It’s not exactly controversial to state that white men hold the most power of any demographic in the world today. But why? Did it have to be this way? Or if you ran a simulation of human history over again, would a different group come out on top? Read on to find out.

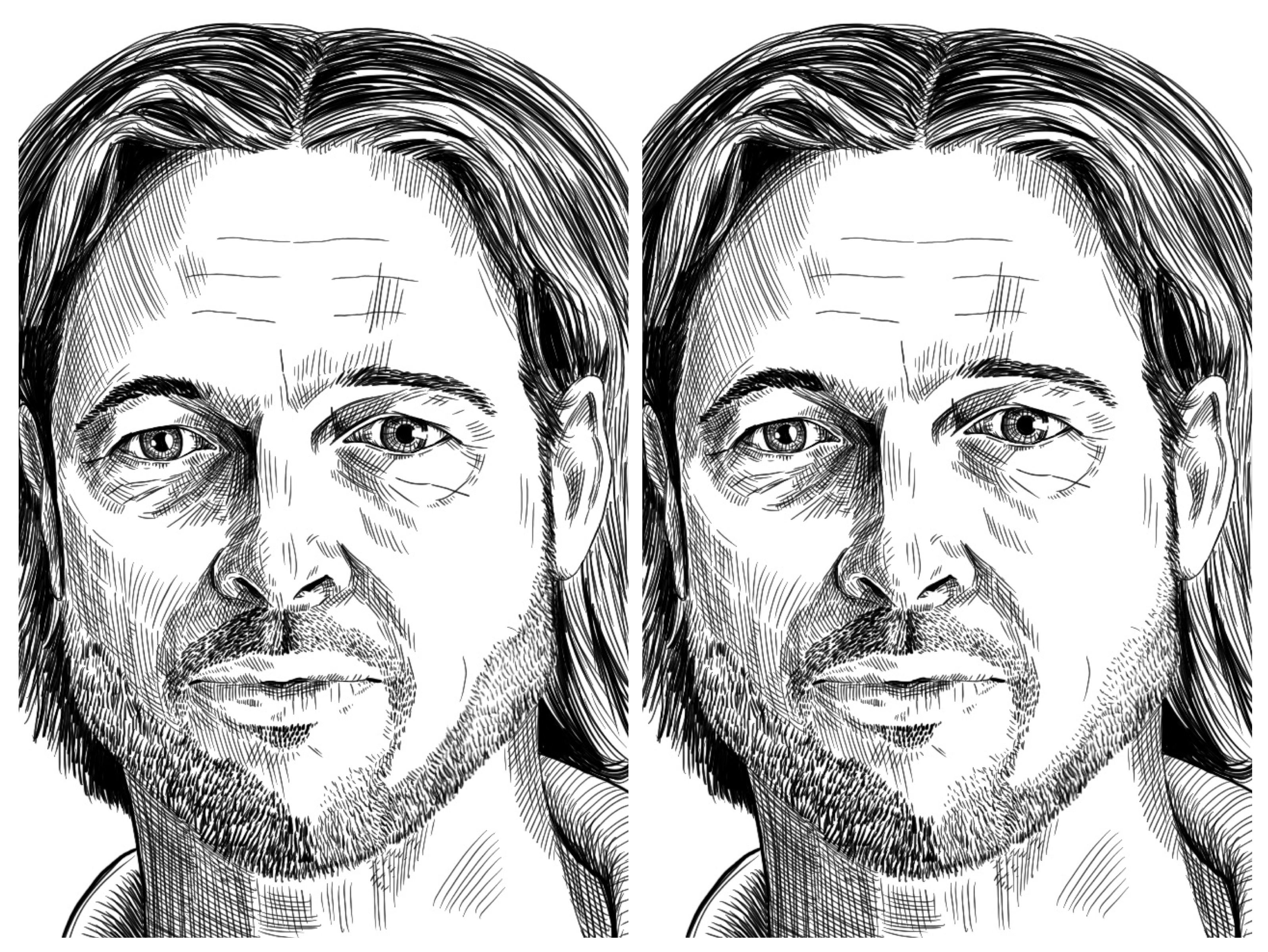

Evolution of skin color

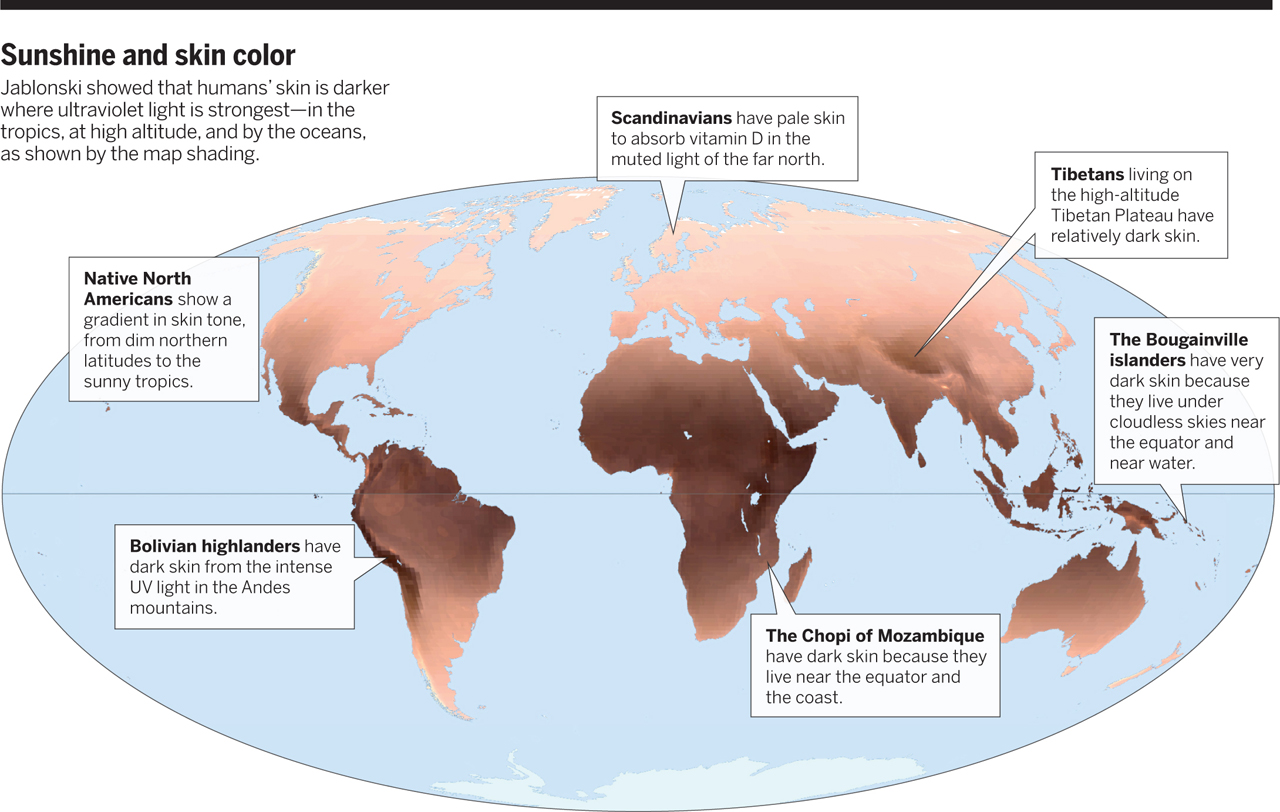

Let’s start with the easiest aspect to explain. Skin color is an adaptation to the level of UV light in the environment and to the amount of vitamin D available in the local diet. The higher the UV intensity, the more pigmented one’s skin must be to avoid sunburn and skin cancer; with low UV intensity, pigment interferes with one’s ability to synthesize vitamin D, so less is beneficial. If one’s diet contains more vitamin D than average, like people who eat a lot of fish, one can afford to be a little darker for the sun protection.

High UV intensity occurs around the equator, at high altitudes, and near oceans and snow that reflect light. Note how little land there is south of the equator–a vast majority of the earth’s land area is in the Northern Hemisphere, and almost all the land in the Southern Hemisphere is close to the equator, that is tropical or subtropical. With our planet’s current layout, “temperate” essentially means northern. We’ll come back to this later.

Aside: the darker the skin, the spicier the cuisine

As a side note, plants with spicy fruits (black peppercorns, Sichuan peppercorns, and chili peppers, which are not closely related to one another–an example of convergent evolution) only occur in the tropics. This is probably the case due to a combination of reasons, but as that’s not what this post is about, I didn’t dig too deeply into it. For one thing, capsaicin is percieved as spicy by mammals and fungi, but not by birds (or other reptiles, or insects). This is to encourage birds, with their short digestive tracts and ability to fly great distances, to eat the colorful fruits and disperse the seeds, and to keep mammals, with their intense digestion and more sedentary lifestyles, away. This is also why peppers and chilies are colorful, but not very aromatic: to attract birds, with their superior color vision, and to fly under the radar of the olfactorily-gifted mammals. You can read more about that in my post on evolutionary anachronisms like the avocado. Birds are highly diverse and abundant in the tropics, and the dense foliage of jungles means that mammals and other land-bound creatures can’t easily travel far, intensifying the selection pressure for plants to prefer birds. Mammalian herbivores are also abundant in the crowded, biodiverse jungle, and it’s possible that the metabolic pathway leading to capsaicin production works better at tropical temperatures and humidity levels.

All this to say, tropics go hand in hand with dark-skinned humans and also with spicy foods. And despite global trade allowing humans to import foods from anywhere in the world, modern cuisines generally stick to this pattern. The only exception is Korea, which doesn’t have any native peppers, but adopted them with enthusiasm for some reason.

Historical Atlas of World Mythology

Back in the eighties, the comparative mythologist (is that even a real title?) Joseph Campbell (of Hero With a Thousand Faces fame) published a four-volume series called The Historical Atlas of World Mythology, in which he proposed a general framework to explain the evolution of a culture’s mythology through different levels of technological progress and in different climates. While Campbell, being a mythologist and not an anthropologist, did not provide quantitative evidence to support his model, later models and hypotheses bear a lot of similarities to the one proposed in The Historical Atlas, so it seems that Campbell intuitively sensed an actual truth. And his categories have catchy names, so I’ll use them. (Whether other models Campbell proposed, such as the Hero’s Journey and the Monomyth, are supported by evidence is out of scope of this post.)

His two main primitive mythologies, the Way of the Animal Powers and the Way of the Seeded Earth, apply to hunter-gatherer societies in temperate and tropical zones, respectively. Each has a lot to unpack, so I’ll describe them one at a time.

The Way of the Animal Powers

The Way of the Animal Powers describes cultures in which most calories come from hunting large prey, such as indigenous Americans, Stone Age Eurasians, and some grassland Africans. This survival strategy works well when large prey is abundant and easy to track, as humans are good persistence hunters and can walk a lot farther than most quadrupeds before needing to rest. Big packets of calorie-dense fat and meat are much more efficient in terms of time investment for feeding your tribe than gathering thousands of berries, roots, and mushrooms, so when possible, this is the best strategy.

To hunt large game, one needs strength (even when using a tool that provides mechanical advantage like a bow, sling, or atlatl), stamina, and speed, and incurs a good amount of danger. These are all things men tend to be better at than women. The physical characteristics are obvious and uncontroversial. But why are men less risk-averse? This is because of the way animals sexually reproduce. A man is biologically capable of siring near-infinite children in his lifetime, while a woman can only have a dozen or so, and only about one per year. Furthermore, the woman is stuck carrying a calorically-expensive pregnancy and subsequently breastfeeding and caring for a hungry, useless (at first) child, which is an enormous drain on resources. This incentivizes women to be very careful who they allow to impregnate them. And that means that the best potential father gets to mate with all the women in the tribe, while all the rest of the men have zero offspring.

In practice, this isn’t how it turns out, because (a) women have variable preferences in how they judge men, (b) men who are unsuccessful under that system are incentivized to implement rules that improve their chances, (c) women benefit from men helping to raise their children, and therefore want to minimize the number of other women requiring the father’s attention, and (d) lots of other historical, cultural, and psychological reasons. But the “men audition, women choose” structure is still there underneath it all.

Thus, for men, reproduction is evolutionarily all-or-nothing, and they need to take risks in order to have a shot at being a hero and reaping the genetic reward. Being a middling, conservative guy gets you no girls. Men are forced to risk life and limb when the situation demands they go out and bring down a mammoth.

(Our biology compensates for the higher likelihood of men dying before reproducing through an increased likelihood of having a boy relative to a girl baby under neutral conditions. 1.06 boys are born for each girl, and by the time they all reach reproductive age, the ratio is 1:1. When the mother is under stressful conditions, though, the likelihood of a girl–a safer bet–increases. Here’s a good MinuteEarth video explaining in more detail.)

So in the Way of the Animal Powers, we have men going out and hunting large game. This makes them the breadwinners in these societies–they bring in a vast majority of the calories that sustain the group. And this gives them power over non-hunting members like women, since men control access to the food. The result is that Animal Powers societies–that is, temperate ones–are patriarchal, or ruled by men.

The Way of the Seeded Earth

The Way of the Seeded Earth describes cultures that don’t have access to large prey in open habitats–those in dense jungles in the tropics–and therefore must forage at a smaller scale for their livelihood, gathering fruits, nuts, berries, and hunting small prey. Men and women are on equal footing at this type of foraging, bringing in equal calories at the end of the day. (Too bad there’s not a type of foraging that actually favors women. That would be a neat case study.)

Joseph Campbell claims that since in the jungle, birth and death are all around, with lots of decomposing organic matter forming nurseries for new life, this is why tropical cultures are more likely to practice human sacrifice. They see that good new things come out of death, so to increase fertility of the land and their tribe, they sacrifice life. He also claims that the salience of birth in the jungle causes these cultures to worship mother deities and women’s ability to make babies, leading to societies in which women hold more power.

Whether Campbell has actually identified the cause or not, the observations he’s trying to explain are true. Polyandry, or the practice of one woman simultaneously marrying multiple men, only occurs in the tropics (though wherever polyandry occurs, polygyny, or one-man-many-wives, also occurs), as do matrilineal societies, which track inheritance and transmission of power through the mother’s line. There are no true matriarchal societies, since as I said above, there’s no type of foraging humans do that women are strictly better at than men. But tropical societies tend to be much more gender-equal than temperate ones.

The Way of the Celestial Lights

Unfortunately for women, agriculture is much easier and more productive to practice in temperate climates than in tropical ones. Agriculture was invented in the Middle East and quickly spread across the world from there, as even in places where it was difficult, it still produced more calories with less work than foraging. However, the caloric yield per hour of work is much higher in places you don’t have to cut down hundreds of trees before you can even till the soil. And soils are way less fertile in the tropics than in temperate regions (here’s another good MinuteEarth video explaining that counterintuitive fact). Therefore, after the invention of agriculture, Animal Powers cultures were able to grow their populations, and their power, much quicker than Seeded Earth ones. Campbell calls Animal Powers cultures that have gone agricultural the Way of the Celestial Lights, because those people had the free time, energy, and ability to stay in one place for enough time to catalog and map the stars, and they began to believe in heavenly deities rather than animal spirits.

Due to their ancestry as patriarchal Animal Powers cultures, Celestial Lights cultures carried the torch of oppressing women into the technological age. And since they lived in temperate zones, they were pale-skinned relative to the Seeded Earth cultures they steamrollered later on. That is how the white man got his power. Temperate conditions cause white skin, favor men as breadwinners, and are more productive to farm, leading to economic domination.

The Plough Hypothesis

Now to put some numbers to this very hand-wavey storytelling. Does Campbell’s theory hold up under scientific scrutiny?

In short, it does. A testable conjecture known as the Plough Hypothesis (spelled the British way because it was first proposed by Englishwoman Ester Boserup in 1970) states that the heavier the plough traditionally used in a culture, the less power women hold among their descendants today. This hypothesis was rigorously tested in the 2011 paper, “On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough” by P. Giuliano, A. Alesina, and N. Nunn, and it showed a statistically significant (p < 0.01) and explanatory effect under all tested conditions.

The reasoning is that to control a heavy plough and the big ox pulling it, the user needs significant upper body strength and grip strength, both of which average 40% higher in men than women. Some cultures use a light plough pulled by a smaller animal, and some don’t use a plough at all, instead using hand tools like hoes and seeding stakes, which don’t require much strength to use. Heavy ploughs also reduce the number of laborers required to farm a given area, “allowing” non-farmers the “luxury” of staying at home and not working. Given the efficiency of a heavy plough and big ox, this is employed when possible: when the ground is not too steep, rocky, wet, or frozen, i.e. in temperate zones. This is quantified by identifying “plough-positive” and “plough-negative” crops, or crops that benefit from plough use and those that don’t.

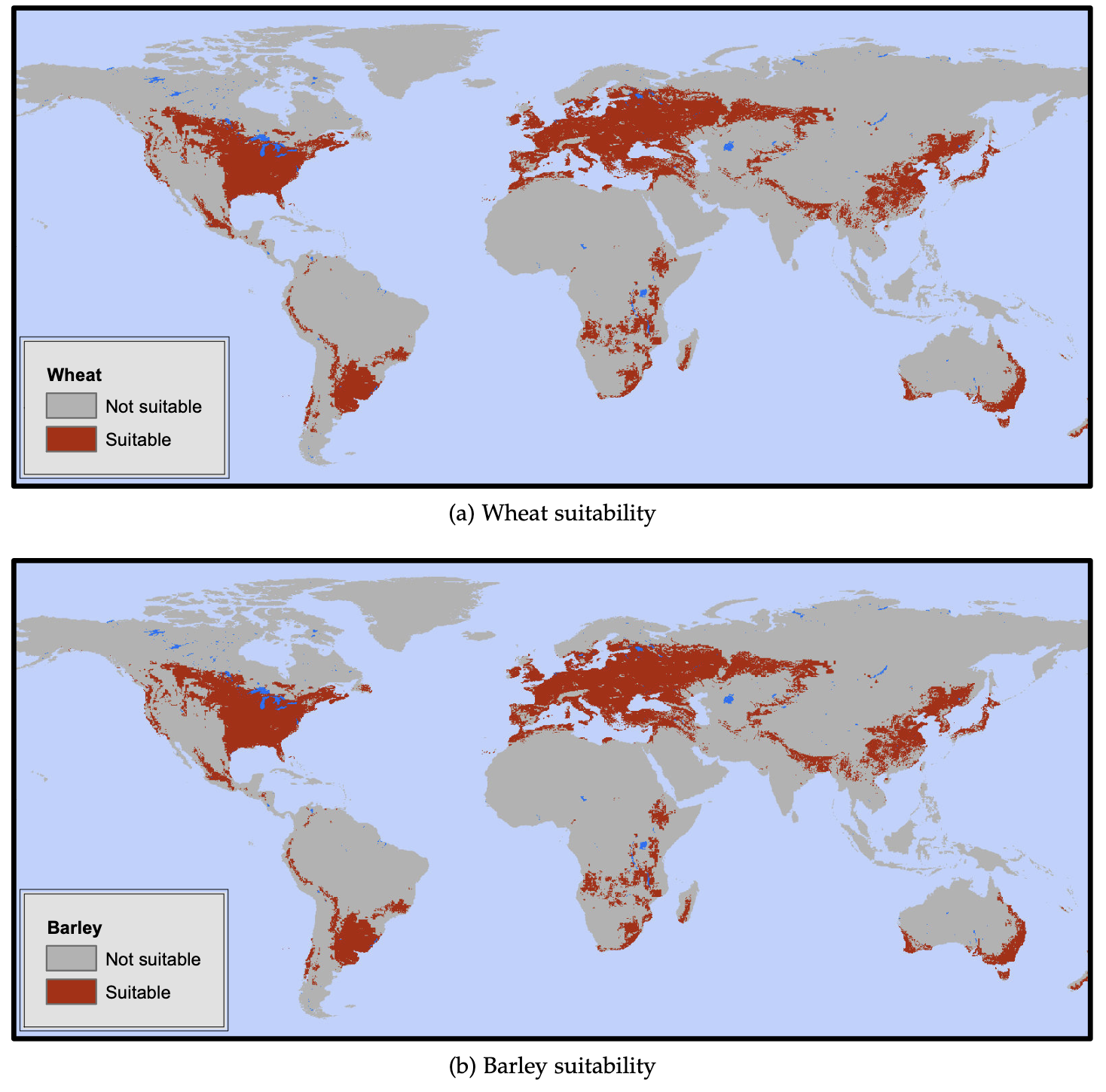

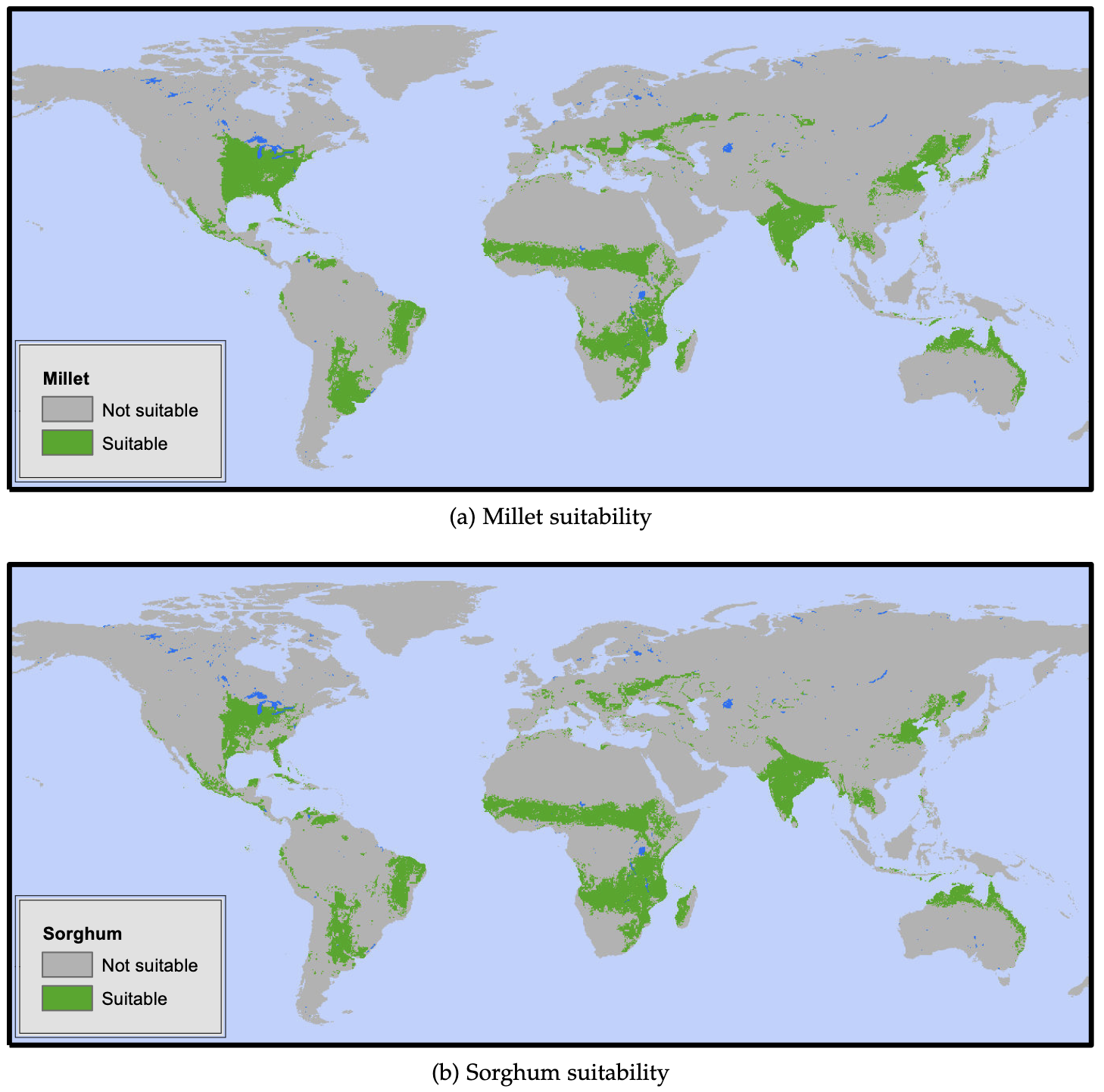

Plough-positive crops, which include wheat, teff, barley and rye, tend to have shorter growing seasons and tend to be cultivated on relatively large expanses of land (per calorie of output) that tends to be flat, with deep soil that is not too rocky or swampy. Plough-negative crops, which include sorghum, maize, millet, roots, tubers, and tree crops, tend to yield more calories per acre, have longer growing seasons, and can be cultivated on more marginal land. (Giuliano, 2011).

To give the most apples-to-apples comparison, the authors compared just the plough-positive cereal crops wheat, barley, and rye to the plough-negative cereal crops millet and sorghum. All of these are “cereals that have been cultivated in the Eastern Hemisphere since the Neolithic revolution…require similar preparations for consumption, all being used for flour, porridge, bread or in beverages…[and] produce similar yields and therefore neither [set] clearly dominates the other in terms of the population it can support”. Here are the eco-maps showing where in the world you can grow these crops:

Clearly, wheat and barley, plough-positive crops, grow best in temperate zones while sorghum and millet, which are plough-negative, do better in the tropics. That shouldn’t surprise you–who here has eaten sorghum or even knows what it looks like? You’re unlikely to unless you hail from a culture that traditionally utilizes it.

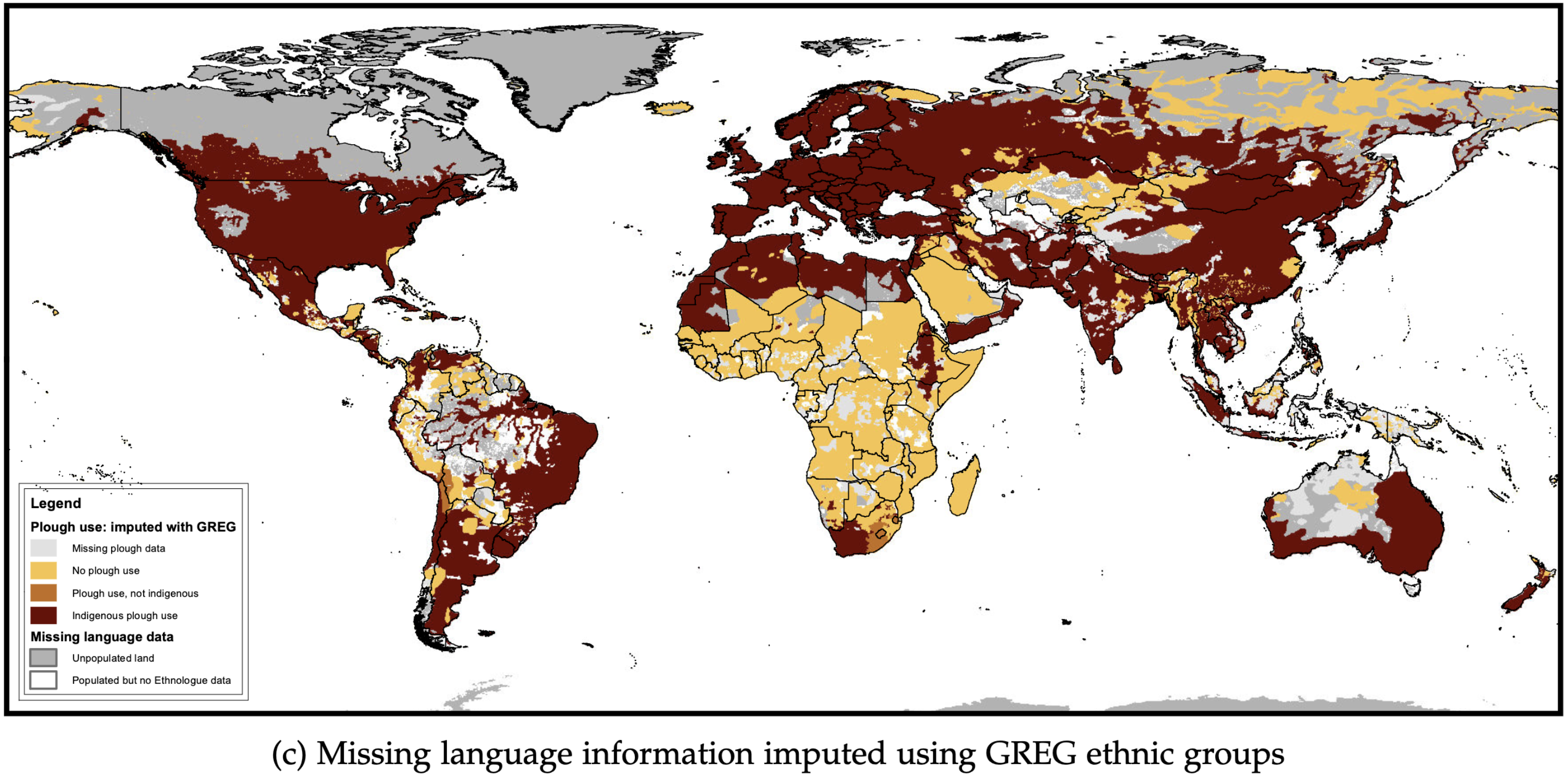

Here’s a culture map showing where in the world cultures traditionally use ploughs:

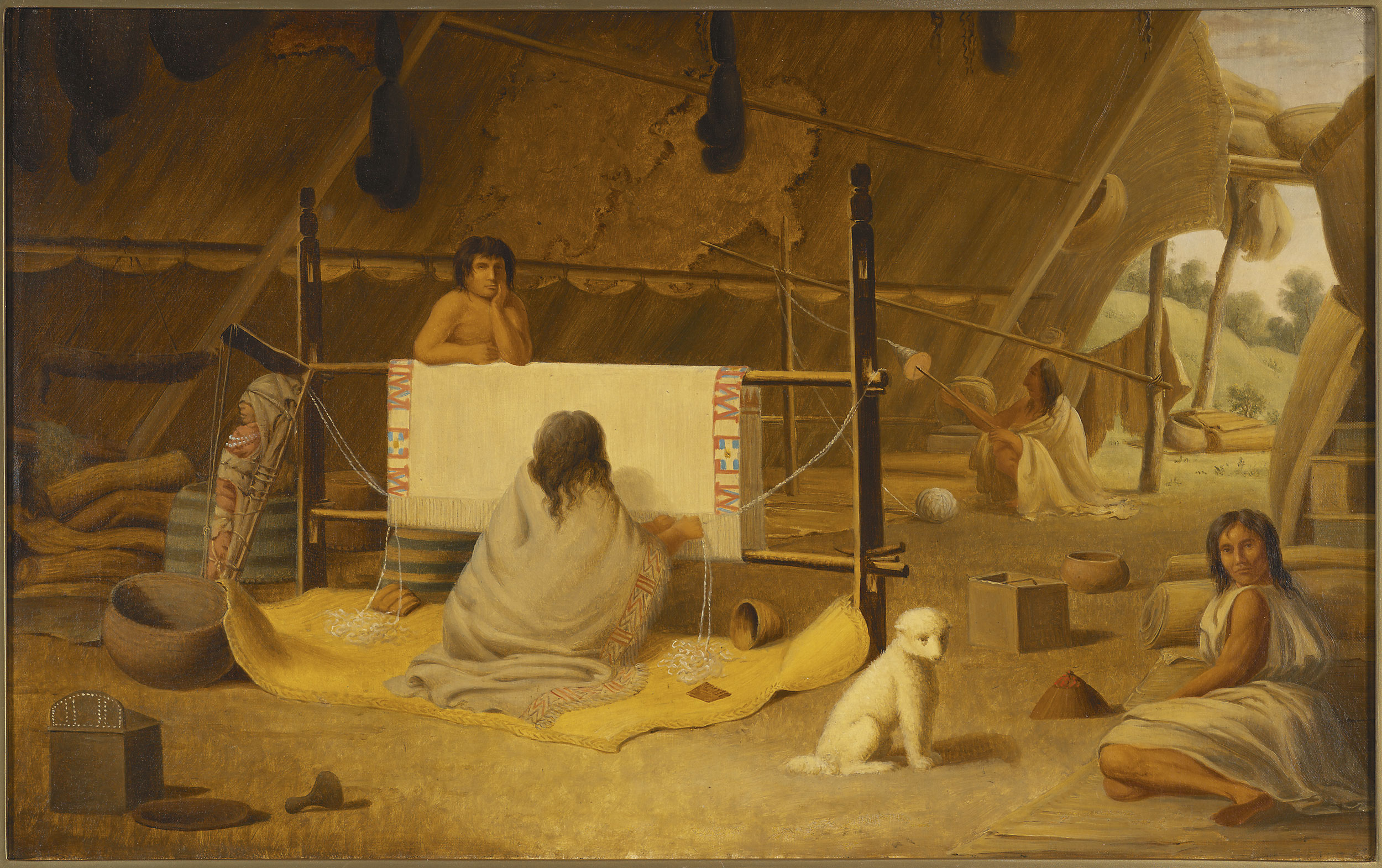

A note on plough use in North America

By some quirk of continental drift, the entire New World ended up entirely lacking in large domesticable herbivores. Cows, horses, sheep, pigs, goats, chickens, and cats are all products of the Old World, not present in the Americas before Christopher Columbus. In the New World, there were llamas, alpacas, guinea pigs, turkeys, and dogs; North America only had turkeys and dogs. Indigenous peoples of North America therefore did a lot of really creative things with different dog breeds, creating wool dogs that could be shorn and their fur woven into blankets, and plough dogs that could (kind of) pull a light plough, in addition to “normal” guarding, hunting, and sentry breeds.

Because of this imposed limitation, Animal Powers cultures in the Americas weren’t able to go full patriarchal Celestial Lights, and should therefore be expected to be somewhat more gender-equal than peoples from equivalent latitudes in the Old World, which we do see.

(When Europeans introduced horses and oxen, Native Americans knew a good thing when they saw it and readily adopted them.)

Another thing that makes the Americas different from the Old World is that many New World cultures didn’t rely on agriculture very much, continuing to hunt and forage a significant proportion of their calories until European contact. This was because humans reached the Americas last, only making it over the Bering land bridge in large numbers some twenty thousand years ago. These wanderers had a ton of room to spread out and near-infinite resources to support their small populations, so they didn’t need to do much farming. The Americas’ lack of draft animals and small, sparse human population is why indigenous societies there weren’t as technologically advanced as those in the Old World. But that’s a story for another time.

Back to the plough

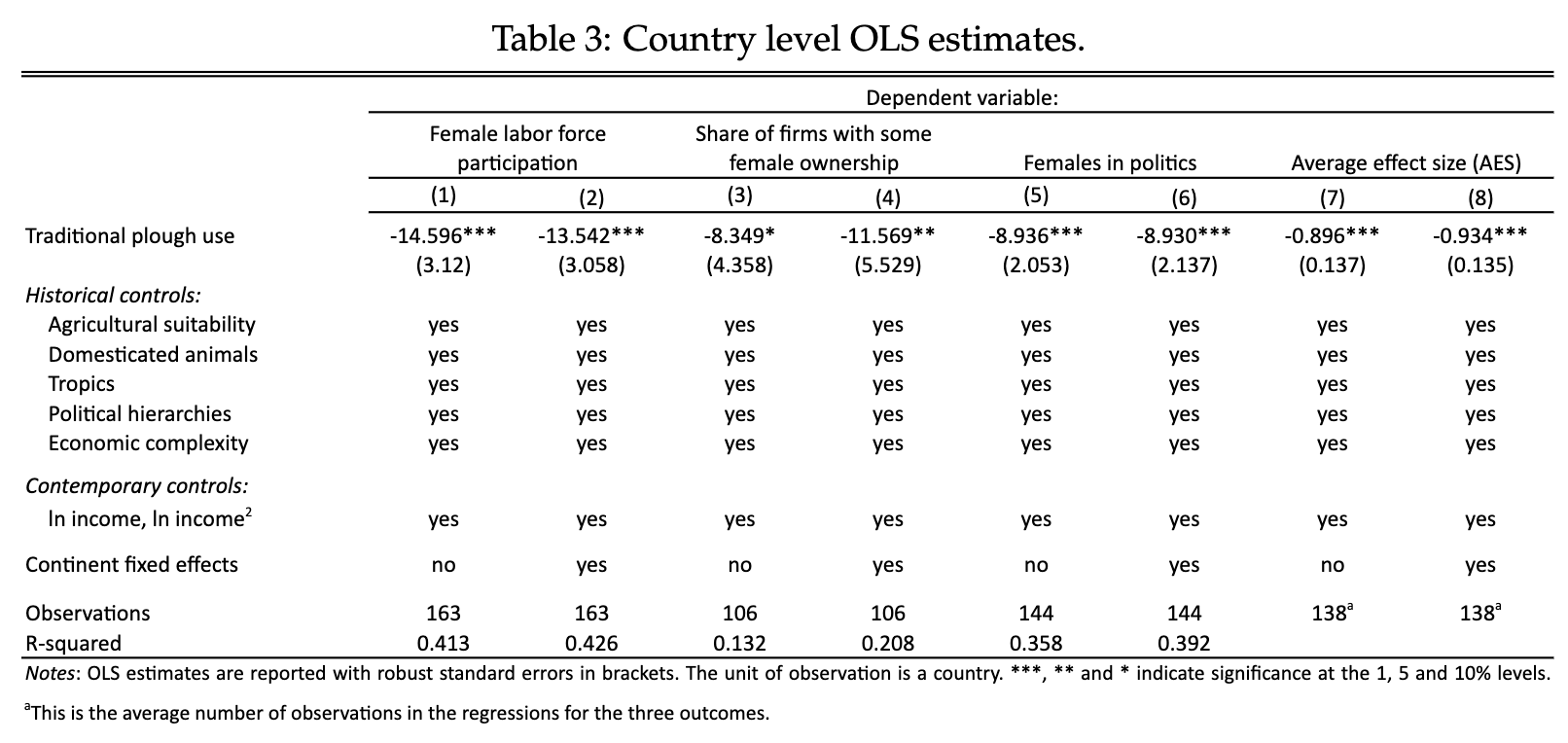

The next step in testing the hypothesis is to quantify gender equality. The paper does this in many different ways: hard statistics like percentage of women who participate in the paid labor force, proportion of businesses owned by women, and proportion of women in parliament, as well as survey results like proportion of people who agree with the statement “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” and “on the whole, men make better political leaders than women do”. The study relates each of these metrics for various societies to whether or not that society traditionally used a plough.

The results are clear. Plough-using societies have higher rates of discrimination against women by any metric, even when controlling for all kinds of potentially counfounding variables like whether that people lives in a zone suitable for agriculture, whether they had cows or horses, their economic complexity, and their political complexity.

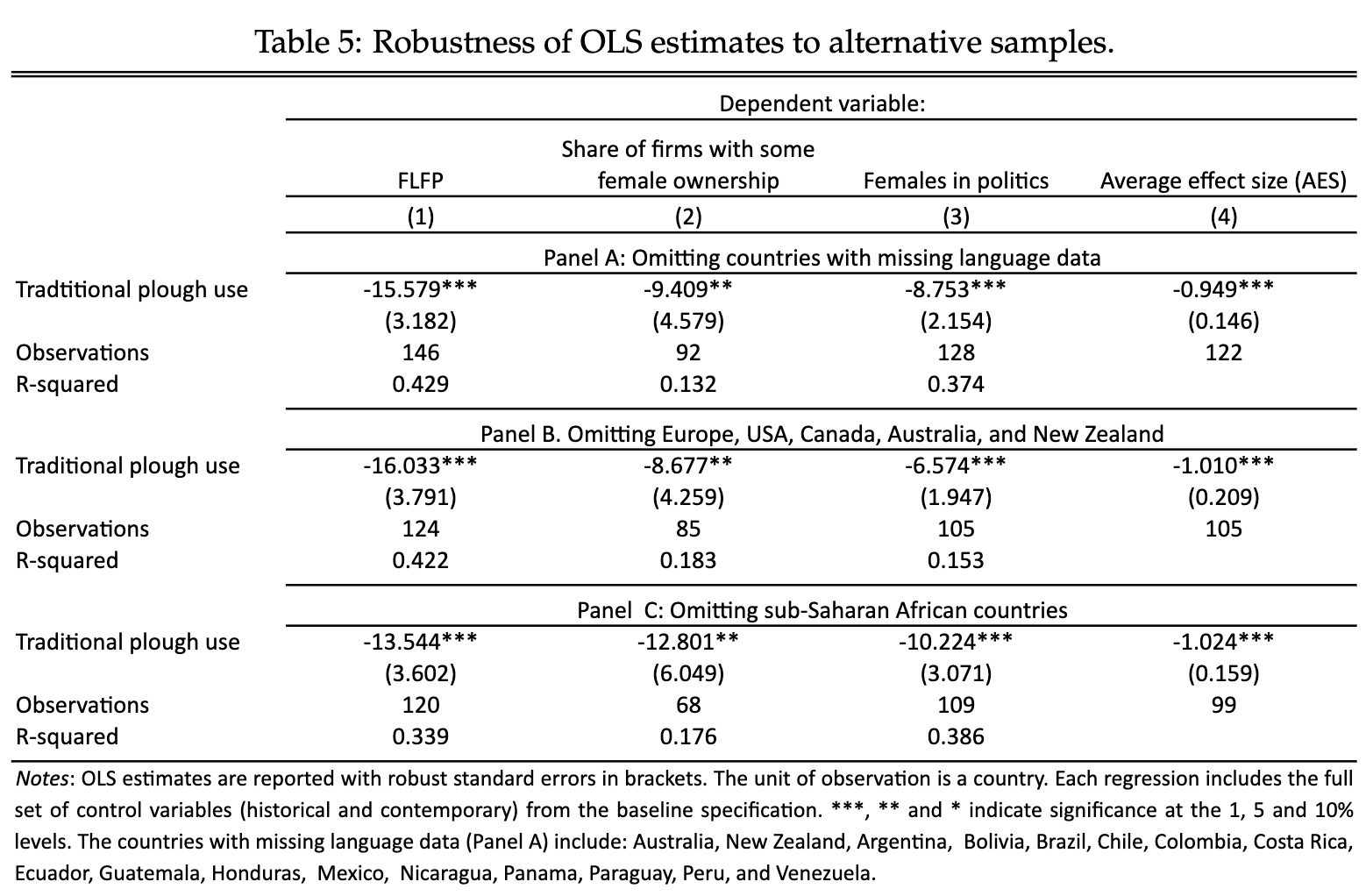

The results are also robust to removing entire regions from the dataset, such as omitting data from Europe, the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (European and neo-European countries) or omitting all sub-Saharan African countries. Let me say that another way. Regardless of if you include or don’t include any first-world countries, the trend is so strong that it still is observable in the rest of the world. Similarly, if you include or don’t include sub-equatorial Africa, which has the lion’s share of non-plough-users, the trend still holds, indicating that it’s not something special about Africa causing it.

That’s not to say plough use explains all sexism. In fact, the paper quantifies exactly how much it does explain. In two countries equal in all other respects, the non-plough-using one has on average 7.8% more women in the paid labor force, 3.1% more firms with female ownership, and 9.4% more women in parliament. While all of those values are statistically significant to the 1% level or better, none of them moves the needle by that much. Many other forces affecting these gender-equality measures are at work.

One such force is the U-shaped curve of female participation in the labor force relative to wealth in plough-using, patriarchal cultures: in very poor conditions, women have no choice but to work, and in wealthy conditions women receive educations that make them want to work, but under middling conditions men tend to be educated while women are uneducated and made to stay in the home. This function overlays the basic plough trend and weakens the plough’s predictive power in poor societies.

Conclusion

So, like a surprising number of stories in Earth history (check out Improbable Destinies by Jonathan Losos to learn how even evolution is deterministic), the rise of the white man was a foregone conclusion, a direct product of geography and climate. Human ancestors arising when and where they did–alongside spreading grasslands during the Ice Age–is another such story, as is the runaway enlargement of our brains. While coincidences and chance events like the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs sometimes dramatically shape history in unpredictable ways, a majority of the time predictable effects follow causes, and as science marches on, more and more conclusions will reveal themselves to have been foregone all along.

References

[1] Perez, C. C. (2019, March 7). Invisible Women. Random House. http://books.google.ie/books?id=MKZYDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=invisible+women:+data+bias+in+a+world+designed+for+men&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api

[2] Alesina, A. F., Giuliano, P., & Nunn, N. (2011). On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1855187

[3] Goldin, C. (1994, April). The U-Shaped Female Labor Force Function in Economic Development and Economic History. https://doi.org/10.3386/w4707

[4] Campbell, J. (1983, January 1). Historical Atlas of World Mythology. http://books.google.ie/books?id=ZToKAQAAMAAJ&q=Historical+Atlas +of+World+Mythology&dq=Historical+Atlas+of+World+Mythology&hl=&cd=3&source =gbs_api

[5] Starkweather, Katie, “A Preliminary Survey of Lesser-Known Polyandrous Societies” (2009). Nebraska Anthropologist. 50. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/50

[6] Morell, V. (2021, February 23). The Dogs That Grew Wool and the People Who Love Them. Hakai Magazine. https://hakaimagazine.com/features/the-dogs-that-grew-wool-and-the-people-who-love-them/

[7] Uberti, L.J., Douarin, E. The Feminisation U, cultural norms, and the plough. J Popul Econ 36, 5–35 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00890-5

[8] Losos, J. B. (2017, August 8). Improbable Destinies. Penguin. http://books.google.ie/books?id=1TynDQAAQBAJ&dq=improbable+destinies&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api