I recently had someone ask me this question, and when I was writing my response to them, it became long enough to merit its own blog post. It’s a great question! Since most people who consume paleoart are not familiar with the fossils and the scientific analysis done on them, paleoartists represent a layer of remove between the viewer and the science. A good paleoartist makes scientific findings much more digestible–it’s much easier to get a sense of what a dinosaur looked like by looking at a picture than by reading the list of autapomorphies from a paper (“well-developed and deep prezygapophyseal spinodiapophyseal fossae…”). When not much material is known from a specific genus, it’s the paleoartist’s job to extrapolate from what we know about related animals and animals that filled a similar niche in order to fill in the rest.

While a good paleoartist bridges the gap between viewer and science, a bad paleoartist–one who claims to be basing their art on scientific fact but is really just following bad paleoart “memes”–obfuscates the science and perpetuates misconceptions, not just about specific animals but also about how prehistoric animals would’ve lived and behaved in general. Bad paleoart tends to “monsterify” its subjects, portraying them as unnaturally vicious, bloodthirsty killers, while no carnivore alive today would take massive personal risks in order to score a kill.

The accuracy of a given piece of art depends on these main factors: how much fossil material is available for the creature or creatures involved and how much these fossils have been studied and analyzed, how educated the paleoartist is and how much they care about accuracy, and how adventurous a paleoartist is in depicting unlikely but scientifically plausible (speculative) structures or poses versus playing it safe.

How well science understands the creature

There are a ton of really cool modern techniques that can deduce lots of information about an animal’s lifestyle and life appearance from its fossils, above and beyond just knowing the shape of its skeleton. For example, bone histology is the practice of cutting a very thin cross-section of a bone and looking at its growth rings under a microscope. From that, you can tell if an animal was warm- or cold-blooded, how old it was, whether it grew seasonally or year-round or even if it hibernated, if it was male or female, and if female, where its menstrual cycle was when it died. There’s probably even more that can be gleaned through this approach that I haven’t heard of. There’s also osteological correlates, which means looking at the surface texture of a fossil to deduce what sort of tissue was attached there in life. Rough (rugose) texture of a certain type indicates the skin was attached directly to the bone with little muscle or fat in between, as in a crocodile’s face; smooth texture indicates lots of soft tissue between bone and skin. Certain other types of rough textures indicate attachment points for keratin horns or antlers, and muscle attachment also leaves distinctive scars. Another scientific technique useful to paleoartists is melanosome analysis, which I’ve written a whole blog post about; it’s the main way we can tell what color dinosaurs were. It requires exceptionally-preserved fossils, so we only have patches of color on a handful of dinosaurs so far, but the limiting factor isn’t lack of fossil material, but lack of scientist time and money to do the studies. Various biomechanics methods, in which computer models of a skeleton are analyzed for mechanical stresses, are used to figure out how fast a creature was capable of moving, how much flexibility its joints had, and what likely postures it would adopt while sitting, standing, etc.

How educated the paleoartist is

There’s definitely a whole lot of underinformed, unscientific paleoart out there. The examples I see the most often are the Jurassic World franchise, children’s movies and books, and silly things like greeting cards and animated gifs. Since in art you’re forced to make assumptions–unlike in writing, you can’t just avoid mentioning something that’s in the frame of the picture–and since a ton of research and background knowledge is required to make good assumptions, it’s unrealistic to expect most artists, whose specialization is in greeting cards and not paleoart, to do the required research, or to even care. For Jurassic World, it’s a different problem–Jurassic Park was pretty accurate in terms of what was known at the time, but lots has been learned since then, and Jurassic World failed to make any updates. (I’ve heard it put this way: Jurassic Park movies were for people who liked dinosaurs, while Jurassic World is for people who liked Jurassic Park.)

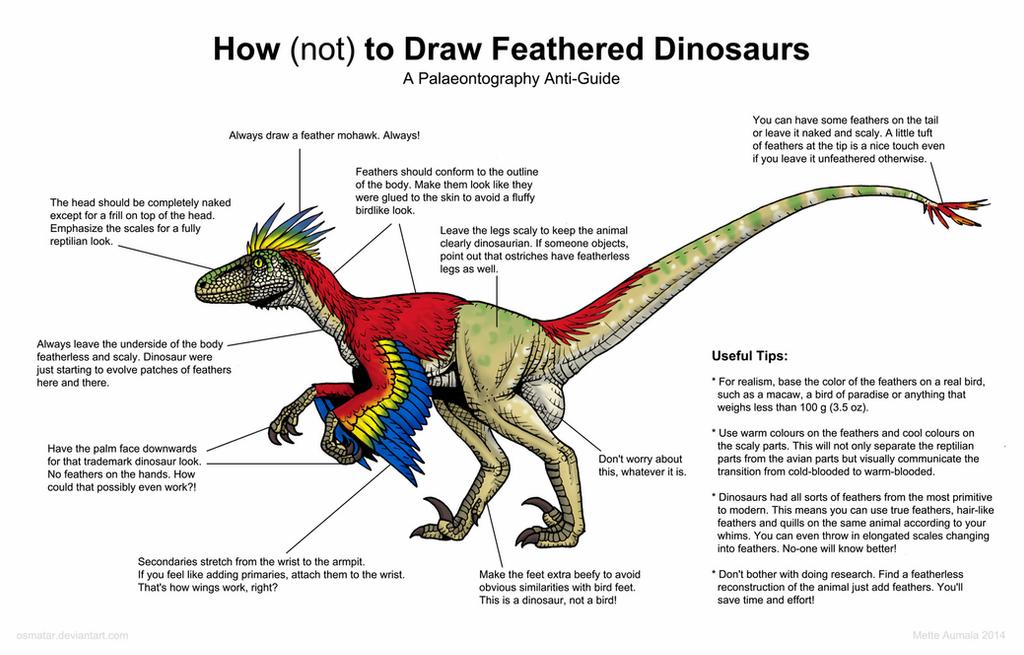

To me, those low-seriousness applications aren’t a big problem though, since no one really expects scientific rigor from a birthday card. It’s a worse problem when someone who is trying to do actual scientific paleoart, instead of reading scientific papers and looking at fossils and drawing conclusions themselves, just looks at existing paleoart and copies another artist’s assumptions and research. This is super common, especially in coffeetable books that are supposed to be scientific, because it’s much easier to do “research” that way, but it leads to the creation of paleoart “memes”–assumptions that are super widespread but may have no basis in fact. Here’s a very sarcastic infographic highlighting a lot of memes that are common when drawing “raptor” dinosaurs:

And just so you know that this nonsensical stuff actually happens, here’s an example of an artwork that was included in two supposedly scientific books for children, “Jurassic Giants: T. rex and Other Prehistoric Predators” and “Tyrannosaurus Rex and Other Ferocious Predators from the Mesozoic Era”.

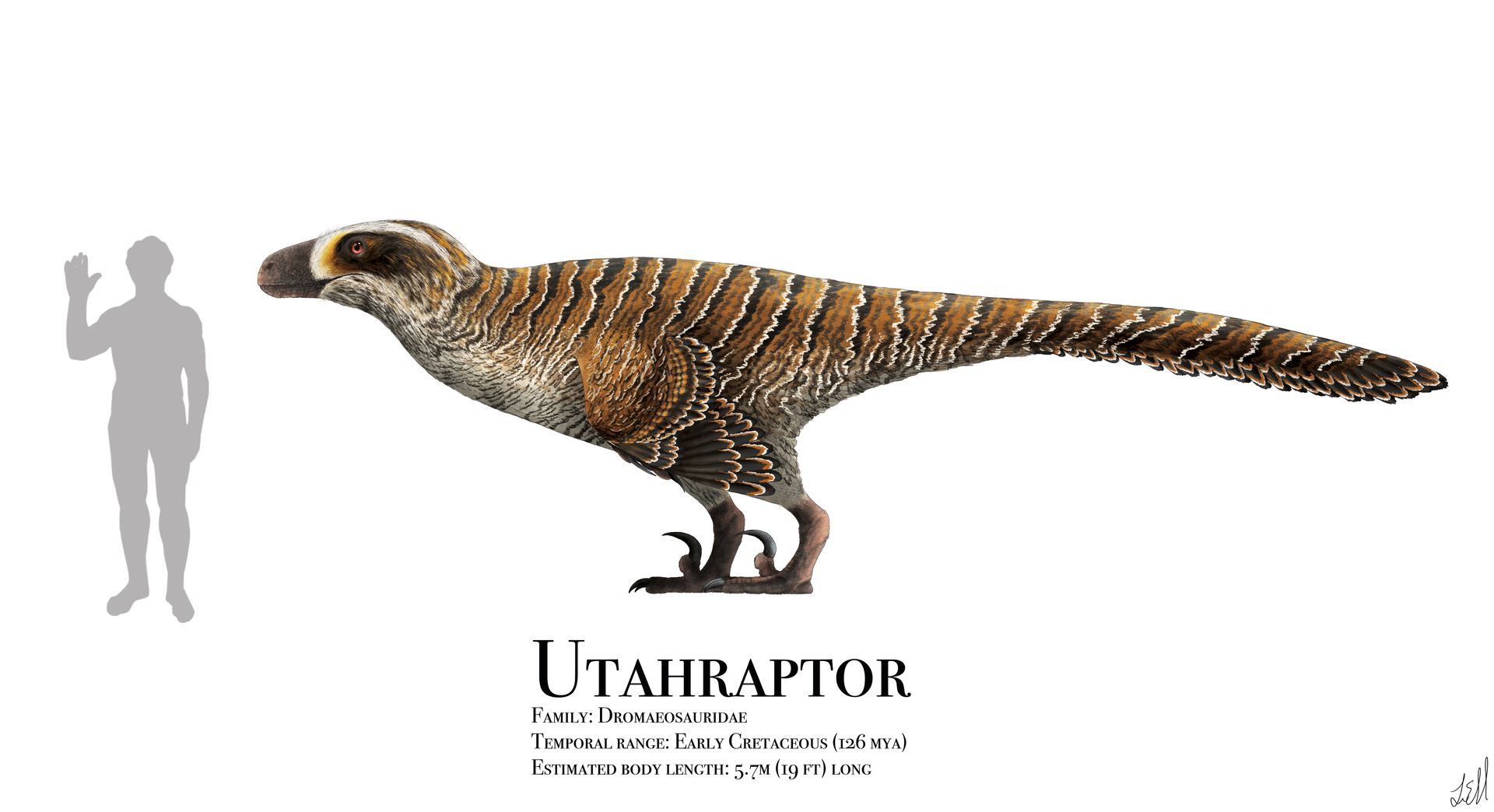

And here’s how scientists think these dinosaurs (Utahraptor) would’ve actually looked:

It looks way less monstrous and more like a real animal.

Okay, but that doesn’t answer the original question of which parts of a piece of art are speculative and which are known for a fact. For a well-known genus like Utahraptor that’s within a well-known family like Dromaeosauridae, almost all of the above picture is factual except the color, which is completely made up. As an artist you could also take liberties with the shape of the nostril, how far down the snout and how far down the legs the downy feathers go, and the overall thickness of the feather covering, but for a lot of dinosaurs even the number and placement of the big wing and tail feathers is known in detail.

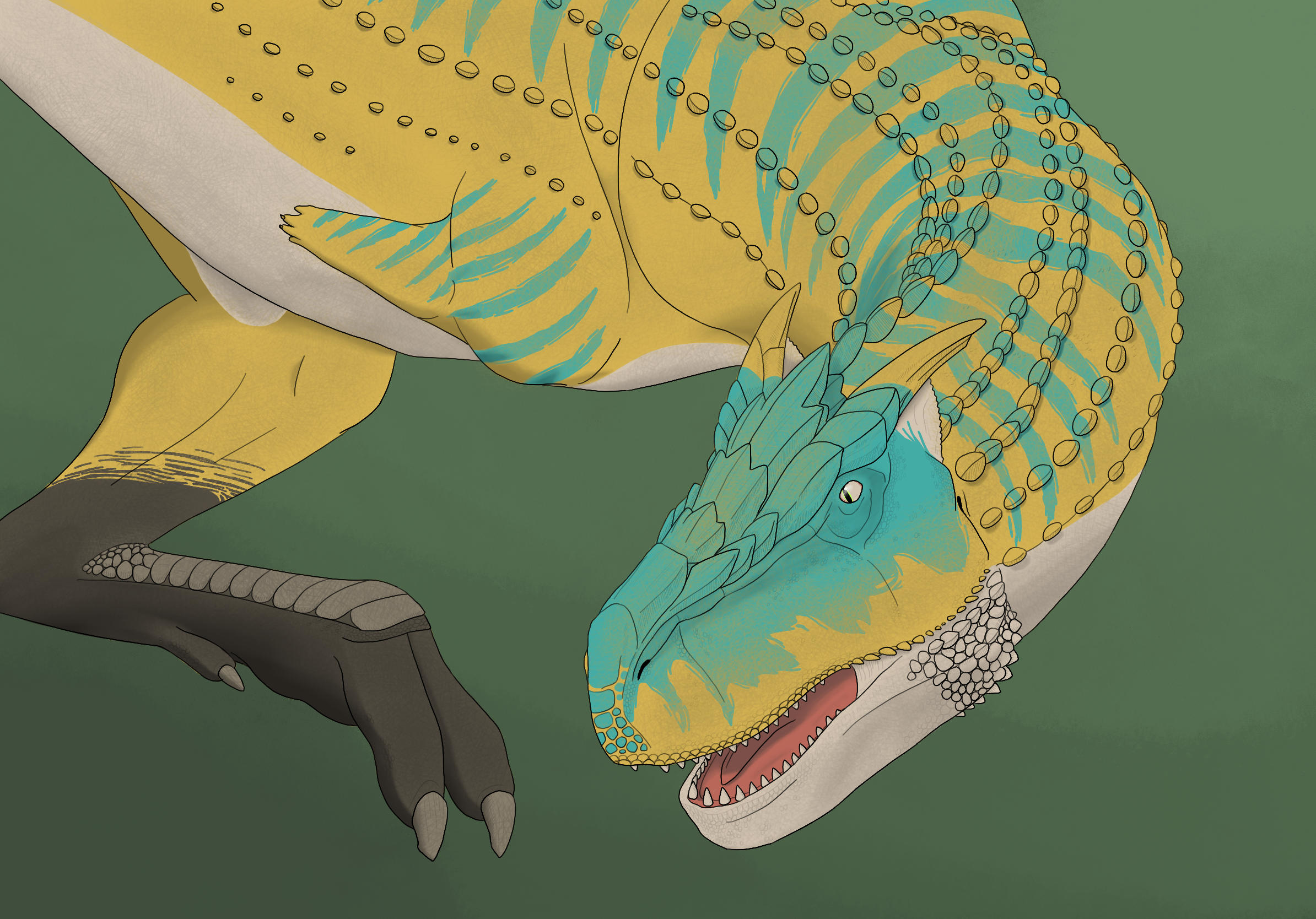

For a lot of less well-known taxa, there’s a lot of speculation that goes on. Here’s an example of a less completely known but still relatively well-understood genus, Aucasaurus:

The top picture is my interpretation, while the bottom picture belongs to Mark Witton, a famous professional paleoartist and paleontologist. (Given that, his is almost certainly much more accurate than mine!) The idea behind Mark Witton’s piece is that since abelisaurs (the family of short-faced carnivorous dinos including Carnotaurus) were fast sprinters but would’ve been not so good at turning, this Aucasaurus attempted a maneuver that turned out to be beyond his abilities, and has eaten it.

Though our knowledge of its skeleton is nearly complete, there’s still a lot of room for soft-tissue and integument speculation for two reasons: since this dinosaur was a much more distant relative of modern dinosaurs we can’t make assumptions about its skin/scales/feathers based on birds with much accuracy, and since it’s not fluffy there’s just a lot more body structure visible. The main differences in assumptions Mark Witton and I made are (1) his Aucasaurus has very minimal keratinous structures on its head, while mine has extensive horns and crests; (2) his has protofeathers on its arms while mine doesn’t; (3) his has a lot of droopy skin around its neck, including a wattle-like mantle, where mine has tight skin. Oh, and of course the color, which in both cases is totally made up, but my choice of neon colors is admittedly unlikely. But for all the rest of the differences I listed above, both interpretations are scientifically plausible.

How adventurous or conservative the artist wants to be

This is the most exciting part of paleoart! I’m not a scientist, but when I look at the data and conclude that croc-relatives with big ears are a real possibility, and then I make art that reflects this and show others, I’m helping to spread knowledge about these animals, inviting criticism and alternative interpretations and thus learning more myself, and contributing a tiny bit to the body of scientific knowledge. I had to do loads of research to get to the point where I was able to do this, but it was definitely worth it.

Here’s one final example, contrasting a highly speculative depiction with a conservative one.

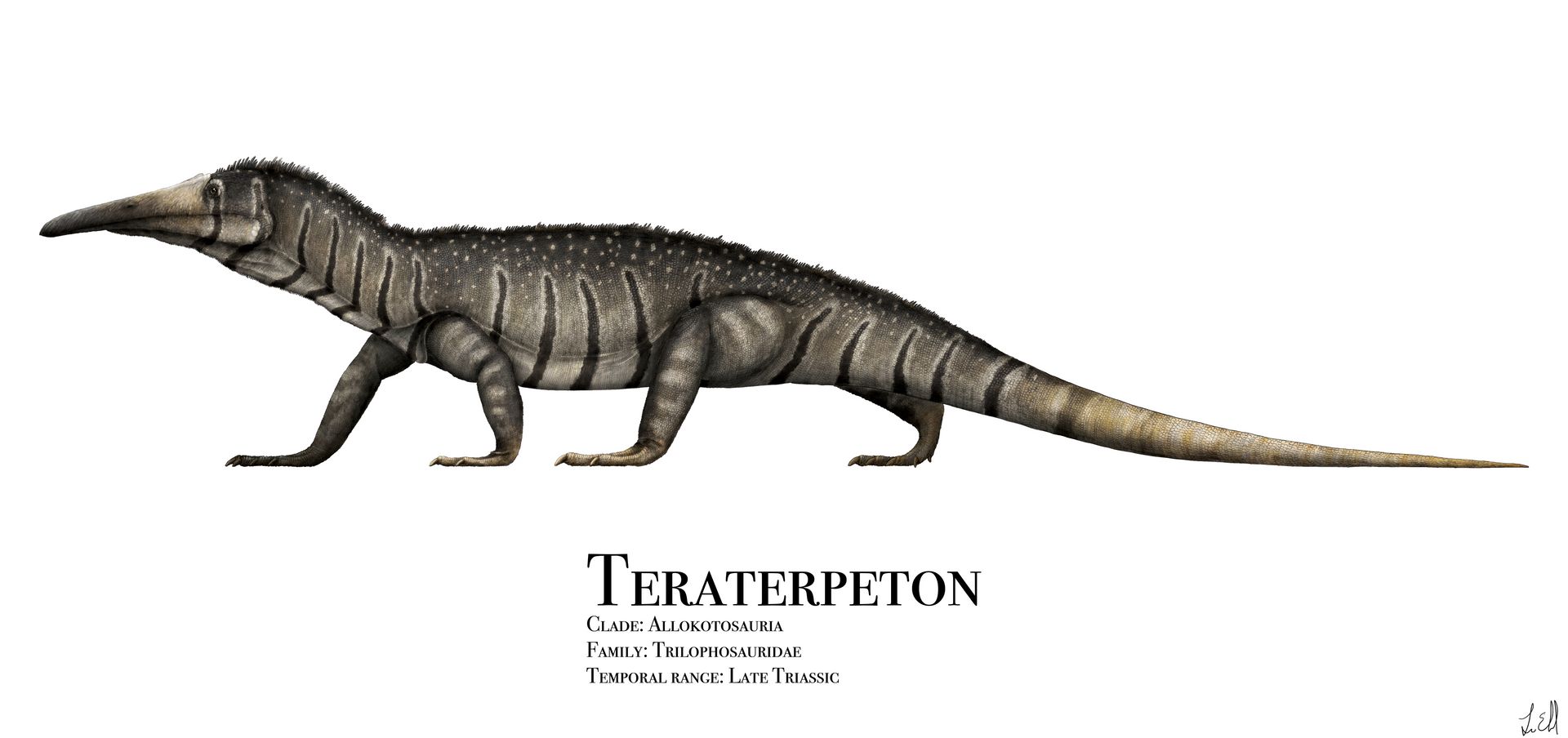

This is Teraterpeton. From this picture, it looks very birdlike. What would you expect the rest of the body to look like?

Probably not like this! Yes, this is the same animal, the allokotosaurian archosauromorph (early relative of crocs and birds) Teraterpeton, from Late Triassic Canada. Traditionally, early archosauromorphs have been depicted as outwardly more similar to lizards than to birds, which sort of makes sense given their lizard-like body plan, but since they’re actually more closely related to birds than lizards, and since a recent study found that they were actually ancestrally warm-blooded, can we really call the birdlike interpretation “speculative” anymore? (For a more in-depth look at this particular question, see my other post on which archosaurs should be fluffy.)

Paleoartists have a responsibility, being the bridge between the public and science, to make sure our art is not lazy and does not rely on memes or outdated assumptions, and to do our best to portray ancient animals with as much vibrance and complexity as modern ones. Viewers implicitly trust what they see, especially when it’s presented in a book that’s supposed to be grounded in fact, since the assumptions behind a particular piece of art are invisible. By creating paleoart that is diverse, speculative, and creative, but always rooted in science, we can remain deserving of that trust, and we can use it to break down misconceptions, spread new scientific knowledge, and inspire future paleoartists to get drawing!

Further reading

If you’re interested in learning more about best practices for paleoart, I’d highly recommend checking out All Yesterdays, a little book by three very famous, well-credentialed paleoartists that kicked off a revolution in paleoart in its encouragement of adventurous, speculative, but scientifically plausible depictions of animals that break paleoart memes and norms. It also includes depictions of modern animals in the style of bad paleoart, including venomous baboons, trunkless elephants, sail-backed rhinos, furry iguanas, and more. Another good resource for paleoartists is The Paleoartist’s Handbook, by Mark Witton. It goes more in depth into artistic interpretation of scientific findings, and discusses specific groups of animals, and even specific paleoart memes to avoid.

A note about the page image: this is my drawing of the nodosaur from Early Cretaceous Canada, Borealopelta, known from a spectacularly-preserved mummy described in 2017. I chose this to be the page image because it’s probably the most scientifically factual piece I have ever attempted–since the fossil of Borealopelta is so exquisite, we know a ton about its life appearance, habits, and environment. From melanosome analysis we know that it was rusty red on top and pale underneath, we know the exact life placement of all its osteoderms (bony knobs and plates embedded in the skin) because the mummy kept them all articulated, and we even know its last meal consisted of charcoal and ferns, because the stomach contents were preserved too. This meal indicates that perhaps Borealopelta was a pioneering herbivore that was one of the first animals to resettle an area after a forest fire.

Image credits: How Not to Draw Feathered Dinosaurs Monstrous Utahraptors Utahraptor Aucasaurus Birdlike Teraterpeton Lizardlike Teraterpeton