It’s been awhile since my last update on the status of the coin-operated crow feeder. Life’s been pretty busy, but that’s no excuse–there are crows to feed!

(Find Part 1 here.)

Gauging the crows’ preferences

Last time, I stated that I would provide birdseed for a penny, mealworms for a nickel, cat food for a dime, and peanuts for a quarter, but my naturalist friend pointed out that I don’t actually know the crows’ preferences. So, I set out samples of each on my balcony and observed to see who would come and eat what, in what order.

Turns out I was basically correct–crows took the peanuts almost instantly, although that might have to do with familiarity rather than preference. Once they were used to the cat food, which was presumably something they’d never seen before, that also became pretty popular. The mealworms were a favorite of smaller passerines like juncos, chickadees, titmice, and finches. Almost nobody likes the birdseed–they’ll only eat some of it, and only when it’s the only thing left.

It was interesting to compare the behavior of different birds. This titmouse didn’t care at all that I was looking at him, or didn’t notice; house finches often come for the birdseed but fly off at the slightest movement I make.

The crows were mostly very skittish as well, and it was hard to get a picture of one. This one was a little braver than most, and took a few pieces of cat food knowing I was watching. He was in a big hurry though, and ready to take off at any moment. Mostly when I put out cat food and am watching it, the crows will gather in the large oak tree across the driveway to surveil the spot, and will only approach the balcony when I’m not looking.

After many days, this house finch got used to me enough for me to take some pictures of him.

And then finally he was confident enough to bring his wife!

I love the fact that even though it took him many days to get used to me enough to stay put when I moved, the wife was okay with my presence immediately, because she trusted her husband’s judgment.

Construction

“Measure nonce, cut once,” that’s my motto…and yes, it turns out about as well as you’d expect. I cut pieces out of an old crate using a jigsaw and nailed them together to make this crappy box. It’s surprisingly sturdy though, and will work for what I’m planning to do with it.

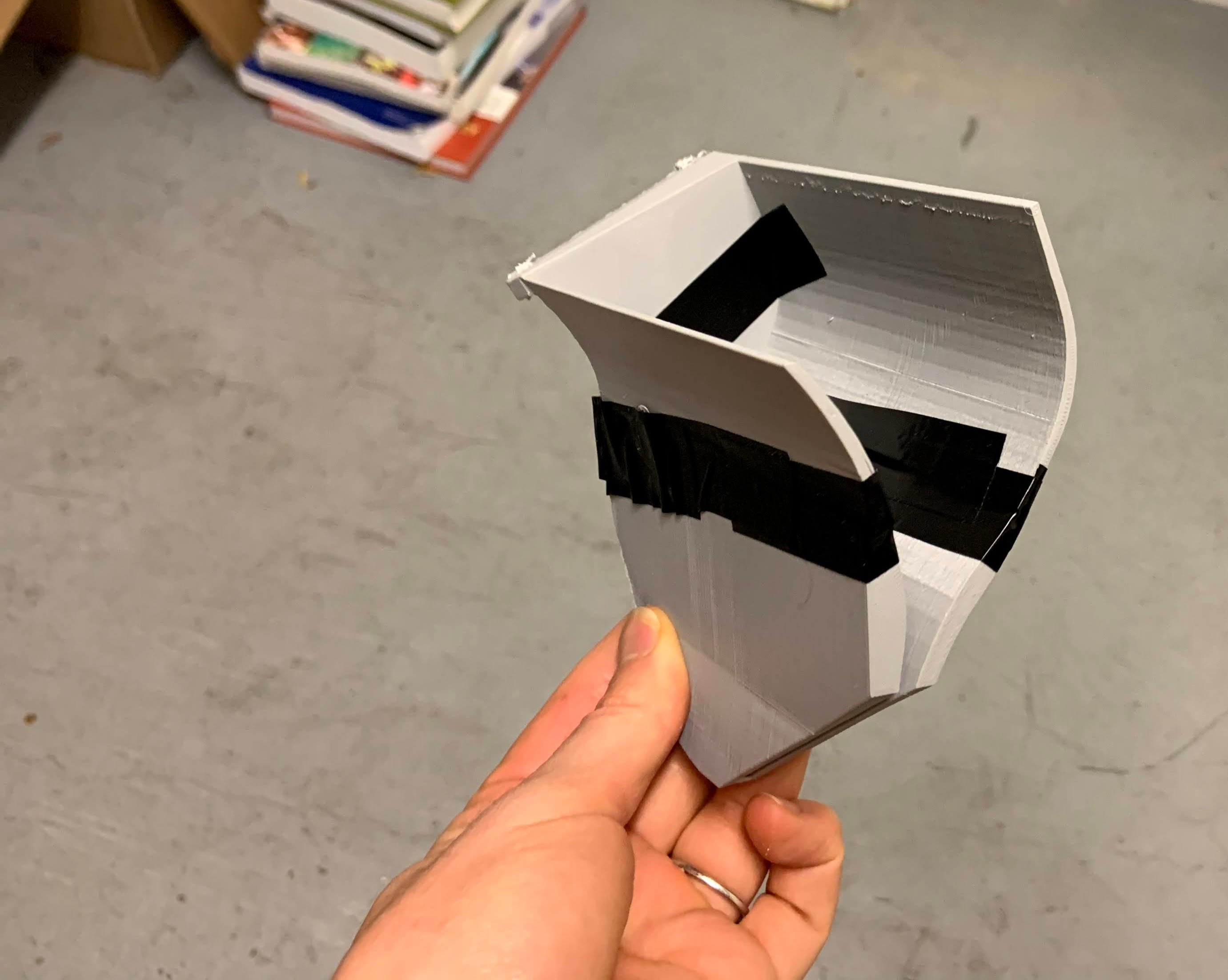

My brother has a 3D printer, so I had him print me this complicated-shaped pre-filter. The idea is that it will allow non-slot-shaped things to roll off, preventing the mechanism from getting clogged with rocks and debris.

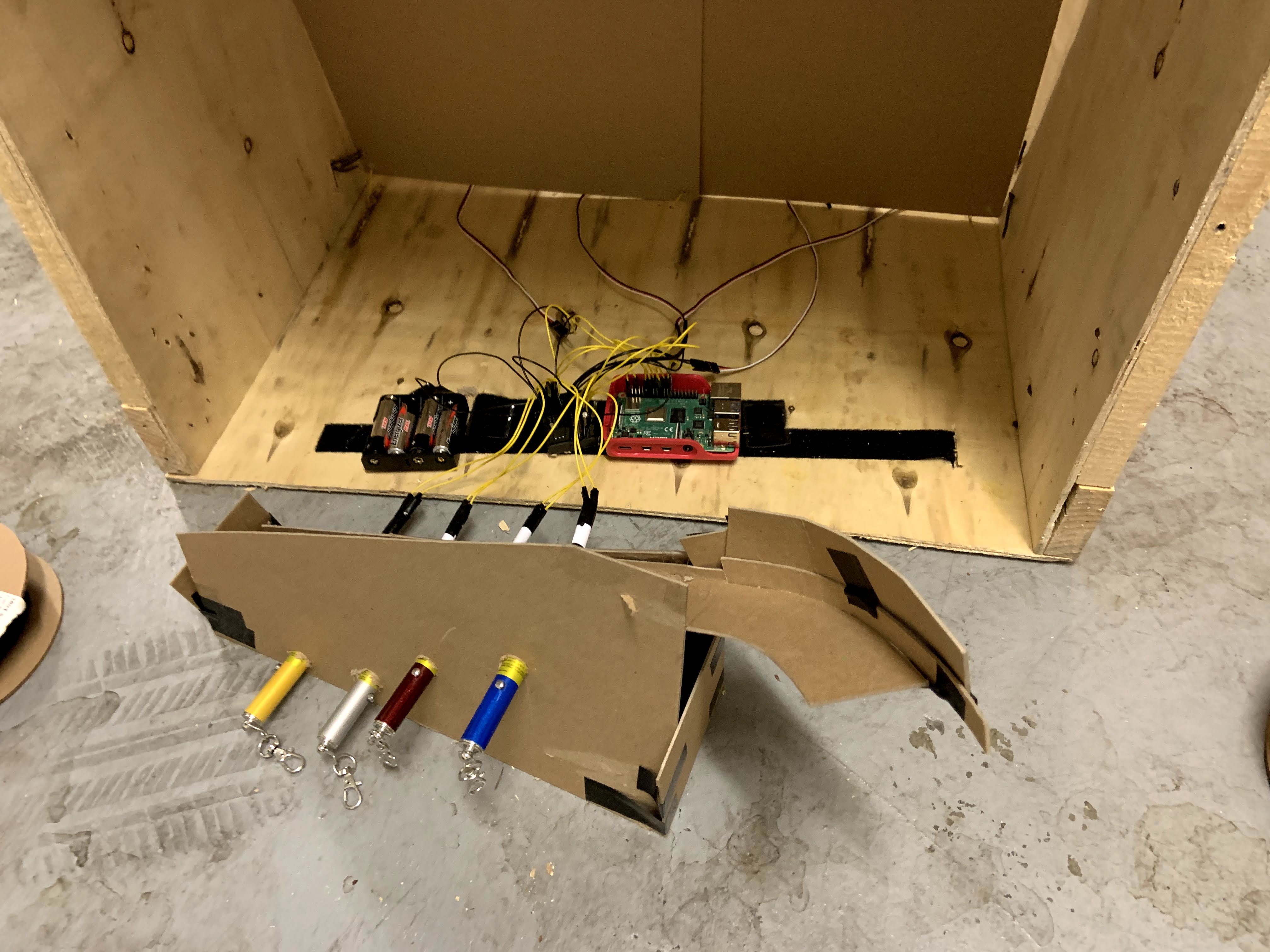

The next step was to assemble the lasers and photoresistors to the sorter ramp.

I suspect that getting these to work reliably will be a pain. We’ll deal with that when we get to it. I also mounted the computer, battery pack, and breadboard to the back wall using Velcro.

Here’s where I am finally forced to admit that this super quick-and-dirty approach is probably not going to work. I wanted to use more Velcro to mount the servos to the back wall so that I could reposition them easily, but they’re sagging so much that it looks like they won’t stopper the bottles effectively. I could try to prop them up or something, but I think I’m going to need to actually get some standoffs and mount these things for real.

By the way, I switched to Gatorade bottles for two reasons: the wider necks keep the larger food items from clogging, and that smaller-diameter portion of the bottle makes a very convenient mounting location.

Debugging

Back at the debugging station, I’m finding more issues. The photoresistors are actually surprisingly robust at detecting the laser light even when the laser isn’t pointed straight down the tube, but the coins, especially the smaller ones, often go by too quickly to be detected. Sticking a finger in to block the beam is detected without fail, but a penny or dime falling past fails to be detected.

The first solution I tried was adding a flap that a coin could hit to help occlude the light, but it turns out that dimes are so small that they have trouble moving even a piece of paper, and I didn’t think paper was robust enough to use even by my low standards of craftsmanship. The next thing I tried was to adjust the “LightSensor” Python class I’m using to be more sensitive to darkness. There’s a parameter for that, but unfortunately playing with the value of this parameter still failed to get the small coins detected consistently. Plus, after having the lasers powered on continuously for 24 hours, they were starting to look quite dim. Overall, I don’t see this ramp mechanism working. Time to change gears!

A new approach: the scale

Has anyone heard of Bottomless, the coffee subscription service? They send you a little Wifi-enabled scale that you set your coffee bean bag on, and when the bean level gets too low they automatically send you another. My fiancé was an early adopter, and received a janky 3D printed scale when we started our service. Later, Bottomless sent us an upgraded, professionally fabricated scale, so the 3D printed one was just sitting around. Mottainai! Better repurpose it into something useful. Can I use the difference in weight between the types of coins to make a more robust coin acceptor?

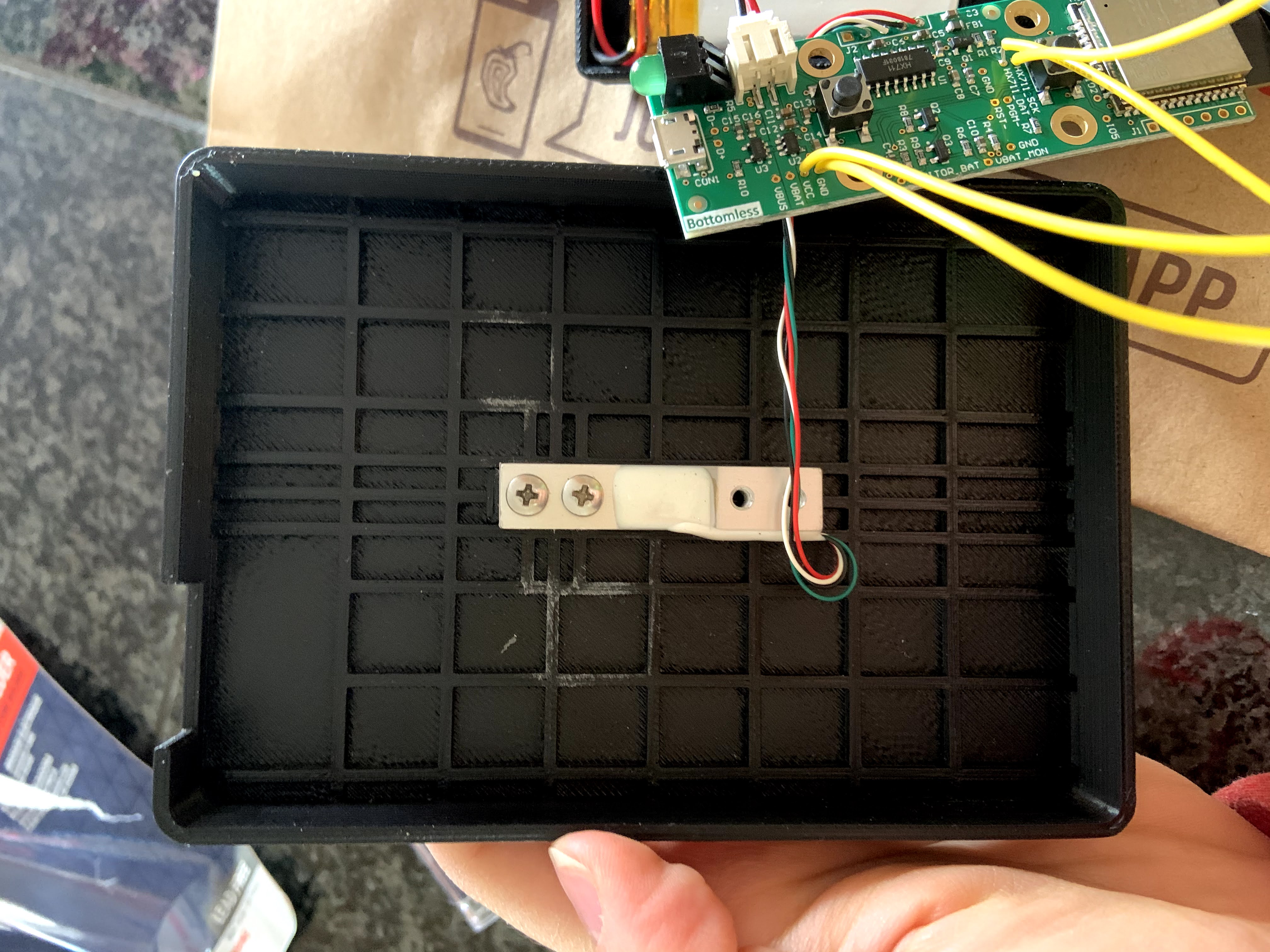

Opening up the little scale, we find just three components: a load cell, a battery, and a printed circuit board.

A load cell is a very cheap, very robust weight sensor. It’s made of a metal piece with some holes drilled in it to make it more flexy, and some strain gauges on two sides of it hooked up in a clever way so that it’s accurate regardless of temperature or other conditions.

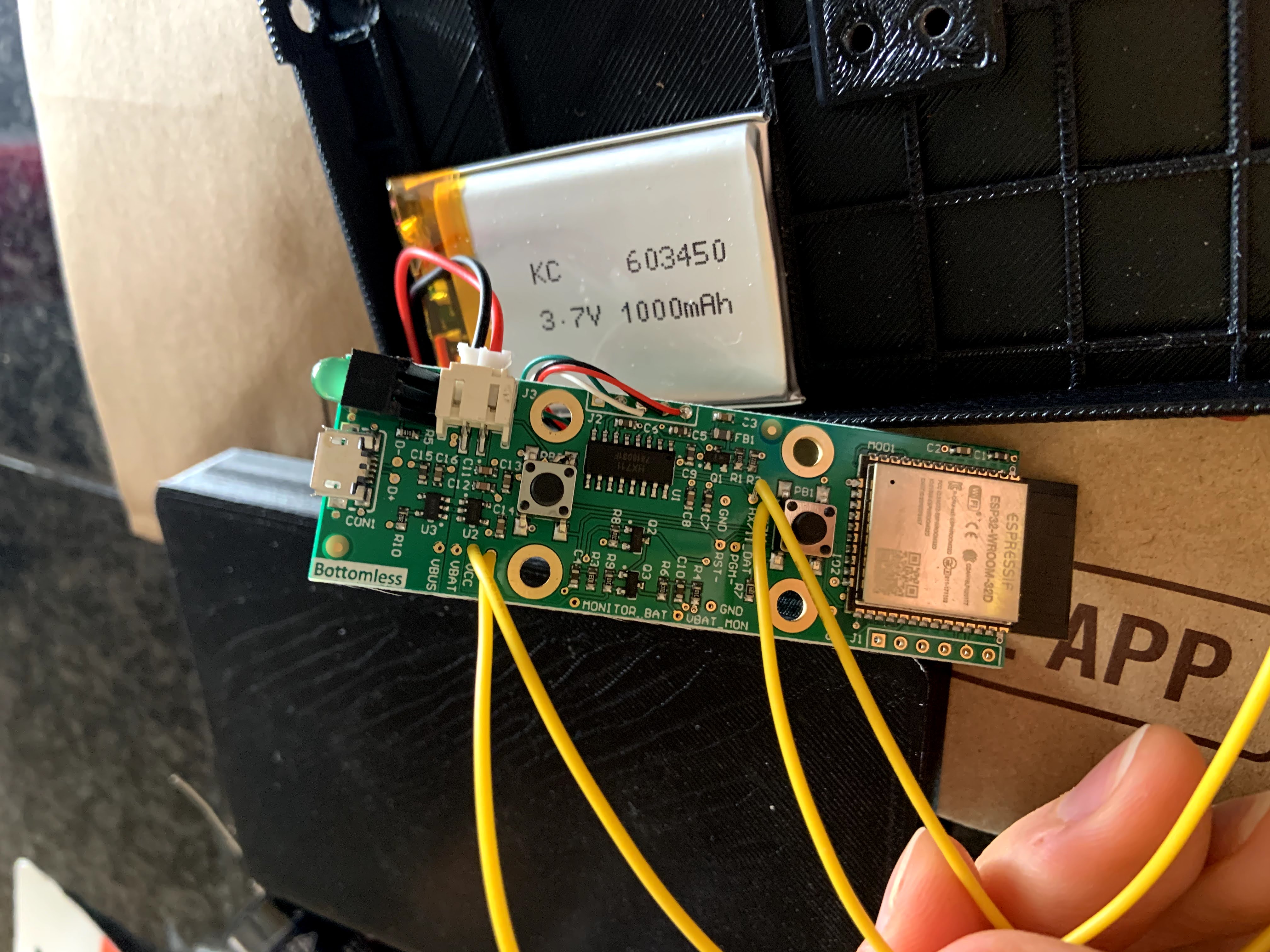

Here’s the board, which has two main components: the analog-to-digital converter (called HX711, the large black rectangular chip in the middle), and the Wifi module (called Espressif, the huge square silver chip at the bottom). I don’t need the Wifi capabilities and don’t really care if they’re running. Luckily for me, the board has the signals I do need–the HX711’s clock and data signals, and the voltage and ground–broken out into conveniently labeled plated through-holes. All I needed to do was cut the ends off some of my jumpers and solder them to those holes, and it’s ready to be connected to the Raspberry Pi!

Whoops, while messing with the scale, I snapped off one of the load cell wires. Then, when I soldered it back on, I must’ve electrostatically fried something, because the load cell stopped reading anything but “-1”. Guess I need a new one. Good thing the load cell plus HX711 is only $8 on Amazon. But so much for upcycling!

A few days later

Nice, now I’ve got the new scale working and I’ve written the Python program to detect coins. All I need to do now is get the hardware to mount everything up and I’ll be ready to deploy.

You can see the new HX711 board suspended by its wires above the Pi, and the new load cell with Reese’s Puffs receptacle. The HX711 is a lot smaller than the Bottomless scale’s board (since it’s missing the Wifi, LED, etc) but the load cell is much larger. A happy accident, since that makes it easier to work with. I gave up on using the 3D printed slot funnel because coins kept getting stuck in it, and it’s also less important for the weight detecting scheme than it was for the ramp-sorting scheme. If the crows happen to put debris into the hole in amounts exactly equaling the weight of a coin, good for them. It won’t clog the mechanism, so it’s not worth the trouble.

I had to modify the position of the load cell and the way the receptacle was mounted a few times (I thought the ratio setting portion of my software was calibrating out the lever arm, but it wasn’t; the load cell assumes the center of gravity of the load is directly above the hard mounting point) but eventually got everything to work together. Of course nothing ever works right the first time!

I recently moved to San Francisco, to an apartment building with a super strict HOA that definitely would not appreciate an ugly box like this sitting around. (They have a 70-page manual on what you’re allowed to do as a resident. The only things you can display in your window are a cloth American flag or tasteful plants.) So, I’m going to leave this at my parents’ house (my mom is thrilled /s), and since they have wildlife capture cameras set up around the house I’ll be able to see when crows come to interact with it.

I installed the box on a fence in my parents’ yard, to keep it out of reach of deer and turkeys. I anticipate having issues with squirrels and bees, but we’ll see. I put some clear plastic over the parts I don’t want the animals messing with.

Unfortunately, the conditions outdoors make the scale readings much more variable than they were indoors. That meant I had to widen my acceptable weight ranges, which, in combination with the removal of the slot-shaped filter, means that the feeder will accept anything even close to a coin in weight. I’m hoping that I can still make progress training the crows to put things into the feeder while I figure out how to solve this issue, though.

I expect crows to take a long time–maybe up to a couple years–to get used to the box and the weird servo noises, and I’ll post Part 3 when I’ve made some progress on that front. I’m also starting a new job next week that will allow me more access to better 3D printing capabilities, so now that I know how everything is physically mounted in my prototype, I can get started on redesigning various elements for robustness, and hopefully switch this crappy wooden box out with a sleek plastic version sometime down the road.

Thanks again for reading!