Moving back toward some more characteristic material this week. Sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs) were a weight class of land animal the world has never seen before or since, and they’re woefully underrepresented on this blog. Not only were they objectively top tier, being one of the earliest dinosaur lineages to arise and having a worldwide distribution throughout the entire Mesozoic, they displayed a wide diversity of forms and adaptations during their long reign. In this post I’ll discuss a selection of a few particularly interesting sauropod genera.

Diplodocus

Family tree: Dinosauria > Saurischia > Sauropoda > Diplodocoidea > Diplodocidae

Hometown: North America, 154-152 million years ago (Late Jurassic)

Discovered 1877, described 1878

Okay, Diplodocus is not what one would consider an obscure dinosaur, but I aim to provide some obscure facts about this well-known dinosaur later in this section. But first, the basics. This sauropod from the Late Jurassic of the Morrison Formation (Colorado and surrounding states) is one of the best-understood dinosaurs, known from numerous specimens that preserve every part of the body, including skin impressions, except, for some strange reason, the skull. (However, skulls are known from very closely related species such as Galeamopus, so we can get an idea of what Diplodocus’s skull would have looked like.) While it wasn’t the longest or heaviest sauropod ever, it was still quite impressively large, clocking in at 24 meters long and up to 15 tonnes. (Late Cretaceous giant titanosaurs like Argentinosaurus could reach 30 or 40 meters in length and 75 tonnes in weight.) Diplodocus existed at the height of sauropod diversity, living alongside lots of other huge sauropods such as Barosaurus, Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Brontosaurus, which all would have specialized on different food sources and eating styles so as to reduce competition. Diplodocus was featured in the Jurassic episode of Walking With Dinosaurs, a depiction that’s aged very gracefully and is definitely worth a watch. I’ll go over the different behaviors and attributes depicted in that episode and discuss which are known, which are hypothesized, and which are just fanciful as we move through this section.

How do you pronounce “Diplodocus,” anyway?

“Dip-PLOD-uh-cus” and “Dip-lo-DOH-cus” are both acceptable, but I (and many people I know) prefer the former. However, for the group names Diplodocoidea, Diplodocidae, and Diplodocinae, putting the emphasis on the “doh” makes them roll off the tongue a bit easier. It’s inconsistent, but hey: taxonomic names often combine roots from all kinds of languages in one word–not just Latin and Greek, but Chinese and even Navajo and others–so trying to be consistent on top of that basis is probably futile.

What and how did it eat?

Diplodocus had a long, horselike face with simple pencil-shaped teeth only in the front, which it would have used to strip leaves from branches by biting close to the base and pulling its head back. This is in contrast to other sauropods’ feeding styles such as chomping (just ingesting the whole branch) and grazing (specializing on vacuuming up low vegetation). Young Diplodocdus had shorter skulls with teeth further back in the jaw, indicating a different feeding style than the adults as well. This makes sense, as the juveniles were comparatively tiny and would not have been able to strip tree branches.

How did it grow and reproduce?

In Walking With Dinosaurs, a mother Diplodocus is shown using an ovipositor, or egg-placing organ, to lay her eggs carefully in a hole without having to bend down to avoid breaking them. This isn’t impossible, but we don’t have any evidence for ovipositors in dinosaurs, and we now know that at least some sauropods laid soft-shelled eggs that could have survived a longer fall. However, the documentary got the basics right: Diplodocus, similarly to most sauropods, would have laid a large clutch of small eggs and provided no parental care at all, and only a minority of eggs would’ve survived to adulthood. These conclusions are supported by a few lines of evidence: fossilized nests from a variety of sauropod genera across time show large clutch sizes of up to 40 eggs, and the ridiculous size difference between hatchlings and adults (palm-sized versus Airbus-sized) would have made parental care difficult.

Above: My Technicolor depiction of Mussaurus, an early sauropodomorph, showing the vast difference in size between a hatchling an an adult. This was the M.O. of sauropods. The hatchling may be about to get trampled.

In addition, groups of juvenile Diplodocus have been found preserved together, lending support to the hypothesis that animals of similar age would form “creches” for safety in numbers.

Did it really have spikes?

Fossilized skin impressions show that Diplodocus had thin, keratinous spikes along its back and on the end of its tail, sort of like an iguana. The ones on the end of the tail could have increased the damage dealt by a whipping attack, or they could have been simply for display. In addition to the well-known fossilized spines from 1990, new extensive skin impressions have been unearthed just last year, showing a variety of scale shapes.

Speaking of the tail, it’s often been hypothesized that Diplodocus and other related long-tailed sauropods could have made loud cracking noises by whipping their tails so fast they broke the sound barrier. While theoretically possible (as shown by a scaled-down, hand-operated model that can indeed crack like a whip) it’s not known whether the animal could have moved its tail this fast, or how the tissues at the tail’s end would have held up under such forces.

How did it hold its neck?

Sauropod neck posture has long been a hotly debated issue, with some scientists claiming certain dinosaurs couldn’t lift their heads higher than their shoulders and others promoting a swan-like S-curve. Diplodocoids in particular are often depicted with their necks stretched out horizontally in front of them, both because their front legs were shorter than their back legs, and because that’s the centered position of the neck vertebrae’s range of motion. However, more recently, biomechanical models have become better at accounting for cartilage and soft tissue, whose inclusion tends to increase the model’s flexibility, and more in-depth studies of living animals show that nearly all of them habitually hold their necks at one extreme of the possible range of motion, not in the center. These results indicate that even diplodocoids probably held their necks at least somewhat elevated.

Above: Mark Witton’s 2018 depiction of a Diplodocus herd, exhibiting an elevated neck posture. You can read more about the decisions that went into this artwork in his blog post.

The authors of the paper examining living animals’ neck posture I referenced above have been so enthusiastic about spreading the gospel of vertical sauropod necks that they’ve devoted an entire blog–yes, a whole blog, not just a blog post–to the topic.

Were males and females different from each other (sexually dimorphic)?

One intriguing and oft-cited phenomenon is that about half of Diplodocus specimens (and half of Apatosaurus and a quarter of Camarasaurus specimens) have some of their proximal tail vertebrae fused together. Anything that occurs to 50% of the population is a candidate for being explained as sexual dimorphism, so numerous hypotheses have been proposed as to what these fused vertebrae were used for. Perhaps they strengthened the female’s rear end so she could support the male’s weight during mating, or perhaps they allowed the female to lift her tail out of the way of mating. Maybe it was the males that had the fused vertebrae and they used them to support the musculature needed for tail-cracking displays. Or maybe it was the older individuals, whose vertebrae fused over time because of the loads the tail experienced from contacting the ground when the animal reared up into a tripod stance.

While all of these suggestions sound plausible, there are a few important caveats to note here. One is that “fifty percent of Diplodocus specimens” sounds like good evidence for sexual dimorphism, but “three out of six Diplodocus specimens” doesn’t have much statistical power. Maybe eighty percent of specimens had fused vertebrae and we just got an unrepresentative sample preserved by chance, or maybe it was a genetic disease shared by this one family that was fossilized together. Furthermore, not all animal populations have an equal number of males and females, and even if they do that ratio might not make it into the fossil record. And Camarasaurus was a macronarian, with very different body proportions and lifestyle than diplodocids, so a parsimonious explanation of the vertebral fusion has to involve a behavior generic to all sauropods. So, in summary, we don’t know.

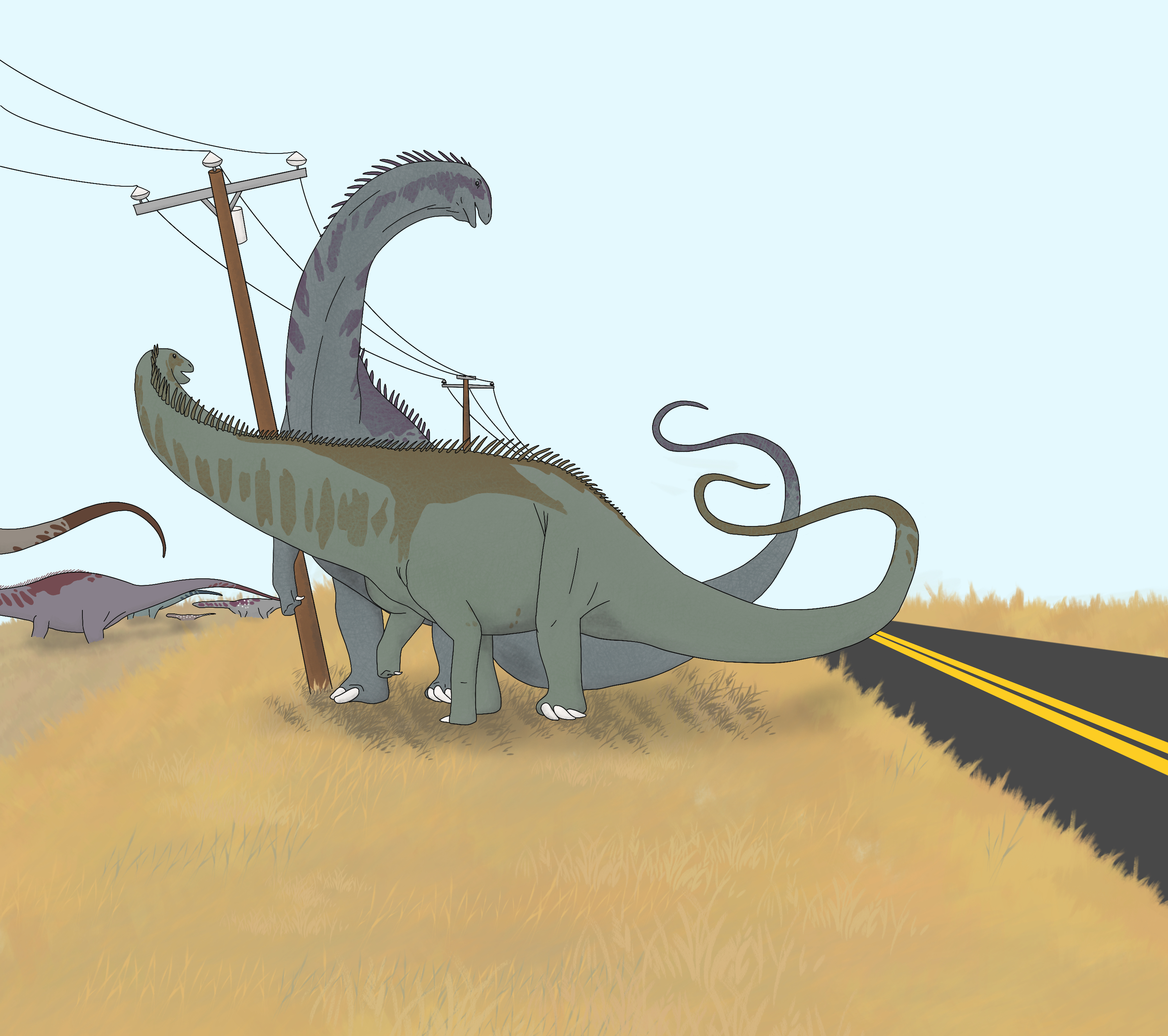

What’s with the page image?

I saw a pencil sketch by u/SandHanitizer55 on Reddit that depicted two Diplodocus engaged in a shoving match near a highway and some power lines. I thought it was a really fun, fanciful idea, so I digitally colored it. It’s fun to imagine what the world would be like if certain extinct animals were still around. Flocks of migrating giant pterosaurs blocking out the sun? Theropods menacing ranchers’ herds, and hunters mounting Tyrannosaurus heads on their walls? Ornithopods pulling plows and oviraptorosaurs being kept for giant eggs?

Bajadasaurus

Family tree: Dinosauria > Saurischia > Sauropoda > Diplodocoidea > Dicraeosauridae

Hometown: South America, 145-133 million years ago (Early Cretaceous)

Discovered 2010, described 2019

We’re back in obscure dinosaur territory, with the recently described and extremely charismatic Bajadasaurus, known from just one specimen with a well-preserved skull and a couple vertebrae. Compared to Diplodocus and its contemporaries, dicraeosaurids like Bajadasaurus were diminutive, at only 9 or 10 meters long and up to 3 tonnes–the size of a smallish elephant. They also had relatively short necks, for a sauropod, and would have grazed on low plants.

While all members of Dicraeosauridae had long neural spines (the tall dorsal part of their vertebrae), only Amargasaurus and Bajadasaurus had super-elongated spines that would have been enclosed in horny keratin sheaths. And, strangely, Bajadasaurus’s and Amargasaurus’s spines faced opposite directions, with the latter’s pointing back toward the tail. If the spines’ purpose was to protect the neck while the animal’s head was lowered to graze, forward seems like a better spine orientation to me; but since Amargasaurus shows the opposite, perhaps they were purely for display. Or, maybe Amargasaurus was more concerned with being attacked from behind?

Another interesting feature of Bajadasaurus is the fact that its eyes were situated near the top of its head, allowing it to look forward stereoscopically when its head was bowed.

Brachytrachelopan

Family tree: Dinosauria > Saurischia > Sauropoda > Diplodocoidea > Dicraeosauridae

Hometown: South America, 160-150 million years ago (Late Jurassic)

Discovered and described 2005

Another dicraeosaurid (close relative of Bajadasaurus), we have the extremely short-necked sauropod, Brachytrachelopan! Sauropods are the group most famous for their long necks, and this one decided that was totally mainstream.

I like this little sauropod because it’s filling the niche of an ornithopod (“duck-billed dinosaurs” and their relatives). Convergence is so cool!

Magyarosaurus

Family tree: Dinosauria > Saurischia > Sauropoda > Macronaria > Titanosauria

Hometown: Hațeg Island, 71-66 million years ago (Late Cretaceous)

Discovered 1895, described 1915

Speaking of tiny sauropods, here’s the pint-sized Magyarosaurus, a denizen of the enigmatic Hațeg Island. Insular dwarfism is a phenomenon in which populations of animals isolated on islands become a lot smaller than their mainland relatives, due to scarcity of island resources. (Sometimes the opposite happens, and small prey animals become giant on islands due to lack of predators, creating humorous situations in which elephants are the same height as geese.) The one-tonne Magyarosaurus was closely related to the ten-tonne mainland Rapetosaurus.

In the Cretaceous, Hațeg Island, Romania was populated with cow-sized sauropods and nodosaurs, dog-sized ornithopods, and the giant plane-sized pterosaur Hatzegopteryx, which was the apex predator of the ecosystem.

Above: A somewhat clichéd reconstruction of giant pterosaurs stalking dwarf sauropods. In reality, Hatzegopteryx would only have preyed on juvenile “sauropodlets” and other small prey; adult Magyarosaurus were outside its pay grade.

Shunosaurus

Family tree: Dinosauria > Saurischia > Sauropoda

Hometown: China, 159 million years ago (Late Jurassic)

Discovered 1977, described 1983

Last but not least, we have Shunosaurus, whose relationship to other sauropods is somewhat disputed. It was pretty small, at 3 tonnes, and pretty short-necked, though neither as extreme as the above-described Brachytrachelopan, but its claim to fame is being the only known sauropod with a tail club! While a more impressive version this weapon came standard on ankylosaurs, glyptodonts (giant armadillos), and meiolaniid turtles, it’s pretty cool that sauropods entered a contestant too.

That concludes our whirlwind tour through an eclectic collection of sauropods! I hope you have a better appreciation of sauropod diversity. They weren’t all just long-necked giants, but filled a variety of ecological niches both familiar and no longer extant. I’ll probably do some more posts on sauropods in the near future, so stay tuned!

Image Credits

Original page image Mark Witton’s Diplodocus Bajadasaurus 1 Bajadasaurus 2 Brachytrachelopan Magyarosaurus Shunosaurus