Short answer: you don’t.

I’ve written about the appeal to nature fallacy before, debunking the idea that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were better off, happier, and morally superior to modern people. But I didn’t get into much detail about specifically what hunter-gatherer life was like, other than mentioning the unacceptably high levels of infant mortality. In this post, I’ll cover some things we take for granted that cavemen didn’t enjoy–as well as some things that are surprisingly ancient. People have been clever for a very long time.

Razors

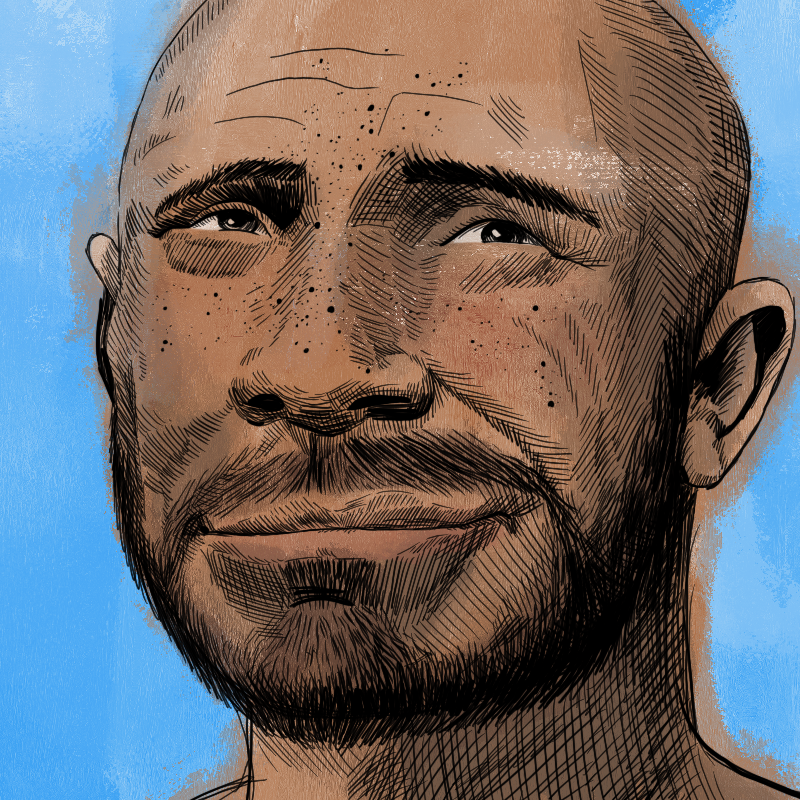

My family put on the 2002 movie Ice Age over the holidays, and I saw this depiction of Neanderthal men:

And I wondered: could Neanderthals have shaved their faces? (There are many more flagrant anachronisms present in the movie than this, mostly in the stated places and times involved–Neanderthals died out around 40,000 years ago and never expanded outside of Eurasia, while the movie is set 20,000 years ago in North America, in addition to other fauna that were neither present in that time and place nor contemporary with one another.)

Short answer: there’s no evidence for it, but it’s possible.

This was actually a really frustrating topic to research. There are tons of articles and encyclopedia entries online that claim that clamshells were used like tweezers to remove hair and that flint or obsidian were used for shaving since as early as 100,000 years ago. Additionally, they claim that clean-shaven men are depicted in cave paintings from 30,000 years ago, and that removing facial hair is helpful for preventing frostbite in sub-freezing temperatures, as condensation from the breath turns a beard into an icicle.

However, none of these sources cites a single primary source–they only circularly cite each other! As far as I was able to find, there is no evidence that pre-agricultural people removed their facial hair. The claim about clamshell tweezers was probably put forth as a tentative hypothesis about clamshells associated with other ancient human remains in some paper somewhere, and then this was picked up and repeated as if there was actually evidence for it. Furthermore, the “clean-shaven men in cave paintings” claim also has no evidence behind it that I could dig up. There are plenty of cave paintings that show human figures without beards, but this is probably artistic simplification rather than a realistic depiction. And finally, Indigenous cultures that live in snowy climates like the Inuit (North America) and the Sami (Northern Europe) do not tend to shave their beards to ward off frostbite, and there’s no evidence that shaving even helps with this, since it can also have an insulative effect. (It’s worth noting that both Indigenous groups don’t tend to grow dense facial hair, so it’s possible that the situation was different among other lineages.)

Long story short, we don’t know. I think the most likely scenario is that cavemen would’ve hacked their hair and beards shorter with flint when they got unwieldy, but not shaved close to the skin a la Ice Age. This is what I tried to show in the page image at the top: an early-thirties friendly-looking Neanderthal with a short beard, suffering from male-pattern baldness. He probably wouldn’t have looked so good from the back, as he would’ve had a tonsure-like ring of hair there.

The first concrete evidence for shaving comes from somewhere around 4000 years ago (2000 BCE), when bronze and copper straight razors are known from ancient Egypt. From then on, beards went in and out of style over the centuries, as they do now. All portraits, coinage, and busts of Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) show him as clean-shaven, and he purportedly encouraged his soldiers to do the same to prevent their beards from being grabbed in combat.

How did people even use straight razors? They had to go to a barber. In Rome, rich people had live-in servants who would shave them daily, and the lower classes would visit public barbers less frequently. Imagine how many more barbers there would’ve had to have been compared to today, when people only get haircuts once a month or less!

There were other reasons besides fashion that would’ve compelled people to remove their hair. Which brings us to…

Lice

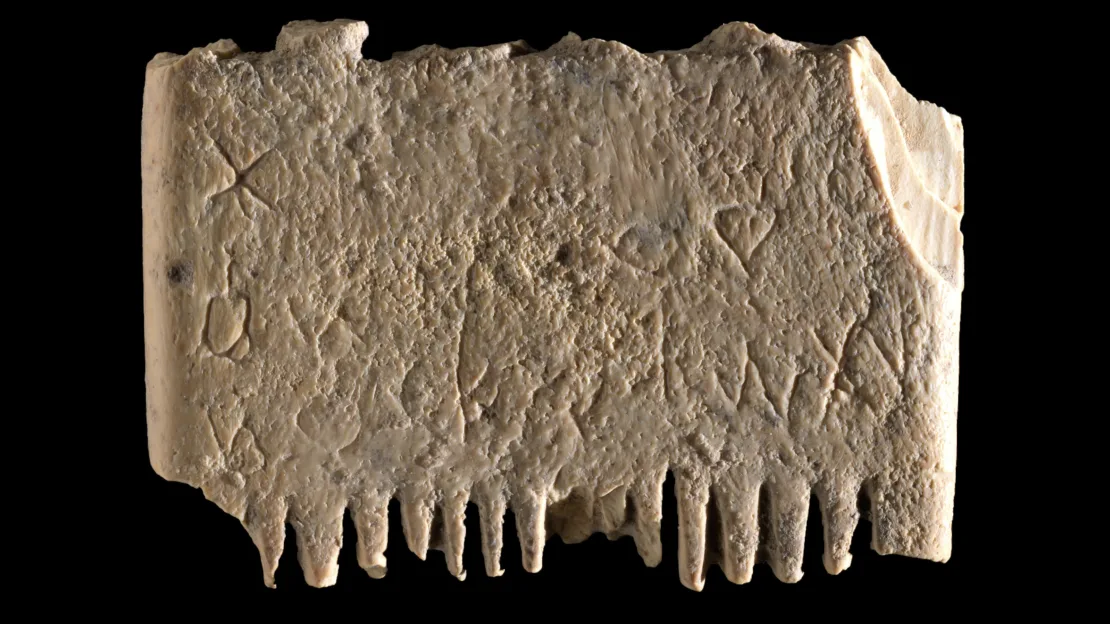

Head lice and body lice have plagued humanity since before humanity. It’s only depressingly recent–well within the last century–that we’ve been able to live mostly louse-free. Before that, the tried-and-true method of reducing (but not eradicating) the problem was using fine-toothed combs–even Cleopatra was buried with gold-handled ones. So if you were a pre-agricultural human, you definitely would’ve suffered from lice, and since fine-toothed combs are hard to manufacture, it was unlikely there was a better method than monkey-like individual picking and squashing. The oldest lice comb is an ivory one known from 3700 years ago (1700 BCE) in Israel, which also happens to bear the first known sentence written in an alphabet: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” It’s fun to imagine what the maker of this comb would think if they knew it had a special place in history. Maybe they would’ve written something more profound.

One thing that might have made lice less of a pain to cavemen than to Egyptians, however, is that soap (a combination of fat and an alkaline compound like wood ash) wouldn’t be invented until a little before 4500 years ago (2500 BCE). Extra grease and dirt on the scalp makes lice less able to reach the skin. So even a full head of lice might not have been as itchy as it would be in an era of better hygiene, and the carrying capacity on one head might have been lower due to the adverse conditions.

Oral Health

On a somewhat related note, how did cavemen brush their teeth, and did they suffer from rampant tooth decay?

The earliest preserved toothbrush is known from 5500 years ago (3500 BCE) in Egypt and was simply a stick whose end someone chewed until it was fibrous and brushy, which would’ve then been scraped around the mouth. This type of implement would’ve been very easy to invent by accident, and was therefore very likely to have been used much earlier, though being wood it wouldn’t be expected to fossilize.

On the question of tooth decay, there isn’t one answer; it would have depended heavily on diet, which would’ve depended heavily on what plants and animals were available locally. Some populations of pre-agricultural humans had minimal tooth issues, with 14% of teeth affected and many individuals having no cavities at all. But others had severe tooth decay, with over half of teeth sporting a cavity, abscess, missing crown, or being missing entirely, and 94% of individuals with at least one bad tooth. The difference came from the populations’ varying diets. Most pre-agricultural people had diets very low in sugars and starches, which would’ve made their mouths less hospitable to acidifying bacteria. But ones that had more access to fruit, wild grains, and other carbs like sweet acorns would’ve suffered from higher levels of dental problems. But on average, pre-agricultural humans would’ve had better teeth than early agricultural humans.

Pre-agricultural humans also would’ve had straighter teeth than their early post-agricultural descendants. After the invention of agriculture, humans underwent a suite of minor physical changes that were a result of living shoulder-to-shoulder and working nine to five. Humans who were better at getting along with others and staying on a single task for long periods of time would’ve been more successful. These are essentially the same qualities we select for when domesticating animals, and in mammals, there are certain unrelated traits that go along with domestication, known as domestication syndrome: floppy ears, curly tails, short faces, brains smaller by 3-4%. Dogs, pigs, sheep, and alpacas all display these same characteristics, and while humans don’t have tails or long ears, we do exhibit the other elements of the syndrome, short faces and reduced brains. (It’s not fully understood what was in the 3-4% that was lost, but probably a lot of it was related to constant vigilance.) In humans, a shortened face means a reduced jaw, which means less room for the same teeth. Cavemen wouldn’t have had the same issues with impacted wisdom teeth that we face now.

So this is one in which cavemen might not have had it so bad. Early post-agricultural humans would also have had varying levels of tooth decay depending on the local diet, but generally had much worse oral health than those who came before. It was common for people to have no teeth left by their late thirties, and dentures wouldn’t be invented until around 700 BCE.

Glasses

Another technology we take for granted these days is optically clear glass. Basically everyone needs glasses at some point in their lives due to the way human lenses age (old cells get crammed toward the center and never resorbed, causing stiffness to increase with age). But until quite recently, this was not an option; people would’ve had to get by by squinting or asking youngsters to do things for them.

The earliest predecessor to glasses was known as a reading stone, a convex optically clear gem or piece of glass that would be placed on top of text to magnify it. Nero (54-68 CE) was said to have used an emerald for this purpose, but the practice didn’t become widespread until the middle ages.

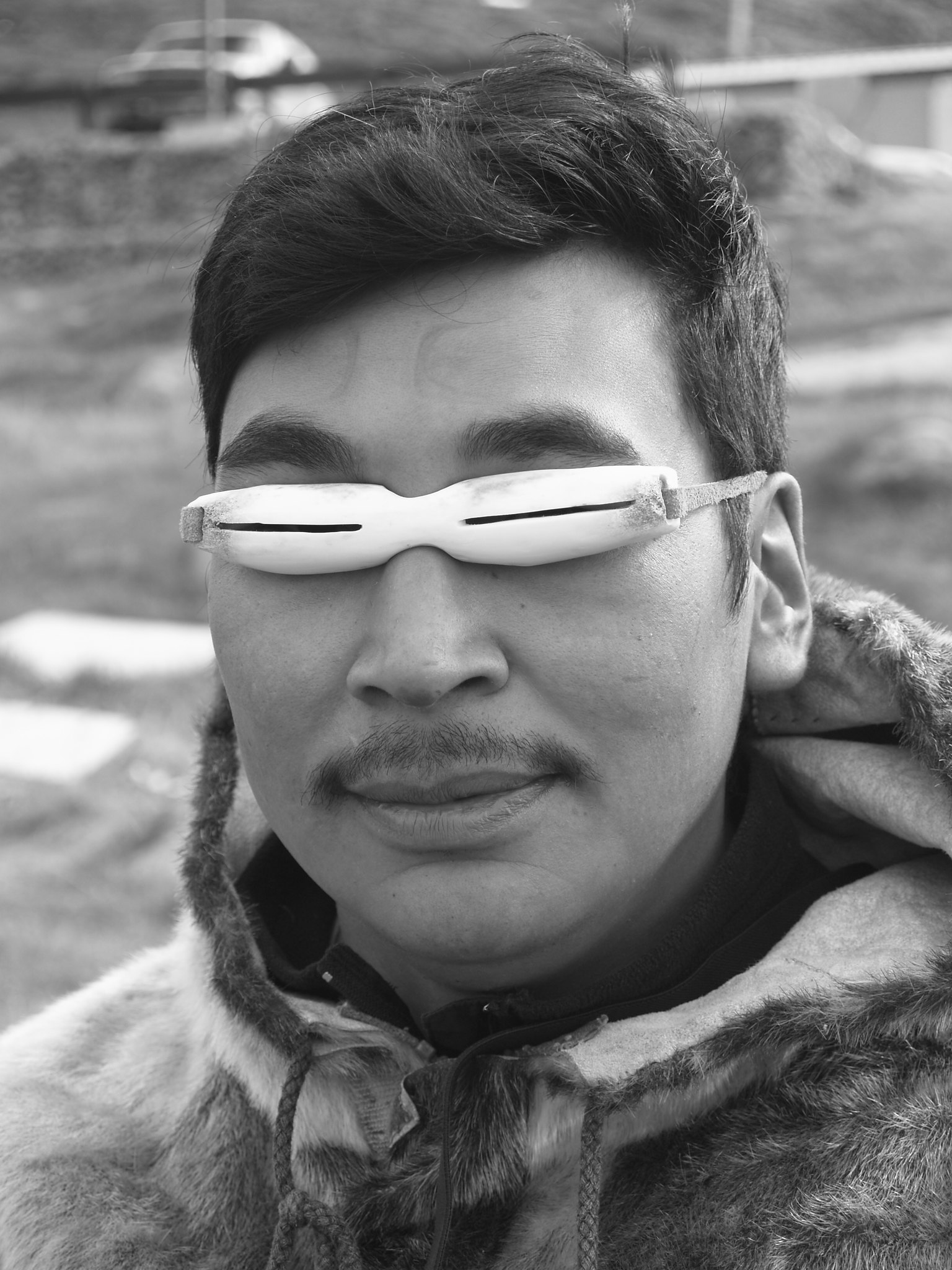

However, there was one much earlier vision-correcting and vision-protecting technology that might have been accessible to pre-agricultural humans: snow goggles.

This opaque eyewear had a single horizontal slit over each eye, and was painted black on the inside to reduce glare. The main function was to prevent snow-blindness, or sunburn of the retinas common in sunny, snowy conditions, but increased visual acuity due to the focusing nature of the slit was a nice side-effect, like a pinhole camera. In tree-poor tundra and steppe environments, these were made from animal bone with straps of hide. Their earliest known use is from 500 CE North America, so it’s possible that cavemen would simply have squinted, but it’s also possible that we just haven’t found an early example.

Ice

Speaking of cold conditions, did ancient people have access to ice and refrigeration?

Short answer: only if it was freezing out. If not, they would have preserved food through smoking, drying, or salting. But there are some interesting technologies early post-agricultural people used for icemaking and refrigeration that are worth discussing.

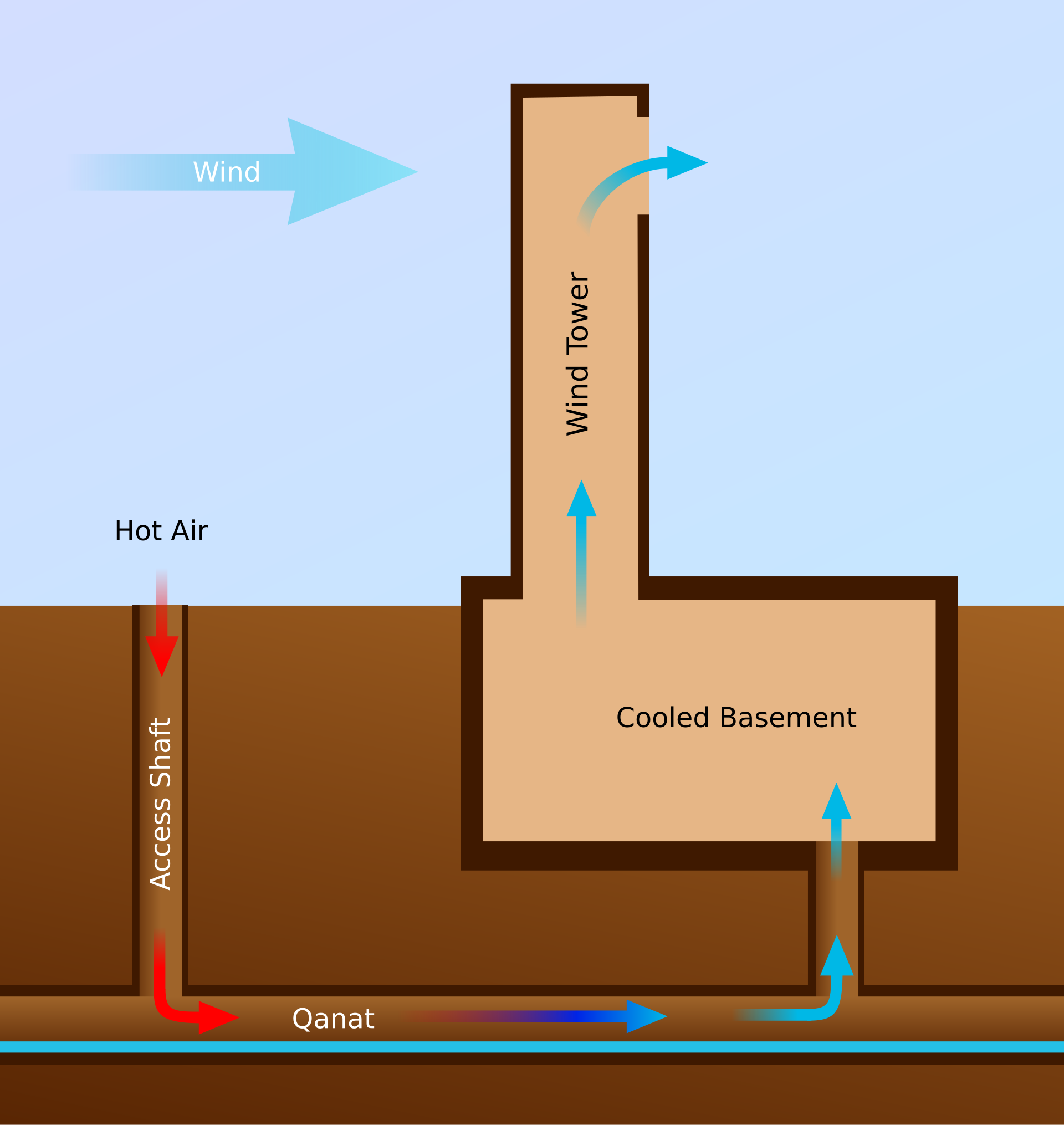

In Iran around 3800 years ago (1780 BCE), they built domelike structures called yakchāl, which took advantage of the arid environment to refrigerate a basement through evaporative cooling.

The effectiveness of these structures was boosted by the use of shade walls to keep out direct sunlight. But they didn’t tend to get cold enough to actually freeze water. However, a simple shallow pool of water with an insulated bottom surrounded by shade walls would freeze overnight in the desert due to the evaporative and radiative cooling shedding more heat than could be conducted from the ground below. This ice would’ve then been harvested and placed in the yakchāl, and used for making frozen desserts like sorbet.

The image of people harvesting ice from northern lakes and transporting it to warmer climes, known as the ice trade, only occurred for about a century between the spread of railroads and the invention of the refrigerator, from 1806 to 1914.

Clothes

PBS Eons has a good episode on how we can tell when people started wearing clothes, and our estimates are somewhere between 171 and 83 thousand years ago, based on the estimated time of genetic divergence between body lice and head lice. But the clothes themselves don’t tend to preserve, being made of soft stuff. What did cavemen wear?

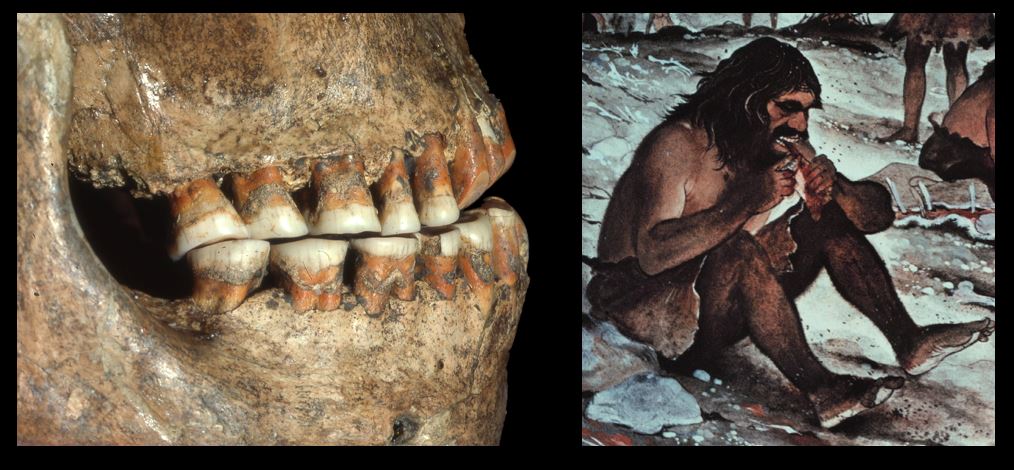

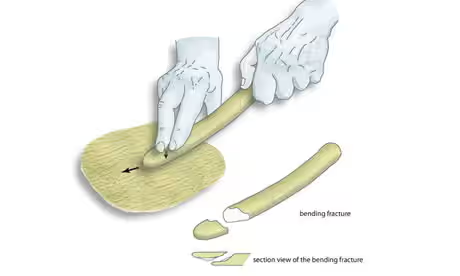

We have evidence from multiple sources that they processed hides, and while we don’t know exactly what they were used for (sacks and shelter are other potential use cases), clothes are certainly an obvious candidate. Severe grinding down of the front teeth is common in both early modern humans and our closest relatives the Neanderthals, and the micro-wear indicates that they were using their mouths to hold and stretch skins with one hand while using a tool in the other to scrape or cut it.

Micro-wear on stone tools also suggests some of them were being used for hide scraping, and cut marks on carnivore bones look like their skins were removed. We also have found quantities of a leatherworking tool known as a lissoir made from deer ribs in both Neanderthal and human assemblages, and we even have preserved residue of tannins, the chemicals used to turn rawhide into leather, on stone tools associated with Neanderthals.

While no sewing needles are known from Neanderthal assemblages, ancient humans used them as early as 61,000 years ago, and a 50,000-year-old needle is attributed to the enigmatic Denisovans, so it’s possible that Neanderthals also used needles and we just haven’t found them yet.

So they wore hide and leather garments, and may have sewn them together. How much work was that?

To process the approximately five large animal hides that went into a full outfit for one person using archaic methods would’ve taken a minimum of 20 hours, but probably closer to 80. This outfit would’ve needed to be replaced every couple years at least, and that’s not even including all the other necessities made from hide such as backpacks, sleeping bags, and tent fabric. Hide working certainly accounted for a big chunk of labor in a hunter-gatherer’s life.

Miscellaneous

Pre-domestication, a lot of fruits and vegetables were really underwhelming. An ancient human biting into a slice of watermelon would’ve found their mouth full of huge black seeds and white pulp, and just a tiny amount of red flesh. (Watermelons stayed like this until the 1700s!)

And to collect enough corn to make one modern cob’s worth would’ve required visiting many teosinte plants.

Here’s why eggplant is called that:

(Even the wild version does eventually ripen to a deep purple, but for awhile during development it really looks like the plant is laying eggs.)

And one last note about infant mortality. In the Stone Age, approximately one in sixteen mothers would’ve died in childbirth, and a mother could expect to lose at least one child during her life. Like tooth decay, mortality from birth got worse before it got better: in seventeenth-century French hospitals, one in two women died due to misguided medical interventions such as bleeding that made things worse.

Conclusion

In all, life was indeed a lot nastier, more brutish, and shorter during the Stone Age. While hunter-gatherers may have only had to hunt and gather three to five hours a day to sustain themselves, they sustained grievous hunting injuries and bodily wear from repetitive manual labor, and would have spent hours outside of food procurement working hides, making and repairing tools, and walking to new places. In some ways they were better off than the early post-agricultural humans of 10,000 years ago, such as in dental health and potentially severity of lice infestations. But compared to the modern day, it’s no contest. I don’t want to be a caveman–do you?

References

Ancient Egyptian razor Alexander the Great Snow goggles Ice house Neanderthal model Lice Fruit Tooth decay Tooth wear Lissoirs Scrapers