The last time I discussed the mammal family tree, I ended the post in a bit of a hurry and glazed over the relationships between living mammal groups. Now it’s time to go a bit deeper. Cenozoic, ho!

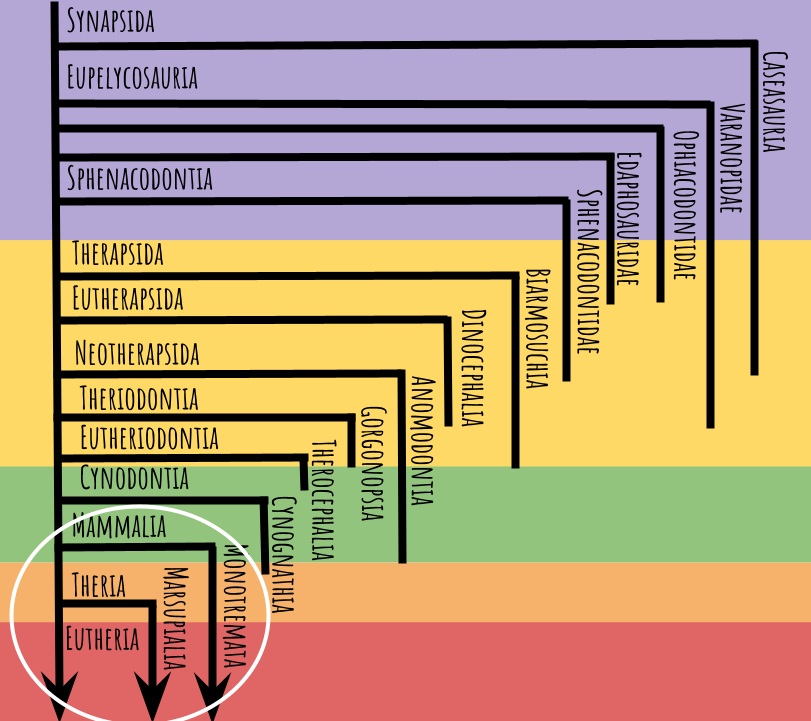

In my last post, we examined this tree:

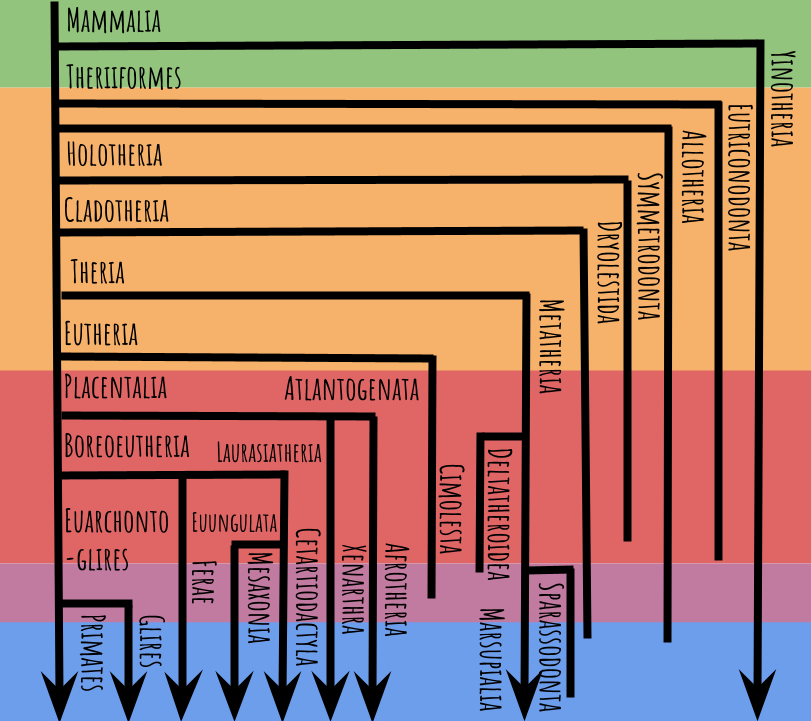

Now we’re going to zoom in on just the circled portion, which expands impressively into this:

The colored bands now represent the Triassic (green), Jurassic (orange), Cretaceous (red), Paleogene (pink), and Neogene (blue), not to scale. Arrows indicate lineages with surviving members, and where a line ends it means the lineage has gone extinct. Note again, many animals fall outside these groups, but I’m just going to focus on the most diverse and charismatic ones.

You’ll notice that a lot of groups have “theria” in their name. That means “beast,” and is a common suffix for synapsid genus names. When someone says “beast,” do you think of a mammalian creature? I guess scientists generally do.

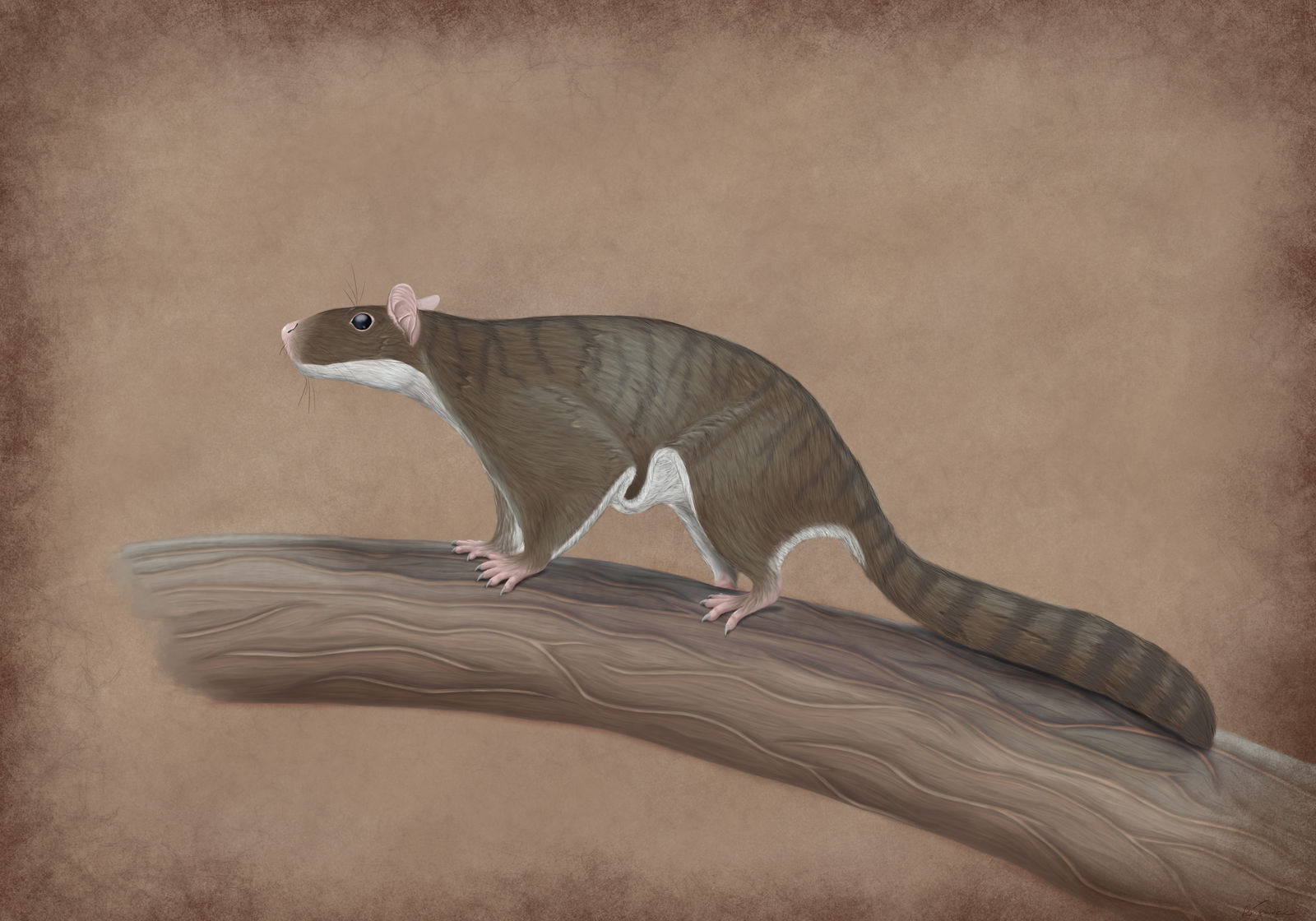

The ancestral mammal body plan looked very much like a rat: plantigrade (walking on the palms and soles), small, long-bodied, dull-colored, with a long snout and long tail. So unless stated otherwise, assume the earliest members of each group discussed below started from this body plan.

Yinotheria

As I’ve stated berfore, there is a gradual transition of features from non-mammal mammaliaformes and true mammals, and there isn’t a defining characteristic we can point at that true mammals have and non-mammals don’t. Instead, true mammals are defined as a crown group: the most recent common ancestor of all living mammals, and all its descendants. This puts the origin of true mammals somewhere in the Triassic Period. Check out how long the yinotherians, which includes monotremes (platypuses and echidnas) have been evolving separately from the rest of living mammals! They are so far from the rest of us that they contribute disproportionately to the genetic diversity of mammals as a whole, and it would be a real shame if they went extinct.

Yinotherians, represented today by the platypus and four to eight species of echidna (depending on who you ask), do quite a few things differently than other mammals. The most obvious thing is laying eggs, but they are also mesotherms, meaning they’re not fully warm-blooded, although this is thought to be a recent adaptation that extinct yinotherians did not share. They can sense electric currents, which helps them detect the tiny animals they eat even in murky water or mud, and lactate despite lacking nipples, sweating the milk out diffusely. They are also ancestrally venomous, although the male platypus is the only living venomous example. And platypuses fluoresce green under a blacklight, as if they weren’t already weird enough! (Flying squirrels and opossums also biofluoresce under UV, but pink. Not much is known about the purpose or origination of this trait.)

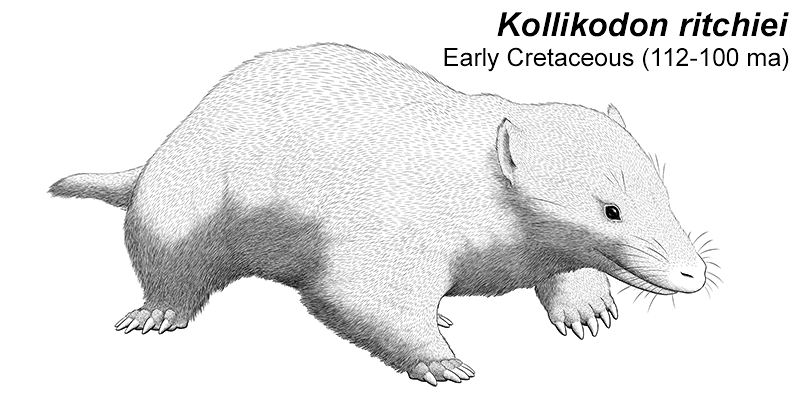

The fossil record of monotremes is really sparse. The oldest members assigned to the group, Steropodon, Teinolophos, and Kollikodon (middle Cretaceous), are known from fragments of jaws and teeth only, which differ from those of modern monotremes in key aspects. That makes it hard to reconstruct what they may have looked like, let alone lived like. Reconstructions vary from the very ratlike to the very platypus-like (molecular clock evidence suggests echidnas descended from a platypus-like ancestor). The oldest unambiguous platypus we know of is Obdurodon, from the Oligocene, 28 million years ago, which looked very similar to the modern platypus, but was about twice as long and kept its teeth into adulthood.

It’s not known for sure how the monotremes managed to survive while all the branches in the tree around them got pruned, but it probably has to do with the living members’ specialized abilities. Their electrosensing allows them to access food sources that other mammals can’t. Plus, the other mammals monotremes had to compete with were metatherians (the group including marsupials), which, no offense to them, are to lepidosaurs (lizards) as eutherians (including placentals) are to archosaurs (crocs and birds). They’re just as derived, but tend to run a little colder and a little dumber.

Eutriconodonta

This group is the first major branch of extinct mammals we’ll look at. They arose in the Early Jurassic and survived until the end of the Cretaceous, dying out shortly before the asteroid impact. This was a very diverse and successful group with a few famous members, like Volaticotherium, a gliding, squirrel-like animal, and Repenomamus, a large badger-like animal famous for having eaten a juvenile Psittacosaurus (small Triceratops relative) right before it died.

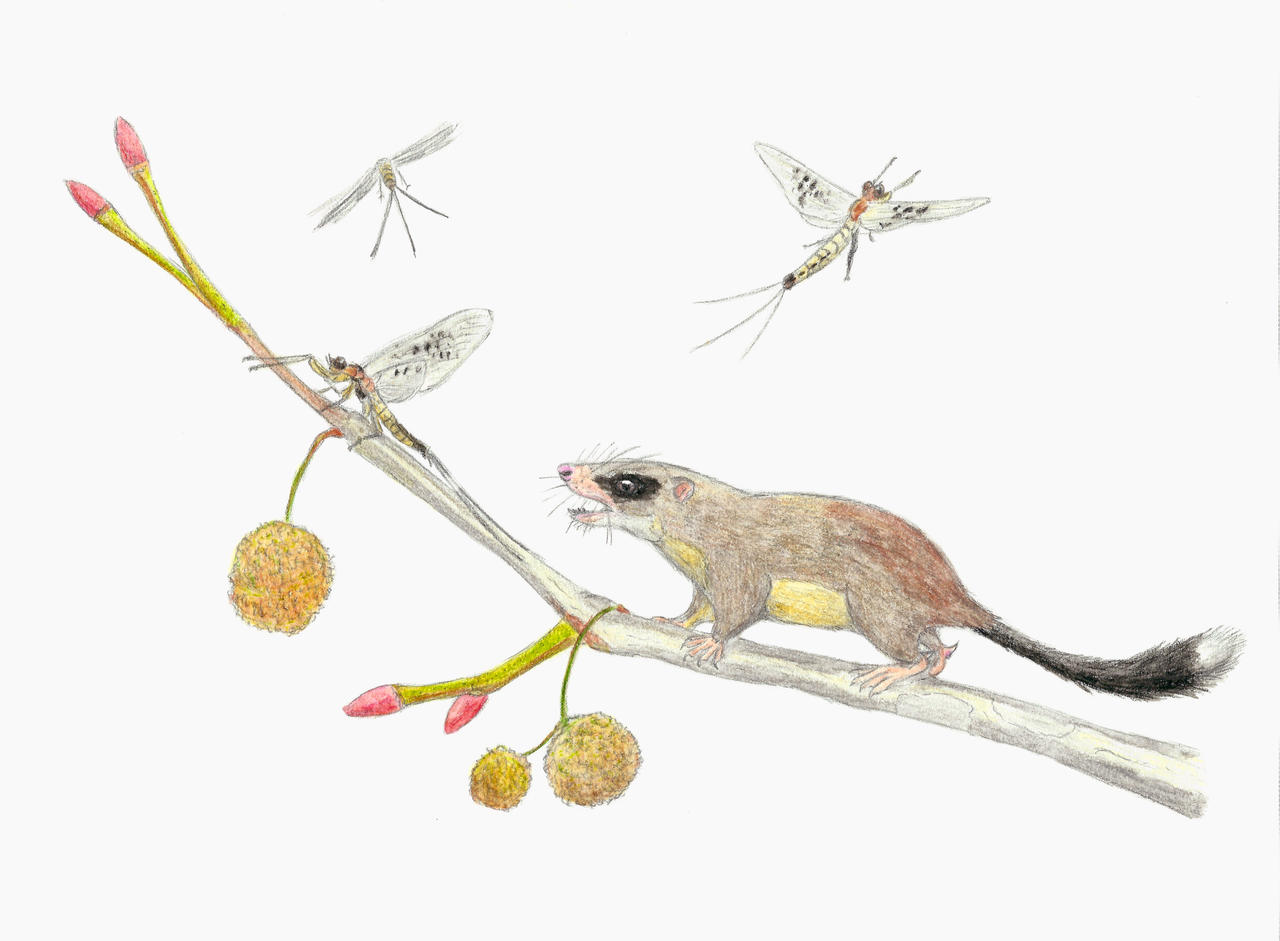

A less outwardly unusual but in fact very derived eutriconodont is Spinolestes, from Early Cretaceous Spain.

This little animal had several features convergent with modern armadillos and anteaters, which are in the family known as Xenarthra (meaning “weird joints”) along with sloths. Xenarthrans have reinforced vertebrae that allow them to exert large forces for digging, and they are the only living mammals that have osteoderms, or bony armor in the skin. Spinolestes had a similar reinforced spine, beefy arms, and osteoderms on its back and hips, as well as hedgehog-like spines. Xenarthrans are quite distantly related to other eutherian mammals, implying that Eutriconodonta was a group with a similar level of diversity!

Allotheria

While the eutriconodonts died out before the non-avian dinosaurs did, the allotheres (meaning “other beasts”) arose around the same time in the Early Jurassic but survived through the Miocene, for a total run of 136 million years! This group included the multituberculates and the gondwanatheres (which may, in fact, be a subset of multituberculates), and were super diverse and widespread both during the Mesozoic and the Cenozoic. During the Mesozoic, fully half of all mammals were multituberculates; after the K-Pg extinction, they were also some of the first to bounce back and radiate into new forms.

This group also includes Gondwanatherium and Sudamerica, the first animals with high-crowned teeth, which are good for chewing tough foods like grass (which literally contains little grains of sand in its leaves). However, it’s a bit of a mystery what they were using these teeth for, since although grasses existed in the Paleocene, they were not widespread until much later. Either these multituberculates lived in special areas with lots of grass, or high-crowned teeth are also useful for processing some other type of food as well.

The last multituberculate known is Patagonia, from Miocene, well, Patagonia (Argentina), which was similar in appearance and lifestyle to a gopher. No one factor caused this group’s extinction, but rather a combination of climate change, new types of vegetation, and competition from other mammal groups led to their gradual decline and eventual demise.

Symmetrodonta

Symmetrodonts were a group of small carnivore / insectivores from the Cretaceous Period, with just one known member surviving through the K-Pg boundary. This group is possibly paraphyletic, but it’s still a conceptually useful and commonly used grouping, so I’ll use it here. Some symmetrodonts had venom-delivering spurs on their feet like platypuses, lending support to the theory that this feature is ancestral to all mammals but was later lost.

Another notable symmetrodont is Spalacotherium, which, while only known from isolated teeth, may be the smallest known mammal to ever live. Its molars were only a quarter of a millimeter across, about half the size of the molars of the smallest comparable mammal today, the Etruscan shrew, which is about five centimeters long (not including the tail) and weighs two grams (less than a dime). That is a really small mammal–it’s more comparable to most insects!

Dryolestida

This is the last group we’ll discuss before we head back to the realm of the living: the dryolestids. These were very common in the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods, represented by mostly small, insectivorous, burrowing or arboreal forms. Some survived beyond the Mesozoic, but so far we’ve only found two genera: Peligrotherium, a dog-sized herbivore from the Paleocene, and Necrolestes, a mole-like insectivore from the Miocene. That implies a ghost lineage of at least 38 million years!

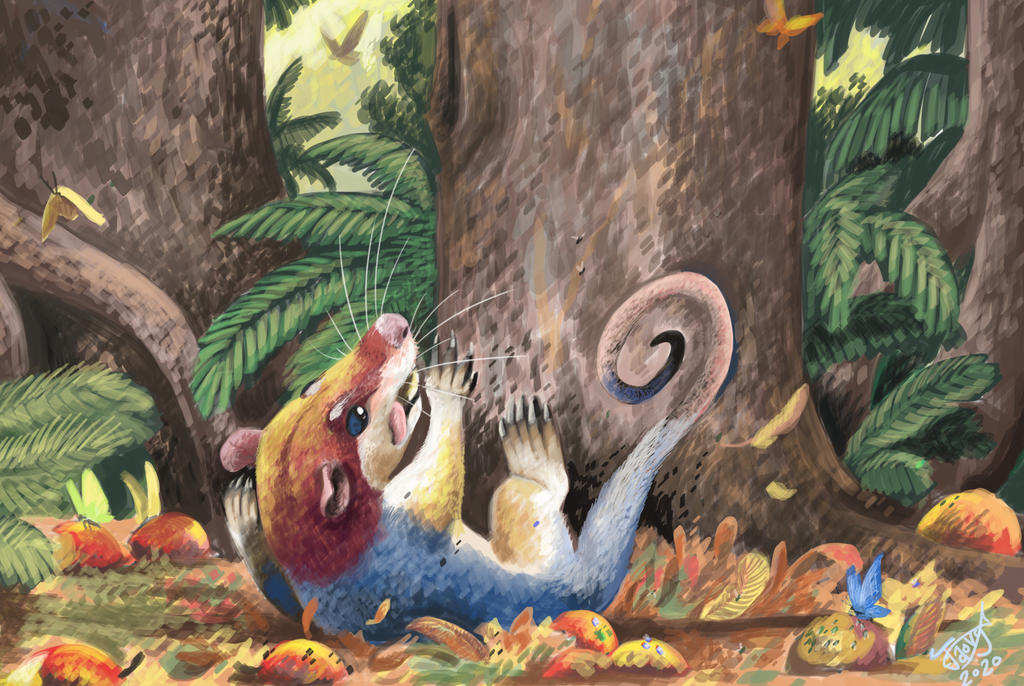

One dryolestid that made headlines when it was discovered in 2011 was Cronopio, a squirrel-like animal with saber teeth–basically the real life version of Scrat, the saber-toothed squirrel from the movie Ice Age. Since that movie came out in 2002, the striking similarity is pure coincidence. We have no idea what it was using its saber teeth for, given that its snout was so long and thin that it couldn’t exert much bite force with them. Perhaps they were a sexual display structure.

One group of younger dryolestids, the mesungulatoids, became somewhat larger-bodied and developed teeth similar to those of modern ungulates (hoofed animals).

Metatheria

We’ve made it back to familiar territory: the metatherians, which include marsupials, but also a lot of interesting extinct relatives. In the Cenozoic, Metatherians ruled the Southern Hemisphere while eutherians ruled the Northern, and the groups diversified independently for nearly the entire era. They only reencountered each other 2.7 million years ago in the Great American Biotic Interchange, when South America connected to North America (and even more recently for Australian metatherians, with colonization by humans). The two groups each converged on similar solutions to many of the same problems, resulting in lots of marsupial “equivalents” of placental mammals: marsupial lion, marsupial wolf, marsupial saber-toothed cat, marsupial tapir, marsupial mole, etc. Since the practice of taxonomy was developed in the Northern Hemisphere, the marsupial member of the pair is always named after the placental and never the other way around. See my post on convergent evolution for more details!

Deltatheroidea

Deltatheroidea was a mostly-Cretaceous group that expanded its presence when the eutriconodonts started to decline. They were known from the Northern Hemisphere, the last time metatherians would be there until the Pleistocene, and were mainly small to medium-sized insectivores and carnivores. One of them, Lotheridium, had impressive saberlike canine teeth (more details in my post on convergent evolution) but was more the shape of a saber-toothed wombat than cat. Another notable member, Deltatheridium, may have fought or preyed upon dinosaurs: a fossil skull of the very small dromaeosaur Archaeornithoides exhibits Deltatheridium-shaped bite marks that later healed.

Sparassodonta

The other major extinct branch of Metatheria was the charismatic Sparassodonta, endemic to South America, which includes famous members such as Thylacosmilus, the metatherian equivalent to a saber-toothed cat (though I would argue that Thylacosmilus committed more fully to saber toothing than any other), and the aptly named metatherian hyena-like animals Borhyaena and Proborhyaena.

Sparassodonts gradually declined over the course of the Miocene and went extinct in the Pliocene, before the Great American Biotic Interchange, which means competition with eutherian carnivores wasn’t the reason they died out. Other possible reasons include cooling climate and increased seasonality, and competition with early true marsupials such as large-bodied opossums.

Marsupialiformes

The rest of the diversity of metatherians, living and dead, is found in the marsupials and their closest relatives. You’re probably familiar with kangaroos, wombats, koalas, opossums, Tasmanian devils, and sugar gliders, so I’ll just highlight some of the more interesting extinct members here.

The extinction of the Ice Age megafauna, which wiped out the mammoths, giant bears, and ground sloths in the Northern Hemisphere, also affected the Southern–hippo-sized wombats like Diprotodon and lion-sized carnivores like Thylacoleo used to be common in Australia, but died out due to a combination of post-Ice Age warming and archaic human activity. In South America, marsupials coexisted with whatever placental mammals were able to raft over from Africa, including monkeys, cavies, and South American native ungulates (SANUs–we’ll talk about them more later), but they declined severely during the Great American Biotic Interchange, leaving only the two families of American marsupial we still have today: opossums and shrew opossums.

A notable early marsupialiform known from North America in the Late Cretaceous was Didelphodon, an opossum-like animal with a gnarly bite.

Paleontologists often complain that people give a disproportionate amount of attention to charismatic megafauna (“Save the pandas!”), while the small, gross, and ugly animals (e.g. bees, bats, frogs, spiders) go neglected even if they’re ecologically more important. This is a completely valid point–sorting animals by size, cuteness, or coolness is definitely not a rational way to do science or conservation. Unfortunately, I’m a huge fan of charismatic megafauna. I just can’t resist their charismatic allure. So, I apologize for the megafauna-centric focus of this post, but I won’t promise to stop.

Some of the largest marsupials from the fossil record include the aforementioned Diprotodon (at 2.8 tonnes, the largest marsupial ever) and other giant wombats, which are the only marsupials known to have seasonally migrated. There’s also Palorchestes, which would’ve been a sort of marsupial equivalent to the placental chalicotheres (more on them later)–top browsing herbivores with long arms, long claws, and short back legs, good at reaching up into trees.

Some notable large marsupial carnivores include Thylacoleo, a wombat that wanted to be a lion, and Thylacinus, the thylacine, a numbat that wanted to be a wolf. The latter was a bit more conservative in its approach, while the former was one of the most bizarrely specialized carnivores ever to live. Unlike most carnivores, which turn their canine teeth into weapons, Thylacoleo used its incisors for grabbing large prey and its bolt-cutter-like carnassial premolars for quickly dispatching them. It also had opposable thumbs with a large claw, for grappling with large prey. It was so specialized that it may have been unable to catch any small prey. Thylacoleo also had the strongest bite of any mammal–not just of any marsupial, but any mammal. Maybe we should call lions “placental Thylacoleo” instead!

Recently, colorized footage of the last living thylacine was released, so you can see the real thing here! Interestingly, very few predators throughout history were digitigrade, or walking on their hind toes, like dogs and cats; all the sparassodonts, Thylacoleo, and many more basal relatives of dogs and cats walked on flat feet. But not the thylacine! Digitigrady is a more energy-intensive, but quieter and faster way of moving. The only other digitigrade carnivores I know of are the mesonychids, which are relatives of artiodactyls (pigs, whales, cows, etc), which I’ll discuss more later.

Eutheria

Finally, here’s the group that includes us, as well as most other mammal diversity in the modern world. The eutherian lineage branched off as far back as the Jurassic, with the small ratlike Juramaia and Eomaia hailing from Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous China, respectively. These weren’t true placental mammals–they had a pelvis that wouldn’t’ve allowed them to give birth to large young, instead giving birth to tiny, undeveloped neonates similar to modern marsupials. However, we know they’re more closely related to eutherians than metatherians due to various minor anatomical features of the leg bones and teeth that are unique to each group.

Cimolesta

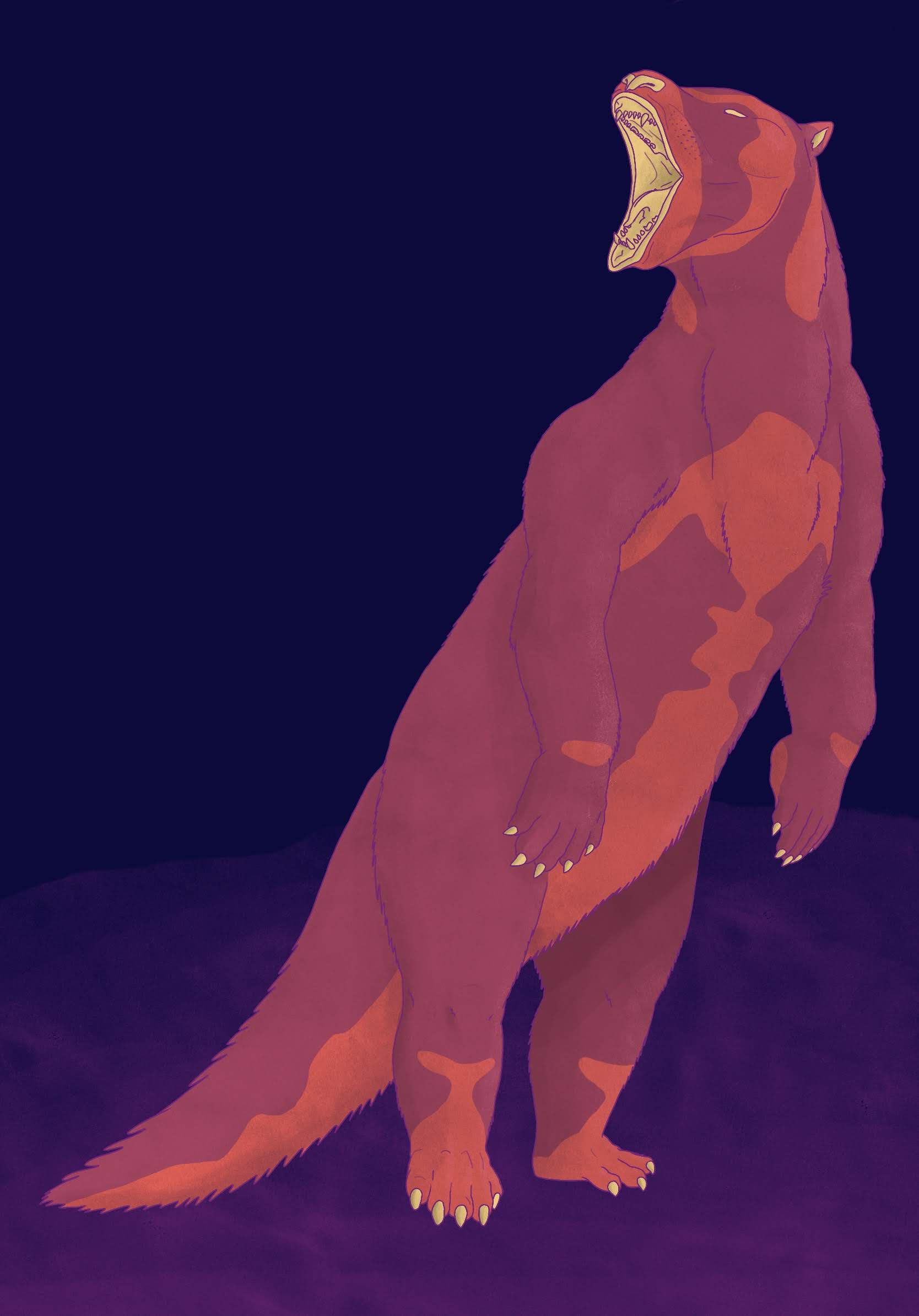

Like Eutriconodonta, Allotheria, and Metatheria, Cimolesta is yet another clade of mammals that insisted on reinventing the wheel, coming up with their own biological approaches to all the same ecological niches. They arose in the Late Cretaceous and radiated rapidly after the K-Pg extinction, coming up with bearlike, weasel-like, squirrel-like, otter-like, hippo-like, shrew-like, and no-living-animal-like forms, before those forms existed among the placentals. Some of these I highlighted in my Paleo Biome Profile on the Messel Pit. As a group, cimolestans lived fast and died young, exploding in diversity in the first handful of millions of years of the Cenozoic but not making it past the end of the Paleogene. I can’t find any information on why it’s believed they died out, but if I had to guess I’d say it’s probably related to climate change and competition with placental mammals.

In contrast to the many cimolestans whose lifestyle is obvious from their anatomy due to similarities to a modern clade, the taeniodonts were a group of cimolestans that don’t resemble anything else. They had ever-growing chisel-like teeth in the front of their mouths, like a rodent, except derived from the canines rather than the incisors (the opposite of what Thylacoleo did!), super-short snouts, and long, trowel-like claws. For a long time they were assumed to be root eaters, but analysis of the wear patterns on their teeth refute this hypothesis without proposing a new one. So although we believe they were herbivores, we don’t know much else.

Atlantogenata

We’re on the home stretch–Placentalia! The group containing every mammal you’ve heard of that we haven’t talked about yet. The most distantly related group to most other placental mammals is Atlantogenata, which includes Xenarthra (sloths, armadillos, and anteaters) and Afrotheria (elephants, sirenians, hyraxes, elephant shrews, tenrecs, and golden moles). Yes, that means that golden moles are more closely related to elephants than they are to true moles! Atlantogenatans have been evolving separately from other placental mammals for so long that morphology don’t mean nothin’ when it comes to genealogy.

While xenarthrans today are mostly small, other than the giant anteater, they used to have quite a few large members, such as the giant ground sloths Megatherium and Megalonyx (the latter being the only prehistoric taxon named by an American president–Jefferson, by the way), the semiaquatic sloth Thalassocnus, and the giant armadillo Glyptodon (which is invariably compared to a VW Beetle in size). As I mentioned above with regards to the eutriconodont Spinolestes, xenarthra means “strange joints,” since these animals’ spines are reinforced. This is a helpful adaptation for digging, which is important if you live in giant burrows like the 2.6 tonne ground sloth Lestodon, or if you eat large quantities of insects that live in underground colonies.

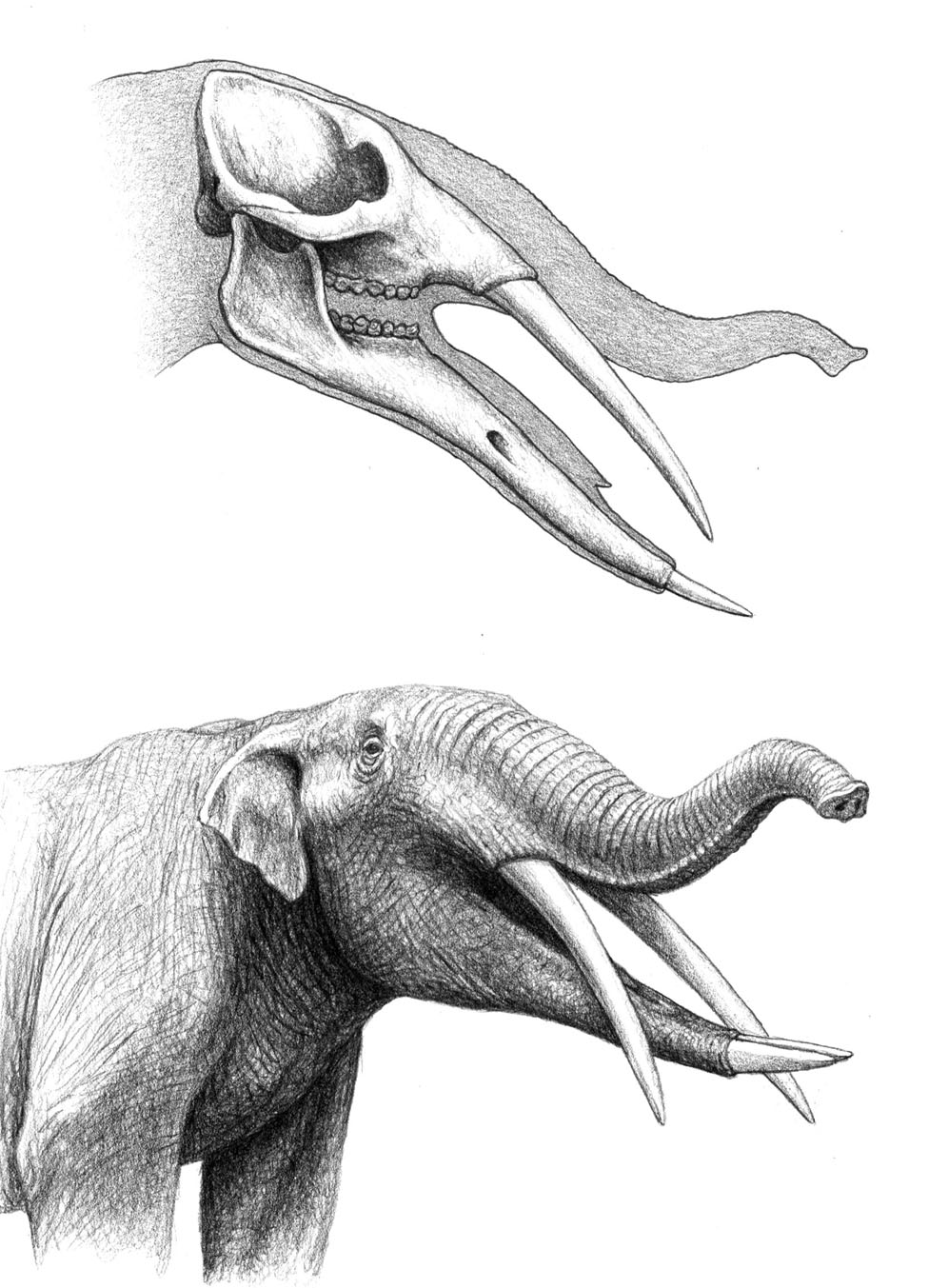

Living afrotherians are extremely disparate in shape and function, but not rich in species: they make up a third of the genetic diversity of mammals in Africa, but only 6% of the species. In the past, more of that evolutionary space was filled out, with many types of proboscideans such as shovel-tusked gomphotheres, mastodons, mammoths, and even dwarf elephants and dwarf mammoths found on Mediterranean islands, which were only three feet at the shoulder. The giant sirenian known as Steller’s sea cow is another notable recent extinction, with the last one dying in 1768.

One group that might be included in Afrotheria is the South American native ungulates (SANUs) I mentioned before. Before the Great American Biotic Interchange, there were many animals in South America that looked a lot like Northern Hemisphere animals, but a bit…off. The toxodontians looked like rhinos, the litopterns like llamas, astrapotherians and pyrotherians like elephants, xenungulates like tapirs, and Pachyrukhos looked almost exactly like a rabbit. While morphological characteristics place all of these animals in Afrotheria, recent genomic analysis has tentatively put at least some of these groups–Litopterna and Notoungulata–in Mesaxonia, along with horses and true rhinos.

Laurasiatheria

In this clade, we find the true ungulates (and maybe those problematic SANUs), both of the odd-toed (horses, rhinos, and tapirs) and even-toed (cows, pigs, hippos, whales) varieties, as well as Ferae (cats, dogs, pangolins).

While all terrestrial ungulates today are herbivores, that certainly wasn’t the case in the past, with three main groups of hoofed carnivores: the mesonychids, the entelodonts or “hell pigs”, and Andrewsarchus (it may be related to entelodonts, or perhaps to hippos and whales). Mesonychids were a group of basal ungulates, not part of Mesaxonia or Cetartiodactyla, which looked very much like a cross between a pig and a wolf.

Andrewsarchus and the entelodonts are definitely the most exciting of the extinct non-whale artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates). For details and pictures of whales, see my post on whale evolution!

And while we’re here, I can’t forget the page image, Myotragus, which I’ve taken to calling “the naked dog-goat”. It lived from the Pliocene to Holocene on the Mediterranean islands of Mallorca and Menorca. There were no predators and scarce resources on these tiny islands, so Myotragus developed a suite of very strange characteristics: forward-facing eyes, which allow depth perception but reduce field of vision; ever-growing lower incisors like a rodent, with no incisors at all on the upper jaw; and cold-bloodedness, to reduce energy usage. Most paleoart depicts them as having a weird, humanlike face due to the short snout and forward-facing eyes, and being fuzzy because most goats are fuzzy. The result looks like really bad taxidermy. Instead, I chose to make its face more reminiscent of a different animal with a short snout and forward-facing eyes–a dog–and made it naked like a naked mole rat, because as an ectotherm you want as little insulation between yourself and the environment as possible. (Yes, naked mole rats are also cold-blooded.) Some damage on the horns of some skulls of Myotragus led people to hypothesize that they were tamed by early humans, who trimmed their horns. However, the marks are more consistent with Myotragus gnawing on each other’s horns to reclaim minerals. Yummy.

Myotragus would have been very slow-moving and unable to run very fast or jump. It went extinct around 3000 BC when humans arrived on the islands.

Mesaxonia is the name of a newly proposed clade including the more familiar Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) and the SANUs. There are lots of charismatic extinct animals in this clade, but I actually included pictures of basically all of them (Chalicotherium, Uintatherium, and Paraceratherium) in my previous Mammal Family Overview post, so I won’t include them again here. Alas, you’ll just have to read more of my blog.

Among the carnivorans, there have been a lot of iteration on the theme of “lion” before cats actually showed up. The creodonts, including hyaenodonts and oxyaenodonts, looked a lot like big cats, but had a plantigrade stance and were unable to turn their front feet inward to grasp or slash, relying instead on their huge heads and jaws to take down prey. They also had teeny brains compared to cats and dogs, which may have been a factor in their eventual replacement. The enormous hyaenodonts Simbakubwa and Sarkastodon weighed up to a tonne, and were therefore among the largest terrestrial mammalian predators ever–around the same size as Andrewsarchus. Machaeroides, an oxyaenodont, would have looked like a mini saber toothed cat, weighing only 10 to 15 kilograms. PBS Eons, the Youtube channel, has an episode on hyaenodonts, which I’d recommend if you’re interested in more information!

Among true carnivorans, a notable extinct group is Borophaginae, or the “bone crushing dogs”. These were canids endemic to North America from the Oligocene to the Pliocene that had hyena-like faces with, you guessed it, bone crushing teeth. They declined due to competition as felids arrived from Asia and grasslands spread, where true canines, which are very efficient pursuit hunters, had an advantage. PBS Eons also has an episode on borophagines. Convenient!

Euarchontoglires

There’s not much left to say about this last group, which includes rodents, rabbits, and primates, (yes, rabbits and rodents are our closest non-primate relatives, which is one reason so much medical experimentation is done on rats and mice) but of course I must call attention the most massive members of the clade.

Josephoartigasia was an enormous caviomorph rodent (relative of guinea pigs and chinchillas) from Pliocene to Pleistocene South America. It weighed up to a tonne, which is ten times more than the largest extant rodent, the capybara. What advantage was conferred by being so large? Perhaps defense against the sparassodonts, saber-toothed cats, and terror birds that shared its environment.

Gigantopithecus was a very large relative of orangutans from Pleistocene southern China. It’s only known from a bunch of jaws and teeth, so it’s difficult to make an accurate size estimate, but it may have reached 300 kilgrams, only a bit larger than a silverback gorilla. In the 2016 remake of The Jungle Book, King Louie is changed from being an orangutan (since orangutans live in southeast Asia, not India) to being a last-of-his-kind Gigantopithecus, which probably did range into India. As a bonus, this gave the filmmakers license to make him dramatically enormous.

We made it! Sorry this post was a tad late. It got quite a bit longer than I originally anticipated. I hope you have a slightly better idea of how various extant and extinct mammals are related to one another, but if not, I hope you were at least entertained by this roll call of giant animals.

Image credits

Kollikodon 1 Kollikodon 2 Volaticotherium Spinolestes Taeniolabis Ptilodus Adalatherium Chronoperates Dryolestes Cronopio Peligrotherium Patagonia and Necrolestes Deltatheridium Lycopsis Proborhyaena Didelphodon Diprotodon Palorchestes Thylacoleo Stylinodon Coryphodon Lestodon Gomphotherium Astrapotherium Macrauchenia Toxodon Sinonyx Archaeotherium Embolotherium Simbakubwa Epicyon Josephoartigasia Gigantopithecus