I’m getting married soon, and of course we have to have something dinosaur-themed at the wedding. Instead of the tables at the reception being numbered, I thought I’d do a minimalist take on a second Alphabestiary and make the tables named after dinosaurs. Unlike the first Alphabestiary, in which I picked the dinosaurs with the weirdest names for each letter, I chose these dinosaurs as being the most edifying to a beginner–representative of many important clades, and a little obscure but not too obscure. Here’s a sneak preview!

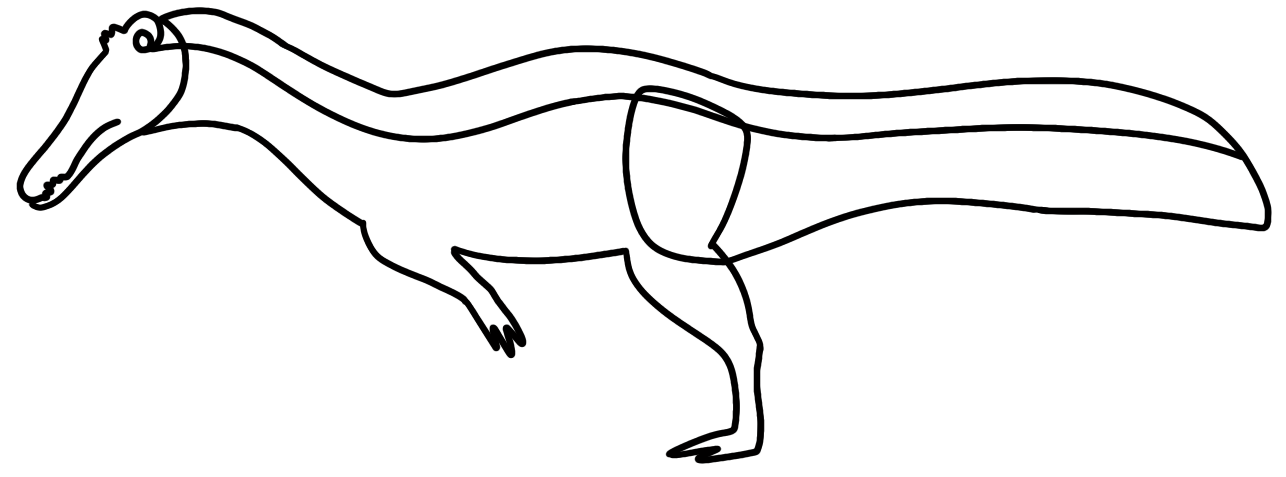

A is for Austroraptor

While, at the end of the Age of Reptiles, the Northern Hemisphere boasted famous “raptor” dinosaurs like Velociraptor (which was actually the size of a turkey) and Deinonychus (which the Jurassic Park “raptors” are actually based on), the Southern Hemisphere was home to their close relatives, the long-snouted, fish-eating Unenlagiinae. Austroraptor was one of the biggest “raptors” ever—at around 225kg (500lb) it was the size of a lion.

B is for Borealopelta

This armored herbivore is one of the few non-feathered dinosaurs we know the color of! Scientists looked at the exquisitely preserved fossil under a microscope and determined that its back would have been rusty red while its underside was pale.

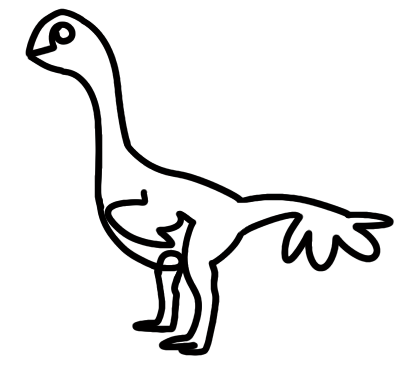

C is for Coelophysis

This dog-sized, snake-necked carnivore was one of the most ancient dinosaurs. It was an early member of the family that includes modern birds. It was a lot dumber than more advanced dinosaurs—there’s no room for brains in that long skinny skull!

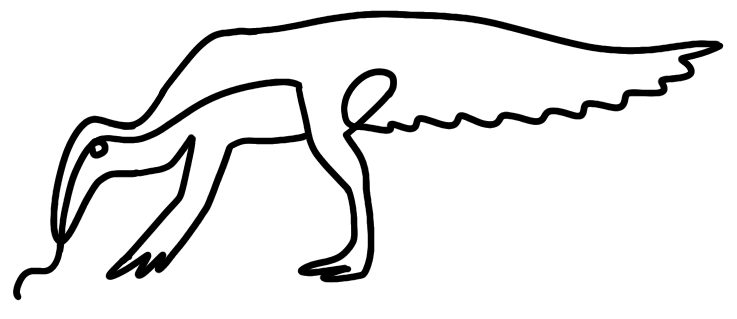

D is for Dilophosaurus

Though this dinosaur was depicted in Jurassic Park as a shoulder-height, neck-frilled venom spitter, it was actually much larger and there’s no evidence for a frill or for venom. This was the first time dinosaurs reached apex predator status, in the Early Jurassic; before that, croc relatives and mammal relatives had held the top spot.

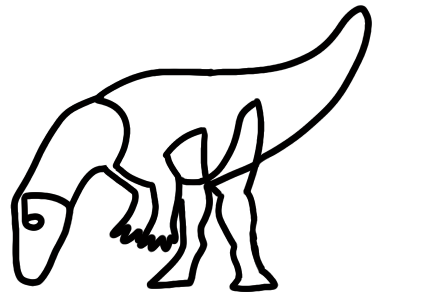

E is for Edmontosaurus

This enormous “duck-billed” dinosaur lived in the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek environment alongside Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. We have multiple “mummified” specimens that preserve soft tissue, so we know it had a rooster-like comb, hooves on its front feet, and square, castle-like scales along its back.

F is for Falcarius

Falcarius was an early member of the therizinosaur family, a group of bird-lineage dinosaurs that grew huge claws and became high-browsing herbivores, sort of like the giant panda. They had special adaptations in their hips to make room for a big fermenting gut that would allow them to subsist on roughage.

G is for Gigantspinosaurus

The largest and most famous stegosaur is Stegosaurus, but there were many others that had different shapes and configurations of plates and spikes. The cow-sized Gigantspinosaurus had modest plates, but enormous shoulder spikes in addition to the standard thagomizer (tail spikes).

H is for Halszkaraptor

While modern birds have evolved to live many types of semi-aquatic lifestyles, this was very rare for non-bird dinosaurs. One of those that did was Halszkaraptor, a small, cormorant-like fish-eating “raptor” dinosaur. We know this because it had dense bones, fish-catching teeth, and proportions similar to modern swimming birds.

I is for Ixalerpeton

This isn’t technically a dinosaur, but it’s very closely related to the common ancestor of all dinosaurs, which would have looked similar: tiny, fuzzy, warm-blooded, and insectivorous.

J is for Judiceratops

Named for the Judith River Formation in which it is found, Judiceratops was an early chasmosaur (relative of Triceratops). By the end of the Cretaceous Period, ceratopsians (horn-faced dinosaurs) were very diverse and abundant across North America, with many similar species coexisting. They all exhibited different flashy headgear, some of which was so paper-thin it must have been for display only, rather than defense.

K is for Kulindadromeus

This little herbivore made headlines as the first non-bird-lineage dinosaur fossil known with preserved complex feathers. However, its feathers weren’t structured like bird feathers, but were instead strange plumes and ribbons. We also know that its back was brown while its lower legs were more reddish, and we know the exact arrangement of its tail scales!

L is for Leaellynasaura

This little herbivore holds the record for the longest tail to body ratio in dinosaurs. It lived in the forests of Antarctica back before it was frozen over; while not as cold as today, it would have still been sub-freezing in the winter, and there would have been six months of polar darkness. To deal with that, Leaellynasaura had lots of insulating fluff and huge eyes for seeing in the dark.

M is for Microraptor

This “raptor” dinosaur was not only crow-sized, but crow-colored: we know that it had iridescent black feathers. It wasn’t a bird, but was closely related, and developed flight independently from the ancestors of birds. Microraptor had flight feathers on both its arms and its legs, making it look like a Star Wars X-Wing when it flew.

N is for Nanuqsaurus

Nanuqsaurus was a high-latitude Alaskan relative of Tyrannosaurus. Its name means “polar bear reptile,” and, unlike T. rex itself, which was at least mostly scaly, it likely would have been covered in insulating fluff.

O is for Oryctodromeus

Meaning “digging runner,” Oryctodromeus was the first dinosaur known to exhibit burrowing behavior. A family of them was found fossilized in their burrow, and their hands were moderately adapted for digging. While they were small for a dinosaur, at 20-30 kilograms (50-70 pounds) they would have required quite a large burrow!

P is for Patagotitan

At up to 70 tonnes, this long-necked dinosaur was one of the largest land animals ever to live. However, it’s still dwarfed by the 200-tonne blue whale, which is the largest animal ever to live. Titanosaurs had a perfect storm of traits that allowed them to get so big: efficient birdlike flow-through lungs, hollow birdlike bones, graviportal columnar legs, and egg-laying (giving live birth to a multi-tonne baby that gestates for years isn’t a great survival strategy).

Q is for Qianzhousaurus

Nicknamed “Pinocchio Rex” because of its close relation to T. rex and its long nose, this dinosaur was one of the last, living right up until the asteroid impact. Its name is pronounced “chee-an-jo-sor-us”.

R is for Rajasaurus

While, at the end of the Age of Reptiles, the Northern Hemisphere boasted the famous tyrannosaurs, the Southern Hemisphere’s top predators were the abelisaurs, a family of short-snouted, fast-running dinosaurs. In contrast to tyrannosaurs, which killed with a crushing bite, and carcharodontosaurs, which killed with a slicing bite, abelisaurs had a grabbing bite and would wrestle their prey to death, similar to a big cat today.

S is for Supersaurus

While not the heaviest animal by a large margin, Supersaurus, with its super-elongated neck and tail, was the longest animal ever to live. Did you know that each of your nerves is a single looong cell? Supersaurus probably also had the longest cells ever; its recurrent laryngeal nerve (the one that controls the vocal cords) would have been 25 meters (80 feet) long!

T is for Tianyulong

This little dinosaur is known from a fossil that preserves porcupine-like quills! An ancient lineage, heterodontosaurs were among the smallest of the non-bird-line dinosaurs, and had angry eyebrows and pointy teeth despite being herbivorous.

U is for Udanoceratops

Ceratopsians (horn-faced dinosaurs) weren’t always so huge and ornamented. They started out as small generic bipeds with a slight extension of bone over the neck, which grew over evolutionary time to become the iconic neck frill. Udanoceratops was a late surviving member of that basal offshoot, and it was weirdly big compared to others in its family.

V is for Vallibonavenatrix

Spinosaurs were another group of non-bird dinosaurs adapted, unusually, for a semi-aquatic lifestyle. They had croc-like faces good for catching fish, legs far back on their bodies for propulsion like a boat, and tall, newt-like tails. They were also among the largest carnivores ever, with Spinosaurus probably just edging out Tyrannosaurus and Giganotosaurus for the title.

W is for Wiehenvenator

While to me the most interesting dinosaurs are the ones that are the most specialized, with the weirdest and most extreme adaptations, the generalists and transitional forms deserve recognition as well. One of those are the megalosaurids, large, generic carnivores common in the Jurassic Period. Wiehenvenator and others are in the family that would eventually lead to spinosaurs, which are way cooler. The word root -venator means hunter in Latin, while -venatrix means huntress.

X is for Xiyunykus

Alvarezsaurs were small insectivores adapted for digging into wood and soil in search of bugs. They were probably nocturnal, and had a terrific sense of hearing. While Xiyunykus (“she-you-NYE-cuss”) was a basal member with three fingers per hand, later alvarezsaurs only had one beefy finger.

Y is for Yulong

Oviraptorosaurs (including the famous Oviraptor) were very birdlike omnivores that came in sizes ranging from the robin-sized Yulong to the rhino-sized Gigantoraptor. While they probably wouldn’t’ve turned up their beaks at the chance to steal an egg, the incident Oviraptor was named for was actually a case of protecting its own nest.

Z is for Zalmoxes

The family including duck-billed dinosaurs wasn’t only large quadrupeds–it included many small, swift bipedal dinosaurs as well. Some of these, including Zalmoxes, had teeth like garden shears for cutting tough plants like, well, garden shears.

You’ve made it to the end! If you liked that, I’ve made it into a tiny book. You can get it here: