In my first Paleo Biome Profile, I detailed the Early Cretaceous Yixian biota. In this post, I’ll do the same for the Late Triassic Chinle Formation, an ecosystem from a hundred million years earlier. I think it’ll be interesting to contrast the different animal groups and their interactions from the beginning and toward the end of the Age of Dinosaurs.

The Chinle Formation is located in the southwestern United States, spanning the badlands of Arizona, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Nevada. It covers numerous national parks, including Zion Canyon, the famous fossil location-slash-artist’s residence Ghost Ranch (the former home of Georgia O’Keeffe), and the creationist’s favorite fossil site, the Petrified Forest. (They believe that the upright-preserved fossil trees are evidence of the biblical Noah’s Flood.) While the environment is now a desert, 228 million years ago in the Late Carnian Epoch it was a warm, semi-arid climate criscrossed by many swamps, lakes, and rivers that frequently flooded.

If you remember the original Walking With Dinosaurs, the first episode, starring Coelophysis, Placerias, and Postosuchus, was set in Chinle. There were a couple other inclusions like Peteinosaurus the little pterosaur and an unnamed cynodont (early mammal relative) that are not known from Chinle, but it’s reasonable to assume that similar critters did live there. Just this year, the first cynodont from Chinle was described, called Kataigidodon, but it’s much too small to be the one depicted in Walking With Dinosaurs. If we keep looking though, eventually a candidate could turn up!

The plants at Chinle would have included a mixture of recognizable and foreign members. There were conifers like Araucarioxylon, the state fossil of Arizona, which could reach heights of over 60 meters and is closely related to the living kauri trees of New Zealand; ginkgoes, cycads, and ferns; and lycophytes, giant relatives of the modern quillwort. Flowering and fruiting plants wouldn’t appear for another 94 million years.

As a whole, the Triassic Period was unlike any other. Bounded on both ends by two of the Big Five mass extinctions, it was a time of recovery, radiation, and experimentation, much of which was prematurely destroyed in the Triassic-Jurassic extinction. Many animal groups rose and fell within this one period. For profiles on individual Triassic taxa, I’d recommend the blog WTF Triassic. There was so much wonderful weirdness going on at that time in Earth’s history.

While the Early and Middle Triassic were characterized by a cold, arid, somewhat post-apocalyptic climate, 234 to 232 million years ago there was a period of global warming and increased precipitation known as the Carnian Pluvial Event, which set the stage for the rise of the fauna we see at Chinle. In the Early and Middle Triassic, more basal animal groups were still dominant, like the temnospondyls (large amphibians), many types of small-bodied archosauromorphs (early relatives of crocs and birds), and stem-mammals; in the Late Triassic we see the rise of the archosaurs (crocodylians, dinosaurs, and their closest relatives). Many of the most famous Triassic creatures are from this time and place, including the well-known early theropod Coelophysis, big croc-mimic phytosaurs like Smilosuchus, and giant terrestrial crocodylians like Postosuchus.

Life In The Water

Since freshwater lakes and rivers were so abundant in Chinle, many of its terrestrial and aquatic inhabitants would’ve interacted on a regular basis. A diverse cast of characters lived in the waters here, including large and small temnospondyl amphibians, fish that look alien and fish that look familiar, long-necked tanystropheids, croc-mimic phytosaurs, and aquatic reptiles of uncertain affinity.

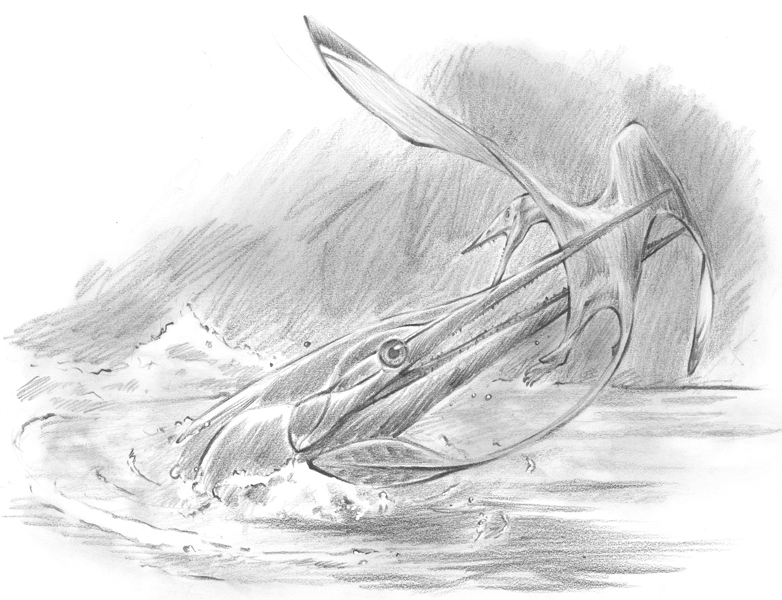

Above: The meter-long, pointy-nosed predatory fish, Saurichthys, attacking a basal pterosaur. Though no pterosaur remains are known yet from Chinle, the nearby Nugget Sandstone Formation of Utah has produced Caelestiventus, so it’s not a big stretch to guess there may have been pterosaurs at Chinle too. Digestive contents from a fossil Saurichthys were once thought to be pterosaur remains, inspiring lots of paleoart like this, but are now identified as those of a tanystropheid.

Above: The very primitive “unicorn” shark, Xenacanthus. These guys appeared way back in the Devonian and survived until the end of the Triassic. I think it’s pretty cool when ancient lineages and more derived ones exist side by side.

Phytosaurs were an offshoot of archosaurs more basal than stem-crocodylians and stem-birds. That is, they were not crocs–crocs and birds are more closely related to each other than either is to phytosaurs–but they converged on a very similar body plan to that of modern crocs. One way to tell the difference is that phytosaurs had their nostrils way up by their eyes, while crocs’ nostrils are on the tip of the snout. Depicted above is the huge phytosaur Smilosuchus and a herd of the huge dicynodont Placerias (more on them later). Smilosuchus was one of the largest known phytosaurs, possibly rivaling some of the largest crocs to ever live, though it’s hard to estimate since it’s only known from skull material. It appears to be approximately Sarcosuchus-sized: 10 meters long and weighing 4 tonnes.

Large temnospondyl amphibians, like the 2-meter Koskinonodon (sometimes known as Anaschisma) above, were another group of ambush predators in Chinle’s waters. This is another very ancient lineage that enjoyed its heyday much earlier in the Carboniferous and Permian, but some stragglers kept holding on until the end of the Cretaceous.

Above: the heavily armored small aquatic archosauriform, Vancleavea. This was a sort of eel-shaped reptile with small arms and legs that would probably not have supported its weight out of the water. Its tail had a fin on it made of osteoderms, a strategy not seen in any other animal (usually swimmy tails are formed from elongated vertebrae). Strange aquatic reptiles like this were common in the Early and Middle Triassic, but by the Late Triassic the ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians started to dominate the waters.

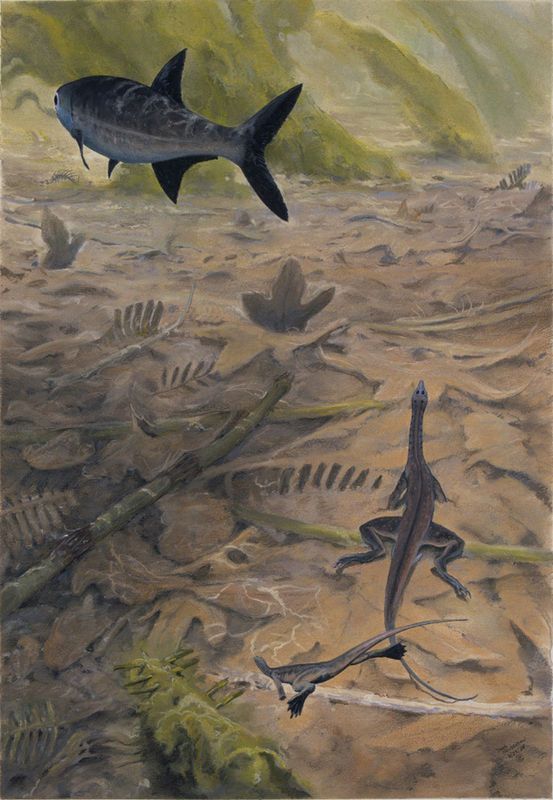

Above: the little long-necked archosaur, Tanytrachelos, swimming frog-like near the small ray-finned fish Turseodus. Tanytrachelos was a smaller, shorter-necked, leggier relative of the more famous Tanystropheus.

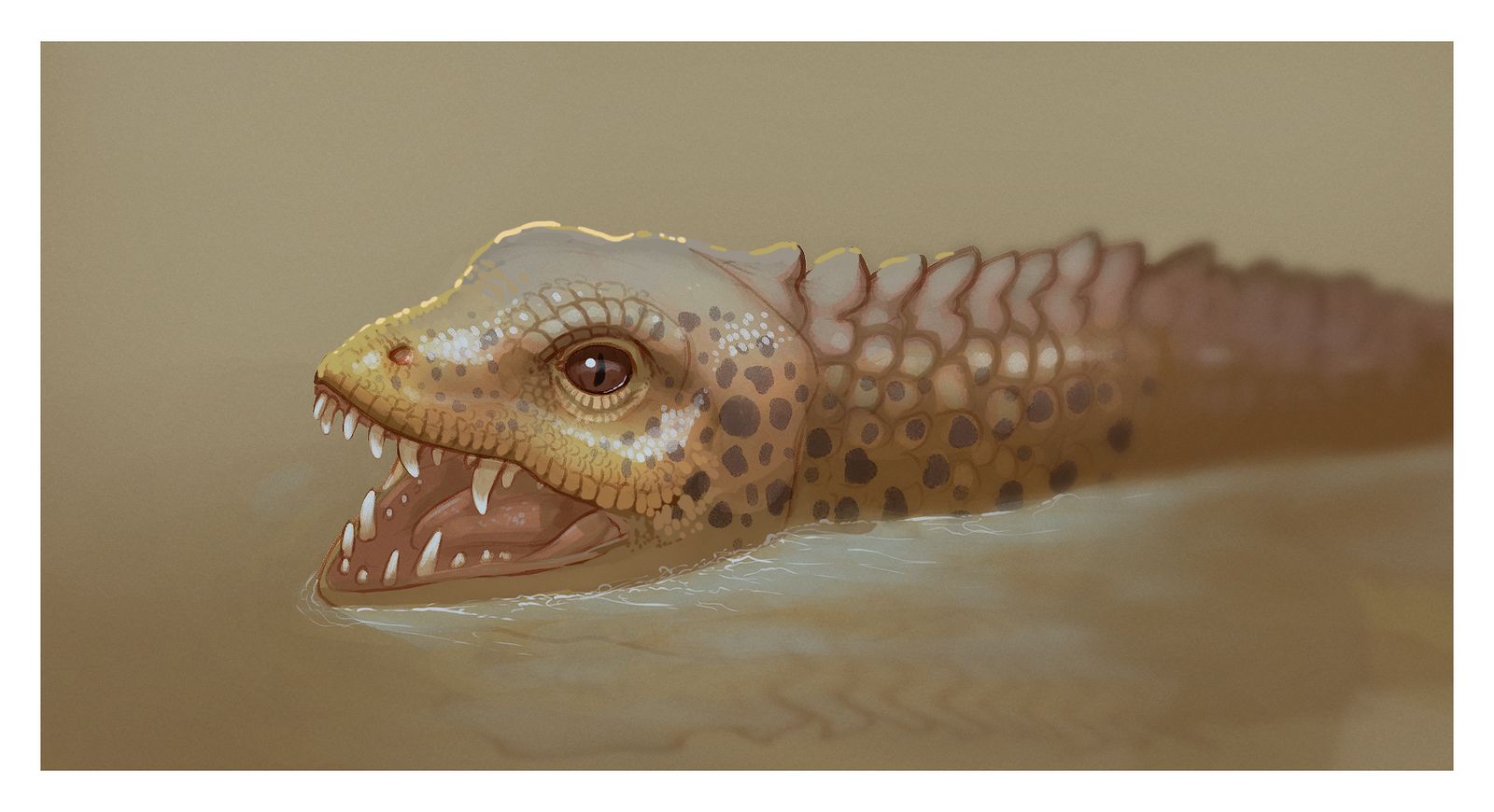

Chinle was also home to the small, semi-aquatic archosauromorph Rugarhynchos, a heavily armored, long-snouted, otter-sized predator closely related to the more well-known Doswellia (pictured; I couldn’t find any good images of Rugarhynchos, but it’s so closely related to Doswellia that it probably looked almost exactly like this). This one has some speculative fluff.

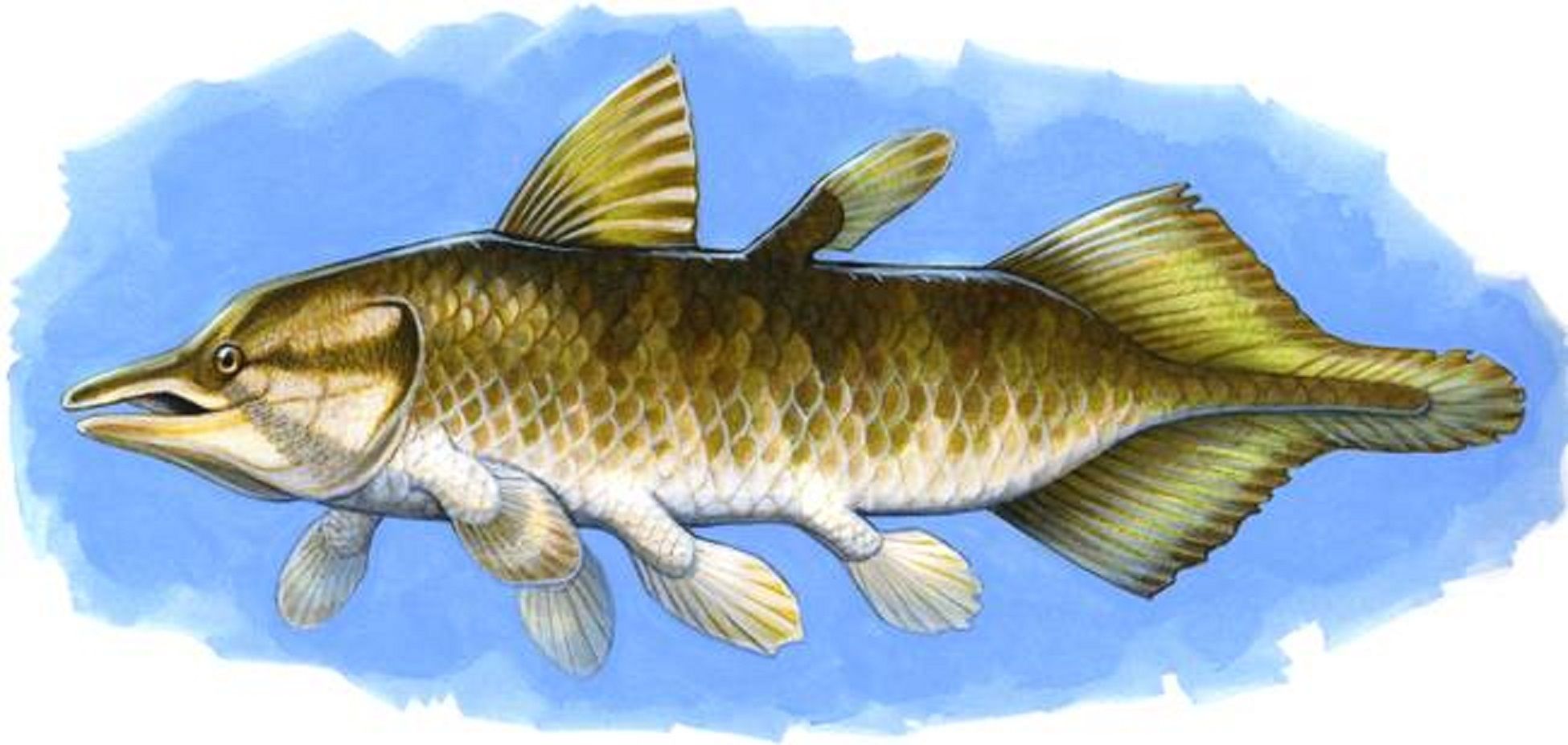

Above: the recognizable coelacanth, Chinlea. Coelacanths have been around since the Devonian, and similar forms to this are still alive today. (That doesn’t mean they’re “living fossils” or “haven’t evolved” though. They just look outwardly similar to their ancestral cousins.)

And before we completely leave the water, here’s the brand-new putative caecilian ancestor, Chinlestegophis. Caecilians are elusive little amphibians that look a lot like earthworms, whose relationship with frogs and salamanders has been under debate for ages. This new fossil from Chinle shares features with both stereospondyls, an ancient amphibian group thought to have no descendents, and caecilians, suggesting that maybe caecilians are actually surviving stereospondyls, which would put them very far away from frogs and salamanders on the tree of life. Read more about that discovery here!

Life In The Trees

Arboreal (tree-dwelling) animals are less likely to fossilize than terrestrial or aquatic animals, so we often don’t have a good idea of the community of animals that lived in the canopy of a paleoenvironment. However, there are a few animals known from Chinle from this habitat, including the most famous and well-studied of the drepanosaurs.

Above: Drepanosaurus was a very specialized reptile reminiscent of a chameleon. It had a robust hooked claw on its second finger that it may have used for digging burrowing insects out of wood, and a “claw” made of fused vertebrae at the end of its tail, presumably for gripping branches. It also had a strange humped back that may have anchored powerful neck muscles, allowing it to shoot its head out quickly to nab insects. Drepanosaurus was one of a family of drepanosaurids, many of which are also known from Chinle, including Avicranium, Ancistronychus, and Dolabrosaurus.

Above: Avicranium (meaning “bird head,” due to the beaklike shape of drepanosaur snouts) is watched by Daemonosaurus (more on that later). While Drepanosaurus and Ancistronychus had enlarged second fingers, Avicranium and Dolabrosaurus did not, indicating maybe they ate something different. Niche partitioning!

Some drepanosaurs took a totally different route: Skybalonyx, above, used a huge spade-like second claw to dig burrows. Drepanosaurs were a very diverse group of animals that only lived in the Triassic, and were totally unlike anything alive today.

Above: This is Trilophosaurus, a dog-sized allokotosaur that may have been arboreal. Although this animal looks lizard-like, we know its close relative, Azendohsaurus, was warm-blooded, so Trilophosaurus probably was too. It had a beak for cropping vegetation and specialized teeth in back for further chopping.

Life On The Ground: Herbivores

As in my Yixian Formation post, I’ll start with the heavyweights and move down the weight classes for both the herbivores and carnivores.

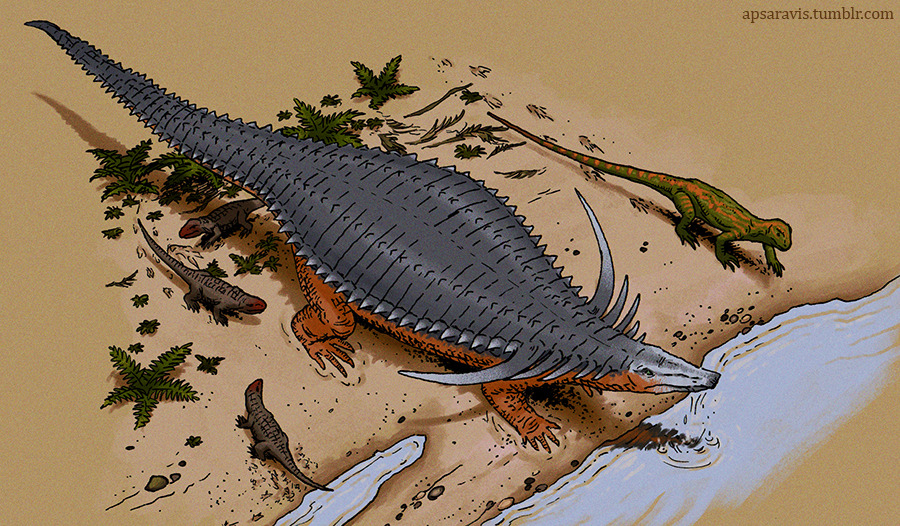

Chinle is the best place in the world to study aëtosaurs, the armored, herbivorous croc relatives that rose and fell during the Triassic Period. These filled the same niche that ankylosaurs (club-tailed dinosaurs) and glyptodonts (car-sized armadillos) would later: low-slung, tank-like large herbiore. Aëtosaurs often had shovel-like snouts, possibly for digging up tubers, mushrooms, and soft plants, sort of like a boar (but less so, since aëtosaurs didn’t have the fleshy, muscular, dextrous face that we mammals do). One of the largest and most famous was Desmatosuchus (above), which could reach lengths of 5 meters and could weigh half a tonne. Its fossils are often found in what looks like family groups, indicating that they were herd animals, also similar to modern boars. It’s also the inspiration for the Pokémon Avalugg!

The other animals in this image are Trilophosaurus again (above Desmatosuchus), and a few Revueltosaurus who we will meet later.

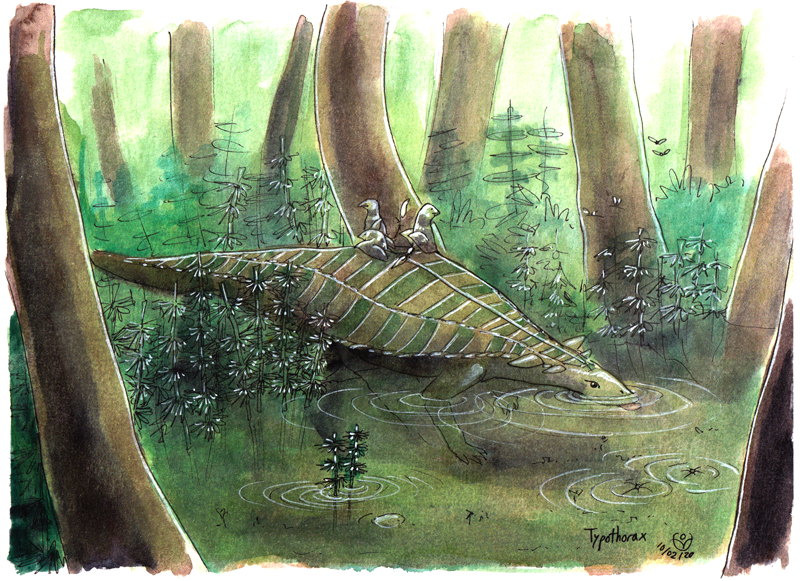

Above: Aëtosaurs also came in smaller sizes, like the 2-meter Typothorax.

Chinle was also home to one of the largest dicynodonts (a type of primitive mammal relative) to ever live, Placerias, which could weigh up to a tonne (this is the same animal as was in the background of the Smilosuchus picture earlier). They were warm-blooded, toothless except for their large tusks, beaked herbivores that probably lived similarly to modern hippos, spending most of their time in shallow water. Dicynodonts arose during the Permian and survived the Great Dying, only to go extinct at the end of the Triassic Period.

The welterweight class of herbivores included the enigmatic, dinosaur-mimicking croc-relatives, Effigia and Shuvosaurus. The holotype skeleton of Effigia (above) was mistaken for that of Coelophysis for decades before anyone realized it wasn’t a dinosaur. These animals were small, swift, bipedal, beaked, and warm-blooded (and thus possibly fluffy).

On the other hand, they may have been scaly and osteodermed like a classic pseudosuchian (stem-croc), as in the depiction of Shuvosaurus above. Either way, their body plan is uncannily similar to certain dinosaurs, especially ornithomimids and modern ratites (emus, ostriches, and kin). A great example of convergent evolution!

Another group of welterweight herbivores, or possibly omnivores, were the silesaurids, close relatives of dinosaurs, represented at Chinle by Eucoelophysis (no relation to Coelophysis). Silesaurids were quadrupedal and lightly built, and may have had beaks; this one is being attacked by a large phytosaur.

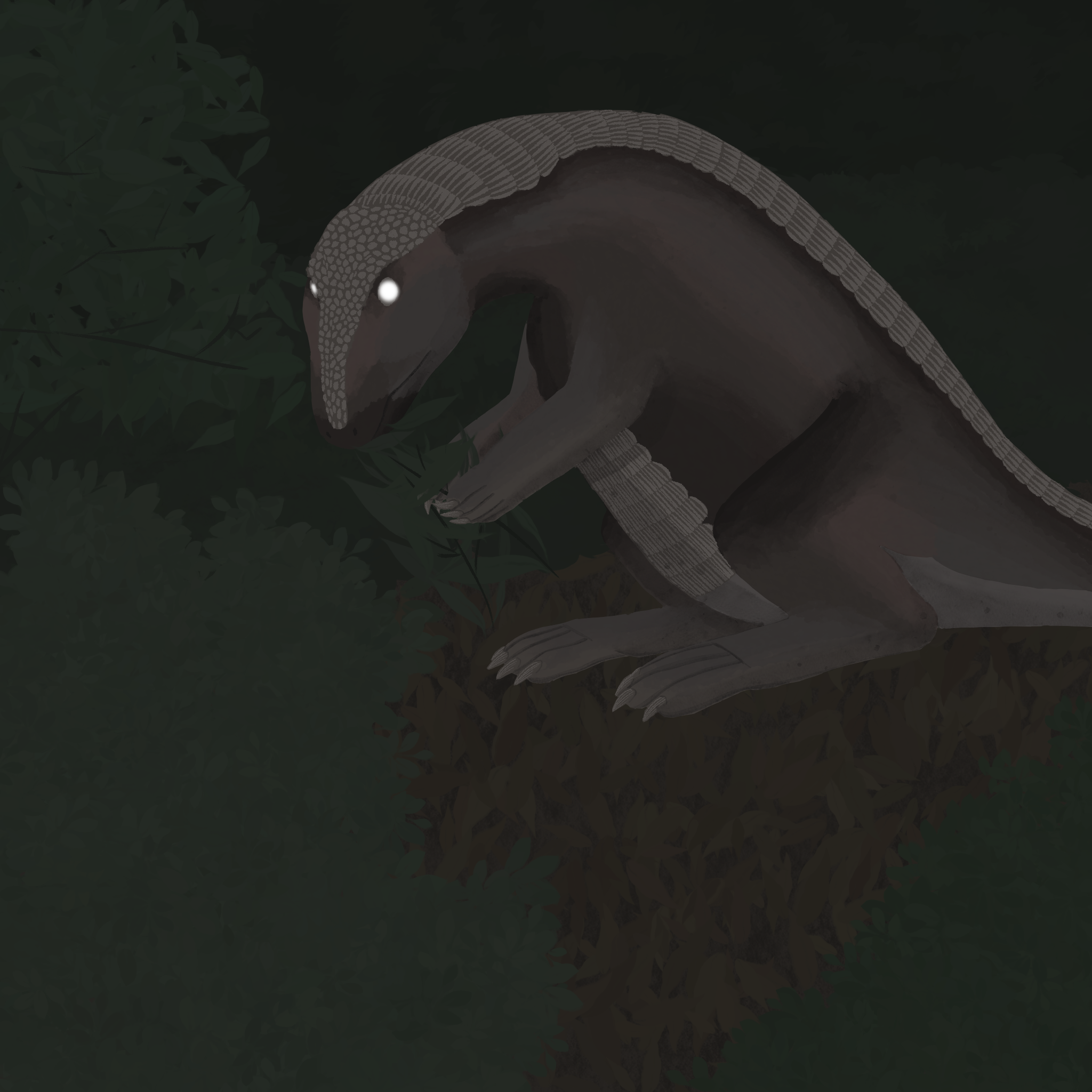

The lightweight herbivores at Chinle included the thin-shelled turtle Chinlechelys, the tuatara relative Whitakersaurus, and the basal croc relative Revueltosaurus (above). Revueltosaurus was a small, basal relative of the larger, more heavily armored aëtosaurs discussed above. To me, it looks a lot like the Crystal Palace Iguanodon in miniature! For this piece I imagined Revueltosaurus as the opossum of Chinle: a medium-sized, bulky, nocturnal generalist, which eats mainly plants but wouldn’t pass up an opportunity to scavenge from a carcass or nab an insect. There’s no evidence one way or the other for a nocturnal or diurnal habit; I just picked nocturnal because I haven’t done many night pieces.

Tuatara are the only living members of Rhynchocephalia, a group whose lineage split off from that of lizards way back in the Early or Middle Triassic. Because they’re so distantly related to any other living animal, they’re commonly called “living fossils” or “basically dinosaurs,” but both these terms are super problematic. Especially the latter: we have dinosaurs around today–birds–and tuatara are not even close to dinosaurs on the tree of life. Check out the Common Descent Podcast’s epidosde on “living fossils” to learn more about the history, meaning, and contention around the use of that term.

Life On The Ground: Carnivores

The apex predator of the Late Carnian was Postosuchus, a large (300 kg) bipedal pseudosuchian that to me looks like someone put a theropod head on a croc body. This animal was one of the stars of the aforementioned Walking With Dinosaurs pilot episode, although they depicted it as quadrupedal (which was a reasonable decision given what they knew at the time).

Terrestrial pseudosuchian apex predators seem to be a thing that happens after really bad mass extinctions. They were common in the Triassic (e.g. Saurosuchus, Fasolasuchus), which followed the Great Dying, the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history, and they made another appearance in the early Paleogene (e.g. Boverisuchus, Sebecus), after the K-Pg extinction, which killed the dinosaurs. Check out this fun TierZoo video for more about croc diversity over time.

You may have noticed that we’re almost all the way through this post, and we still haven’t seen any dinosaurs! Well, look no further. In the Triassic, dinosaurs were not very diverse, and only filled a handful of medium-sized predator niches. The only dinosaurs that existed at this time were theropods (the bipedal, carnivorous ones)–sauropodomorphs and ornithischians would only show up later in the Triassic.

The most famous and well-studied of the dinosaurs from Chinle is the skinny Coelophysis, which is known from thousands of specimens. It’s the state fossil of New Mexico. For some reason it’s become a paleoart meme to draw Coelophysis with a blue face–there’s no evidence for this.

Above: Chindesaurus was around the same size as Coelophysis, but a tad shorter in length and more robust, and may have been a herrerasaurid (a relative of larger, more primitive dinosaurs common in South America).

Above: Daemonosaurus was a bit smaller than Coelophysis and Chindesaurus, and had an unusual short face, perhaps indicating a different feeding style (more niche partitioning!). Its relationship with other dinosaurs is uncertain. This is the same animal that was depicted eyeing the drepanosaur Avicranium above.

By the way, these last three pictures are by the artist Dinostavros on Deviantart. They only draw Triassic dinosauromorphs. That’s some highly specialized paleoart!

In the lightweight carnivore category, Chinle had a few clades represented. Hesperosuchus (above) was a cat-sized crocodylian, here depicted with a speculative coat of fluff. This is essentially the body plan that inspired my Velosuchus triathlon critter!

Above: Dromomeron was a rat-sized lagerpetid (close relative of dinosaurs and pterosaurs) that would have been carnivorous or insectivorous. During the Late Triassic, the line between dinosaurs and non-dinosaurs was very blurry; true dinosaurs, lagerpetids, silesaurids, and other dinosauromorphs all lived side by side.

Last but not least, we have the hamster-sized, brand-new cynodont (mammal relative), Kataigidodon, which was probably omnivorous.

In addition to all the taxa I’ve listed here, there’s a ton of unidentified or tooth-only material known from Chinle, some of which are so weird that we can’t even tell whether the tooth owner was a mammal or reptile. Some interesting examples include teeth from the oldest known venomous reptile, Uatchitodon; teeth named Kraterokheirodon that can only be identified as probably an amniote; and partial skulls named Acallosuchus and Palacrodon that can only be identified as probably reptiles. Hopefully, as research continues, we can uncover more fossils and match them up to what we already have, and solve the mysteries! I think it’s pretty cool that even though paleontology is the study of things long dead, we’re always moving forward and learning new things.

Conclusion

The Triassic is one of my favorite geologic periods, since it had such an interesting, diverse mix of animals representing a variety of lineages, with no clear dominating group, unlike the earlier Permian (in which the synapsids (stem-mammals) were the most diverse and abundant), the later Jurassic and Cretaceous (in which the dinosaurs ruled), and the Cenozoic (the Age of Mammals). In the Triassic, it was still anyone’s game as to who would go on to inherit the Earth. I hope you have a better picture of what the flora and fauna of the Chinle Formation looked like, and I hope this post helps put some of the more famous members like Coelophysis and Drepanosaurus in ecological context. Thanks for reading!

Image Credits:

Saurichthys Xenacanthus Smilosuchus Koskinonodon Vancleavea Tanytrachelos Doswellia Chinlea Chinlestegophis Drepanosaurus Avicranium Skybalonyx Trilophosaurus Desmatosuchus Typothorax Placerias Effigia Shuvosaurus Eucoelophysis Postosuchus Coelophysis Chindesaurus Daemonosaurus Kataigidodon Hesperosuchus Dromomeron