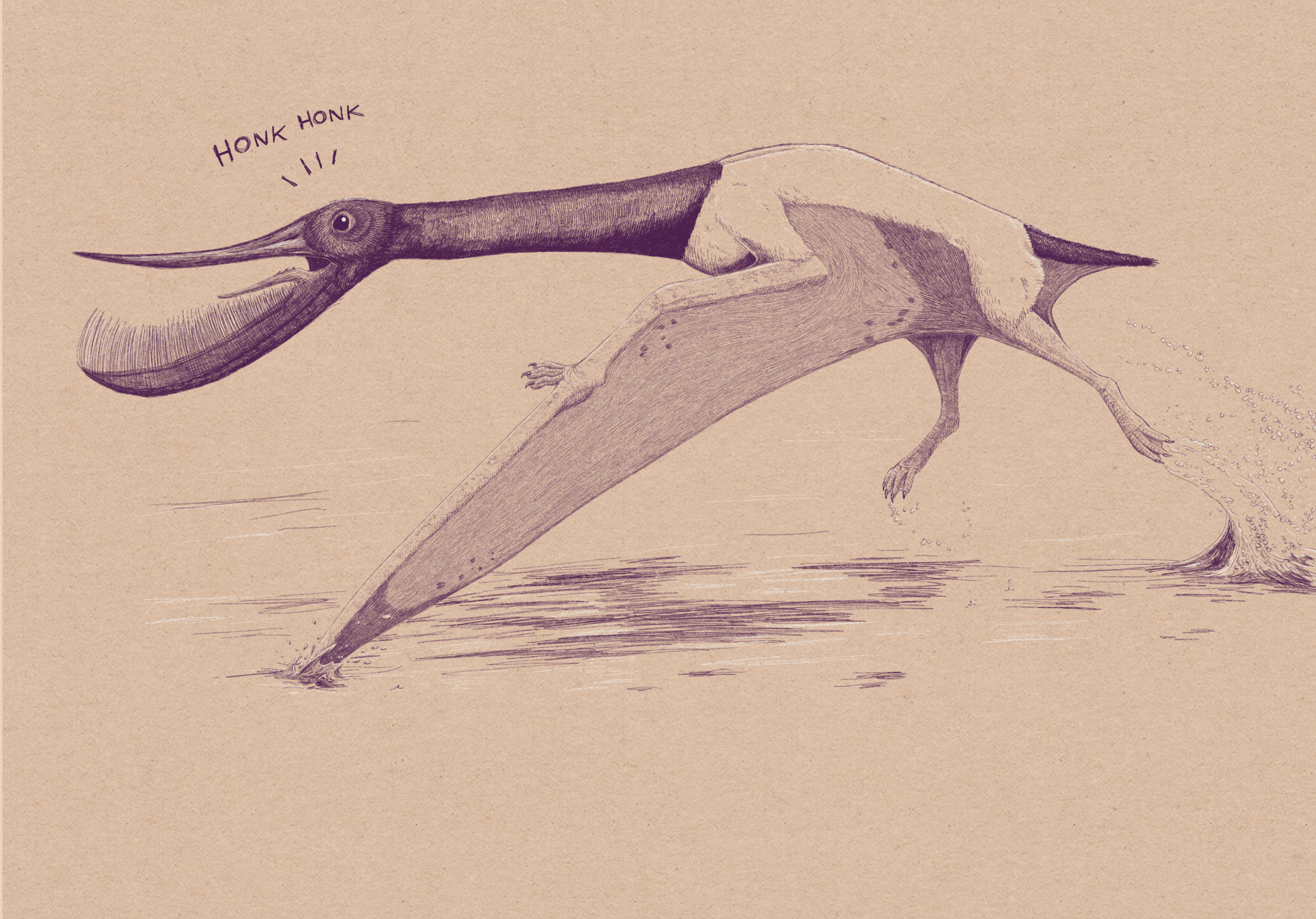

Take a moment and think of the myriad lifestyles different birds live. Some are flightless, swift-running herbivores; some are terrifying aerial hunters; some dive for fish; some nab insects on the wing; et cetera et cetera. Many of these niches can only be occupied by a largeish flying creature, so it’s no surprise that many roles we observe birds filling today were in the past filled by pterosaurs, the large membrane-winged flying reptiles of the Mesozoic Era. When depicted in fiction, pterosaurs are often relegated to play the part of aerial monster, swooping down to carry hapless bystanders away to their roosts. However, this is one behavior that pterosaurs definitely never did. (Their feet were incapable of grasping.) In this post, I’ll give just a few examples of specialized pterosaurs, starting with our flagship monster, Pterodaustro (depicted in the page image above). Hopefully you’ll be surprised by the wide range of things pterosaurs were capable of!

Pterodaustro

Family tree: Pterosauria > Pterodactyloidea > Archaeopterodactyloidea > Ctenochasmatidae

Hometown: South America, 105 million years ago (Early Cretaceous)

Discovered 1969, described 1970

The components of Pterodaustro’s name are not “ptero” and “daustro,” as I first thought, but “ptero,” “d,” and “austro,” meaning “wing of the south”. Thus, to make the etymology clear, I professionally recommend we stylize it as Pterod’austro and will refer to it as such for the rest of this post.

That aside, Pterod’austro was a goose-sized pterosaur with proportionally stocky limbs and large, probably webbed feet. Its defining feature was the forest of thousands of fine bristly teeth protruding from its lower jaw, which would have been used for straining plankton from water like baleen. It is the only pterosaur known to have such a feature, though other pterosaurs have more primitive forms of straining teeth (more on that later).

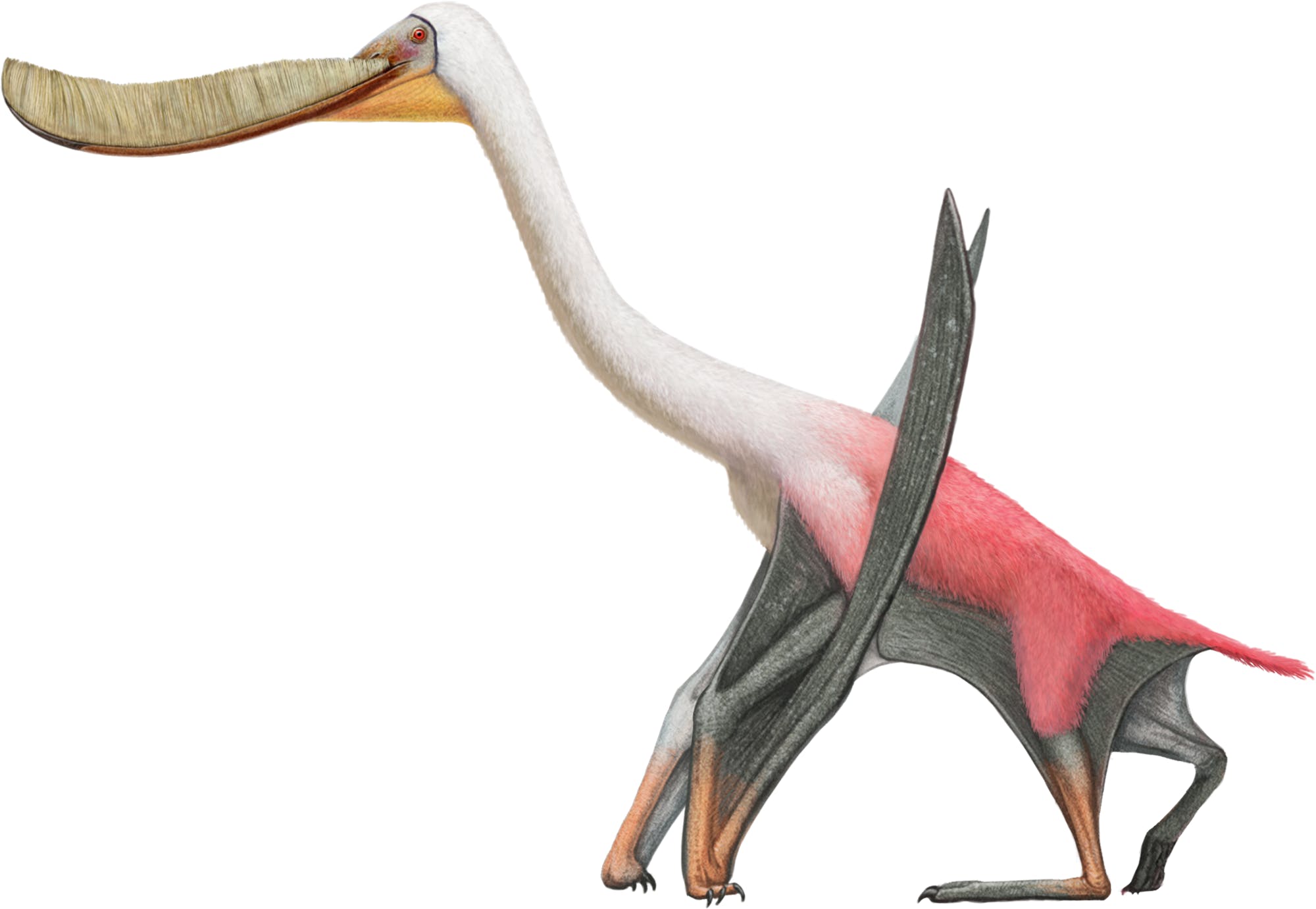

Since it would’ve subsisted on a diet of plankton and small invertebrates, it probably would’ve been pink, due to the same mechanism that creates modern flamingos’ and spoonbills’ pinkness. These creatures absorb beta-carotene that’s produced by algae, either directly by eating the algae or indirectly by eating creatures that have eaten algae, and sequester it in their feathers or pycnofibres (pterosaurs’ furlike fluffy coat). While flamingos are unique in feeding with their heads upside-down, and thus have strongly downward-curved bills, Pterod’austro’s upward-curving bill indicates that it kept its head upright while feeding, perhaps using a scoop-and-then-strain strategy.

Pterod’austro is known from hundreds of specimens representing all growth stages from embryo to adult, so we know a lot about its ontogeny (growth) and reproduction. And wow, is it different than what we think other pterosaurs did. The prevailing view, based on eggs and juvenile specimens found in China, is that most pterosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs, buried them in dirt or sand, and abandoned them, similar to sea turtles. The flaplings (yes, baby pterosaurs are called flaplings. Isn’t it great?) that emerged would have been superprecocial and able to fend for themselves shortly after birth.

However, Pterod’austro apparently didn’t do this. Its eggs had hard but thin shells, and analysis of their gas-exchange properties indicates that they would have needed to be incubated in a very moist environment while still remaining clear of mud that could choke the embryo. The micro-structure of the eggshell is similar to that of flamingo and grebe eggs, which, along with what we already know about Pterod’austro’s lifestyle and environment, means that they probably constructed nests and took care of their eggs and young. Furthermore, the nests were probably similar to a flamingo’s mud tower or a grebe’s floating raft nest, which is cool to imagine. The fact that all >750 Pterod’austro specimens are known from a single, fifty-square-meter bone bed indicates that they were colonial, also similar to modern flamingos.

Since modern animals tend to all favor hard- or soft-shelled eggs consistently within their clades, there was a bit of stir when it was proposed that Pterod’austro laid hard-shelled eggs while other closely related pterosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs. However, recent evidence that certain dinosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs while others laid hard-shelled eggs provides another example indicating that maybe the hard versus soft distinction is more flexible than previously thought. It’s also pointed out in the Pterod’austro egg study that some gekkotans (lizards related to geckos) lay soft-shelled eggs while others lay hard-shelled eggs, so our prejudice toward believing a group must choose one or the other was probably totally unfounded to begin with.

Leptostomia

Another waterbird mimicking pterosaur that made headlines recently is the tiny Leptostomia. It is known from a single specimen comprised of just the long beak, but a lot can be inferred despite the fragmentary remains. It was probably an azhdarchoid, a close relative of the largest animals to ever fly, but Leptostomia itself was only about a foot long, or less.

I like the above picture because it conveys the scale well, even though it’s less photorealistic than some other Leptostomia depictions. A lot of paleoart suffers from making its subjects look the wrong size, due to neglecting the way proportions change depending on the absolute size of the animal.

Leptostomia was a probing pterosaur, meaning it would’ve stuck its long, thin beak into the mud in order to nab invertebrates. Since mudflats today support a ridiculous diversity of different shapes and sizes of probing birds, I wouldn’t be surprised if we uncovered more probing pterosaurs in the future.

Ctenochasma and friends

Ctenochasma (meaning “comb jaw”) and its kin were closely related to Pterod’austro, but didn’t have as highly developed a feeding system. Instead of thousands of teeth, they only had a few hundred, and instead of pumping water through baleen they would have caught individual aquatic invertebrates in the “net” of their teeth like a modern spoonbill. This diet would’ve made them, again, pink, but perhaps only subtly so.

Above: Gnathosaurus, a ctenochasmatid pterosaur that sports a confusing name due to the fact that it was originally mistaken for a crocodilian.

The spoonbill’s life is a tough one: since the strategy of eating one bug at a time is so inefficient, they have to feed for hours every day. Ctenochasmatids probably had a similar lifestyle.

Another famous pterosaur that had a superficially similar tooth arrangement to the ctenochasmatids was Rhamphorhynchus, and some of its close relatives. These gull-sized pterosaurs were part of an older evolutionary lineage, and only had a reasonable 34 needle-like teeth, which were used for catching fish. They also had a fun kite-shaped vane on the ends of their long tails.

Paleo fiction and art often depicts pterosaurs as skim-feeding or plunge-diving, but they would have been incapable of either, due to the fragile structure of their skulls. Rather, Rhamphorhynchus and others would have swum like cormorants to catch fish underwater. I have a hard time picturing swimming pterosaurs, since no animals with remotely close body plans do anything like this today. Maybe the closest analogy would be a manta ray?

A recent study showed that unlike birds and bats, which usually start life with underdeveloped wings that grow proportionally more quickly than their bodies until they become flighted adults, Rhamphorhynchus young looked proportionally like mini adults (known as isometry). This indicates that even the smallest Rhamphorhynchus were capable of flight, an example supporting the superprecociality hypothesis for pterosaurs.

Giant azhdarchids

Last but not least, we have the largest animals ever to fly, the plane-sized azhdarchid pterosaurs. A new study that came out this year shows that while a majority of pterosaur groups became more efficient fliers over time, even when accounting for size, the giant azhdarchids, which were some of the last pterosaurs, were actually much less efficient fliers than evolutionarily expected. This indicates that they were more ground-based than other pterosaur groups, and would only have taken to the air to cross large distances. Maybe they were even on their way to becoming flightless, and would have if they weren’t wiped out by the asteroid impact 66 million years ago.

Above: The giraffe-sized Hatzegopteryx, one of the contenders for largest flier ever (alongside Quetzalcoatlus and Arambourgiania), was the apex predator of Hatzeg island, and would have preyed on dwarf sauropods and ornithopods (examples of insular dwarfism). Isn’t that an amazing ecosystem to imagine?

Conclusions

There’s tons of pterosaur diversity I didn’t cover in this post, such as the clam-digging dsungaripterids, the batlike anurognathids, and others, but this profile was really supposed to focus on Pterod’austro and I got a bit carried away. Pterosaurs in fiction are often relegated to stereotypical roles, and in reality they were so much more interesting and varied. It really shouldn’t be surprising every time we find new pterosaurs that filled niches we didn’t think they were capable of filling, especially early on in their evolution when there was no competition from birds. While pterosaurs often don’t fossilize well since their bones are super delicate, new advances in 3D scanning have allowed researchers to study fossils they never would’ve been able to access in the past. I anticipate tons of great new pterosaur genera will continue being discovered, and hopefully I can cover some of the exciting ones in a future post!

On a more mundane note, you may have noticed I didn’t post anything last week. I’ve decided that this year I will only be posting new content every other Wednesday. I’ve had tons more at-home time this year for obvious reasons, and anticipate having less of it in the coming year, and don’t want my quality to suffer due to weekly deadlines. So, keep an eye out in a fortnight for the next post. Thanks for reading!