The Pokémon franchise takes a lot of inspiration from the natural world, including extinct plants and animals. While many of its designs are fanciful and some of its flavor text unscientific, I’d say in general it does a service to the life sciences, and judging from what kinds of people are fans, it seems I’m not alone in this opinion.

In this post I’ll go over the different Pokémon that are inspired by extinct organisms–there are quite a few more than just the obvious Fossil Pokémon–and discuss the scientific accuracy of the portrayal and what may be the inspiration for certain features.

I actually wrote this post before I heard about the Pokemon Fossil Museum, a new touring exhibit opening in Japan this summer. I guess Nintendo and I are on the same wavelength. If I can get details about what the exhibit is like (or if it comes somewhere near me) maybe I’ll do a follow-up post on that.

Avalugg

I’m going to start with a few Pokémon whose paleontological inspiration is less obvious. Avalugg is clearly inspired by an iceberg, but it’s an iceberg crossed with an extinct, herbivorous crocodile relative called Desmatosuchus.

Desmatosuchus was an impressively tabular aëtosaur, one of a subset of the croc family that were heavily armored, low-slung herbivores, similar in niche to the later ankylosaurs and glyptodonts. They had upturned snouts they may have used to dig for roots, like boars. Aëtosaurs, like many diverse forms of pseudosuchians, rose and fell within the Late Triassic.

Dreepy, Drakloak, and Dragapult

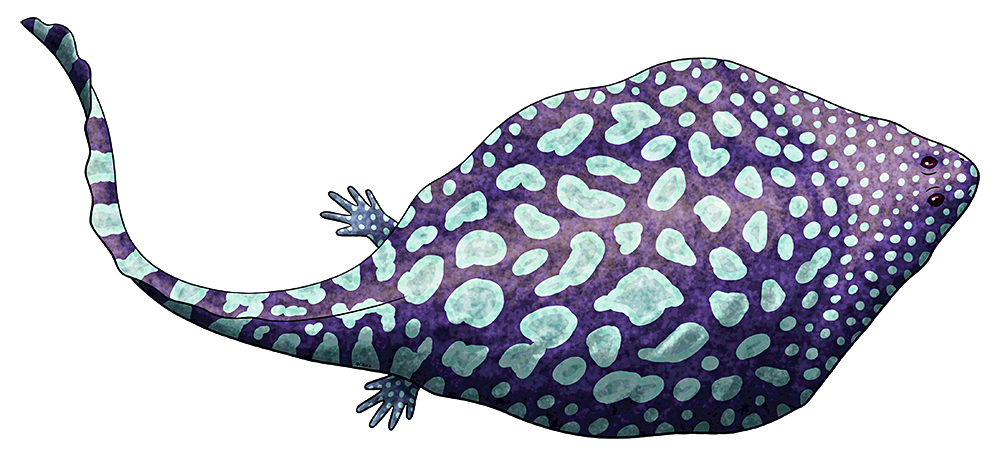

This is another case of crossing an extinct animal with an inanimate object: the stealth bomber-slash-Diplocaulus, Dragapult! Diplocaulus was an amphibian from the Late Carboniferous and Permian that had a boomerang-shaped skull. Dragapult’s appearance is based on older reconstructions, which depicted a shrink-wrapped boomerang:

But lately, artists have been moving toward a more stingray-like body shape, showing the boomerang prongs as supports for soft tissue:

I like how the first form of this Pokémon, Dreepy, emphasizes the amphibian inspiration by having no legs, like a tadpole. While this is probably the first canonically amphibian Dragon-type, some people have decided that Dragonite may be another example:

I hope no one’s childhood has been ruined by this. I’m actually a big fan of this interpretation. It even explains what those earlike things on Dratini and Dragonair’s heads are: axolotl-like external gills!

Bulbasaur, Ivysaur, and Venusaur

Here’s a case not where Pokémon was inspired by paleontology, but where paleontologists were inspired by Pokémon: the dicynodont (mammal relative) Bulbasaurus, named after Bulbasaur. (The species name, phylloxyron, means “leaf razor,” after the move Razor Leaf.)

There has been long-standing debate over whether the Bulbasaur line are frogs, lizards, dinosaurs, or something else. While I believe Nintendo probably meant for them to be a reptile of some sort, they do coincidentally have a lot in common with dicynodonts. They have what appears to be a plant-cropping beak and no teeth other than two long canines that protrude from the mouth (Venusaur has an additional four lower teeth, but Bulbasaur and Ivysaur only have the two). They also have what appears to be mammal-like external earflaps, which, to be fair, are not something any of the above-mentioned groups had, probably even dicynodonts, but dicynodonts are the most closely related to the group that does. So, the question is still unresolved as to what exactly these Pokémon are supposed to be, but dicynodont does seem to be a valid option.

Dicynodonts, including Bulbasaurus, were a group of mammal-relatives from the Late Permian period. They had a semi-sprawling stance and came in a range of sizes, from gopher to elephant (Bulbasaurus was on the smaller end, with a skull 14 centimeters long). They developed endothermy (warm-bloodedness) independently of the lineage that led to mammals, which implies that the smaller ones may have been furry. Dicynodonts were very abundant and successful in their time and were one of the few groups to not only survive the Great Dying that ended the Paleozoic Era, but to thrive during and after the transition, only to slowly decline and go extinct by the end of the Triassic.

Relicanth

This one’s easy: it’s literally just a coelacanth (pronounced “SEE-la-canth,” but the Pokémon’s name makes me wonder if whoever at Nintendo named it thought it was pronounced “ko-EL-a-canth” since it rhymes). These lobe-finned fish are famous for being known from Mesozoic fossils prior to being discovered to still be alive. The modern ones look a lot like some of their ancient relatives, leading to them often being called “living fossils” and being described as “not having changed in 100 million years”. (Relicanth has these phrases repeated in its Pokédex descriptions as well, although the reason given for its lack of change is “it’s apparently already a perfect life-form”.)

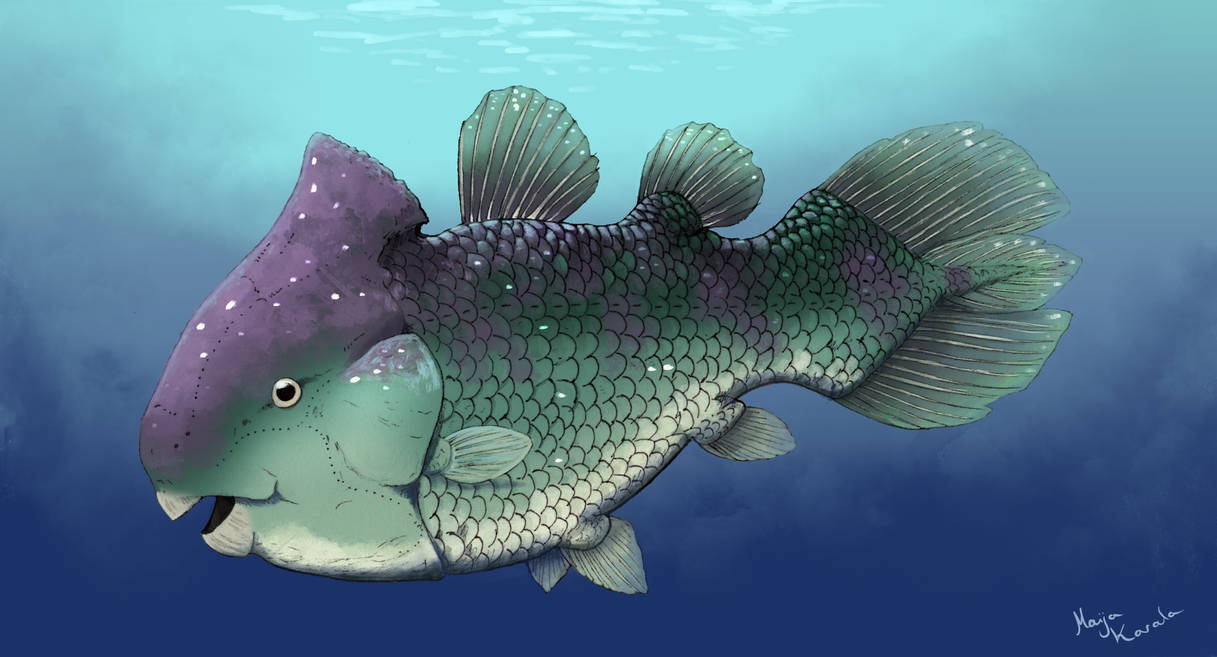

These phrases are a bit problematic in what they imply about how evolution works–in reality, everything is always evolving, but when evolutionary pressures remain similar over long periods of time, animals’ outward appearance can change very little. However, modern coelacanths are as genetically distant from their very similar-looking ancient relatives as we are from our very different-looking ancient relatives. Furthermore, coelacanths have explored some more diverse forms over their evolutionary history, such as the parrotfish-like Triassic Foreyia:

And since we have essentially no coelacanth fossils younger than Cretaceous age, who’s to say our modern coelacanths’ lineage didn’t diverge wildly into some exotic form, only to re-converge to the conservative body plan in time for us to observe it?

For further exploration into these topics, I’d highly recommend the Common Descent Podcast’s episodes on coelacanths and “living fossils”.

Pyukumuku

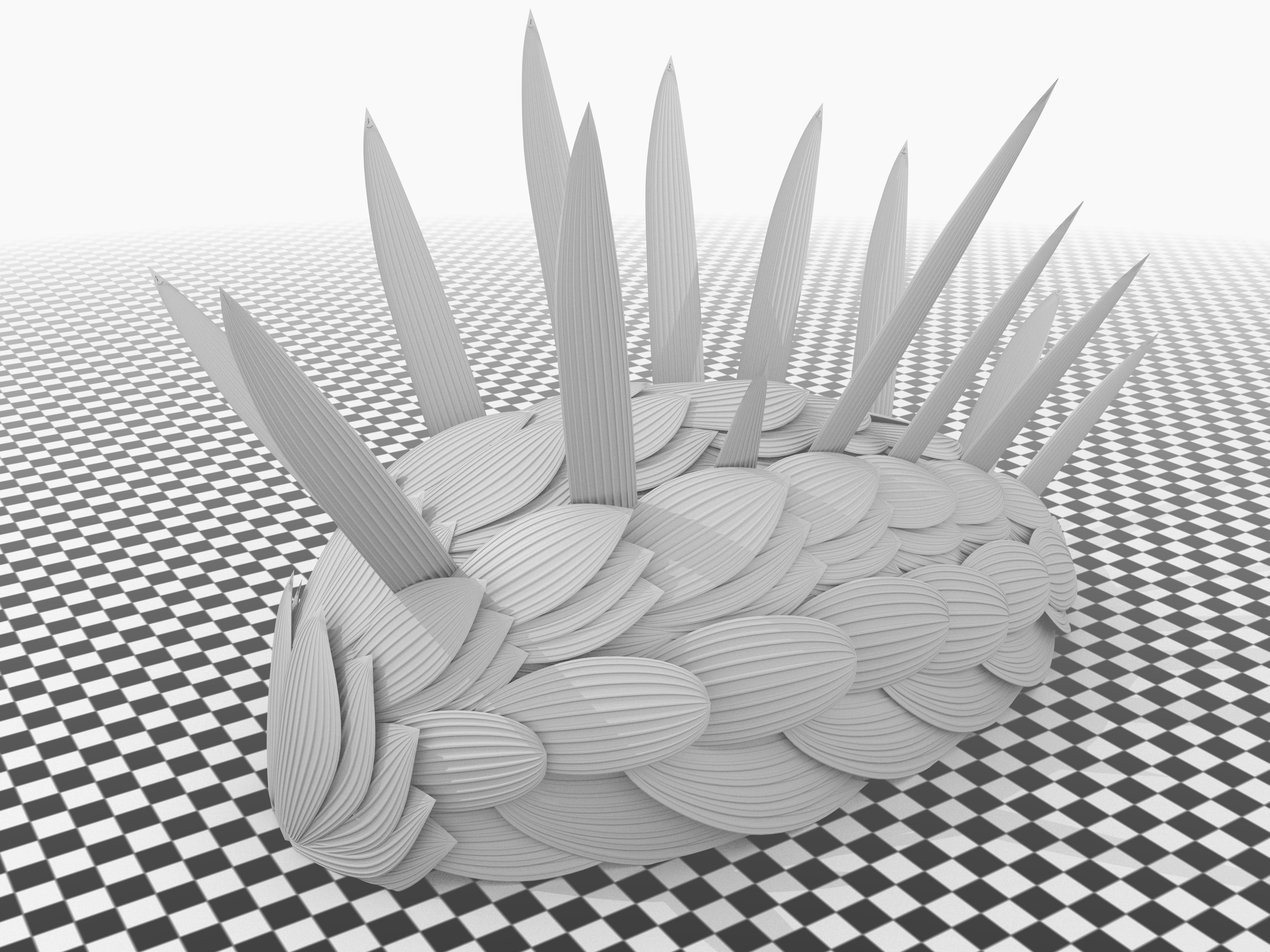

While Pyukumuku’s “gut punching” gimmick is based on a behavior of sea cucumbers in which they expel sticky tubes that are part of their respiratory system out their anus when startled (unlike Pyukumuku the guts don’t go back in, but shed and grow back), Pyukumuku’s overall appearance seems to be based on the Cambrian animal Wiwaxia.

Known from the Burgess Shale, this little stem-mollusc was covered in scales and long spines, probably to protect itself from predators like Anomalocaris (more on that later).

Other vaguely dinosaurian Pokémon

Before we jump into the Fossil Pokémon, I’ll just take a second to list a few others that are possibly based on non-avian dinosaurs. For beautiful artistic interpretations of some of these, check out Arvalis’s Realistic Pokémon series and ShadeofShinon’s Pokédex on Deviantart.

- Chikorita, Bayleef, Meganium: sauropods, or tortoises?

- Tropius: definitely a sauropod

- Jangmo-o, Hakamo-o, Kommo-o: bipedal ankylosaurs, some kind of theropod, or pangolins? (Jangmo-o’s Pokédex entry says its scales are actually “fur that’s become hard as metal”.)

- Axew, Fraxure, Haxorus: basal ceratopsians?

- Aron, Lairon, Aggron: definitely ceratopsians

- Druddigon: maybe a bipedal stegosaur (the “wings” are dermal plates)

- Magby, Magmar, Magmortar: possibly oviraptorosaurs (they have a beak and a long reptilian tail)

- Breloom: maybe a pachycephalosaurid (and Shroomish is an egg)

- Dialga: possibly a stegosaur

Gen 1

We’ve made it to the actual Fossil Pokémon, which are more explicit in their paleontological source of inspiration. They also say some pretty interesting and sometimes incriminating things in their Pokédex flavor-text, so I’ll go into a bit more detail on that here. Gen 1 includes the ammonite-like Omanyte and Omastar, the horseshoe crab-like Kabuto and Kabutops, and the pterosaur-like Aerodactyl.

Ammonites were a type of shelled cephalopod that looked superficially similar to modern nautiluses (think snail shell with a squid face sticking out) but were actually more closely related to the other living cephalopods: octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid. They were a very long-lived group, ranging from the Early Devonian all the way to the Late Cretaceous, finally going extinct in or near the same extinction that killed the non-avian dinosaurs. They came in many shapes and sizes, including the giant Titanites, with a 1.37-meter-long shell, and the knotty-shelled Nipponites and Didymoceras, which look like they would have been so un-hydrodynamic that they shouldn’t’ve been able to swim at all. Omanyte’s and Omastar’s shell shapes seem to be based on that of a classic spiral ammonite, but the fact that they crawl on the ground rather than swimming may be a nod to an even more ancient basal cephalopod such as Plectronoceras:

(My fiancé dubbed this “Wizard Squid”.)

I think most people know that snails and squid are both molluscs, but probably haven’t pictured what a transitional form would look like. This tiny Late Cambrian mollusc had some short, rudimentary tentacles, and had air sacs in its shell it would’ve used to change its buoyancy, mainly hanging out on the ground but able to rise up into the water column to escape predators. Some of Omanyte’s Pokédex descriptions reflect this: “This Pokémon uses air stored in its shell to sink and rise in water.” Nice. The Pokédex also makes mention of predation by Archeops, which checks out since ammonites and early birds coexisted for millions of years, though Archeops hardly seems adapted for a durophagous (shell-crushing) or diving lifestyle. And, it mentions the concept of invasive species: “Because some Omanyte manage to escape after being restored or are released into the wild by people, this species is becoming a problem.” Definitely something worth thinking about when undertaking de-extinction! Perhaps the environment has changed so much in their absence that a return to the old status quo would cause even more problems.

However, where the Pokédex falls a little short in this case is in Omastar’s description: “It is believed to have become extinct because its shell grew too large and heavy, causing its movements to become too slow and ponderous.” This is an example of the early-1900s trope of victim-blaming extinct animals for their own demise. Before the Alvarez hypothesis (the idea that an asteroid caused the end-Cretaceous extinction), many people blamed dinosaurs’ size for their extinction, claiming that they “evolved themselves into a corner”. Similar claims have been made about the Irish elk, Megaloceros, whose antlers became so ridiculously oversized that people thought they must have been its downfall. However, evolution just doesn’t work that way. If a trait is detrimental to survival, it becomes less common in the next generation, so it’s impossible in a stable environment for animals to hit an “evolutionary dead-end”. (If the environment suddenly changes, however, they might find themselves maladapted.)

Kabuto (meaning “helmet” in Japanese) is essentially just a modern horseshoe crab. Its Pokédex entries state that “living examples have been discovered,” and that “it uses the eyes on its back while hiding on the sea floor,” both of which are true of horseshoe crabs (in fact, horseshoe crabs have four pairs of eyes, plus a singleton central eye, for a total of nine eyes, seven on the back and two on the underside!). Kabutops, however, seems to take an evolutionary step back, being more reminiscent of basal horseshoe crabs that looked kind of like trilobites, such as the Carboniferous Euproops:

(If this artist were still selling these, I’d totally buy one. She sells other cool things too though.)

Unfortunately, the game requirement that a Pokémon’s evolved form be cooler than the pre-evolution caused Nintendo to just slap some praying mantis limbs on it, resulting in something noticeably chimera-like and, in my opinion, not very well designed.

Aerodactyl is named after the diminutive but famous pterosaur genus Pterodactylus, and its design is based loosely on generic pterosaurs, with aspects of dragons thrown in. In another case of life imitating art imitating life, a genus of pterosaur closely related to Pterodactylus was named Aerodactylus after the Pokémon. Aerodactyl’s Pokédex descriptions state that it was resurrected “using DNA taken from amber,” an homage to the then-recently released Jurassic Park. Some of the entries actually say “it was regenerated from a dinosaur’s genetic matter that was found in amber,” which makes no sense–which dinosaur?–but this could be interpreted as a further nod to Jurassic Park’s use of frog DNA to patch up their spotty dinosaur genome. One interesting thing about Aerodactyl is that it’s the only Fossil Pokémon with a Mega Evolution, and the game treats this in a unique way. According to the Pokédex, “some scholars claim that [Mega Evolution] is Aerodactyl’s true appearance,” and “apparently even modern technology is incapable of producing a perfectly restored specimen.” This implies that the appearances of resurrected Fossil Pokémon are more like paleoart guesses, and only with the magic of Mega Evolution can one see what they truly looked like in the past. Maybe one day they’ll make a Fossil Pokémon with multiple formes representing different interpretations of the remains! For example, a “raptor” dinosaurian Pokémon that comes in both scaly and feathery formes.

Overall, I think Gen 1’s emphasis on really ancient and less charismatic fossil animals is pretty admirable. Rather than going straight for a Tyrannosaurus Pokémon (more on that one later), they explored the evolutionary relationships and adaptations of ammonites and horseshoe crabs.

Gen 3

Gen 3 sticks with the “obscure prehistoric beast” theme, with the crinoid-like Lileep and Cradily, and the anomalocarid-like Anorith and Armaldo. Similarly to Kabuto, the Little Cup members of the Gen 3 families are essentially just cartoon versions of the real animal. Crinoids are a living group of animals related to starfish, which come in very creepy free-swimming forms known as feather stars, and stalked, sessile forms like Lileep, known as sea lilies. They’ve been around since the Ordovician Period around 467 million years ago, and are still diverse and abundant today, so I’m not really sure why Nintendo chose to claim that Lileep “became extinct approximately 100 million years ago”. Maybe 100 million just seems like a long time?

Anomalocarids, the most famous member being Anomalocaris, were the world’s first apex predators, killing smaller, soft-bodied animals with their claws and sucking them into their little round mouths.

In contrast to Omanyte, the Pokédex says that “when restored Anorith are released into the ocean, they don’t thrive, because the water composition has changed since their era.” I think that’s a neat little detail. The Dex also claims that Anorith also lived 100 million years ago, which is way off from the real Anomalocaris’s range of 513 to 505 million years ago. Again, perhaps 100 million just seemed sufficiently ancient, or maybe Nintendo wants all their Fossil Pokémon to have coexisted in the past. Is this all a setup for a game in which you can go back in time 100 million years and see new formes of all the ancient Pokémon?

When Lileep evolves into Cradily, it goes from being a normal crinoid to being some kind of strange monster. To me, Cradily looks like a sauropod doing the splits, and its head looks like a jingle bell. It’s unclear whether it’s a vertebrate or an invert, and where its mouth is. The Pokédex says it uses its stubby limbs to drag itself around outside the water. It’s not a bad thing to have Pokémon designs that purely imaginary, but it’s a little surprising that literally just a crinoid evolves into something so weird!

When Anorith evolves into Armaldo, it undergoes a similar process of “cool-ification” as Kabuto does when it evolves into Kabutops. The Pokédex for both state that the evolved form is beginning to become adapted for life on land, in order to justify the presence of arms and legs. Neither horseshoe crabs nor anomalocarids have terrestrial descendants, so this is just a case of using science-sounding concepts to rationalize a fantasy creature designed in advance.

Gen 4

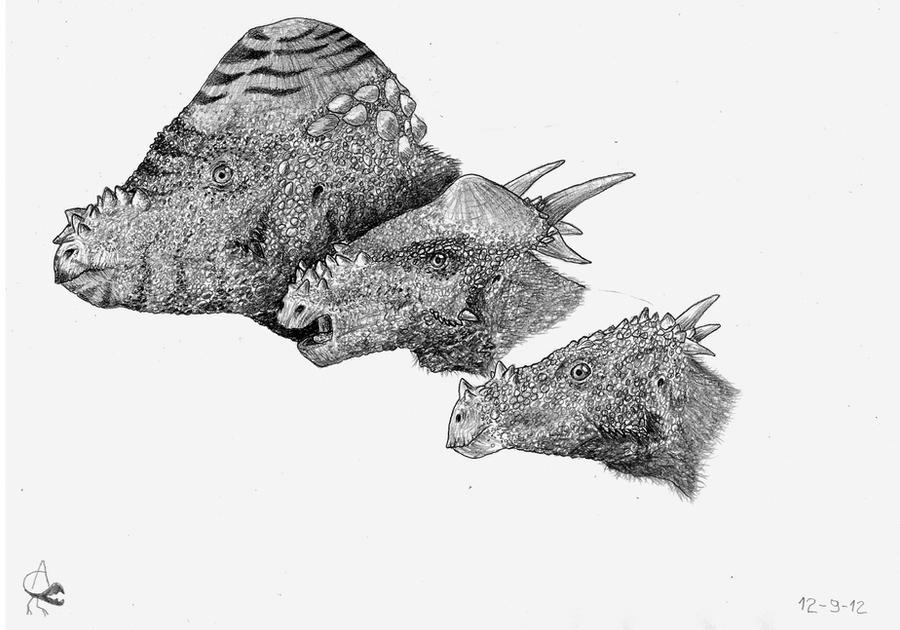

In Gen 4, Nintendo finally gave in to the urge to make Fossil Pokémon based on dinosaurs. Cranidos and Rampardos are clearly pachycephalosaurs, and Shieldon and Bastiodon are clearly ceratopsians. The Pokédex states that all four of these Pokémon lived 100 million years ago, which in this case is a bit too ancient; pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians lived in the Late Cretaceous, around 83 to 66 million years ago.

Cranidos is a small, cute pachycephalosaur with a large domed skull. This is already a missed opportunity–real juvenile pachycephalosaurs had flat heads with lots of spiky horns, and developed the domes when they reached sexual maturity.

The Pokédex states that Cranidos is an herbivore that headbutts trees in order to get at their berries. Rampardos’s entries state that its brain is even smaller relatively than Cranidos’s, which is already said to be unintelligent, and that “some theories suggest that its stupidity led to its extinction.” This is again an example of the “evolved oneself into a corner” misconception. Interestingly, Rampardos is said to be a carnivore, which could be a reference to the fact that pachycephalosaurs are thought to have been omnivorous. So overall, a mixed bag with these Pokémon’s entries.

Shieldon is a plain-frilled little ceratopsian said to eat grass, berries, and roots. Strangely, while one of its Pokédex entries states that it lived 100 million years ago, all the others claim that its fossils were extracted from “a layer of clay that was older than anyone knows.” One also states that “nothing but its face has ever been discovered,” a reference to preservation bias! Nice. Bastiodon is said to have formed “a wall with their shield-like faces to protect their young,” which is something ceratopsians have often been hypothesized to have done (although there’s no direct evidence of it), and which elephants in fact do. Another entry says, “The bones of its face are huge and hard, so they were mistaken for its spine until this Pokémon was successfully restored,” which is not a reference to any specific incident that I’m aware of, but generally refers to paleontologists’ difficulties in reconstructing a skeleton when the bones are discovered disarticulated. I wonder why Shieldon and Bastiodon’s entries are so much more scientific than Cranidos and Rampardos’s! Maybe different writers were responsible for each, some of whom were more motivated to do research than others.

Gen 5

Moving away from the non-avian dinosaurs again, Gen 5 gives us the sea turtles Tirtouga and Carracosta, and the Archaeopteryx-like Archen and Archeops.

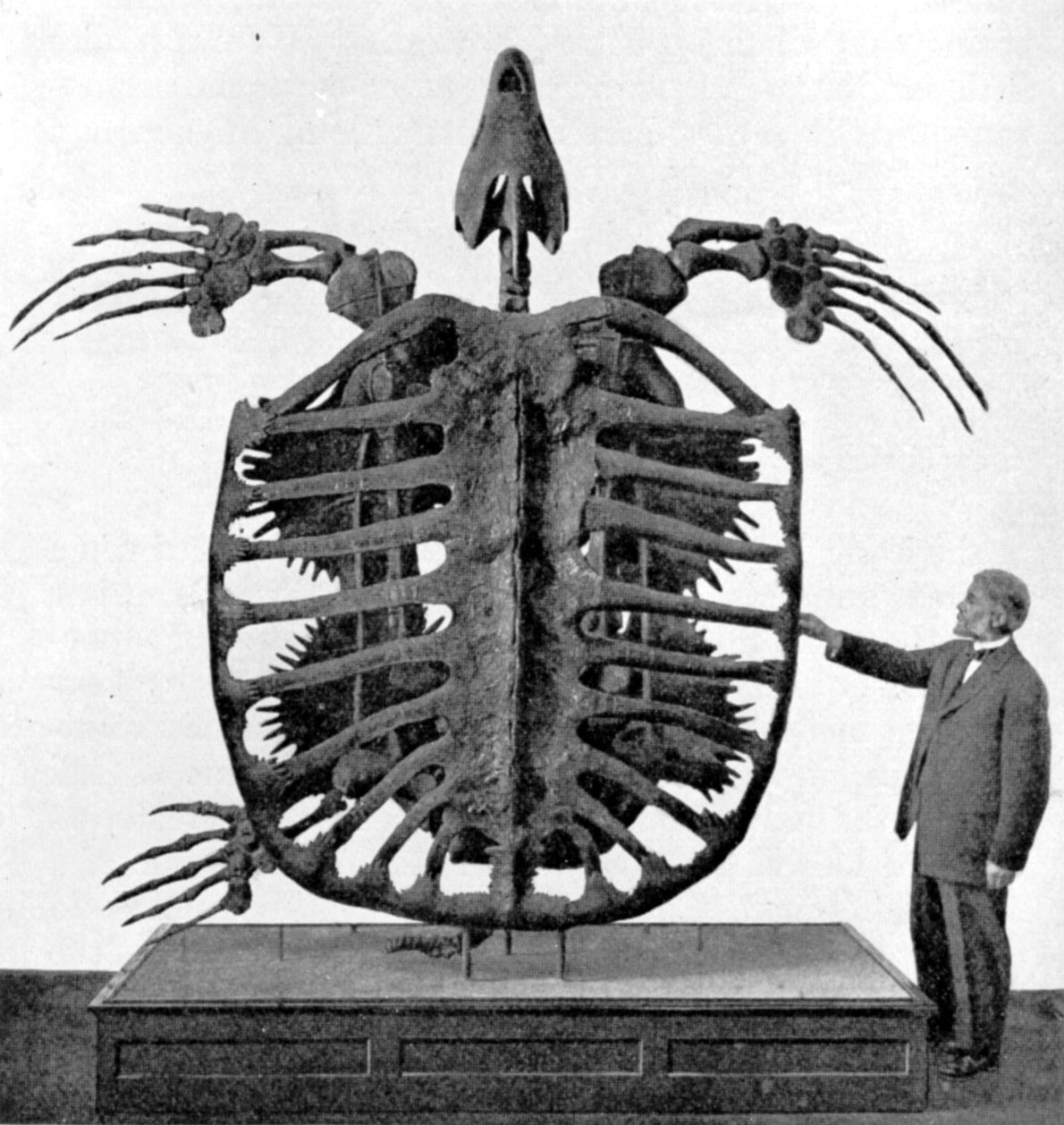

Tirtouga and Carracosta’s designs are strongly reminiscent of the skeleton of the giant extinct sea turtle Archelon:

They both have indentations on their backs that resemble the gaps between the bony struts, and Carracosta has four shield structures on its front that resemble the four pieces of Archelon’s plastron (underside). Carracosta is said to be a durophage, eating the shells and bones of its prey in order to get enough minerals to grow and maintain its own shell, which is identical to what we believe about Archelon’s lifestyle. Tirtouga and Carracosta are again from 100 million years ago–I guess from now on just assume 100 million years unless otherwise specified–which is a bit older than Archelon, which lived 80-74 million years ago, but not too far off.

Archen and Archeops are clearly Pokémon versions of the early bird Archaeopteryx. Archen is incapable of powered flight but is able to glide down from trees, while Archeops can fly but must “use a running start,” representing both the “ground-up” and “trees-down” hypotheses of how flight began. They are both said to be omnivorous, intelligent, and social, which agrees with what we believe about Archaeopteryx. According to the Pokédex, “Once thought to be the ancestor of all bird Pokémon, some of the latest research suggests that may not be the case.” This may be a reference to the recent discovery of older avialans such as the anchiornithids, which displaced Archaeopteryx as the oldest known birds. The Pokédex also states that “this ancient Pokémon’s plumage is delicate, so if anyone other than an experienced professional tries to restore it, they will fail,” a nod to the difficulty of preparing fossils.

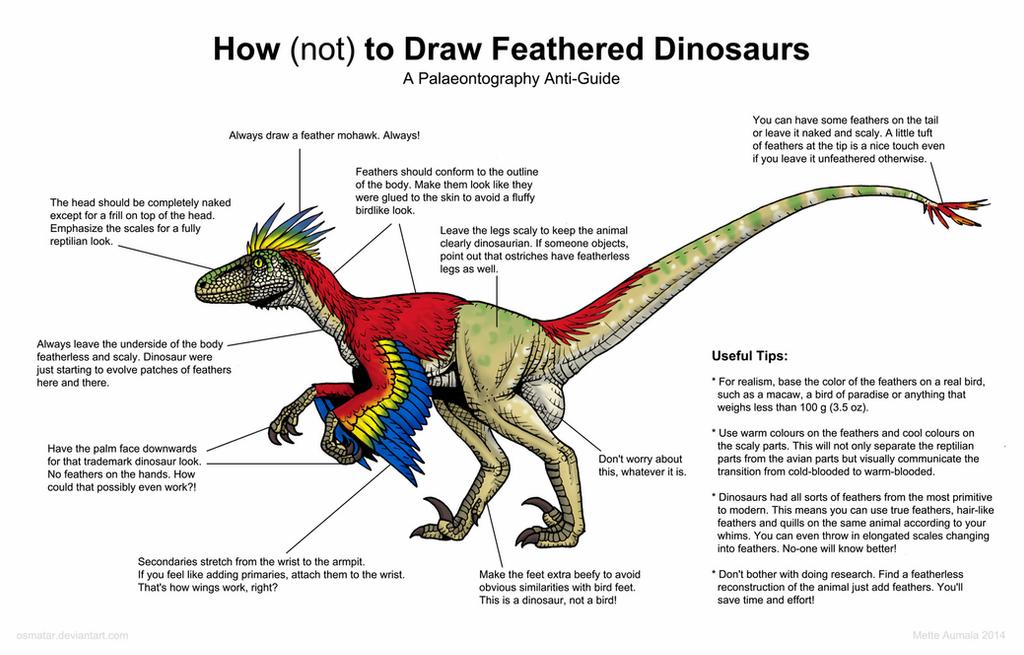

While Archen’s and Archeops’s Pokédex entries are pretty scientific, their appearance is not. Archeops has its primary feathers tacked onto non-wing-shaped arms (and extending all the way up to the armpits). Its foot feathers are supposed to be a reference to four-winged dinosaurs like Anchiornis and Microraptor, but Archeops just keeps its feet tucked up awkwardly in battle instead of using its legs to help it fly. Its contrasty coloration and naked neck, head, and tail emphasize distinct parts as being “reptilian” versus “avian” instead of being one coherent animal. In fact, it eerily resembles the sarcastic infographic about “how not to draw dinosaurs” I used in my other post, except with the base skin and feather colors swapped.

As an interesting side note, Archeops is one of the few Pokémon whose name is made entirely of real word roots, and thus could be a real scientific name. “Arche” is a valid spelling of “archae” and means “ancient,” while “ops” means “face”. Maybe someday an ascended fan will name a real avialan after this Pokémon!

Gen 6

It took Nintendo six generations to finally release a Pokémon based on Tyrannosaurus! And I think no one was disappointed by the result. A dragon-typed, bright red tyrannosaur with the right number of fingers and toes and a cape of feathers–what more could one want?

Funnily enough, Pokémon X and Y came out in 2013, when the 2012 discovery of the super-feathery tyrannosaur Yutyrannus had paleoartists in a T. rex feathering frenzy. Nintendo went for a more subtle look and happened to be proved right in 2017 when a paper by Phil Bell et al describing Tyrannosaurus skin impressions showed that the feathered region, if any, would be limited to the shoulders.

Here’s an example where having two distinct forms representing juvenile and adult makes scientific sense as well. Tyrannosaurus juveniles filled the niche of mid-sized cursorial predator, while the adults lived a different lifestyle as bone-crushing apex predators. This is called niche assimilation, and may explain the scarcity of other mid-sized carnivores in Late Cretaceous ecosystems. Fittingly, while Tyrantrum’s Pokédex entries call it “invincible” and “the king of the ancient world,” Tyrunt’s do not.

Gen 6 also gave us the Pokémon that inspired the page image, Amaura and Aurorus, which are based on the dicraeosaurid sauropod Amargasaurus. This dinosaur is famous for its two rows of backward-pointing spines along its neck, and in the past scientists and paleoartists have hypothesized that they supported a skin sail. However, closer inspection of the spines reveals osteological correlates (bone textures) indicating that they would have been covered with a sheath of horn rather than a sail.

Amaura’s Pokédex entries are full of interesting tidbits. They state that Amaura lived “in a cold land where there were no violent predators like Tyrantrum,” and that “it’s not expected to live long because of the heat of the current environment.” The former statement is a reference to the fact that Amargasaurus lived in South America while tyrannosaurs inhabited the Northern Hemisphere, and that in the Early Cretaceous, South America was connected to Antarctica and Australia and all three continents had portions within the Antarctic Circle. The second statement, while interesting in itself since it provides details about the practicalities of resurrecting Fossil Pokémon, is possibly a reference to the moral question of whether or not it’s acceptable to resurrect woolly mammoths and other Pleistocene megafauna, since the environments they evolved to live in don’t exist anymore. I also like the fact that Amaura’s sails don’t extend all the way down its neck. It seems like a believable ontogenetic progression, since the sails would be a sexual display structure. I also really like the fact that Aurorus has the correct number of toes: three visible claws in back and just a thumbclaw in front. That’s something media representations almost always get wrong. Nintendo really did their homework on this one!

Apparently Amaura whinnies, while Aurorus howls. I suppose you could interpret their cries that way?

Gen 8

Finally, we have the strange hybrid Fossil Pokémon, Arctovish, Arctozolt, Dracovish, and Dracozolt. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the new gen, these are created by a new game mechanism: by combining one of two “front half” fossils with one of two “back halves”. The front halves are a “Fossilized Bird” (something resembling a dromaeosaur, or “raptor” dinosaur) and “Fossilized Fish” (something resembling Dunkleosteus, a plate-armored Devonian fish), and the back halves are a “Fossilized Drake” (something resembling a stegosaur) and “Fossilized Dino” (something resembling a mosasaur or metriorhynchid, neither of which are dinosaurs). While the results are odd and fanciful, the idea behind them is the real paleontological concept of composite specimens. When a full skeleton isn’t available, what do you base your guesses on when filling in the gaps? In the olden days, when ancient creatures weren’t yet well understood and not much fossil material was available, debacles like the “head-on-the-wrong-end Elasmosaurus” and “Camarasaurus head, Apatosaurus body” were common. Dracovish and Arctovish are direct references to the former incident, with Dracovish’s head on the opposite end of the body than Dracozolt, and Arctovish’s head on perpendicular to Dracovish’s (yes, that’s Arctovish’s mouth on the top).

Even their Pokédex entries are extremely tongue-in-cheek, with each describing an “evolved itself into a corner” justification for why the improbable animal went extinct. Dracozolt “went extinct…after it depleted all its plant-based food sources”; Arctozolt “went extinct because it moved so slowly”; Dracovish went extinct due to “overhunting of its own prey”; and Arctovish went extinct due to “breathing difficulties”. Honestly, I love how self-aware these Fossil Pokémon are, but I worry a little bit that the parody will escape younger or less paleo-savvy players.

It seems like when the hybrid fossils came out, a lot of fans hated these designs, but over time they’ve grown in popularity. I hope Nintendo wasn’t scared off by the initial backlash and continues to try creative new things with its future Fossil Pokémon!

Image Credits

Diplocaulus 1 Diplocaulus 2 Dragonite Bulbasaurus Coelacanth Foreyia Plectronoceras Euproops Anomalocaris Wiwaxia Pachycephalosaurus Archelon How Not To Draw Dinosaurs Tyrannosaurus