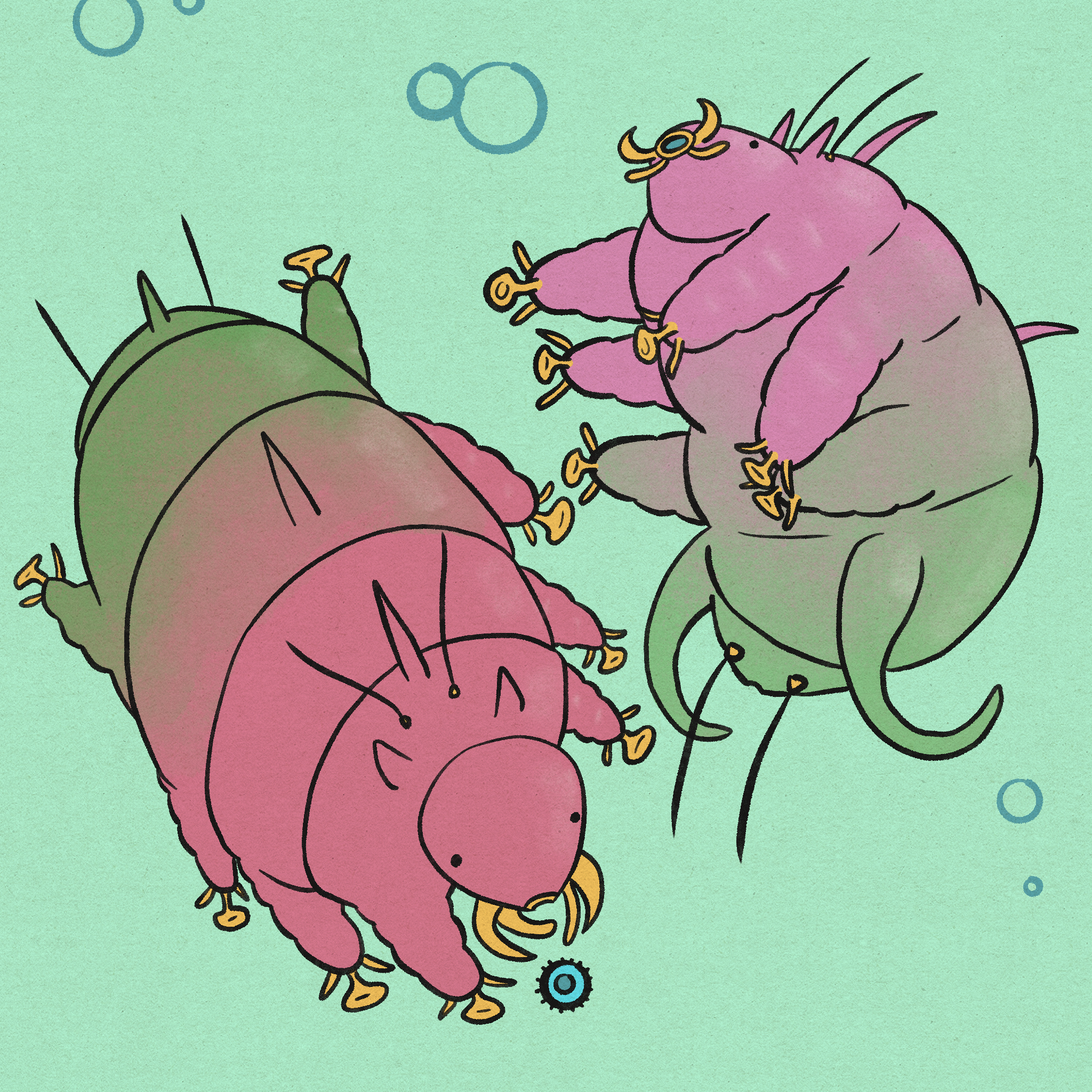

It’s the brand-new tardigrade relative, Sialomorpha dominicana, also known as mold pigs! Hundreds of these microscopic animals that lived during the Paleocene were found in Dominican amber, representing all stages of life. Some were even caught in the act of eating mold spores, hence the name.