Family tree: Ornithischia > Neornithischia

Hometown: Russia, 168.3-166.1 million years ago (Middle Jurassic)

Discovered and described 2014

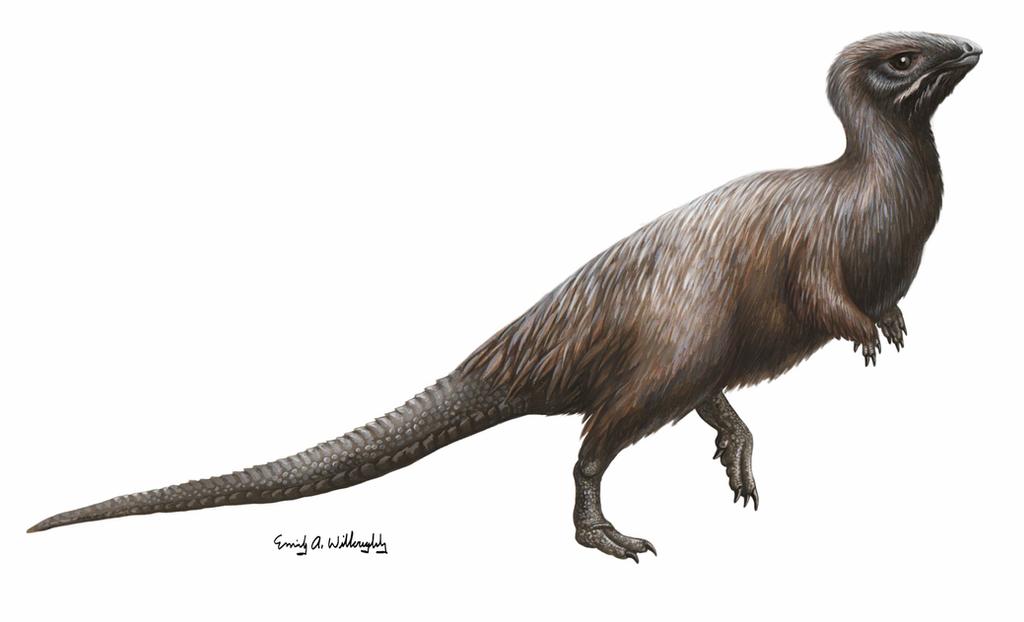

Kulindadromeus was a cat-sized bipedal ornithischian dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Siberia whose discovery completely upended the way we thought about feathers. It’s known from a bonebed containing hundreds of disarticulated specimens, many of which preserve minute details of both different types of scales and different types of feathers, accounting for data on essentially a complete life appearance of this animal. (However, no melanosome analysis has been done on Kulindadromeus, so the color is still unknown. I’m not sure if this is because the way the fossils were preserved is unsuitable for melanosome analysis, or if scientists just haven’t gotten around to it yet.)

Prior to Kulindadromeus’s discovery, a few examples of bristly or filamentous structures were known from outside Theropoda (the bird family): all pterosaurs (flying reptiles) were known to sport a simple fur-like covering, the small basal ceratopsian (horned face dinosaur) Psittacosaurus had porcupine-like quills on its tail, and similar hollow quills were known to cover much of the body of the heterodontosaurid Tianyulong. However, it was under debate whether these various types of protofeathery coverings evolved separately from the feathers of birds and independently in these groups, or if the last common ancestor of all known protofeathery animals was protofeathery–in other words, whether protofeathers were an ancestral or derived trait, and whether examples among various groups were homologous or analogous.

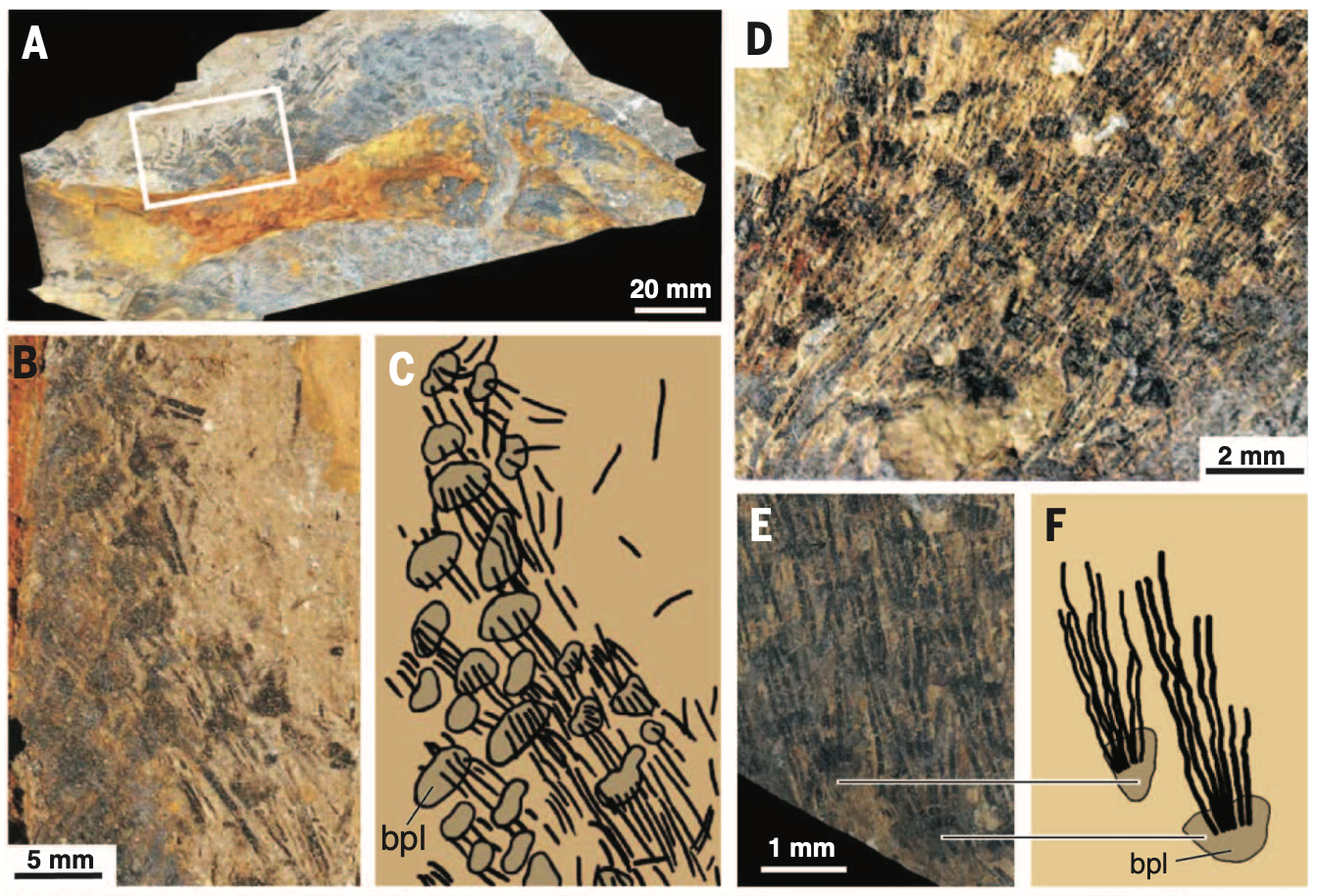

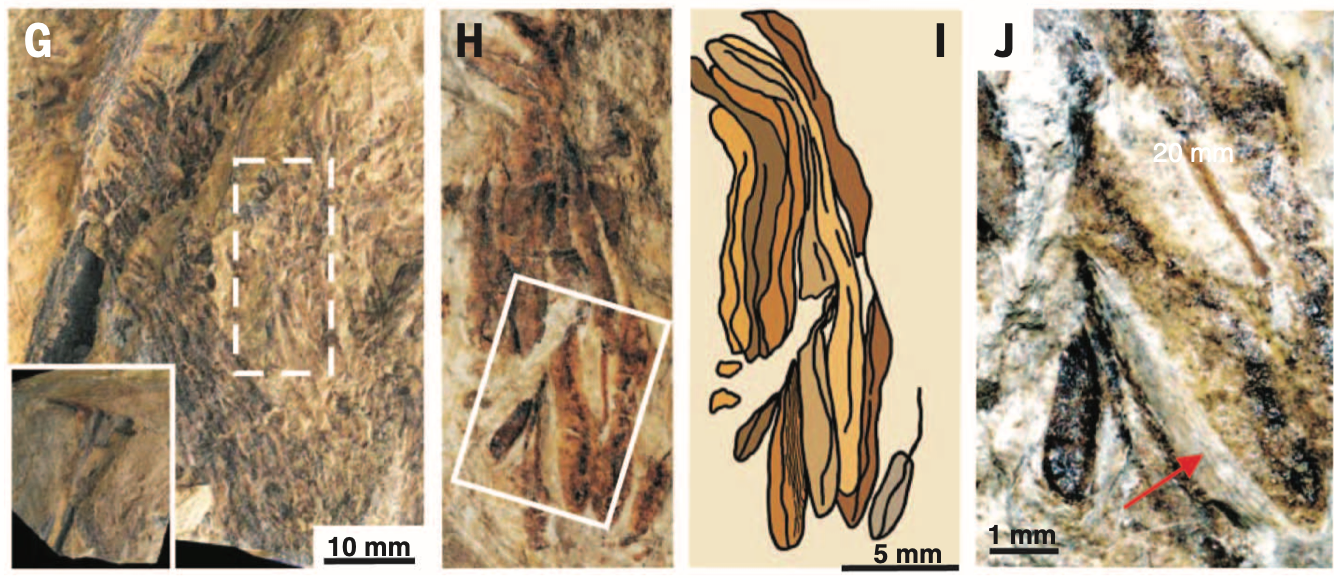

Kulindadromeus had three distinct types of filaments on its body. The simplest type, which covered most of the head, neck, and body, were thin, unbranched filaments similar to “Stage 1” theropod feathers:

However, Kulindadromeus’s other filament types looked nothing like any previously known structure. The second type consisted of a small plate or scale with six or seven downy filaments coming out of its center. The plates were arranged hexagonally (like beer pong cups), but, strangely, there was a lot of space in between each one. These were present on the upper arm and leg of the animal.

The last type of filament was a ribbon made up of very long, thin filaments running along its length. These are found only on the lower leg–the reddish, shaggy portion of the leg as depicted above. Similar ribbonlike features have been described on the tail of the scansoriopterygid (bat-winged dinosaur) Epidexipteryx, but this dinosaur is so far from Kulindadromeus on the dinosaur family tree that this trait is definitely convergent (evolved independently).

Kulindadromeus is important to the scientific community’s understanding of dinosaur integument for two reasons. First, the fact that complex protofeathery structures are present on a dinosaur outside Theropoda lends support to the idea that ornithodirans (pterosaurs and dinosaurs, including birds) were ancestrally fluffy. This conclusion is bolstered by the more recent finding that the early archosaur Azendohsaurus was warm-blooded, as well as the extremely recent discovery of Kongonaphon, a very early, very tiny ornithodiran. Since the ornithodiran line appears to have gone through a bottleneck event in which they became super tiny, and since they’re known to have been ancestrally warm-blooded, it makes sense that these small-bodied animals would have required some kind of fluffy coat to keep warm. That means that pterosaurs’ pycnofibres, Psittacosaurus’s and Tianyulong’s quills, birds’ and other theropods’ feathers and protofeathers, and Kulindadromeus’s strange plates and ribbons are probably all homologous forms based on a trait of the common ancestor to all these groups. It also means that any creature within Ornithodira is fair game, phylogenetically, for being depicted with fluff (with a fair number of caveats)!

Second, Kulindadromeus’s creative variety of integumentary structures indicates that the linear Stage 1 through 5 description of feather evolution created by Richard Prum in 1999, while useful in its time, is now out of date, and even potentially misleading. If Kulindadromeus had novel feathery structures not included on the scale, it stands to reason that there could be many more exotic structures found among other ornithodirans yet to be discovered. Viewed in a modern light, the linear scale also smacks of the ancient theory that “Ontogeny Recapitulates Phylogeny”–that, since individual birds grow their feathers in a reflection of this process through their lives, a similar process must be how the group evolved those structures. This theory has long since been discredited as predictive, though it does remain intriguing and sometimes useful. (For example, fish gonads live high up in their bodies near their heart. Human embryos begin with their gonads up by the heart, and throughout gestation, they slowly descend through the body until they reach their destination, mimicking the evolutionary process of fishlike ancestor to human.) Perhaps we don’t yet have enough data on other paths animals have taken to develop feathery structures to allow us to rewrite this scale, but we can at least conclude that dinosaur integument is more complex, diverse, and interesting than we’ve previously given it credit for.

Image credits: Kulindadromeus 1 Kulindadromeus 2 Kulindadromeus Description Paper Simplified Stage 1-5 Feather Diagram