This has almost nothing to do with paleontology, but glass is a fascinating material that I’ve been thinking about recently. To pay lip service to dinosaurs, here is a video of a dinosaur who loves glass:

Okay, with that out of the way let’s dive in to the physical properties of glass!

What is glass?

You may have heard as a Snapple fun “fact” that glass is not actually a solid, but a very slowly-flowing liquid. Like most Snapple “facts”, this is mostly untrue. Glass is made mostly of sand (silica) that is heated to a super-high temperature, 1723C in the case of pure silica, at which point it melts and can be cooled and molded into various shapes. It’s an amorphous solid, which means its molecules don’t have any repeating structure, a property more commonly found in liquids, hence the Snapple “fact”. However, just because glass’s microstructure is chaotic doesn’t mean it actually behaves like a liquid. A commonly cited myth is that old windows are thicker at the bottom because they have flowed slowly downward over the ages, but this isn’t actually the reason–in the past, people were often just bad at making windows! (There are certain crystalline solids, like granite and table salt, that behave like liquids under the right conditions, and are known as rheids, but glass isn’t one of them.) The amorphous nature of glass is what allows it to be blown and shaped at high temperatures: as glass is heated, it doesn’t suddenly turn into a liquid, but rather has a large temperature range in which it gets more and more gooey. At the right temperature, it can behave like rubber. Contrast this with most substances, which become a mix of completely solid chunks in a puddle of liquid as they melt, like ice, or instantly liquefy, like solder.

Glass made purely from silica is known as fused quartz, and has a very high melting temperature and low workability. Therefore, most applications of glass add other compounds to the mix to bring down the melting temperature, increase workability, and then counteract any negative effects caused by the other additives. However, optical fibers and some other specialty optical, electronics, and thermal applications use pure silica.

Why is glass brittle? This also has to do with its amorphous structure. Since the molecules are bound to each other in all directions, it’s not easy for a large group of them to slide by. In contrast, metal molecules are arranged in loosely-associated, orderly rows, allowing planes of molecules to slide past each other. As the Corning Museum of Glass Blog puts it,

A good way to think about this is looking at a simple bookcase made of wood. If all you have are the shelves and the sides, the bookcase can easily be forced to lean to one side or another since all the connections are lined up. But if you add braces at an angle, then the connections do not line up and the bookcase is much more rigid. It will not bend, but it will break under enough force. Metal has only the shelves and sides, glass has angled braces.[1]

In this post, I’m going to go over a few modern applications of glass, including fiberglass insulation, gorilla glass, and bulletproof glass and how they work.

Soda-lime vs borosilicate glass

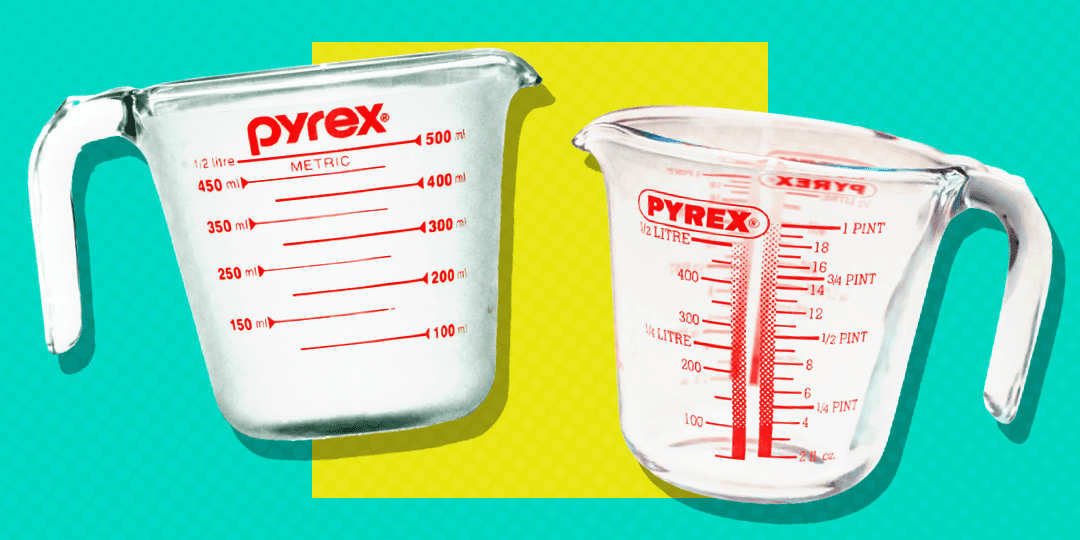

You may have heard that older Pyrex containers are more heat-proof than newer ones, which can shatter violently if microwaved or quenched. This is because older Pyrex was made of borosilicate glass, while newer Pyrex is soda-lime. You can tell the difference based on the logo: if it’s in all caps, it’s borosilicate, and if it’s lower case, it’s soda-lime. Borosilicate glass has a low coefficient of thermal expansion (three times lower than that of soda-lime), which means that it experiences less internal stress when heated than soda-lime glass, which is why it doesn’t explode in the microwave. Soda-lime glass is cheaper, but also more durable, and can withstand drops and knocks better than borosilicate.

Soda-lime glass is called that because its two main additives other than sand (silicon + oxygen) are soda ash (sodium + oxygen), which lowers the temperature at which the glass becomes workable, and lime (calcium + oxygen), which prevents the sodium from dissolving if water comes into contact with the glass. Soda-lime glass also usually contains alumina (aluminum + oxygen) and/or magnesia (magnesium + oxygen) to enhance its durability. Ninety percent of all glass made is soda-lime, including most windows, bottles, and dishware.

Borosilicate glass’s main additive is boria (boron + oxygen), hence the name, plus soda ash and alumina. In addition to the aforementioned application as heat-resistant bakeware, borosilicate is used to make chemistry containers, since it is highly corrosion resistant, and to make vacuum tubes and other devices that require a tight glass-to-metal seal. Metal alloys such as Kovar (iron, nickel, and cobalt) were invented specifically to match the coefficient of thermal expansion of borosilicate glass, allowing the glass to stay bonded tightly to the metal over a wide range of temperatures.

What’s with all these metal plus oxygen compounds? Oxygen is extremely reactive (which is why the body needs antioxidants), so it bonds to nearly everything unless we do something to prevent it. Most minerals consist of one or more metals bonded to oxygen (or sulfur, oxygen’s big brother on the periodic table). It takes work (often in the form of fire, which consumes oxygen) to get rid of the oxygen and extract the pure metals. And rusting and tarnishing is the metal subsequently reacting with oxygen in the air.

Fiberglass

Fiberglass is made in a similar process as cotton candy: glass is heated and then forced through tiny holes, creating thin, tangled strands. One common usage for fiberglass is in glass wool insulation, a soft mat material used to line building walls to keep the heat or cold out. Glass wool is a composite material, made by using a binder to glue the fibers together. It is a good insulator not because of the properties of glass or binder, but because it traps lots of little pockets of air between the fibers. Air doesn’t conduct heat very well, and the separation of the pockets limits airflow between them, further enhancing insulation. Fiberglass can also be carded and woven into cloth similarly to cotton or wool. Known as glass cloth, this material is fireproof and flexible, so it’s used in aircraft and hot air balloons. However, if you touch fiberglass, microscopic pieces of fiber break off and can poke into your skin, causing a rash (contact dermatitis), so glass cloth is not used in clothes. Workers cutting and installing fiberglass insulation are also at risk of breathing tiny airborne fibers, which can irritate the lungs, so it’s recommended that they wear protective masks while working. If the insulation isn’t disturbed though, the fibers don’t break off, so the residents of a house with fiberglass insulation aren’t at risk.

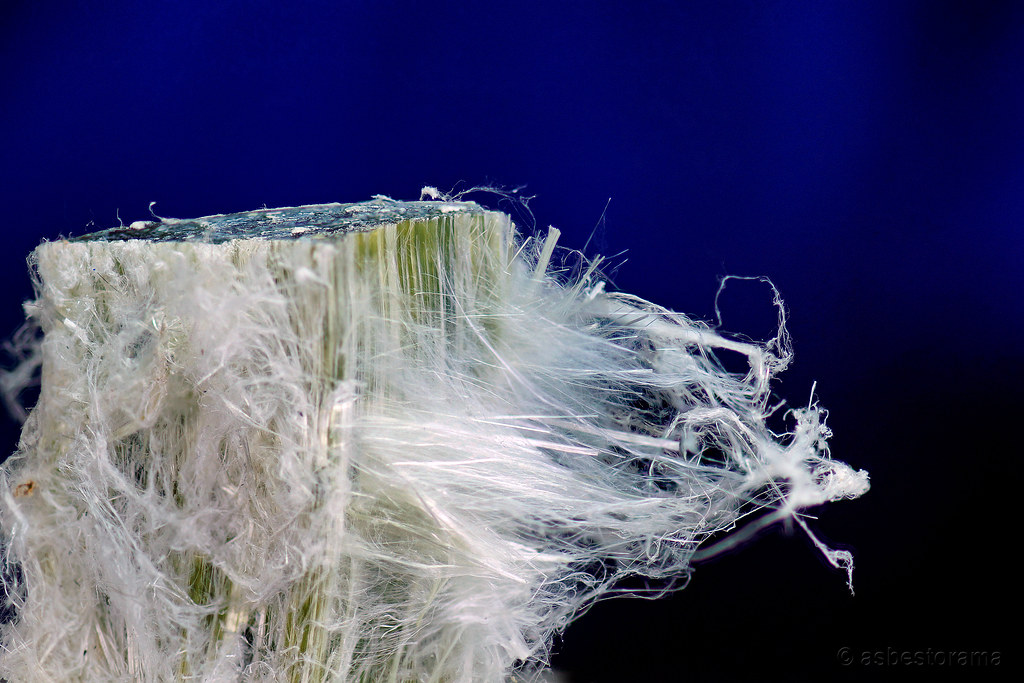

Asbestos is a very similar substance, and it works in a similar way. Unlike fiberglass, it’s a naturally occurring and abundant mineral, and can be mined almost anywhere on earth. Its fibers form because at a molecular level the mineral has structural weaknesses running all in the same direction–similar to how formations like the Devil’s Postpile are formed, but much smaller.

Asbestos is bad for you in a similar fashion to fiberglass, with the microscopic fibers breaking off when disturbed, becoming airborne, and causing lung irritation, which over years can lead to cancer. However, two factors make asbestos much more dangerous than fiberglass: its fiber size is much smaller, and it’s not biosoluble. Fiberglass fibers are intentionally created to be large enough in diameter that they don’t stay in the air for very long; they’re 3-20 microns in diameter, while asbestos fibers are close to 0.03 microns in diameter (a hundred times smaller!). And for some reason that I can’t find out, the body can eventually break down and digest fiberglass fibers, while asbestos fibers stay in place forever. (Since asbestos is naturally occurring, everyone has millions of asbestos particles in their lungs, even if you’ve never been exposed to asbestos insulation!) Thus, fiberglass doesn’t contribute to cancer risk in a significant way.

Asbestos can also be carded and woven into fireproof cloth, and people have been doing this for millennia, since the health risks didn’t used to be well understood. It was made into clothing for firemen and napkins that could be cleaned by throwing them into the fireplace, among other things that regularly were folded, rubbed, and came into contact with the user’s skin.

But how do these super-thin glass or mineral fibers not shatter when bent, carded, and woven? That brings us to…

Optical fiber

Fiber optic cables consist of a long unbroken glass filament surrounded by a plastic sheath, surrounded by additional protective coating. They are useful because they can transmit light long distances and over arbitrary, curved paths. They accomplish this through the difference in refractive index between the glass and the coating. Since light is moving through the fiber at an angle that’s close but not quite parallel with the walls, every time the light hits the glass/coating interface it bounces back in, continuing its journey along the fiber. The rhythm of light pulses along an optical fiber can be used to transmit information, kind of like Morse code, and since it’s light, it’s the fastest information transmission physically possible.

Optical fibers can be wrapped around a pencil. How do they achieve this flexibility without shattering like, well, glass? Three reasons: purity, flawlessness, and thinness. The first two reasons, purity and flawlessness, matter because of stress concentration–when something bends, if there’s an existing crack, bubble, or particle of another substance, that spot is weaker than the surrounding area and will be the first to crack further and become even weaker, leading to catastrophic failure. This is why airplane windows are oval-shaped instead of square: the corners are places of high stress concentration.

Normal glass is made by melting sand, which contains lots of impurities. Optical fibers are manufactured by combusting a silicon-containing gas called silane in a clean room environment. This means they are made of pure silica, and don’t have any other particles that could concentrate stress. Optical fibers are also manufactured in a very controlled manner: the glass is softened with heat and pulled very quickly and without touching any surfaces, minimizing the number of surface imperfections that could cause stress concentration.

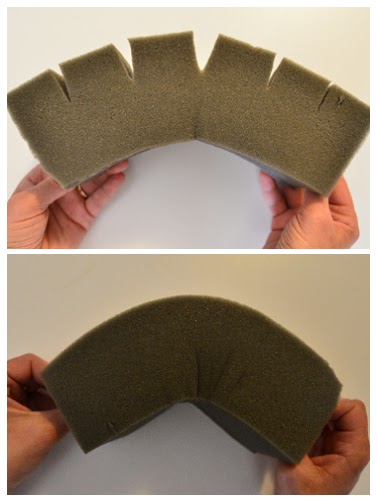

The other factor, thinness, is important in bending because the difference in length required on the convex side of a thin object versus the concave side is small. Look again at the foam blocks pictured above. To form an arch shape, the top surface has to stretch and the underside has to compress, since the length of the inner curve of the arch is smaller than that of the outer curve. If the foam were to get thinner, the difference in length between the two curves would lessen, reducing the tensile and compressive stress experienced by the two sides. Therefore, thin objects can bend more than thick ones of the same material. This is the key reason why asbestos and glass wool can be woven.

Gorilla glass

Gorilla glass is the bendy, tough, scratch-resistant glass that’s used in phone screens. It launched Corning, previously a smallish specialized glass-making company, to international importance. Gorilla glass achieves its scratch resistance through a process called ion exchange. The sodium-containing glass is immersed in a bath containing potassium ions, which act similarly to sodium ions but are larger. They replace the sodium ions in the outer layers of the glass, taking up more space and putting the outer layers into compressive pre-load. This compression makes it hard for outside objects to inflict damage, since the surface is constantly trying to hold itself together. Gorilla glass is bendy for the same reasons as optical fiber, outlined above.

Bulletproof glass

Bulletproof glass’s magic isn’t in the glass itself, but in the layering of plastic and glass together as a composite material. Composites are like material science dream teams: the weaknesses of one material are balanced by the strengths of the other. Rebar-reinforced concrete is a common example of a composite material. Rebar (long steel cables) is really strong against tension, but provides basically no resistance when compressed, instead just buckling. (Imagine pulling on a string versus pushing on it.) Concrete is really strong in compression, but useless in tension–it just cracks. When combined, they make a material that’s strong against all kinds of loads.

Note: rebar-reinforced concrete is stronger, but the difference in thermal expansion behavior between them, and the fact that rebar rusts over time, means that rebar-reinforced concrete doesn’t last centuries. Roman concrete structures are still standing more than a thousand years later because they were engineered in such a way that they didn’t require metal reinforcement.

Anyway, back to bulletproof glass. It consists of a bunch of layers of hard glass, softer glass, and plastic. The hard glass deforms the bullet, the soft glass flexes to absorb energy, and plastic holds everything together so it doesn’t break apart when damaged. The plastic also provides some resistance to non-bullet blunt attacks. One tricky part of making laminated glass like this is that the indices of refraction (optical behavior) of all the materials has to be quite close, or else visual distortions appear when looking through the glass.

The glass used in bulletproof glass is tempered, or treated in such a way that when it breaks, it will break into small, pebbly pieces rather than dangerous shards like the one that killed Doc Ock’s wife. Tempered glass is manufactured by heating glass and then rapidly cooling the outsides faster than the middle by blowing cold air on it. This causes internal stresses: the outsides are under compressive stress, while the inside is under tension. These internal stresses make it so that there are lots of built-in stress concentration areas for the glass to break at when damaged, rather than a few large cracks. If you look at a car window through polarized sunglasses, you’ll see lots of faint squares. This is a visual effect of the stress concentration. Since the molecules are pulled apart in some areas and pushed together in others, the different density areas have different optical properties.

Prince Rupert’s drop

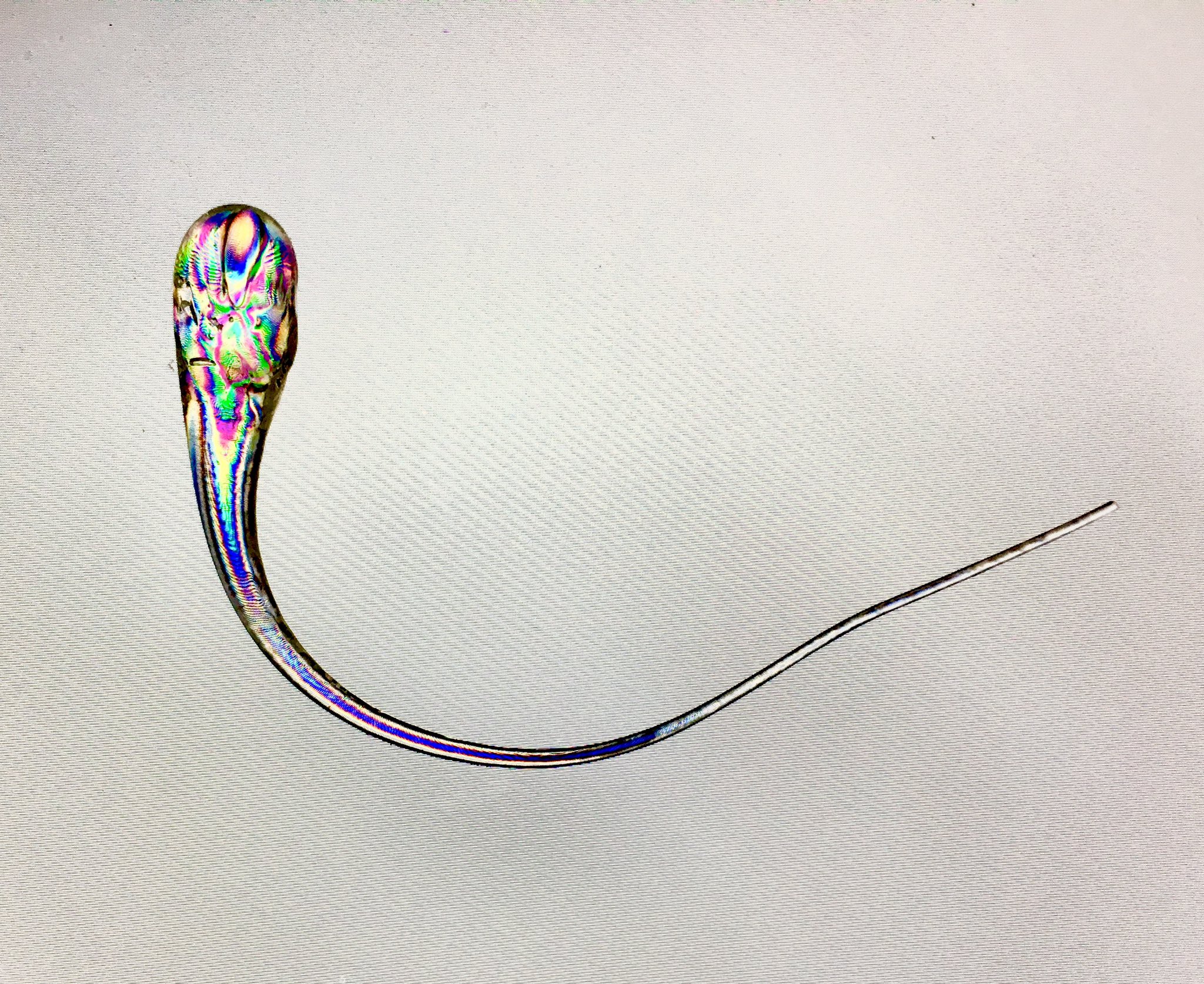

Lastly, here’s a famous case of glass tempering giving rise to some really unintuitive properties. A Prince Rupert’s drop is just a blob of molten glass dropped into cold water (quenched), resulting in a piece of glass shaped like a tadpole, with a bulbous head and a long irregular tail.

Since the cold water solidifies the outside of the glass rapidly before the inside has a chance to cool, the drop is under a huge amount of internal stress, similar to tempered glass but turned up to eleven. This means that the head end is literally bulletproof, while the tail end is ridiculously fragile. The drop can withstand gunshots to the head end without breaking, but if the tip of the tail is pinched with tweezers, the entire drop shatters, with the damage propagating from the tail all the way to the head.

Here’s a Smarter Every Day video where they shoot Prince Rupert’s drops with some big bullets. Spoiler: the drops win.

Conclusion

Thanks for bearing with me through this totally non-dinosaur-related post. Glass is such an interesting material, and we’re discovering additional useful forms of it all the time. In addition to new forms of gorilla glass, which were required to create foldable phone displays, the newest thing is willow glass, which is even bendier than gorilla glass, and is intended for the next generation of smartphones and smart watches. Funny that a substance so simple and ancient is still at the cutting edge of technology!

The page image up top is an Aarakocra character I came up with for a homebrew D&D campaign. Usually, people depict Aarakocra, a bird/human D&D race, as humans with angel wings and bird heads. But I think a bird with human arms is much funnier. Perhaps this one is going to go polish some glass.

References

[1] Kuhn, J. (2015, May 28). Part 1: Why Is Optical Fiber Flexible? Corning Museum of Glass. Retrieved March 4, 2023, from https://blog.cmog.org/2015/05/28/part-1-why-is-optical-fiber-flexible/

[2] Kuhn, J. (2015, June 3). Part 2: Why Does Glass Break? Corning Museum of Glass. Retrieved March 4, 2023, from https://blog.cmog.org/2015/06/03/part-2-why-does-glass-break/

Image credits

Pyrex vs PYREX Installing insulation Asbestos Devil’s Postpile Optical fiber Prince Rupert’s Drop