Over the earth’s history, the skill “Powered Flight” has been unlocked at least four times by four different groups:

- Insects, 350 million years ago in the Carboniferous

- Pterosaurs, 228 million years ago in the Triassic

- Birds and friends (paravians), 160 million years ago in the Jurassic

- Bats, 60 million years ago in the Paleogene

Each of these groups took to the air using a different strategy. In this post, we’ll compare the physiology of the wing surfaces between groups, discuss a little bit about their evolution, and examine the pros and cons of each. They’re quite different from one another!

Overview

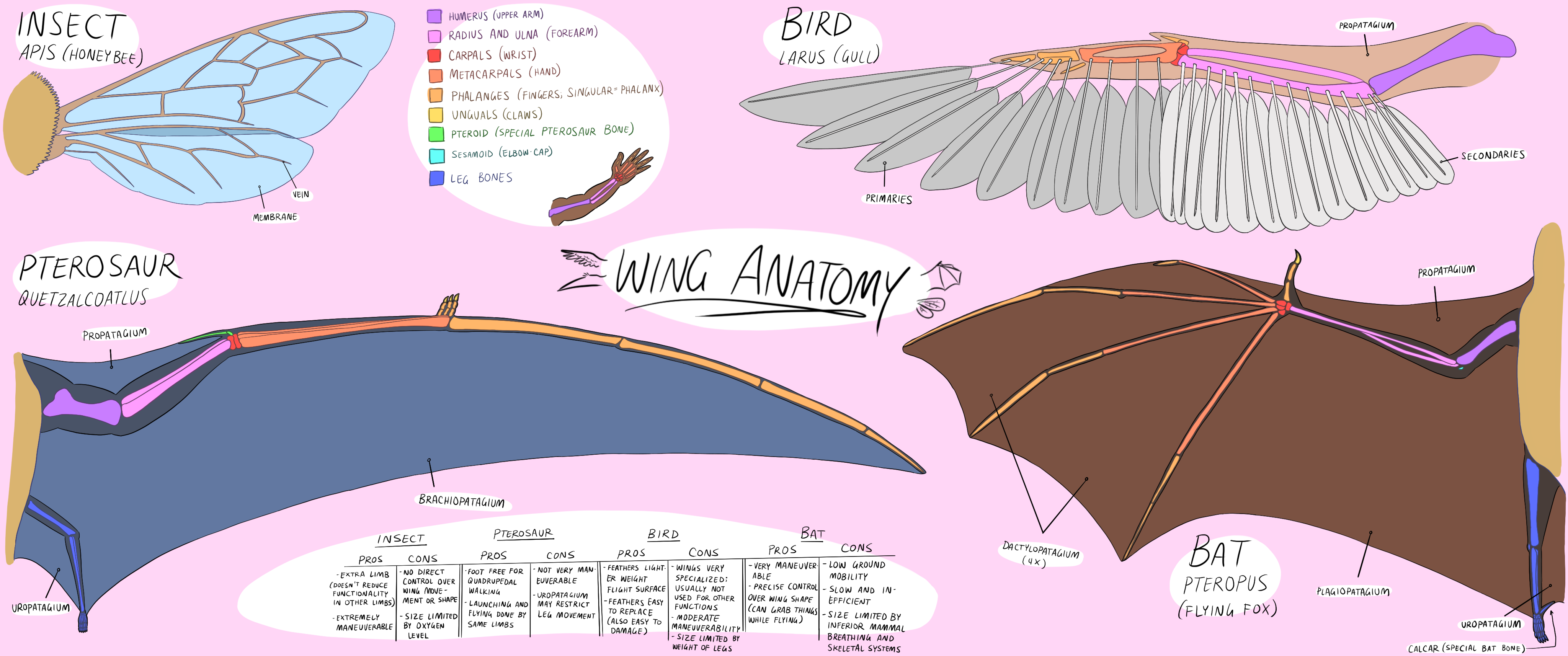

Here’s a quick infographic comparing the homologous structures (corresponding bones) of the different wing types.

It looks like a lot of information, but I’ll zoom in on each wing type later in this post. But first, let’s cover some shared terminology.

A patagium is a stretchy membrane of skin connecting two parts of the body that are somewhat mobile relative to each other. Each patagium is has a prefix that reflects its position or the body parts it’s connecting: a bat’s dactylopatagium connects two fingers (“dactylo” meaning “finger”), a pterosaur’s brachiopatagium connects its arm to its body (“brachio” meaning “arm), etc. For some animals, like pterosaurs and bats, the patagia form the entire flight surface, while in birds, the propatagium, which connects the wrist and shoulder (“pro” meaning “before”), is important for aerodynamics but does not make up a large flight surface. The gliding flaps on animals like colugos (flying lemurs), sugar gliders, and flying squirrels are also called patagia.

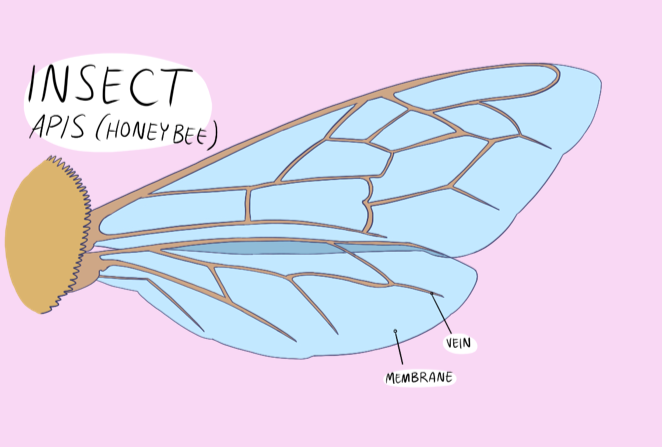

Insects

Insects were the first organisms, by a long shot, to achieve powered flight. For over a hundred million years, they were the sole occupants of Earth’s skies. They were beginning to evolve flight at around the same time early tetrapods were beginning to come onto land.

In addition to being the first fliers, they are also the most diverse, as well as the most accomplished. There are an estimated 10 million species of living things on Earth, and about one million–one in every ten living things–are just beetles. Entomologists only half-joke that you could go into any rainforest, shake any tree, and identify a hundred new beetle species. Not only are flying insects ridiculously abundant and diverse, but they are the norm–nearly every insect is capable of flight at some point in its life. And man, are they acrobatic–we take it for granted that flies can land upside-down on the ceiling, but can you imagine a helicopter or even a drone pilot doing that?

The mechanics of an insect wing are different than that of a vertebrate wing in a number of ways. First, the wing isn’t an exapted limb. Flying vertebrates give up some functionality of their forelimbs by converting them into wings (for example, a bird can’t manipulate objects with its arms like a monkey or squirrel). Insects have all their legs, plus wings. It’s unknown what the wings evolved from–the leading theories are that they came from gills, nubs on the thorax, or proto-legs. Second, an insect’s wing is a rigid structure. The insect can’t change the shape of its wing except what happens indirectly through forces exerted by the air during flight.

There are two styles of insect wing musculature: direct and indirect. Dragonflies, mayflies, and other paleopterans employ direct control, in which each wing has a muscle attached at the base that controls that wing–the way you’d expect it to work. However, neopterans (which includes a majority of insects) often need to flap their wings faster than the frame rate of nerves. (This is how things that seem really un-aerodynamic like junebugs or jewel beetles can still take to the air.) To achieve this, they are able to vibrate their bodies really fast, which moves their wings, but means that they don’t have control over each individual flap; it’s more like an on/off switch. Imagine breathing in and out really fast–faster than you can even think–and that also moves your arms up and down. That is how the neopteran do.

The biggest insects ever to fly were griffinflies like Meganeura, which lived in the Carboniferous and Permian periods (323-252 million years ago), and resembled dragonflies the size of a crow. However, being thin and lightweight, they probably were comparable in mass to modern Goliath beetles, which also are flight-capable.

Arthropods (the family of armored critters that includes insects, crustaceans, arachnids, and their relatives) in general are limited in size by the level of oxygen in the atmosphere. They breathe mostly passively, through diffusion, which means that if there’s a higher oxygen partial pressure, oxygen can penetrate deeper into their bodies. While the world hasn’t yet seen a flying insect limited by the oxygen level–griffinflies didn’t even come close to the size of the largest arthropods, the 2.5-meter millipede Arthropleura and the 2.5-meter sea scorpion Jaekelopterus, instead being limited in size by some other factor like prey availability or aerodynamics–a theoretical maximally-sized flying insect still wouldn’t come close to the sizes achieved by flying vertebrates.

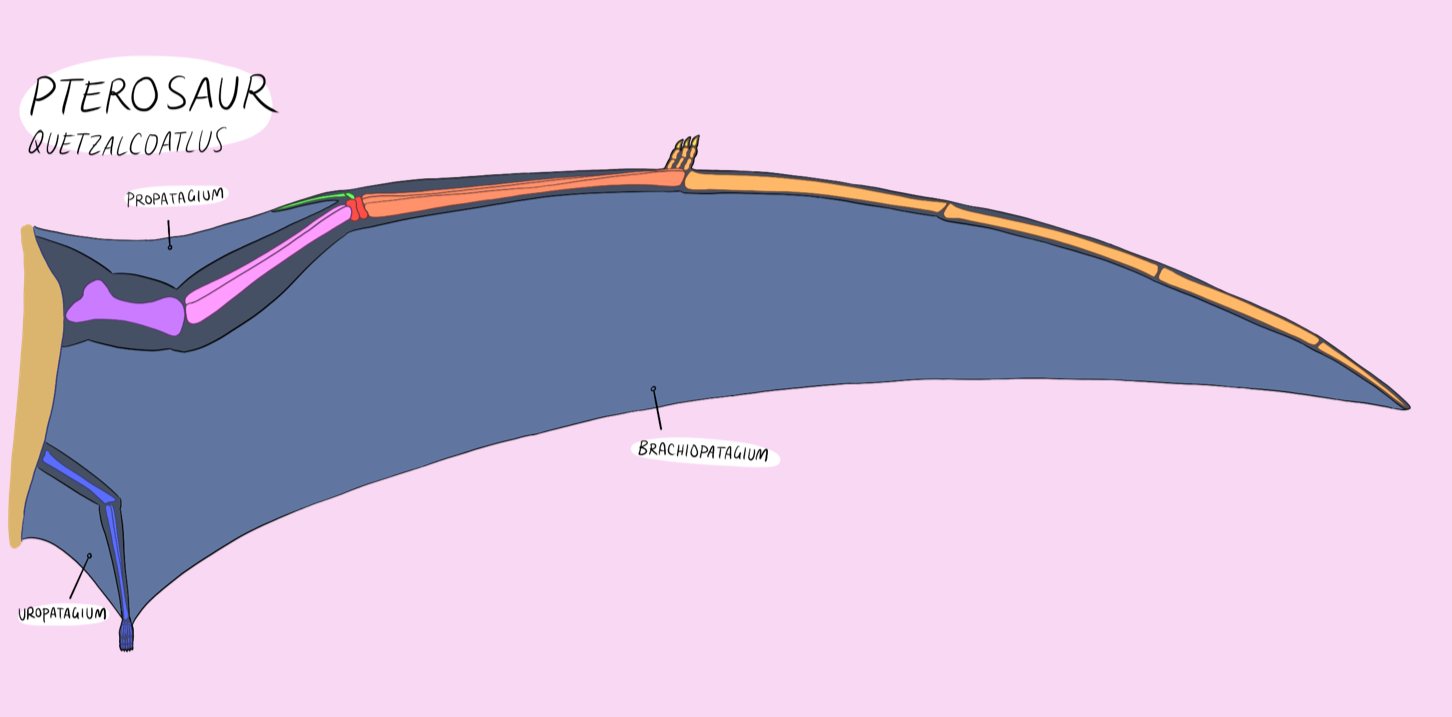

Pterosaurs

The first vertebrates to take to the skies were the pterosaurs, which are not dinosaurs but are close relatives of dinosaurs that showed up rather suddenly in the Late Triassic, around 228 million years ago. See my pterosaur family overview for more details about pterosaur evolution and specific clades.

A pterosaur’s wing consists of the arm, an elongated hand (which a lot of popular art and movies fail to depict), a little three-fingered foot, and a ridiculously robust and elongated fourth finger. They also have a little extra bone called the pteroid that supports the propatagium, which is unique to pterosaurs. To better picture how a pterosaur wing is homologous to your hand, stick out your thumb, index, and middle fingers and then put the ball of your hand on the ground. Imagine your ring finger stretches backward and upward a great distance, and your pinkie is missing. That is how the pterosaur do.

Note that many early pterosaurs from the Triassic Period had hands that were less elongated, and at the very end of the Cretaceous Period, some pterosaurs like Nyctosaurus actually lost their non-wing fingers entirely, and reduced the wing finger down to three phalanges. So this anatomical diagram isn’t one-size-fits-all.

The unique thing about pterosaurs compared to almost all other flying animals is that they were quadrupedal: their folded wings could act as another pair of weight-bearing legs. This would’ve made them potentially quite agile on the ground, and it’s hypothesized that many pterosaurs were mainly terrestrial stalkers, hunting prey on the ground rather than on the wing.

Above: the small, toothy early pterosaur Dimorphodon, by Mark Witton.

In addition to effective ground locomotion, having feet on their wings provided pterosaurs with another interesting advantage: quadrupedal launching. Birds take off by jumping using their hind limbs, then flapping with their front limbs, meaning both sets of limbs must be strong. And when birds fly, those strong legs are mostly just ballast. Pterosaurs were able to pole-vault over their front limbs to take off (if you can’t visualize that, here’s a great video), which allowed them to reduce their legs into little toothpicks and concentrate all their muscle mass into their arms. This is what allowed the largest pterosaurs, the azhdarchids of the Latest Cretaceous like Quetzalcoatlus, Hatzegopteryx, and Arambourgiania, to reach airplane-like sizes of up to 250kg with a wingspan of 11 meters. 10/10, would ride into battle.

Important note: There’s a crackpot pseudoscientist out there named Dave Peters who runs two websites, Reptile Evolution and The Pterosaur Heresies. He makes a lot of content, including some very scientific-looking skeletal diagrams that come up when you google various pterosaur and archosaur genera. Don’t believe him! All his pet theories are totally unsupported by actual science, and many of his skeletal diagrams are extremely misleading and outright wrong. Check your source if you’re researching pterosaurs, and avoid Dave Peters’s websites!

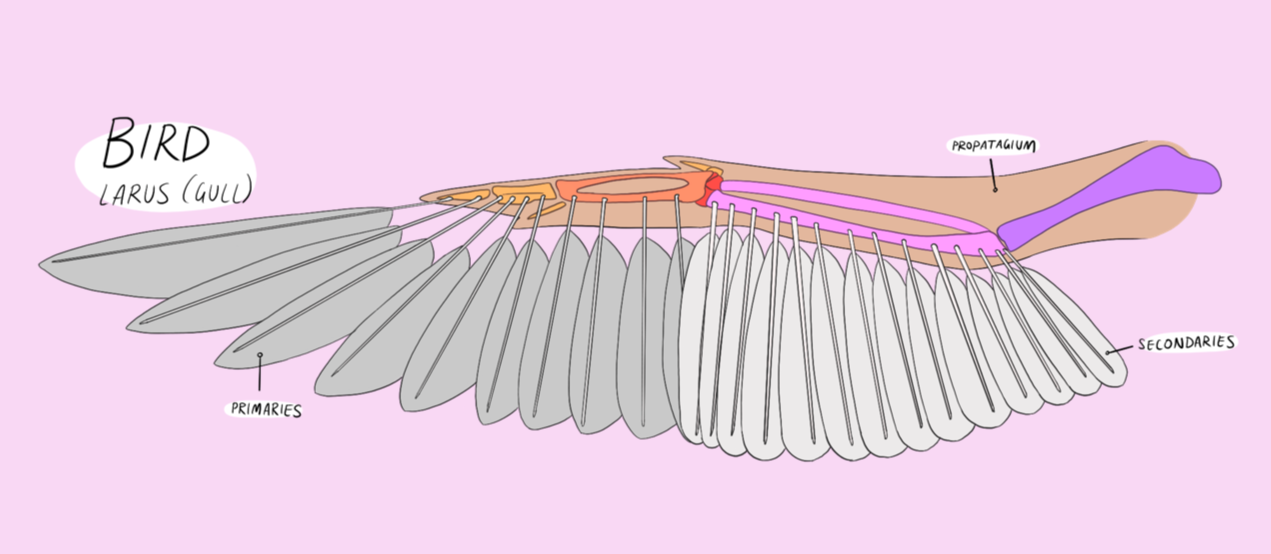

Birds

Birds and their close relatives were the second group of vertebrates to achieve powered flight, sometime during the Late Jurassic, around 160 million years ago. Bird ancestors evolved complex feathers for purposes other than flight first–probably for display, and later for wing-assisted incline running and even later, for gliding or parachuting–and only later became capable of powered flight. This is evidenced by some of the earliest recognized birds, Serikornis, Aurornis, Anchiornis, and others, which were flightless but very feathery and otherwise birdlike. The famous Archaeopteryx, which lived ten million years later, probably could, but lacking a keel (wishbone), it would’ve flapped differently than modern birds do, and would not have been a very good flier.

Above: Archaeopteryx, the first known bird capable of powered flight, by Emily Willoughby. According to melanosome analysis of a single isolated feather, we think that at least one of its wing feathers was black.

While it’s hard to even know if this is a meaningful question to ask due to the blurriness of the line between non-avian and avian dinosaurs, it’s probable that flight was gained and lost many, many times among early bird relatives. Another relatively well-known group of “raptor” dinosaurs, the four-winged microraptorines, including the famous Microraptor, probably achieved powered flight independently, using a different strategy than either Archaeopteryx or modern birds. (And, unlike Archaeopteryx and the earlier anchiornithids, microraptorines definitely fell outside of birds on the tree of life.) This group had a birdlike wishbone, but lacked the shoulder flexibility required for a full flapping stroke, and had asymmetrical flight feathers on their legs as well, making their flight postures and movements hard to imagine from a modern perspective.

The wings of birds and their relatives consist of the arm and a robust, three-fingered hand, which is capable of folding flat against the forearm thanks to a special half-moon-shaped wrist bone called the semilunate carpal. To imagine this, stick your hand out like you’re about to shake someone’s hand. Now, without rotating your arm, try to point your fingers toward the floor. Humans can only achieve a measly obtuse angle, but birds can touch their fingers to their forearms this way, which is how they fold their wings. Also imagine that you can clap the backs of your hands together behind your back with your arms straight. That is how the bird do.

Note: When you eat chicken wings, people often refer to the pieces as “drums” and “flats”. The “drum” is actually the upper arm (the bone inside is the humerus), and the “flat” is the forearm, containing the radius and ulna.

While birds are the dominant flying vertebrates today, their flight strategy has some drawbacks. For one, their wings are very specialized instruments for flying, and aren’t very good at doing anything else. Some birds use their wings for swimming, and others for balance while running, but in general, when not flying, the wings are just tucked out of the way. Also, while more maneuverable than similarly-sized pterosaurs, birds (with the exception of hummingbirds) can mostly just fly forward, and at large sizes have trouble taking off and landing gracefully. And as discussed above, birds’ method of launching using one set of limbs and then flying with the other limits them to a smaller maximum size than pterosaurs, who could concentrate all their muscle mass into one set of limbs. The largest flying birds ever to live were Pelagornis, a huge pseudotoothed albatross-like seabird that lived during much of the Cenozoic, which had a wingspan of up to 7.4 meters and could weigh up to 40 kilograms; and Argentavis, a giant vulture relative from the Miocene that had a shorter wingspan of 6.5 meters but was much heavier, tipping the scales at up to 72 kilograms. That’s very big–heavier than an average person–but it’s only a sixth of the size of the biggest pterosaurs.

Both birds and pterosaurs had super-efficient one-way breathing systems made up of auxiliary air sacs that keep the old air from mixing with the new. The air sacs also penetrate the bones, allowing those creatures to concentrate their bones’ mass in the places that need the most strength. Bird bones aren’t necessarily lighter than an equivalently sized mammal bone, but their mass is distributed more efficiently!

Among flying animals, birds are also unusual in the number of times they’ve given up flight. Penguins, giant cormorants, rheas, ostriches, kakapos, Hesperornis, phorusrhacids (terror birds) and many others all became flightless independently. Why? Flight is very costly in terms of energy and body specialization, so if you don’t need it, it makes sense not to invest that cost. However, it’s possible that bats and pterosaurs’ body plans were too specialized to do anything else, while birds’ strong dinosaur legs, while holding them back from truly huge flying sizes, allow them to become powerful runners, swimmers, and climbers when the conditions are right. For insects, flight doesn’t seem to be as costly as it is for vertebrates, so losing flight doesn’t convey much of an advantage. Plus, being tiny, a flying insect can inhabit an area many orders of magnitude bigger than a flightless one, which would have to crawl up and down a million dead leaves to traverse a forest, making flight even more important to their lifestyle than vertebrates.

Bats

The last animals to figure out how to fly* were the bats, which appeared in the Eocene epoch around 53 million years ago. Like pterosaurs, we don’t have a good record of how bats made the transition to flying; the oldest known bat fossils like Onychonycteris look pretty much like bats. Bats are an early offshoot of the group Laurasiatheria, which includes dogs, horses, whales, hedgehogs, and their ancestors.

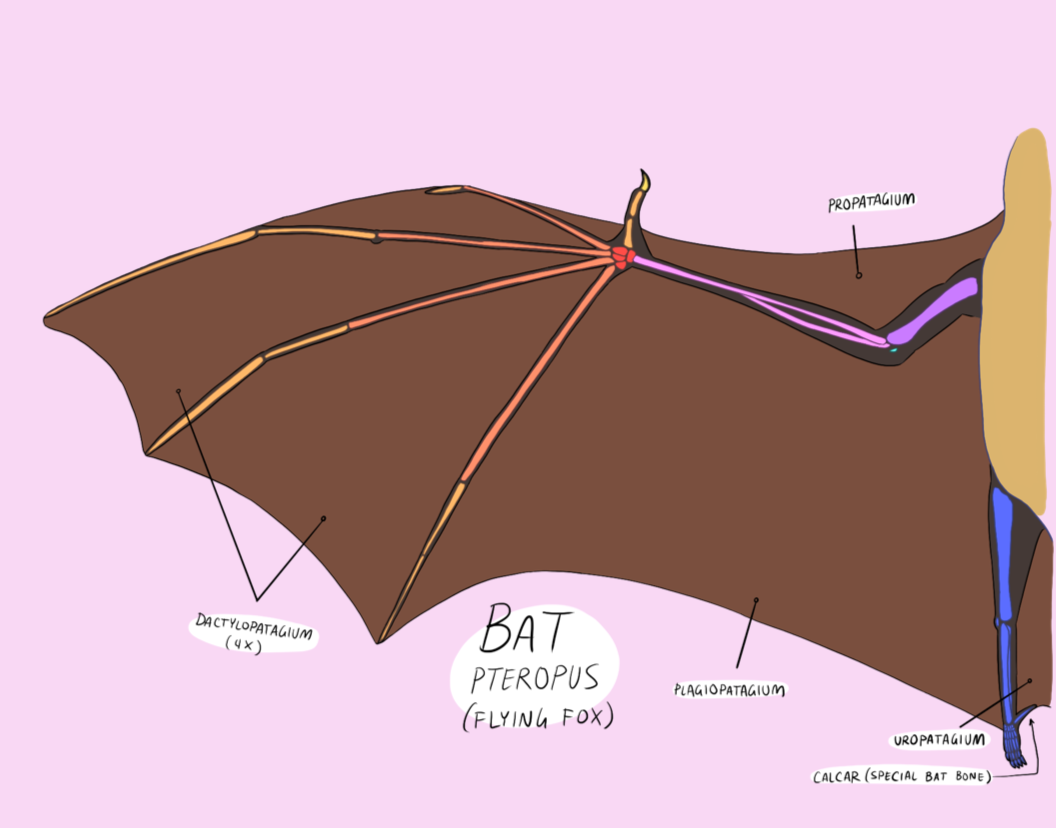

It’s much easier to visualize the homologous structures in a bat’s wing than in a bird’s or pterosaur’s–it’s just a big stretched out hand. And it can make basically any gesture you can make with your hand, giving bats the most precise control over their wing shape of any vertebrates. Many bats and birds are insectivores that catch bugs while flying, but bats do it differently: while birds grab bugs with their beaks, much like you’d expect, bats actually grab bugs with their wing, pass them to their feet, and then pass it again to their mouth. All while flying.

Most bats have totally given up on walking, instead taking off and landing in trees or caves and crawling very, very awkwardly if they end up somewhere else. However, there are a couple bat families that are accomplished walkers, including vampire bats, which hunt on the ground, and New Zealand’s burrowing bats, which seem to be in the process of becoming flightless (classic New Zealand). They are able to fold their wings so tightly that you can’t even tell they’re there, and hop agilely on all fours in a manner possibly reminiscent of small pterosaurs.

Above: the greater New Zealand burrowing bat, Mystacina robusta, which now may be extinct. Art by Gavin Mouldey.

Compared to a similarly-sized bird, a bat is an extremely slow and inefficient flier, but they make up for it by specializing in maneuverability. Bats are by far the most agile vertebrate aerialists, second only to insects among all animals. However, as mammals, they are limited in size due to their inefficient skeletal and breathing systems compared to ornithodirans (dinosaurs and pterosaurs). The largest known bat to ever fly is the golden-crowned flying fox, Acerodon, which has a wingspan of up to 1.7 meters and can weigh a whopping 1.4 kilograms (3 pounds). The Indian flying fox, Pteropus (whose wing I used in the diagram), is slightly heavier at 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds) but with a slightly shorter wingspan of 1.5 meters.

You may have heard that bat meat from a Wuhan wet-market is what kicked off the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. While this hasn’t been unequivocally confirmed, it’s definitely plausible: bats are probably the most dangerous vertebrate group as vectors of disease to humans. The reason for this is related to their flying ability! Since flying is so metabolically expensive, flying animals tend to run hotter than groundlings. While birds’ closest living relatives, crocodiles, are cold-blooded and thus not an apples-to-apples comparison, what we know about non-avian dinosaurs from their bone histology confirms that their metabolism was slower than that of birds but much faster than that of other reptiles. Mammals are similar–a flying bat’s core temperature can soar to 41 degrees Celsius (106 F), which isn’t enough to kill disease-causing viruses and bacteria, but it’s enough to slow their replication enough that the bats themselves don’t get sick (this is what fevers are for). But that means bats are often carriers for all kinds of horrible illnesses, and since they’re more closely related to us than any other hot-blooded flying animals, the diseases bats harbor are more likely to be able to infect us. Bats were also responsible for the ebola outbreak, and they’re agents for the spread of rabies, Hendra and Marburg viruses, histoplasmosis (a fungal infection), and many others as well.

Despite all this, I am a fan of bats. They’re the only mammal representatives to achieve self-powered flight–our only entry in this event of the animal Olympics. Go Team Synapsid!

* Excluding humans

Conclusions and Further Reading

Unpowered flight or gliding has also been achieved by many groups using many different strategies, including but not limited to:

- Rib-winged lizards (Kuehneosaurus, Draco)

- Frisbee snakes (Chrysopelea)

- Parachute mammals (colugos, flying squirrels, sugar gliders)

- Flying fish

- Leg-winged lizards (discussed more below)

- Scansoriopterygid dinosaurs (Yi, Ambopteryx; see my dinosaur family overview)

However, while the advent of powered flight among each of the above-discussed groups resulted in rapid subsequent diversification, this isn’t true when animals learn to glide. While pterosaurs, birds, bats, and insects are each super diverse and successful, gliding animal groups seem to be evolutionary one-offs, no more diverse than their non-gliding counterparts. Read more about it here.

Ever since the little dinosaur Yi and its relatives were discovered to have had dragon-like wings in 2015, there has been debate as to whether or not they were powered fliers. The most recent research suggests emphatically that they weren’t–and they weren’t even very good gliders, either. Read more about it here.

All three groups of flying vertebrates–pterosaurs, birds, and bats–have turned their front limbs into wings. However, that doesn’t have to be the case. One very strange family of Triassic archosauromorphs (relatives of crocs and dinosaurs) with only two known members, called the Sharovipterygidae, used their legs as gliding surfaces:

And here are some speculative, powered-flying descendants of the sharovipterygids, called “sharovipterosaurs”:

I wish these were a thing!

The page image up top is the new little mud-probing pterosaur, Leptostomia, from Early Cretaceous Morocco. It’s the first pterosaur known with shorebird-like adaptations, but it really shouldn’t be surprising that they did something like this. Modern mudflats support a ridiculous diversity of probing birds (see my dinosaur photography post number 3), so it makes sense that pterosaurs would have tried their hand at exploiting that resource. This was originally a photo of a willet catching some kind of invertebrate, which I manipulated in Procreate to be a similarly-colored, similarly-posed pterosaur. I’m pretty happy with how it turned out, and since the background was already given, it didn’t take that long. I’ll probably do more of these in the future.

Thanks for reading! I hope you’ve learned some things you didn’t know about how various animal groups are able to fly. There’s a lot more to it than initially meets the eye. Whose wing design do you think is the best?

Image Credits:

Dimorphodon Archaeopteryx Mystacina Ozimek Sharovipterosaurs