If you’ve ever taken an elementary-school art class, you’ve probably seen a “color wheel”:

This diagram, developed by artists and physicists in the 17th to 19th centuries, claims that the “primary” colors are red, blue, and yellow, and all other colors can be made from varying combinations of those, plus black and white. This is known as the “RYB color model”, and still forms the basis of most standard art education today. However, if you’ve actually gotten red, blue, and yellow paints and attempted to mix them to make particular shades, you’ve probably found that some simply cannot be made. Notably, when I tried this with acrylic paints, I couldn’t get purple–red plus blue in every combination made a kind of steely grayish blue. I had to go buy purple.

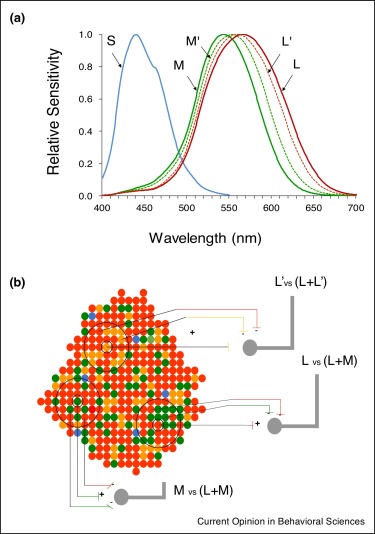

You may also have heard of the CMYK color model (cyan, magenta, yellow, and “key”, or black) in printing, and the RGB model (red, blue, green) in screens and lights. Where do these come from, and do they have more merit than the old-school RYB model?

Aside: Key

Key doesn’t necessarily have to be black; it refers to the darkest color in the printing scheme, against which the other-colored printing plates are aligned. In the risograph below, for example, which uses yellow, blue, and purple hues only, the purple was probably chosen as the key plate (since the outline of the Allosaurus is purple). In standard printer printing, though, key is always black.

This is by amazing paleoartist Greer Stothers, which I have a print of hanging in my guest bathroom.

There are three physical phenomena at play here: the way different combined wavelengths of light are perceived, the way pigments absorb certain light wavelengths, and the fact that the cone cells in our eyes are tuned to pick up certain wavelengths and not others.

Spectra

“Spectrum” means “a unit of seeing” or “a sight”. It’s the same word root as inspect, specter (a vision), circumspect (look around), introspect (look inside), spectrometer (sight-measure), et cetera. Etymologically, it doesn’t have anything to do with its commonly used other meaning, “a range” or “a variety”. That definition comes from the way that spectra are often depicted, as a range of wavelengths or colors.

Electromagnetic radiation is light, but it’s also radio, microwaves, ultraviolet (UV), x-rays, and gamma rays. It’s the form of energy carried by photons rather than by particles with mass (like alpha and beta radiation or sound waves). Since light is a wave as well, it has a wavelength, and in the visible range, short wavelengths correspond to bluer colors and long wavelengths to redder colors. Our eyes only react to wavelengths in a small slice of the total spectrum; wavelengths just longer than what humans can see are called infrared, and ones just shorter are called ultraviolet.

Notice that some colors are missing from the spectrum. There’s no pink, brown, white, gray, or black on there. That’s because these colors are how we perceive combinations of wavelengths in varying proportions.

The sun emits all visible wavelengths roughly evenly (though there’s a slight dropoff toward the blue end and subtle differences between morning, midday, and evening light due to the way the atmosphere attenuates radiation). We perceive this “full spectrum” light as being white. Subsets of the spectrum, taken together, produce other colors.

Aside: Why is the sky blue?

You’ll often hear people say that “the sky scatters blue light”. But that doesn’t mean anything; it’s just guessing the teacher’s password. It doesn’t tell you why blue rather than green or pink, and it doesn’t allow you to make any further predictions, like what color you’d expect the evening sky to be when the sunlight passes through the most atmosphere before it reaches your eye.

If you cover the sun with your hand, your hand casts a shadow over your eyes, but it’s not a pitch-black shadow. Other people can still see your eyes. That means that other light must be coming from somewhere that’s not straight from the sun. Some of that light is reflecting off objects in the environment; think of how when you put a bright orange pool floatie or similar next to a wall in bright sunlight, you notice an orange glow on the wall. That’s full-spectrum light that came from the sun; some of it (the non-orange part) was absorbed by the floatie and the orange was reflected onto the wall, and then reflected back off the wall into your eye. All objects are reflecting light all over all the time, but most of the reflection is low enough intensity that you don’t notice secondary reflections on other nearby objects.

Most of the non-direct light that illuminates the interior of shadows, though, is light reflected off the sky. Sunlight hits an air molecule somewhere in the atmosphere and reflects down and hits the shadow. Similar to the orange floatie, the air has “color” to it, or wavelengths that it preferentially absorbs, transmits without affecting, and reflects. The most common type of air molecule is diatomic nitrogen, which is about the size of the wavelength of blue visible light, so it preferentially reflects blue. This is why shadows in the daytime have a slight blue tinge, and moon-shadows at night are pitch-black, because there’s no sky-light to illuminate their interiors. Here’s a MinutePhysics video with more detail, including why the sky is red in the evening!

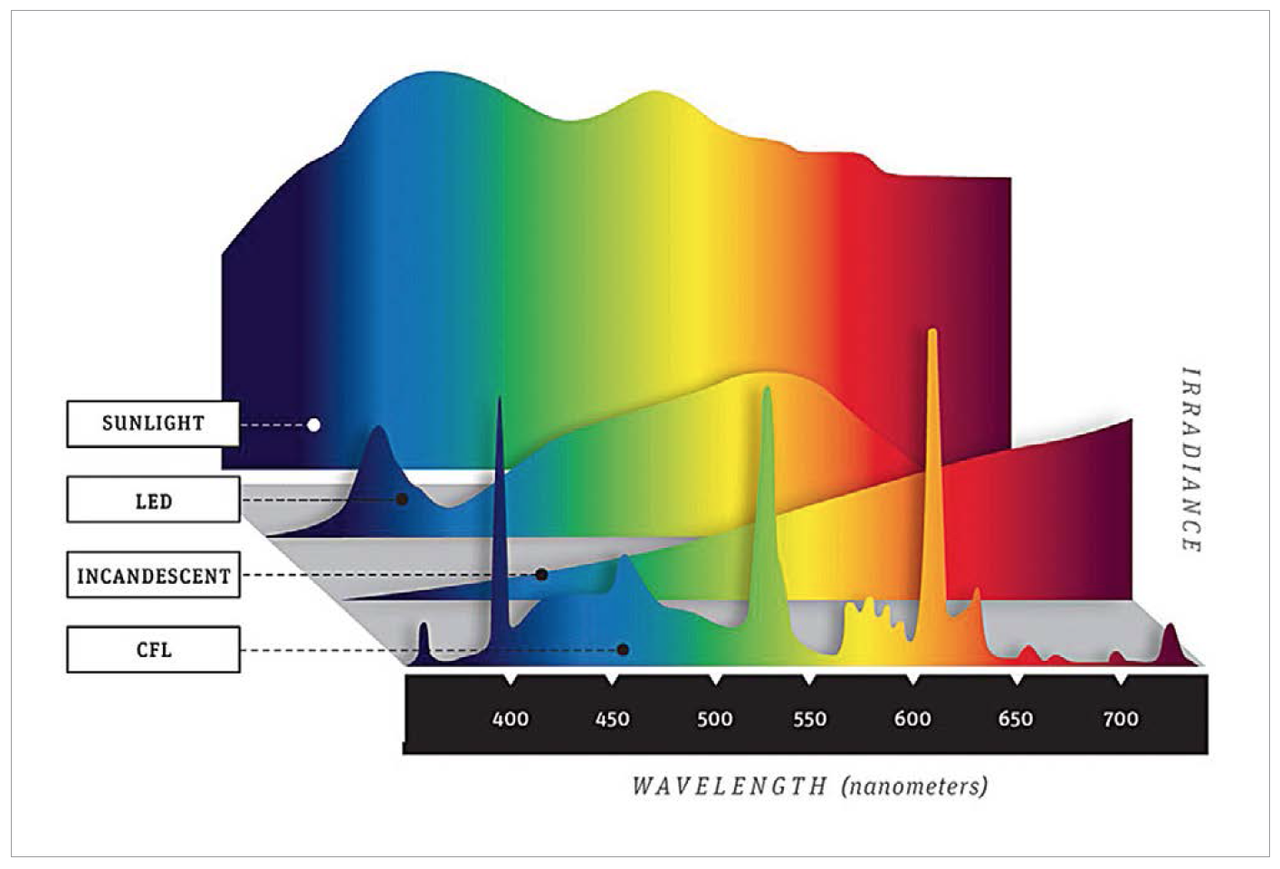

Full-spectrum light isn’t the only thing that looks white. Eyes are actually not very good at distinguishing different types of white, for reasons we’ll get into later on. Here are the spectrograms of fluorescent, phosphor-doped LED, and incandescent lightbulbs compared to sunlight:

But all of the bulbs look some shade of white. Why?

Cone cells

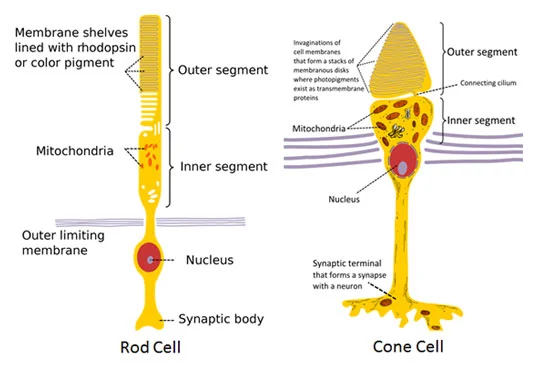

You probably already know that are two light-sensitive classes of cell in your eye, cones and rods. In humans, cones come in three types: red, green, and blue, which react only to a small band of wavelengths, providing color discrimination. Rods have a wider sensitivity bandwidth and can detect fewer photons (dimmer light) than cones, but since there’s only one type of rod, they don’t distinguish between colors, only brightnesses.

Cones and rods are both variants on neurons–as I’ve heard it put somewhere before, the eyes are pieces of the brain that popped out to say hi. And neurons, even though they’re very specialized for their function of transmitting or withholding data, are still cells that have to maintain themselves, so they still have all the cell machinery like a nucleus, mitochondria, ribosomes, and stuff. Did you know that? It shouldn’t be surprising, but for some reason I was surprised when I first learned that.

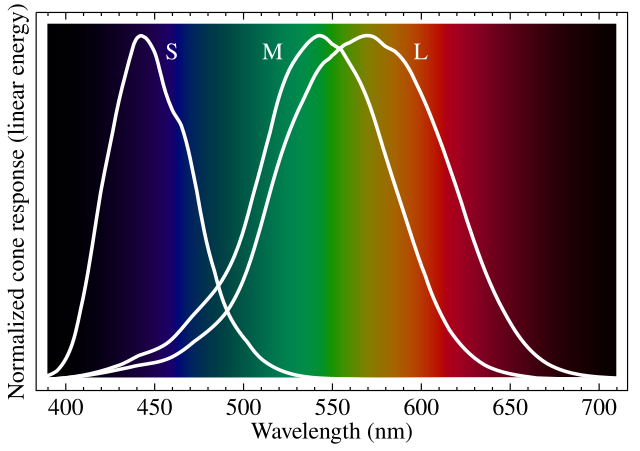

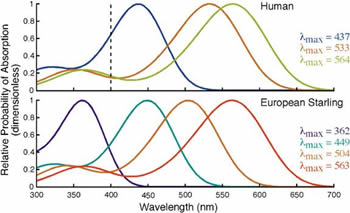

As I said before, humans have three types of cones with different sensitivity bands.

This gives us trichromatic vision (literally meaning three-color vision). L stands for long wavelengths (red), M for medium (green), and S for short (blue).

When photons of a given wavelength enter the eye, they hit all the cones and rods, but only the rods and the cones whose sensitivity bands are near enough to the photon’s wavelength will send the brain a signal that it has been activated. The other cones will remain silent. Through this, the continuous spectrum is reduced to discrete signals: either RGB (all cones are activated), RB only, R only, et cetera. The brain then interprets the different combinations and signals’ varying strengths as different colors.

Imagine you’re seeing an object that reflects wavelengths at the peaks of each of the red and green cones’ bands. You wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between that and one that reflects a wavelength in between the two peaks. You’d interpret both as greenish-yellowish (though maybe one would be more intense), because both of those objects stimulate the same sets of cells.

However, some women with a rare mutation could tell the difference between those two greenish-yellows. They’re known as tetrachromats, or four-color seers, and they have a mutated version of either the red or green cone that falls slightly in between red and green. Looking at the two greenish-yellow objects, the one that’s composed of the single wavelength would stimulate the fourth cone more strongly than either the red or green cones, and the one that’s composed of the two wavelengths would stimulate the red and green cones more strongly than the fourth cone.

Tetrachromats are always women because the red and green cone cell code is located on the X chromosome, and only women have two copies of it. In tetrachromats, one copy has the regular red or green and the other copy has the mutated one. If a man inherits his tetrachromat mother’s mutated copy, he’ll just have slightly offset trichromatic vision when compared to regular people, but probably wouldn’t be noticeable.

So why are the red, green, and fourth cones so close to each other in sensitivity, while the blue one is further away? It’s because in primates, the green cone is already a mutated version of the red cone. Most mammals only have the blue and red ones (which is why dogs are said to be colorblind). Primates are frugivores (eating fruit), so it’s important to be able to distinguish red fruit from green foliage.

The ancestral condition is actually having four cone cells. Birds, reptiles, amphibians, and many fish are tetrachromats, and their cone sensitivities are much more efficiently spaced.

During the Mesozoic (age of reptiles), mammals were mostly nocturnal or burrowing, so we lost two of our cone types. It was only after the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Mesozoic that primates regained trichromacy by modifying one of the remaining two cones. This arose in the Paleogene period, the very first time period of the Cenozoic, so it seems like it was a direct result of no longer being under the thumb of the ruling reptiles. This is why the page image is a colorful proto-mammal: it’s possible that Paleozoic synapsids like this Rubidgea would have been much more colorful than we think of mammals as being today, because they would have seen the world in four colors.

The wavelength sensitivities of our three types of cone cells is the basis for the RGB Color Model. A spectrogram with a spike at each location, red, green and blue, is perceived by humans as being white. And since these are actually the only colors humans can perceive, different groupings and proportions of these three colors can be combined to make any color humans are capable of seeing. This is how TVs work: at each pixel location there’s a tiny red, blue, and green sub-pixel, which can independently light up. If the pixel needs to display blue, only the blue one would be lit; if it needs to display pink, the red and blue would be lit together, and if it needs to display white, all three would be lit at the same time.

The hexadecimal color code system quantifies exactly how much each pixel should be lit. It’s in the format #RRGGBB, where each set of two digits controls one primary color. The lowest possible value is 00 and the highest is FF, which is the hexidecimal (base-sixteen) equivalent to 255 in decimal (base-ten). So pure red is #FF0000.

Aside: Hearing is analog, vision is digital

You can think of vision as being a digital signal, since its information comes in individual, discrete values. Audio, on the other hand, is detected by our ears using a coiled tube of variable diameter, covered on the inside with little hairs. Wherever in the tube the sound wave resonates, those hairs vibrate, and the brain interprets that as a pitch. Since it’s just one long tube, it’s a lossless signal. No data compression or quantization is happening.

Pigments

Okay, with all that out of the way, we can talk about why the color wheel is a lie.

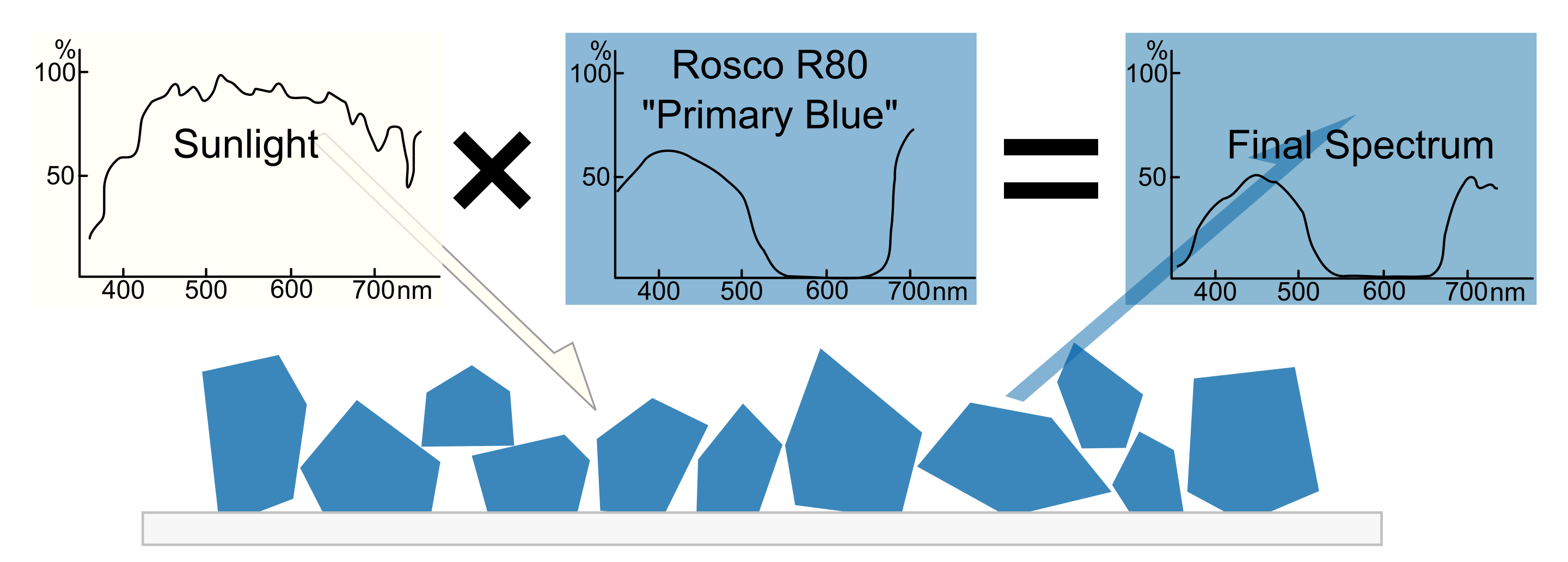

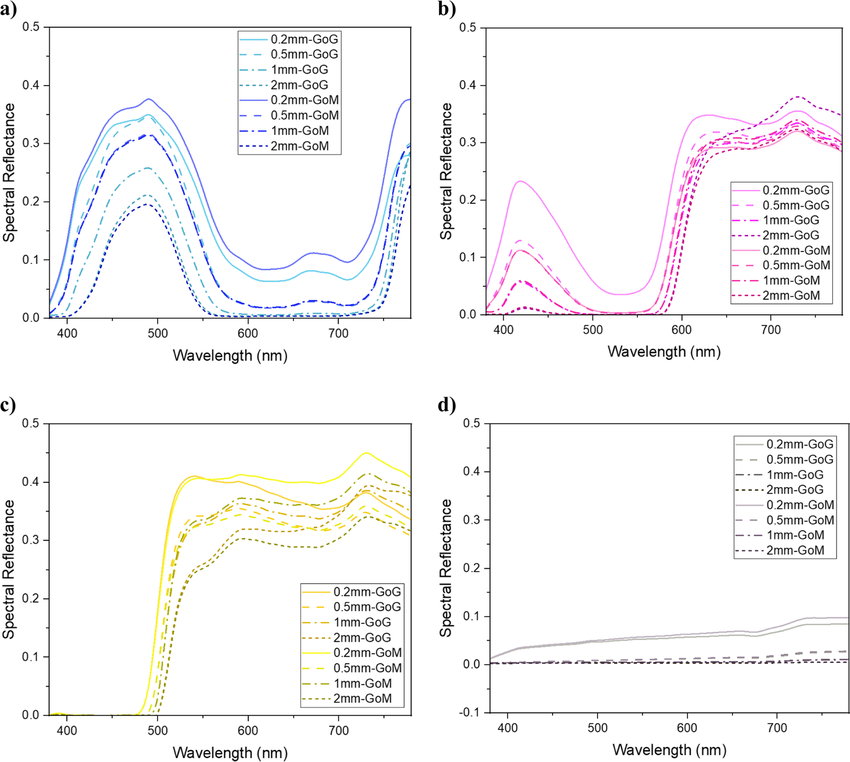

Pigments are substances that absorb certain wavelengths and reflect others, giving them a particular color. Some pigments, like Wikipedia’s example of R80 “Primary Blue”, absorb a wide band of colors and reflect only one color.

This pigment absorbs all non-blue colors and reflects only blue. But some pigments absorb a smaller subset of colors and reflect multiple colors. The standard Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow used in printing are of this type.

Cyan reflects everything except red, Magenta reflects everything except green, and Yellow reflects everything except blue.

(Blue wavelengths are the shortest, and appear on the left in these graphs, green is in the middle, and red on the right. For some reason the Cyan sample here also reflects infrared–in fact, they all do–but that’s not important for this point.)

If you mix two “everything-except” pigments, you get a pure hue of the remaining reflected color. For example, Cyan (not-red) plus Magenta (not-green) equals Blue, because that’s the only color our cones can pick up that has not been absorbed.

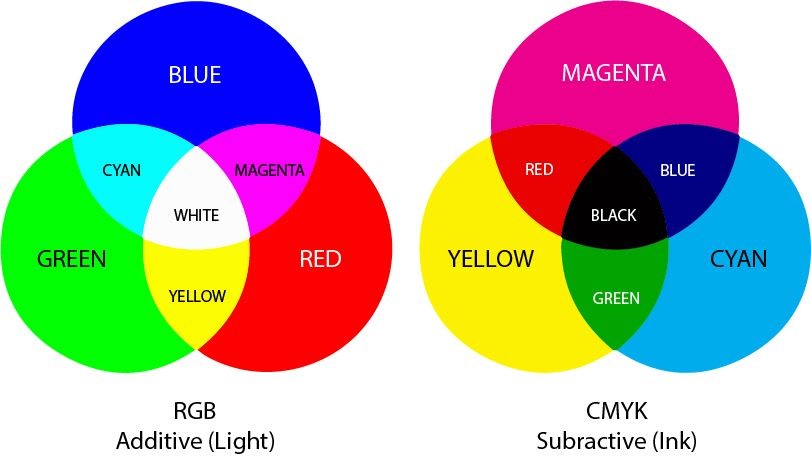

So these are the two color models: the additive, or RGB color model, and the subtractive, or CMYK color model. They’re known as such because of the different media they’re used in: if the colored thing you’re looking at emits light, like a TV, then you’re adding the wavelengths together to be perceived as a hue. If it absorbs light, like a piece of paper, then you’re subtracting away certain wavelengths to make colors.

Aside: What color are cone cells?

If a red cone cell absorbs only red, you’d expect it to appear cyan, as it reflects only the wavelengths it’s not using. But in reality, cone cells are smaller than you can see with visible light, being only 500-4000 nanometers wide. We can use electron microscopes to visualize them, but they essentially have no inherent color themselves.

In summary, CMYK and RGB are systems that are human-specific. A different animal with different cone cells would need to use different color models in their screens and paints to achieve what appears to be full-spectrum to them.

So back to the original question–where did the RBY color model come from? Well, seventeenth-century scientists and artists had no idea how eyes worked. They just experimented with mixing paints, and ended up with a model that mostly worked. Red and blue are more common colors in nature, after all, than cyan and magenta. Blood is red, the sky and water are blue; it’s hard to come up with examples of anything that’s naturally cyan or magenta. So it makes sense that people would want to believe that red and blue have some property of “primariness”. And since red and blue are close enough to magenta and cyan, the RBY color model ended up being a workable approximation of the real thing.

For further details, here’s a very in-depth Veritasium episode about color vision, including some very cute footage of jumping spiders!

Image Credits

Color wheel Allosaurus EM spectrum Lightbulbs Cones and rods Cone sensitivity Tetrachromat Bird cones R80 Blue CMY reflectance RGB Color models