Like a lot of people, I took AP Biology in high school, and memorized a bunch of stuff about the Krebs cycle and the electron transport chain and how mitochondria is…you know what it is. But I realized recently that I didn’t actually have a sense for how metabolism actually worked–what happens to the components of food as you digest them, on a molecular level. So, I did a bunch of research, and present to you a bird’s eye overview of biochemistry.

At a very, very high level, all organisms are very well-organized arrays of chemicals, and everything an organism does is driven by molecular collisions. If you were to somehow shrink yourself down and walk into a cell, you would be immediately pummeled to death by all the particles slamming around. I think it’s a pretty amazing feat to be able to exert such tight control over such chaotic conditions. Go life!

Macros

You’ve probably heard of “macros,” or macronutrients (so called because you need them in large quantities, as opposed to micronutrients like vitamins and metals), in the context of food science: lipids (including fats), carbohydrates, and proteins. These are the three types of molecules whose chemical energy or raw materials organisms can harness to do all the tasks they need to do to survive, including moving around, repairing damage, and reproducing. Basically all organisms, from the lowliest bacterium to plants to humans, share the same methods of breaking down macros, indicating that these chemical processes were one of the first things to arise when life began. The only difference is how the organism obtains said macros–some are eaten or absorbed, and some are synthesized from other materials inside the organism. Plants almost exclusively do the latter, but heterotrophs like animals and fungi don’t just do the former. While a majority of the material their bodies use comes from food, some is produced internally, such as how humans can produce vitamin D (which is a type of fat) in the presence of sunlight.

In modern fad diets, protein is the only “good” macro, with carbohydrates portrayed as “evil” and fat somewhere in between, but this wasn’t always the case. In the mid-twentieth century, fats were vilified, leading to lots of high-sugar products advertised as fat-free and thus healthy. Seems like it’s only a matter of time until proteins take their turn as the bad guy!

There are two other types of biomolecules that are not considered macronutrients: nucleic acids, such as DNA, and alcohols. These can also be metabolized for energy, but are not necessary for life.

Metabolism is the conversion of different types of chemical energy into ATP, which is the “currency” of cells. It’s a small nucleic acid that stores energy in a convenient, easily accessible form. Once created, it can be moved somewhere else and use its stored energy to power cellular functions. The aforementioned Krebs cycle is the series of chemical reactions cells use to make ATP.

Carbohydrates and Lipids

The smallest unit of a carbohydrate is a monosaccharide (meaning “one sugar”), which is made of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen. The most common monosaccharides are glucose, galactose, and fructose, which can be combined a la video game crafting into disaccharides (“two sugars”): glucose + glucose = maltose, glucose + galactose = lactose, glucose + fructose = sucrose. (If it ends in -ose, it’s probably a sugar.) Mono- and disaccharides can be further combined into complex carbohydrates such as starch, cellulose (fibrous plant material), and chitin (eg, crab exoskeletons), which are useful structural elements.

To be metabolized, carbohydrates first have to be broken down into monosaccharides, which can then be further broken down to exploit for energy. Glucose is the easiest monosaccharide to digest–it’s turned into pyruvate, which is an input to the Krebs cycle, which makes ATP. Fructose takes more steps than glucose to become pyruvate, and galactose is converted to glucose.

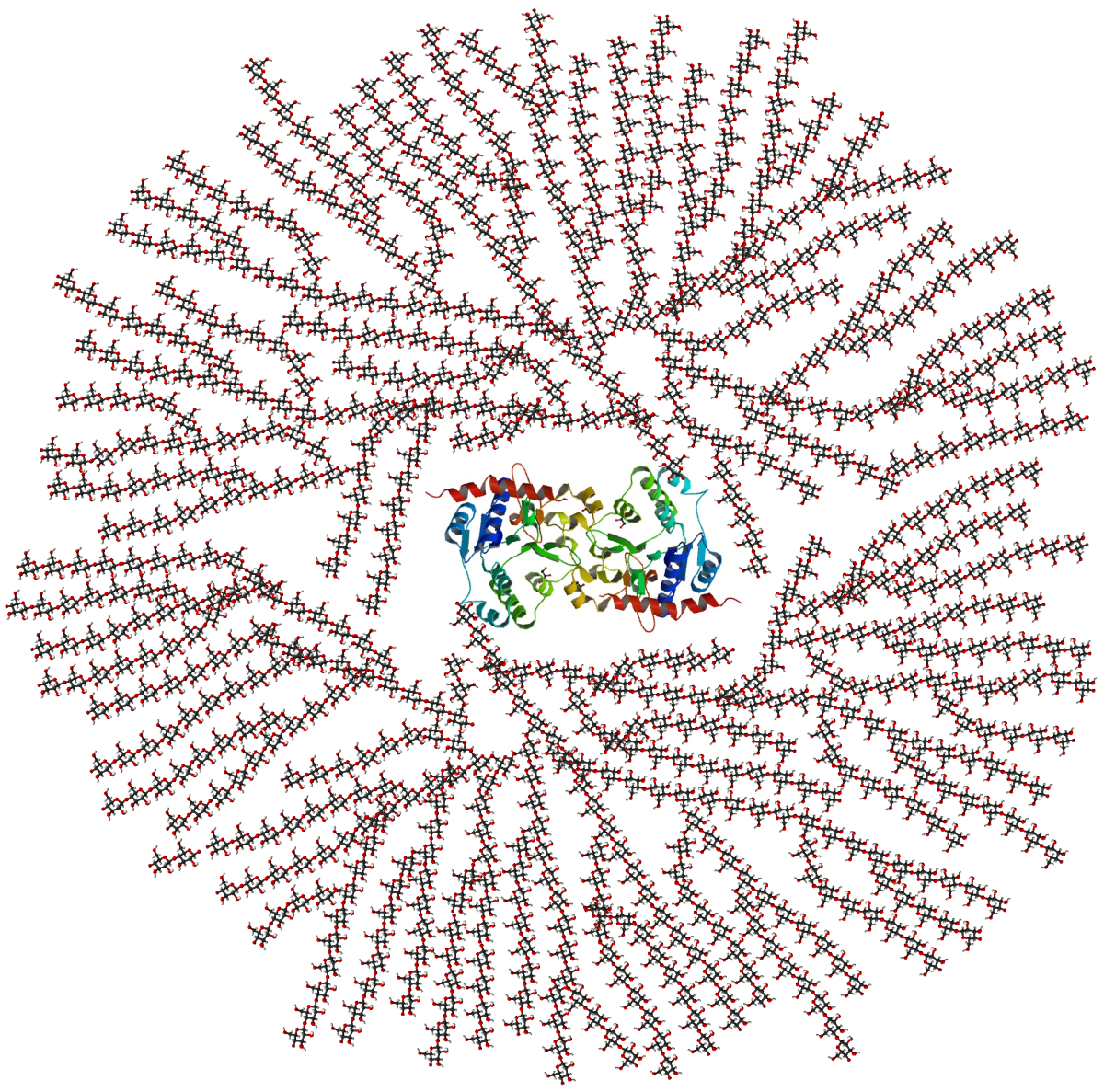

If ATP isn’t needed immediately, glucose can be stored in the form of glycogen, which consists of a mother-duck protein, glycogenin, holding hands with a bajillion glucose, like so:

This keeps the glucose from running away. (It’s more efficient if the agents that digest glucose can do a bunch back to back without having to wander around looking for more glucose.)

And if there’s even too much glycogen, pyruvate can even be turned into lipids and stored as fat. If the energy from the fat is needed later, it can be converted into other substances that can be used as inputs to the Krebs cycle to make ATP (but it can’t be converted back into glucose). In this way, lipids and carbohydrates are similar in how they act on the body.

Lipids are also used for other purposes in cells besides energy storage. Phospholipids make up the membranes of cells, and many hormones are lipids, including estrogen, testosterone, cortisol, and progesterone. (“Hormone” means a molecule used as a signal. Some hormones are proteins, like oxytocin and insulin.) Vitamins A, D, E, and K are also lipids. (“Vitamin” means a substance that can’t be synthesized internally, but is necessary for life. So in humans, D is technically not a vitamin. The B vitamins are proteins, while vitamin C is a carbohydrate.)

Proteins

While carbohydrates and lipids are digested for energy, proteins are digested for their raw materials, known as amino acids, which are then reassembled into other proteins based on the instructions provided by DNA or RNA. They all are mostly composed of oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen, but different amino acids contain small amounts of more exotic elements. Proteins are the main actors and structures in an organism. You probably know that muscles are made of protein, but so are bones (which are fibers of collagen interwoven with the hard mineral hydroxyapatite) and hair, nails, and horns. Enzymes, the actors that cause chemical reactions in cells, are also proteins, as are the “doors” on cell membranes that control what goes in and out.

Only 20 amino acids are coded for in DNA, 19 of which are left-handed. (Many molecules exhibit “handedness,” meaning that they aren’t the same as their mirror image.) Hundreds more amino acids naturally occur outside of organisms just due to inorganic chemical processes, but since proteins require assembly, these amino acids are non-proteinogenic. Humans can synthesize twelve of the 20 proteinogenic amino acids from other molecules intermediate in metabolism, but eight of them (known as “essential amino acids”) must be eaten. (The others are essential too, in that they’re necessary for life, but it’s not essential to eat them.) Other organisms have different sets they can and can’t synthesize.

Obligatory dinosaur moment: Remember how, in Jurassic Park, they explain how the “lysine contingency” would prevent dinosaurs from surviving outside the park? The idea was that the genetically engineered dinosaurs couldn’t synthesize lysine, an amino acid, and would thus be dependent on lysine supplements from the zookeepers. However, no animals can produce lysine; it’s an essential amino acid that’s obtained by eating plants and bacteria that can synthesize it.

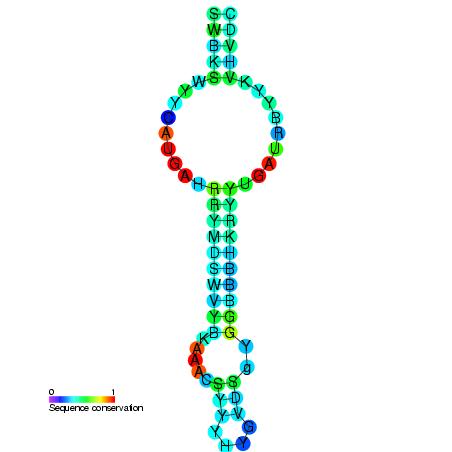

There are two additional proteinogenic amino acids that aren’t coded for in a traditional manner. One of them is called for when your RNA does this:

Which is actually a normal thing, apparently.

One concept that science fiction often fails to address is the fact that even if aliens were chemically very similar to us, the likelihood that they would use the same set of 20 amino acids out of the hundreds of possibilities is low; and the likelihood that the same 19 would be left-handed is astronomically low. So, even if we could coexist in the same atmosphere and grow our crops in the same soil, we would not be able to eat the alien plants or animals and they wouldn’t be able to eat ours! Many of the mirror image and non-proteinogenic amino acids are poisonous to us.

How do herbivores get enough protein, especially ones that eat only grass, which is particularly nutrient-poor? They encourage bacteria to grow on the grass in their gut, and then kill and eat the bacteria!

Conclusion

Okay, I’ve now read enough about biochemistry to last me a very long time. I hope you learned something–I sure did–and if you’re a chemistry expert and caught a mistake or something misleading, please let me know!

The page image is a drawing I did awhile ago of Proburnetia, an early synapsid (mammal relative) that had bumps on its skull which may have supported horns. It…did biochemistry. Like all organisms. Honestly I just didn’t have time to draw anything new this past fortnight. Sorry!