Here’s Part 2 of the Royal Tyrrell Museum review, going through their chronological deep time exhibit. If you haven’t yet read Part 1, go check it out!

Ediacaran and Cambrian

Most paleontology museums I’ve visited organize themselves in this manner, giving the viewer a tour through deep time, starting with the earliest visible life. It’s often challenging to make the early stuff as engaging as the dinosaurs, because the life-forms were so small and alien-looking and the fossils aren’t as well-preserved. Let’s see how the Royal Tyrrell stacks up!

That stromatolite that it encourages you to touch is the real thing, and it’s 1.8 billion years old, from right at the beginning of the Boring Billion! Pretty cool you’re allowed to touch something that ancient.

Mistaken Point, Newfoundland, Canada, is a very famous fossil site that preserves pre-Cambrian animals. This slab contains dozens of visible impressions of Fractofusus and other members of the Canadian Ediacaran biota, 575 to 560 million years ago. A very cool specimen that reminds the viewer that dinosaurs aren’t the only fossil organisms Canada’s famous for. I also like the enlarged models of the organisms that help people draw the connection between what they see on the slab to what the animal would’ve looked like in life.

Moving into the Phanerozoic, Canada is also the home of the famous Burgess Shale, the best place in the world for finding abundant Cambrian animals. However, most of the important ones are super tiny. To deal with that, the museum put original specimens under magnifying glasses, and supplemented them with more enlarged models and drawings. Viewing the real Pikaia like this is like visiting your great-times-a-billion-grandfather’s grave. Amazing!

Here are a few Cambrian fossils large enough to see without a magnifying glass. I think overall the explanations are very well done, and the variety of specimens covering so many families is impressive.

When leaving the Cambrian exhibit and moving forward in time, there was a big room with a 3D, enlarged diorama showing a Cambrian environment with models of the animals whose fossils we’d just seen engaged in various life behaviors. The display lit up different animals at different times to draw attention to one part of the scene or another, and extended underfoot as well as behind glass as if at an aquarium. It was so dang dark in there I couldn’t really get a good picture, but it was a pretty neat diorama.

Overall, the Ediacaran and Cambrian exhibit is a 10 out of 10.

Ordovician to Devonian

The more recent the fossil, the better-preserved, more recognizable, and generally bigger they are. While the Royal Tyrrell’s Ediacaran and Cambrian collection is nothing to sneeze at, we see some even more exquisite and impressive specimens as we continue through geologic time.

Look how many there are! And they’re all roly-poly! Trilobites arose in the Cambrian and persisted through the entire Paleozoic, going extinct after a reign of almost 300 million years in the Great Dying at the end of the Permian, but their greatest diversity occurred in the Devonian, or the Age of Fishes. They ranged from the size of a grain of salt to a coffee table, and many of the later ones had ridiculous spikes and frills all over, like this beautifully-preserved Comura that appears to have cartoon eyelashes like a car in a Chevron commercial.

Here’s another big group of armored critters, but this time they’re fish! Mass fish deaths like this occur when their pond dries up or is demolished by a nearby landslide.

The next area grouped invertebrate fossils by phylum, in order to give the viewer an idea of who’s related to whom. Again, the fact that they have enough of a collection to not only represent every phylum within this temporal range, but to show multiple representative examples of different members within each, is very impressive. Highlights include another cluster of adorable trilobites and a couple of highly detailed three-dimensional crinoids. (The two cut-off phyla are bryozoans and sponges.)

There was also a broken-out section just for corals and other reef-builders, which I thought was a nice touch, since most people associate “reef” only with “coral”. Super minor nitpick about the extra comma before “calcareous algae”.

As we progress through the Age of Fishes, vertebrates (which are all in the same phylum–you are more closely related to a fish than a clam is to a brachiopod) diversify into a few different important fish families, which are displayed next.

While it’s super cool to see a real specimen of Eusthenopteron (visiting great-times-a-million-grandfather’s grave again), this definition of rhipidistian isn’t quite right, as that clade is now understood to contain lungfish and tetrapods, with coelacanths as an outgroup. And saying that “sarcopterygians have two dorsal fins” isn’t really accurate either, since I’m a sarcopterygian and have zero dorsal fins. But I’m nitpicking again.

I really like the triplicate depiction of Eastmanosteus here. The diagram shows where in the body the armor fits, but the model accurately shows the armor as being hidden by skin. A lot of placoderm paleoart mistakenly slaps the armor on the outside.

And no exhibit of placoderms is complete without ol’ Dunk. Here he is. I think this is the second specimen I’ve seen, the first having been in the ocean exhibit at the Smithsonian. How many Dunks I can rack up in my lifetime?

There were also sections for actinopterygii (ray-finned fish), chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish), and acanthodii (spiny sharks, an extinct group that may turn out to be a paraphyletic grade), but since the fossils on display were all casts, I didn’t take pictures of them. The info was good though, and it makes sense to include them for completeness even if the museum doesn’t own originals of every relevant clade.

Just before leaving the Devonian was this diorama of an early amphibian, which was labeled Ichthyostega.

Not only is this animal fairly shrink-wrapped, lacking webbing on its hands and feet and fins or patagia on its tail and between limbs and body, it also has the wrong number of digits. Ichthyostega had six on its hind feet (unknown on its front feet, so the museum gets a pass there). Here’s a better depiction of Ichthyostega:

Overall, 8 out of 10. Great exhibit, but it would be even cooler if all the specimens were originals, and I docked one more for the missing toe.

Carboniferous and Permian

Moving onto land, we have some bug-forward displays showing the diversity of the Carboniferous, or Age of Insects. However–what’s this? Some of these specimens are Cretaceous, others Eocene, still others modern?

While I get what they’re trying to say here, that these insect families originated in the Carboniferous, the inclusion of insects from all over geologic time is kind of misleading.

This big slab that was once traversed by a disturbing number of millipedes is pretty cool. Imagine all their toothbrushy legs undulating… bleh.

There was also a Carboniferous diorama, showing the charismatic big bugs Meganeura (a crow-sized dragonfly relative) and Arthropleura (a log-sized millipede) frolicking among the Lepidodendron (scale trees). I missed getting a photo, but it was decent; then again, it’s hard to do a Carboniferous scene wrong, given that the bugs look just like giant versions of their modern relatives and fossils of scale trees look exactly as the trees would’ve looked in life.

The first thing in the Permian area was a wall covered in slabs with preserved temnospondyls (giant amphibians) and reptiliomorphs (transitional forms between amphibians and reptiles/mammals). I like the attention paid to each obscure tetrapod, highlighting the diversity of forms and lifestyles even back at the beginning of life on land.

Those two were the coolest originals, and generally I’m skipping over the many casts that were also on display. But I wanted to complain about this one:

I think it would be better to explain diapsids as including all modern reptiles, but that there used to be other reptiles that weren’t diapsids, rather than the detail about the holes behind the eye, which no non-paleontologist cares about. Saying “the most famous diapsids were dinosaurs” is weirdly subjective. Are non-avian dinosaurs really more famous than snakes, ducks, or turtles, which every two-year-old has heard of? I don’t think so. And lastly, not including birds as an example of modern diapsids is a miss.

These little Trimerorhachis amphibians were also a victim of a drying pond. You can really imagine how they would’ve looked in life. This specimen is the one that I did a plaster cast of at the end of the day!

My cast! This is now on my bookshelf. While the casting workshop was aimed at kids, the teacher was quite knowledgeable (and impressively graceful at fielding nonsensical child-questions) and I had a good time :)

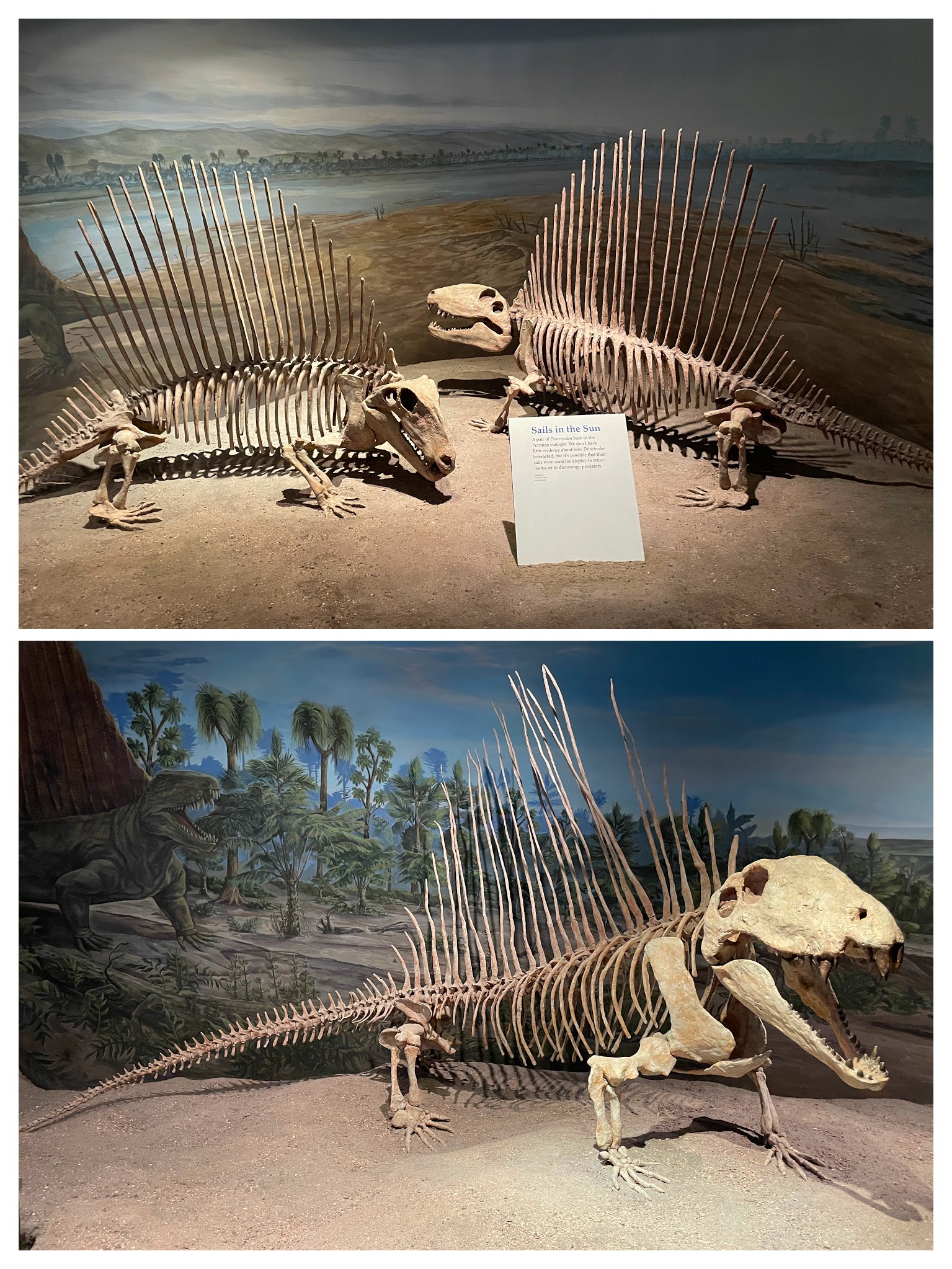

I think Eryops and Dimetrodon might be the specimens I’ve seen the most. I think literally every museum I’ve reviewed so far has these guys. And no wonder–look how big and thicc those skulls are. If a modern bird skull is an iPhone 16, these things are those indestructible Nokias.

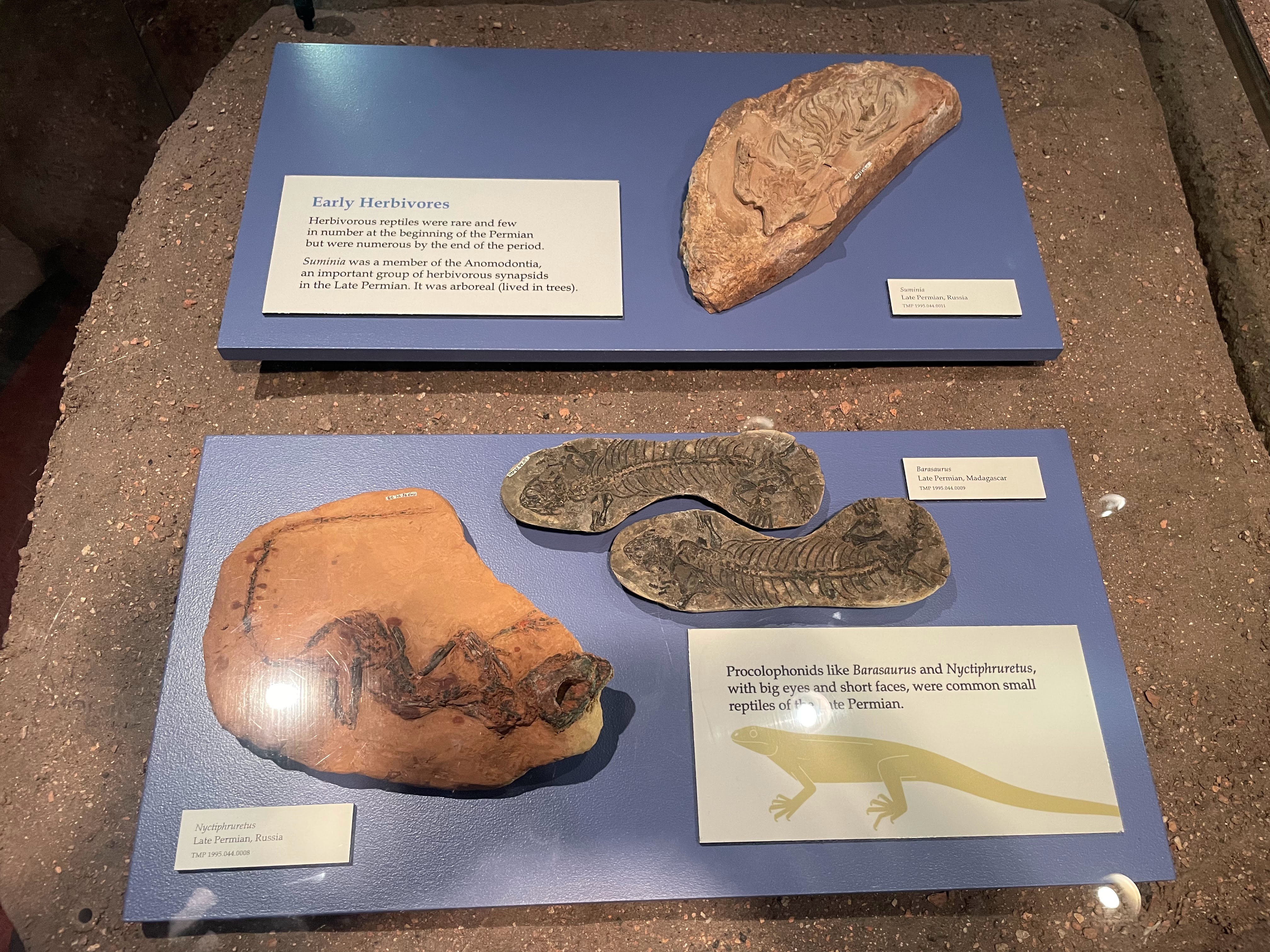

These little herbivores, I’d never seen before, and hadn’t even heard of, which makes it a cool display in my book. However, I wish they’d included a drawing of Suminia the way they did of the reptile below it, because the fossil is so jumbled up it makes it hard to imagine. I also wish they’d noted that Anomodontia includes the famous dicynodonts, and that they were stem-mammals. Those seem like critical things to leave out.

Overall, 7 out of 10, for some misleading or incomplete signage. Come on, Tyrrell, such a strong start! Let’s keep up the momentum!

The One Triassic Specimen and the “Cretaceous Garden”

The Triassic room was entirely taken up by a single specimen of Shonisaurus, a sperm whale-sized ichthyosaur.

There were lots of inspirational quotes on the walls by Betsy Nicholls, the late paleontologist based out of the Royal Tyrrell who led the excavation of the specimen. I like the tribute paid to the hometown hero, and the specimen itself is ridiculously huge and complete, definitely a bucket-list fossil. But really, nothing else from the Triassic, my favorite geologic period? Not even one Coelophysis?

Another odd thing about this room was the “Cretaceous Garden” that teed off of here. This was probably just a quirk of architecture, that it didn’t make sense to put an exit to the courtyard somewhere in the actual Cretaceous hall. But it was a bit confusing.

Also somewhat unfortunately, this garden was very much not Cretaceous. I’m no botanist, but a vast majority of the plants in here were angiosperms, or flowering plants. During the Cretaceous, angiosperms existed, but represented a minority of the diversity of plant life; ferns, conifers, and cycads would have made up most of the foliage. There was one pretty cool Cretaceous petrified tree trunk of Metasequoia, or dawn redwood, a genus that arose in the Late Cretaceous, right next to a modern sapling of the same genus, which was a clever touch.

Shonisaurus plus garden, 6 out of 10, mostly propped up by the sheer impressiveness of the one specimen.

Straight into the Jurassic

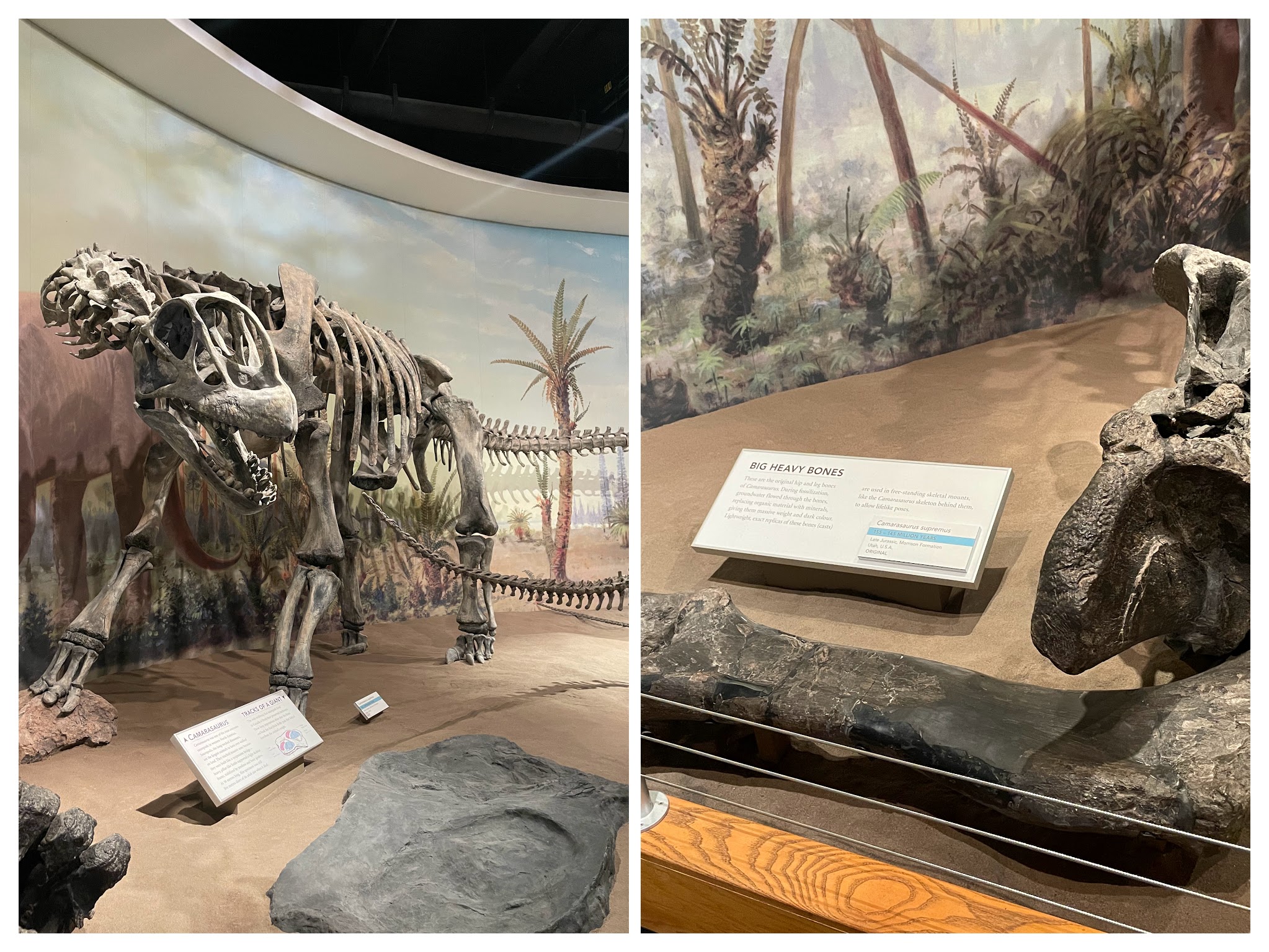

Leaving the hall of Shonisaurus, we enter the main HALL OF DINOSAURS! The first thing you see is the one and only sauropod in the museum, Camarasaurus.

Similarly to the Black Beauty Tyrannosaurus, some of this specimen’s bones were too heavy to mount, but the museum lets you look at them anyway. Nice!

Here’s Allosaurus demolishing Camptosaurus while two Ornitholestes hang around, in front of a mural depicting the same thing. I think posing the skeletons in the same way as the art is a neat gimmick. However, the mural is pretty outdated, and was outdated even when it was painted, when the museum opened in 1985. In this case it’s not so bad, and the anatomy of all three dino types is accurate. But on the other hand…

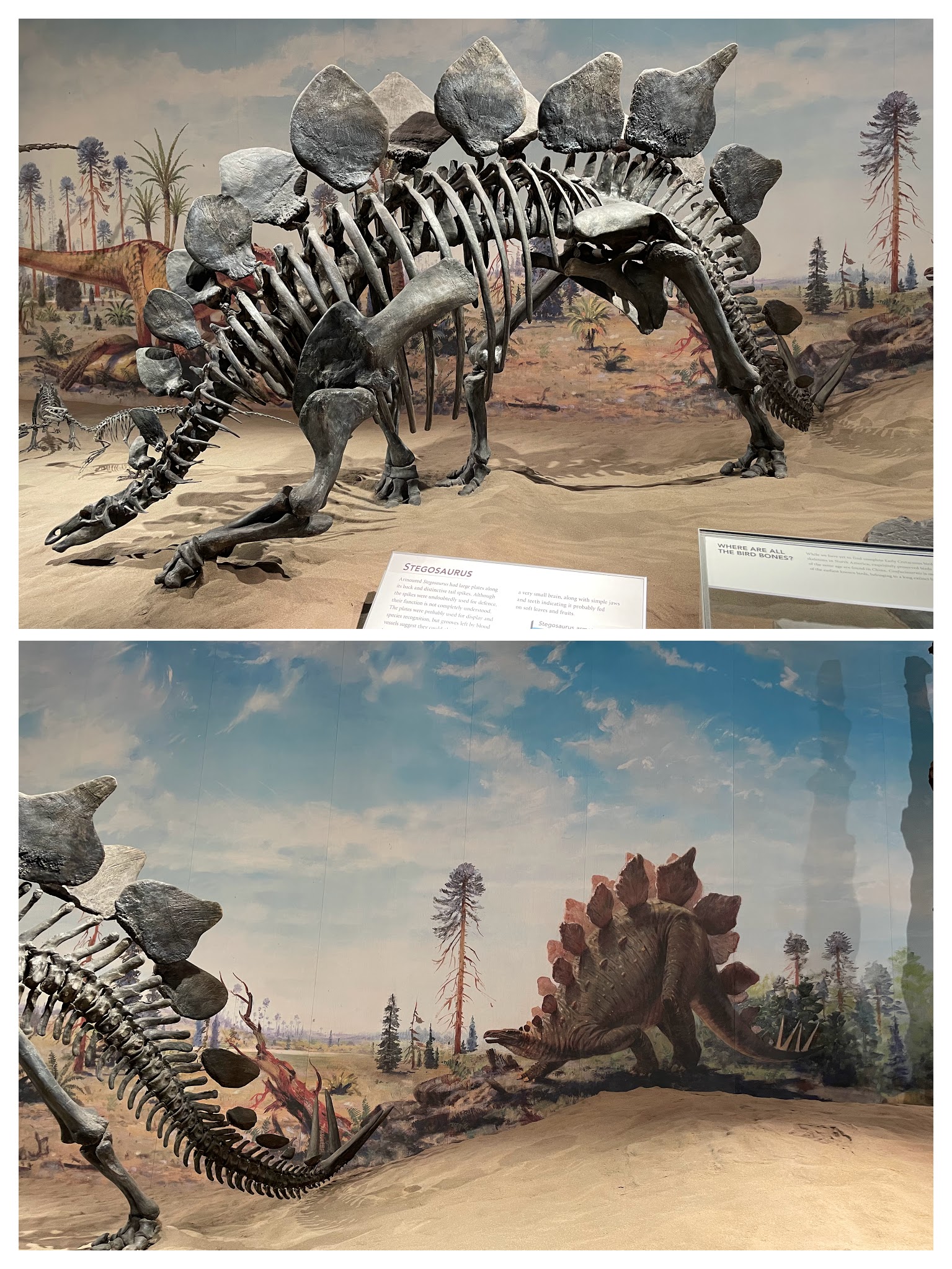

What is going on here? This has to be the weirdest Stegosaurus mount I’ve ever seen. Why are its hind legs so hyperextended? Why is its nose an inch from the ground? This “Gateway Arch” look was popular pre-Dinosaur Renaissance (the museum’s inauguration was just one year before the publication of The Dinosaur Heresies, so maybe they deserve a pass), but even back then most didn’t take the drooping head and tail to this extreme. Does any modern animal hold its head like this? No?

7 out of 10 for the Jurassic.

Cretaceous Hall

Now for Alberta’s bread and butter, the geologic period whose remains you find when you walk around outside the museum: the Cretaceous! This hall was by far the most impressive and extensive of the sections of the geologic time scale. Like I said before… more ceratopsian and hadrosaur skulls than they know what to do with!

Here’s a very impressive Chasmosaurus specimen, showing off its paper-thin, perforated frill. No way this could be for defense or for neck-balancing. That leaves thermoregulation, jaw muscle anchoring, and of course, display!

Here are some local basal ceratopsians, small, bipedal relatives of Triceratops and kin: Leptoceratops and Montanoceratops. In the same case, there was also an imported Psittacosaurus, from Mongolia.

Here’s another imported specimen, a fluffy Confuciusornis from China. I’m not really sure how and why these were imported. Maybe a collector bought them and then donated them?

The museum had enough skulls to do a comparison between the two main families of ceratopsian, the chasmosaurs (including Triceratops) which emphasized facial horns, and the centrosaurs (including Styracosaurus), which emphasized frill spikes. Mostly I think this was just another excuse to have more skulls out.

These skull bits belonged to one of the head-butting dinosaurs, the sheep-sized Stegoceras. It is pretty ridiculous how little of the skull contained brain versus how much was solid bone, and the museum has multiple specimens to prove it!

Here’s a very complete but very jumbled-up Styracosaurus, with its frill sitting on top like a present. You can also see some really good art in the background, by the same artist who did the museum’s posters and maps, showing different hypotheses on how ceratopsians walked (spoiler, it’s more like the left, upright one). This art reminds me of those Dragonology books, which had a distinct aesthetic. I should learn how to draw like that.

While I’m on the topic, this is what the promotional art looked like. There were a few monochromatic posters like this used for different purposes; if I recall correctly, some ornithomimosaurs were encouraging you to eat at the museum’s cafeteria and some therizinosaurs showed the way to the bathroom (sorry, washroom). The theropod feather anatomy had some minor issues, but generally the style and accuracy really impressed me. I would’ve bought a poster of this Edmontosaurus if it had been available and had had non-advertisey words on it.

Back to the ceratopsians, here are two of the museum’s three Pachyrhinosaurus (the one that there were numerous statues of outside, and the one depicted in the red map art above). It’s incredibly rare to get to visually compare two different individuals so directly, let alone three. The mounted specimen has some diseased toes. Cool.

Here’s the third Pachyrhinosaurus, although this one is a composite skeleton, meaning it’s made up of the bones of multiple individuals. While it makes sense to combine them to make a good display, don’t you think it’s philosophically weird to be intimately conjoined to others, possibly strangers?

Here’s another animal the museum has three of, but in this case, all three are casts, and I’m bringing it up to complain. The top skeleton is mounted well, and is located in the entry exhibit I discussed last post. The bottom skeleton is one of two that are located in the Cretaceous hall, and have numerous anatomical problems. Their coracoids (chest bones) are detached (they’re supposed to meet in the middle of the chest), their radius and ulna (forearm bones) are on the wrong sides (the bigger bone is supposed to attach to the thumb side), and their hands are pronated (facing the ground–they’re supposed to face inward like a clap). The skeleton on top has none of these issues. Maybe it was mounted more recently?

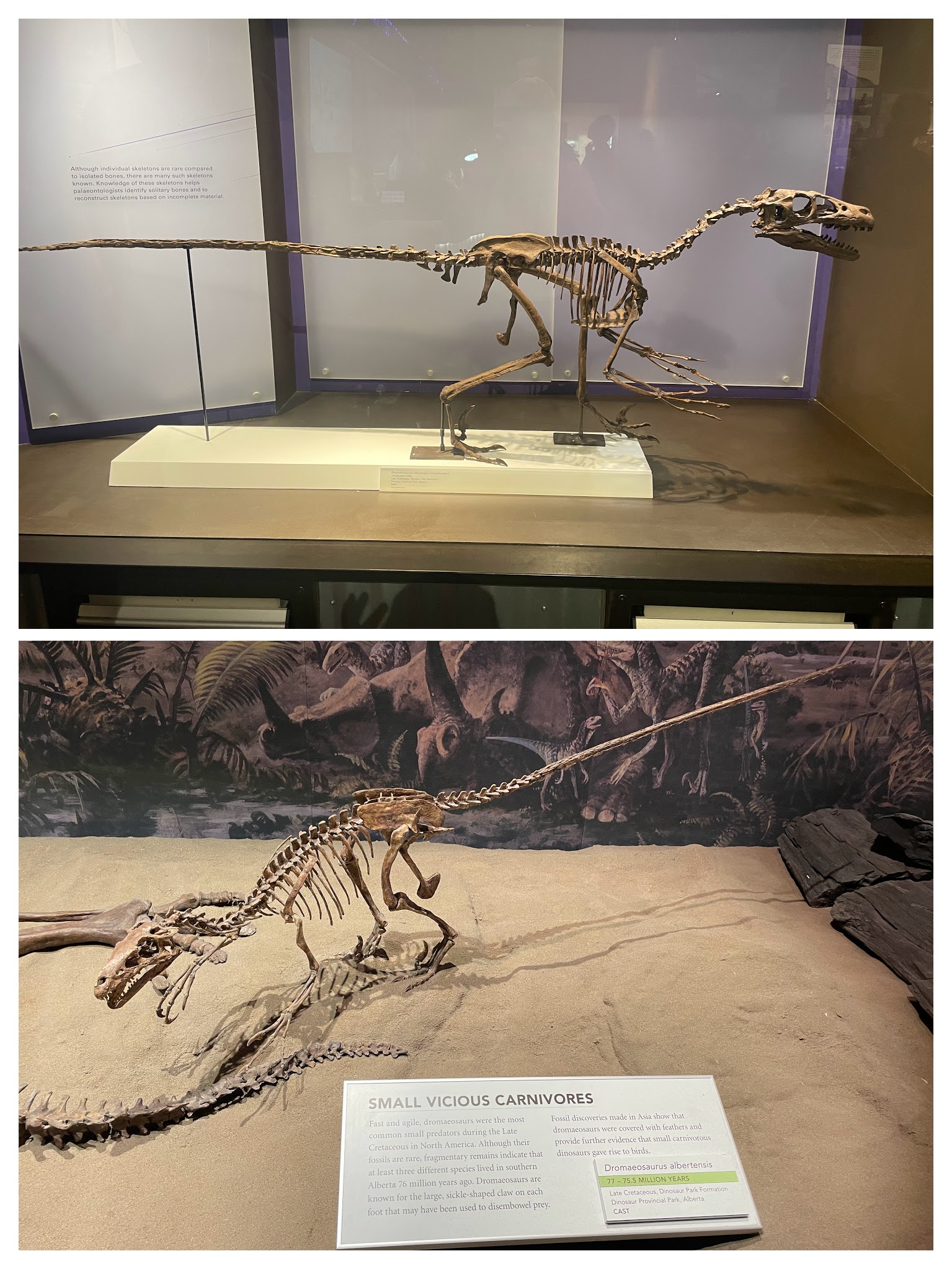

These statues weren’t in the Cretaceous hall, but in the activity center where we did the fossil casting later in the day. However, I’ll discuss them here since I’m pretty sure they’re supposed to be Dromaeosaurus. Let’s start with the positives: the feathers look more natural and birdlike than many feathered dino depictions. That out of the way, let’s criticize the negatives. The pubic bone is sticking out, the arm feathers don’t extend to the middle finger (though they also don’t go all the way up to the armpit, which is a plus), the pose is overly aggressive, and the feet are massive, as if afraid to appear too birdlike. These are common “how not to draw raptors” tropes.

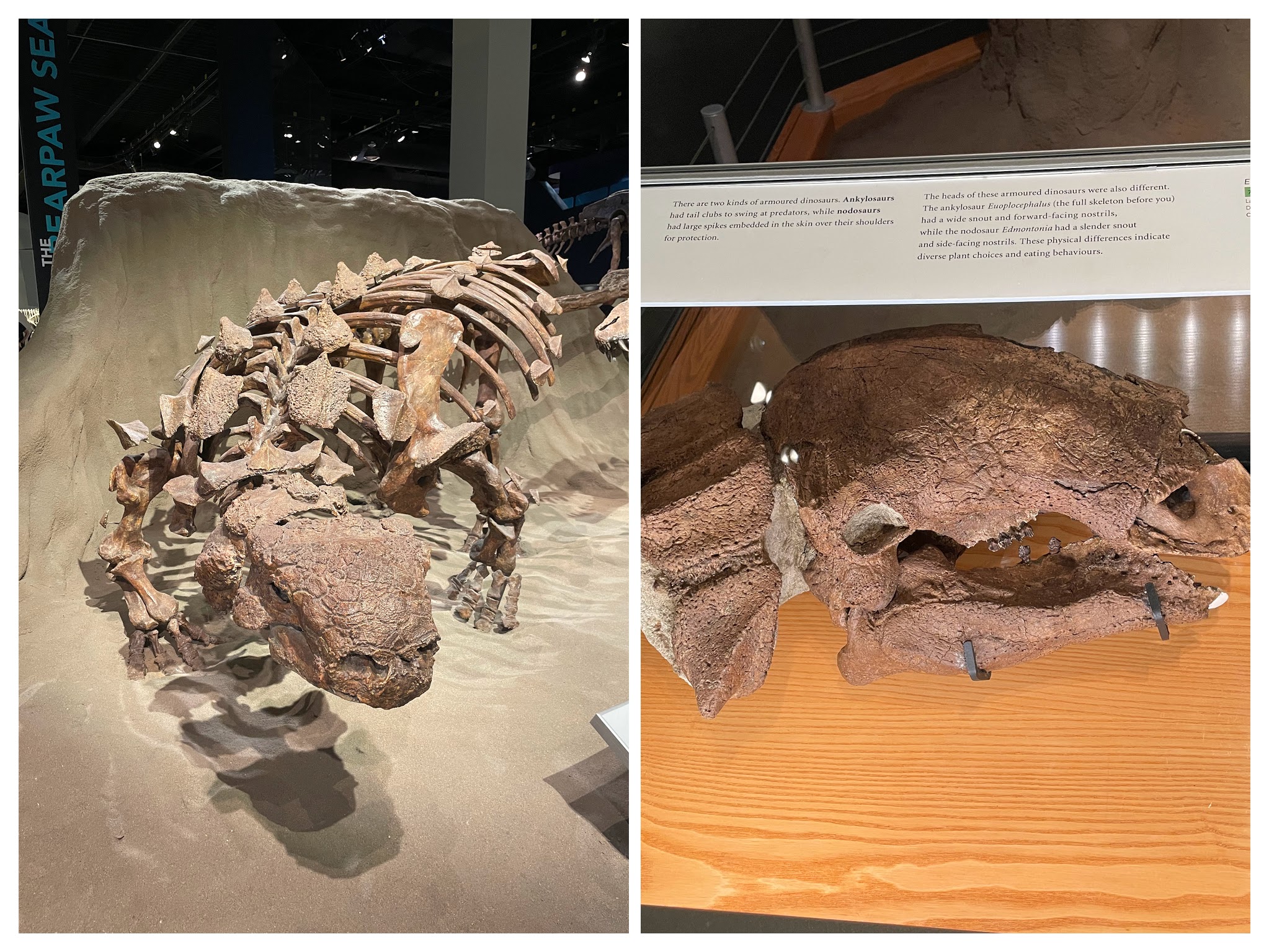

Another triplet: here’s a Gorgosaurus (smaller relative of Tyrannosaurus) terrorizing an armored dinosaur, Euoplocephalus. We saw two Gorgosaurus specimens in the entry exhibit, one articulated and one disarticulated. This mounted specimen completes the set for ways you can display a skeleton!

Here’s another angle on that same Euoplocephalus, and the skull of a different armored dinosaur, Edmontonia. The signage invites the viewer to notice the differences between the narrow nodosaur beak and the broad ankylosaur beak, showing that armored dinos weren’t just one-dimensional, but filled different niches.

This Ornithomimus is what I based the drawing at the top of this post on! Unfortunately, it shares all the same anatomical issues as the earlier Dromaeosaurus. I corrected them in my drawing–see if you can spot all the differences.

Another Lambeosaurus skull! They just keep coming!

One thing this museum did that I’ve never seen before is display disarticulated specimens in slab. I think that’s the case because most museums don’t have so many specimens that they can both give a good idea of what it looked like in life and what it looked like to unearth, so they choose to show the former. But this museum can have its cake and eat it too, since it just has so many fossils. This is Brachylophosaurus, by the way.

Here’s another hadrosaur-in-a-pile, Gryposaurus. There was also a huge mounted cast of Gryposaurus, but I’m focusing on the original material here (not something you can do in many museums!).

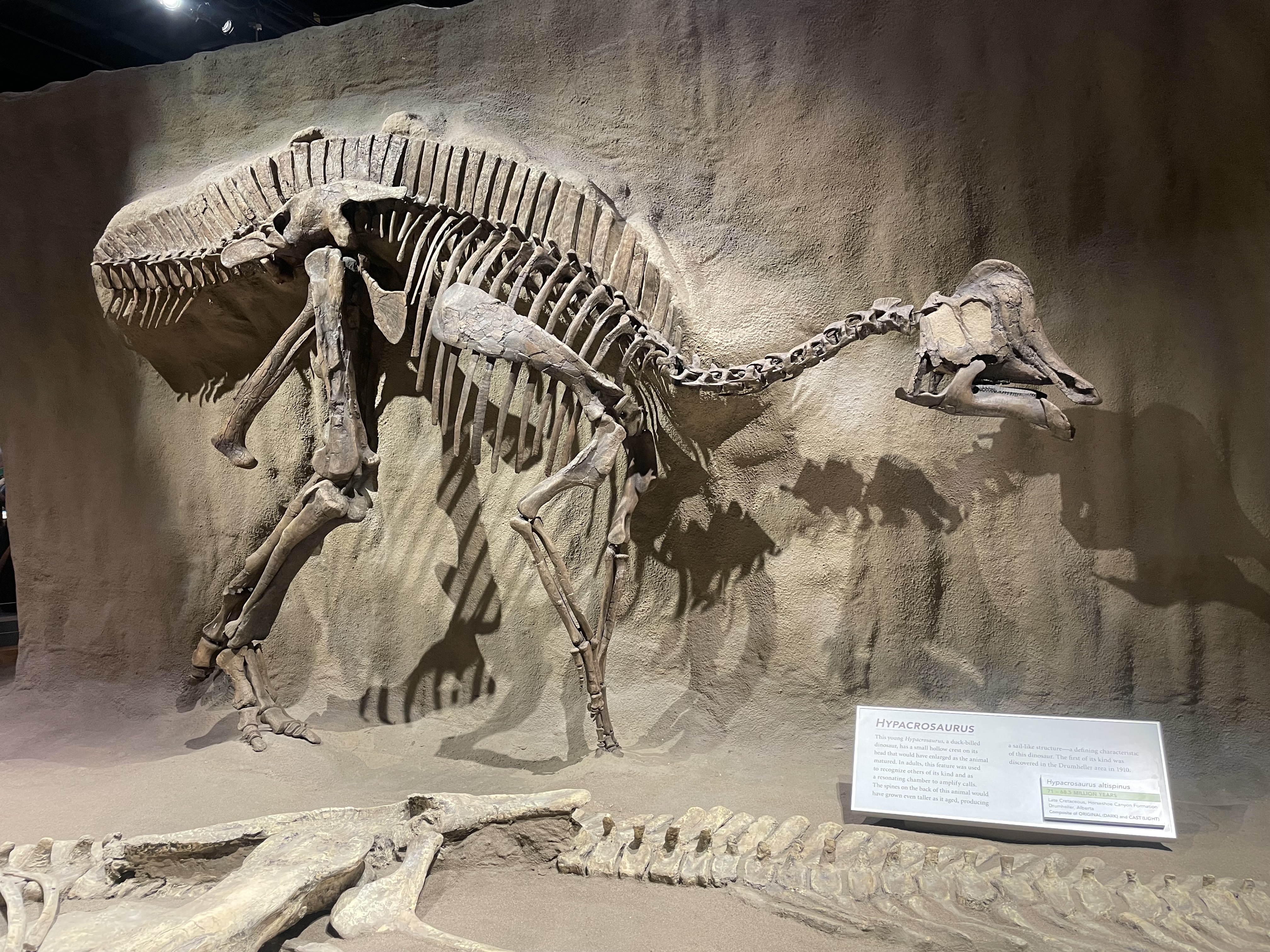

This Hypacrosaurus juvenile is the one I based my art from the last post on!

Interrupting the neverending stream of hadrosaurs for just a moment to bring you the holotype of the pterosaur Cryodrakon. I’m not completely sure, but I think this is the first real (non-cast) specimen of any pterosaur I’ve ever seen, since their remains are always so fragmentary, being very lightly built. And Cryodrakon is a hot new azhdarchid at that, only described in 2019! I love it when museums are up to the minute.

Another trackway showing how we know what we know. Since these footprints are close to the midline, we know this dinosaur walked with its legs directly under its body rather than out to the sides like a lizard. Also, snails?

Here’s another questionable mural-inspired mount, Albertosaurus (the province’s mascot) conquering a Centrosaurus. Like the funky Stegosaurus, this dinosaur’s legs are unnaturally hyperextended, but at least its arm bones and coracoids are arranged correctly. The mural also features a massive throat pouch for some reason, which thankfully doesn’t affect how you’d mount the skeleton.

No paleontology museum worth its salt lacks for a mounted Tyrannosaurus! Like the Denver museum’s anatomically impossible “dancing rex”, though, this mount has a few issues.

My main gripe is just how narrowly-set its legs are. There’s no room for a body between them! Its coracoids are also not touching, but at least its arms are pointed the right way.

Leaving the Cretaceous hall, we see the famous “fish-in-a-fish” specimen, a Xiphactinus with a Gillicus inside. Strangely, this is the second one of these I’ve seen, with a very similar but completely separate specimen located in the Denver museum. That doesn’t make this less cool though! It’s likely this Xiphactinus died because it choked on the too-large Gillicus, which must have been a thing Xiphactinus were wont to do.

Overall, the Cretaceous hall is a 9 out of 10. An overwhelming number of amazing specimens in all formats, with just a few outdated poses.

Cenozoic

As usual, I’m running out of blogging steam (and photo-taking steam) by the time we reach the Cenozoic. Just a few things left to see!

I’m a fan of this diorama of an unnamed pantodont (maybe Titanoides?)–it looks very believable and lifelike. And the explanation of adaptive radiation from the tiny Baioconodon to the medium-sized Protungulatum to the huge pantodont in the diorama, is an important evolutionary concept, and a good group to use as an example. However, the term “condylarth” is outdated, now being understood to be a wastebasket taxon.

Above the head of the pantodont, an unnamed early lemur leaps down the trunk of a tree. Given its size, it’s probably not Phenacolemur, but it makes sense they would’ve wanted something you could see clearly in the display. Imagine finding that lemur dentary–it’s so tiny, how would you even notice it?

Here are some cool Paleogene plant fossils. I don’t recall if there was signage explaining what we’re looking at, but it’s not common for a museum to give even this much screen time to plants. Now let’s get through the rest of the animals, rapid-fire:

Here’s a cool chalicothere (knuckle-walking horse relative), Moropus.

A predatory pig, Archaetherium.

A straight-tusked elephant, Gomphotherium.

A knobby-faced rhino relative, Megacerops.

A woolly mammoth being unwisely attacked by two saber-toothed cats.

And finally, a cool diorama of the bear-dog Amphicyon attacking an unnamed “oreodont”.

As usual, I’m not going to rate the Cenozoic exhibit because I didn’t give it enough attention. ¯\(ツ)/¯