Now for something a bit more traditional for this blog: a new Paleo Biome Profile! This week I’ll be taking a look at the early Eocene German fossil location known as the Messel Pit.

The Eocene is the second epoch of the Paleogene period, which is the first period of the Cenozoic era. The Messel Pit contains fossils 47 million years old (19 million years after the K-Pg mass extinction that killed the non-avian dinosaurs) in extreme detail, often preserving soft tissue, gut contents, and even fur and feathers. While the Paleocene epoch was mostly a time of ecological recovery, the Eocene was a time of great diversification among mammals and birds, with many of the earliest members of modern groups represented at Messel. However, there were also some older lineages represented, creating an interesting mix of familiar and unfamiliar animals.

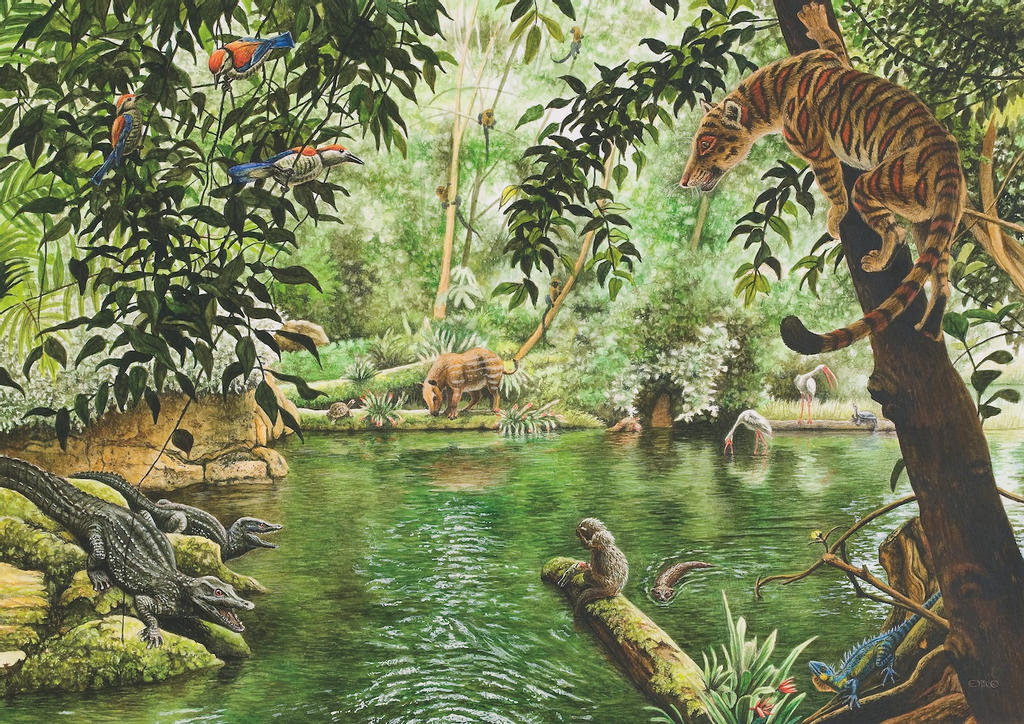

The ecosystem at Messel was a hot, humid subtropical rainforest, very different from the temperate climate of Germany today. This is due to two factors: the continent was 10 degrees further south than it is now, and in the early Eocene, the world was still experiencing the climate event known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), with global average temperatures 5-8 degrees Celsius higher than today. This was a result of multiple factors as well (Central America was still connected to Antarctica and not to North America, resulting in different ocean mixing dynamics; a big volcanic island formed in the north Atlantic that later broke up and became part of Iceland and the British Isles; India had not yet crashed into Asia) but I won’t go into too much detail–suffice it to say that Messel was hot.

The pit itself was a very deep, volcanically active lake, which created great conditions for exquisite fossilization. Periodic release of toxic gases would kill many animals at once, which would sink into the lake intact, and since the lake was so deep, the bottom had such a low oxygen level that the carcasses would not decompose. Often, the exceptional preservation provides cool details about an animal’s lifestyle or appearance. Oh how lucky we are for Lagerstätten!

The plants at Messel would have been recognizably modern, but confusingly located: some of the plant families are now found in South America, such as panama hats and cashews, while others are now found in Southeast Asia and Oceania, such as nutmegs, trees of heaven, and incense trees. Others, such as walnuts and grapes, are still found in Europe. Europe at the time acted as sort of an ecological crossroads between Asia and the Americas, a situation we’ll see repeated with the Messel animals.

There’s an interesting pattern I’ve noticed about the mammals at Messel: ancient groups like the cimolestans (a group more derived than marsupials but more basal than placental mammals), creodonts (relatives of cats and dogs), and mesonychids (carnivorous relatives of hippos) played more specialized roles in the ecosystem, while modern groups like odd- and even-toed ungulates, hedgehogs, rodents, and primates all still shared superficial similarities to the ancestral mammal body plan (read: they all looked kind of like rats). Perhaps this says something about the expected lifespan of a lineage?

Life in the Water

Being a lake, Messel hosted a variety of aquatic or semi-aquatic life, some familiar and some less so. A majority of the fossils at Messel are recognizably modern freshwater fish, such as gar, perch, and eel. Also among the representatives of modern families there was the large crocodile Asiatosuchus and the small alligator Diplocynodon.

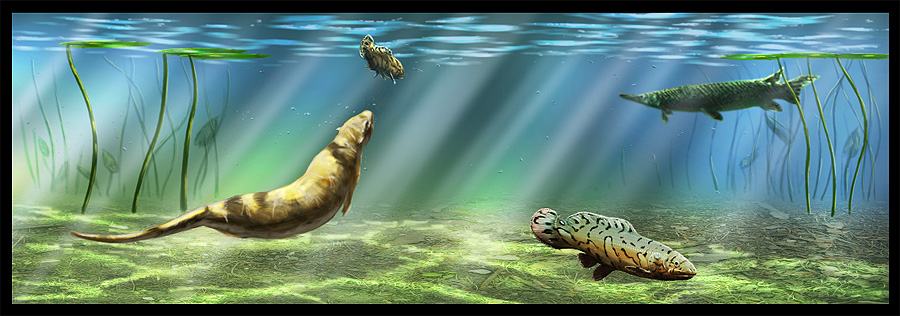

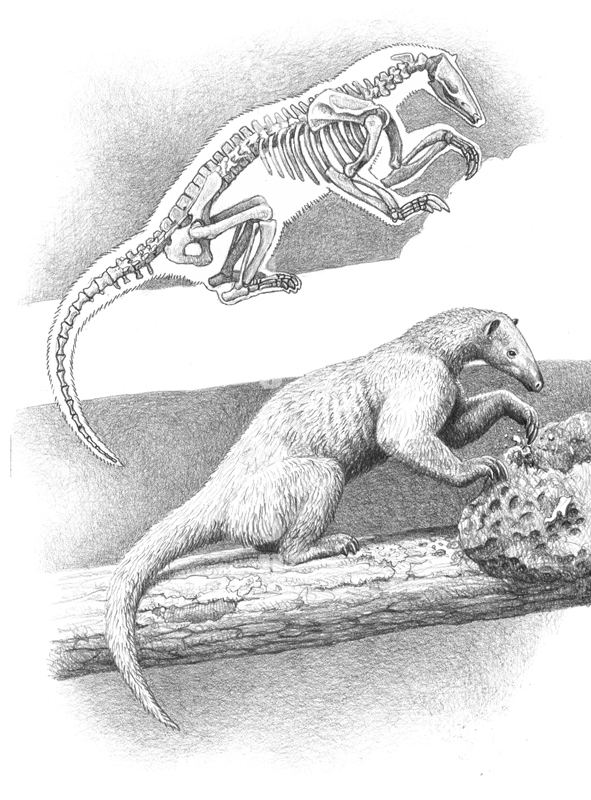

Another important aquatic animal was the otter-like cimolestan Buxolestes, which had a long muscular tail and wide feet for swimming and large molars, possibly for crushing shellfish or snails. Gut contents of fish remains as well as fruit and seeds show that it was a generalist capable of foraging on land.

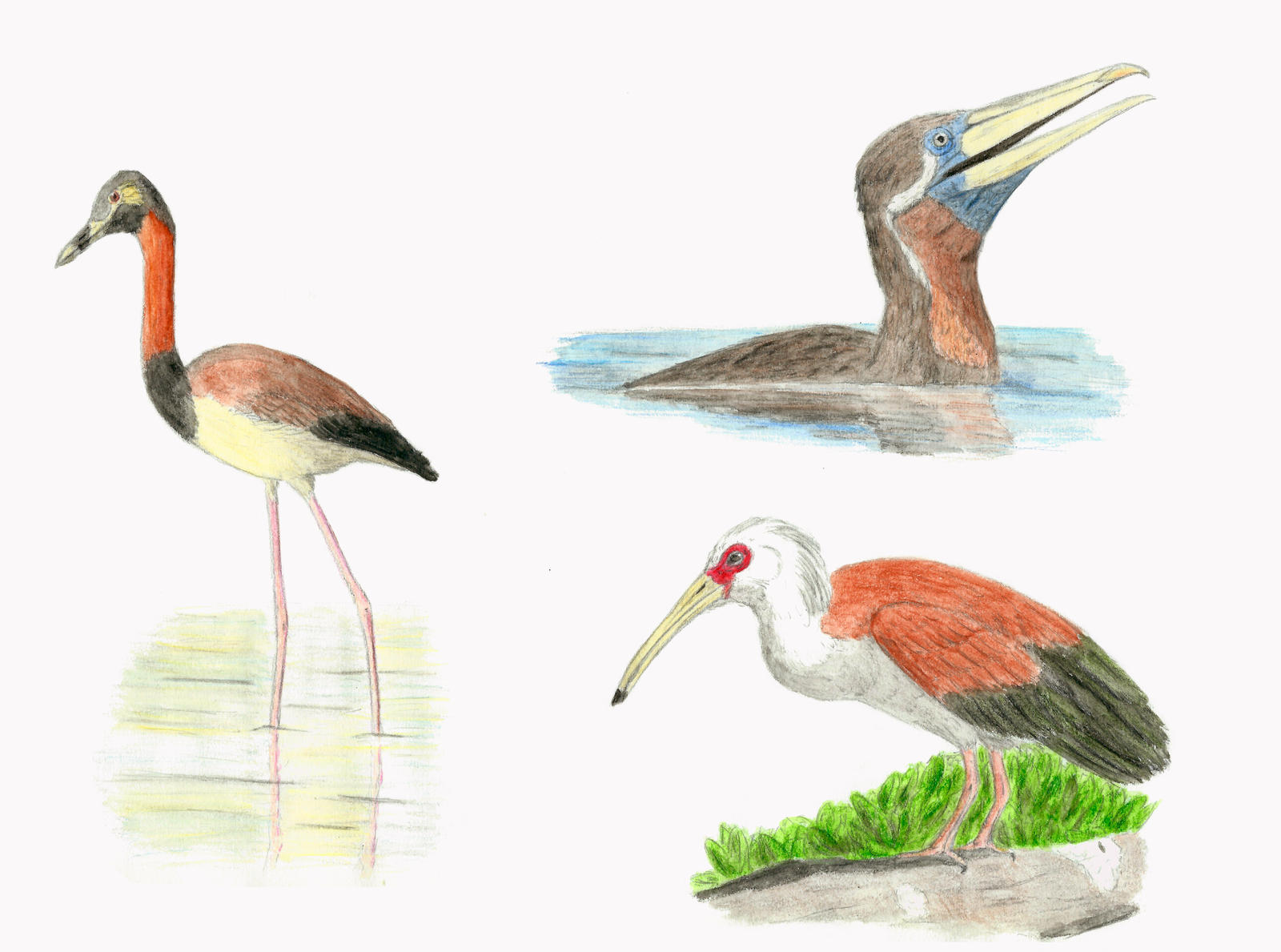

Messel was also home to a variety of waterbirds from many modern families, including early relatives of flamingos, boobies, ibis, kingfishers, and rails.

The early kingfisher relative Eocoracias is particularly notable for a melanosome (coloration) study that concluded it either had non-iridescent structural color, or was gray. Due to the family it’s part of, non-iridescent structural color is much more probable, but we don’t know what color; the official art from the study depicts a dark blue. Structural color is when the physical micro-structure of a surface interacts with light in such a way to produce a color, which is why a hummingbird’s red throat is only red from the front (the micro-structure makes it so that the colored light is reflected directionally), and why soaking a blue butterfly wing in alcohol turns it temporarily gray (the alcohol makes the micro-structure lay flat and therefore stop working).

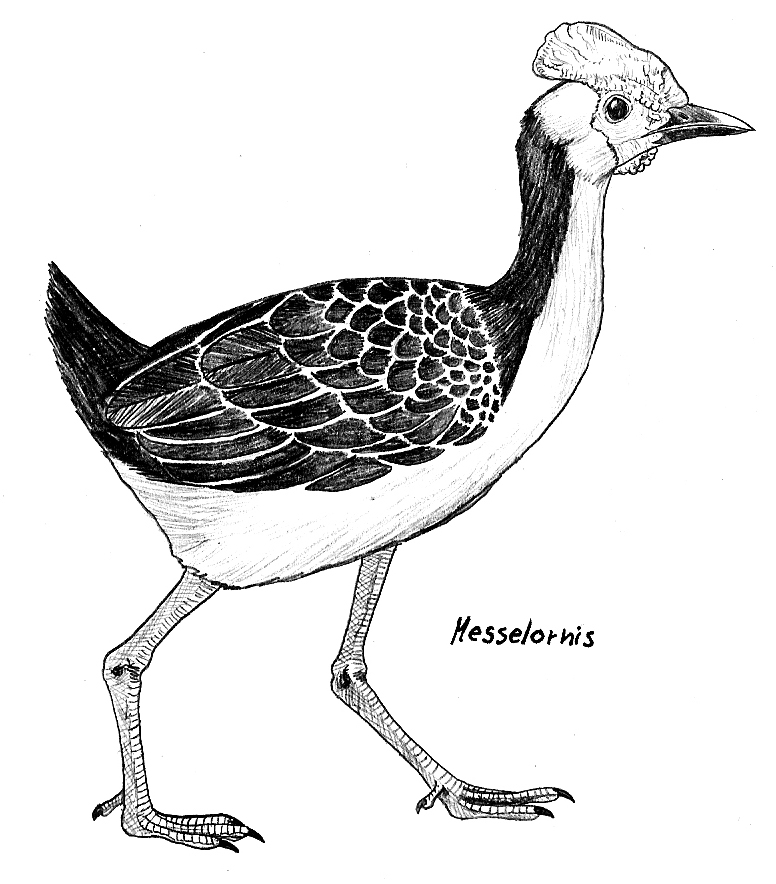

The early rail relative Messelornis is also notable just for its numbers: two out of every three bird fossils recovered at Messel are Messelornis.

The Messel Pit has the honor of being the site of the only known fossils of animals caught in the act of having sex. And not just one fossil–nine male-female pairs of the small, aquatic pig-nosed turtle Allaeochelys have been found like this. These turtles had scaleless skin that allowed them to absorb oxygen from the water, but it also made them particularly vulnerable to Messel’s dangerous volcanic gases.

Life in the Trees

As I stated in my previous Paleo Biome Profile, it’s not common to have a good fossil record of arboreal (tree-dwelling) animals. But Messel provides just that! The canopy above Messel was home to a variety of early primates, early bats, early rodents, more cimolestans doing various specialized things, and representatives from nearly every modern land-bird family.

There are three genera of primates known from Messel, all strepsirrhines (wet-nosed relatives of lemurs): Darwinius, Europolemur, and Godinotia. The latter two are known from spotty remains, while Darwinius’s exquisitely preserved holotype received an inordinate amount of media hype in 2009, lauded as a “holy grail” and “a revolutionary scientific find that will change everything”. The fossil (named “Ida”) had a troubled, partially faked past and sold for $1 million. While it is a very nice fossil of a very early primate, the media attention was almost certainly out of proportion. Since they are all relatives of lemurs, these primates aren’t direct ancestors of humans, so calling them “missing links” is misleading (even setting aside the inherent problematic nature of that term). However, the hype resulted in a children’s book with lots of beautiful paleoart, so it’s not all bad.

(We’ll take a closer look at Gastornis later. This art, along with the first one after the page image, are from the book “Ida,” illustrated by Esther van Hulsen.)

There are also three genera of bats known from Messel; in fact, bats make up the majority of mammal fossils at the site, which is super unusual since the delicate nature of bat bones means they are less likely to fossilize. The three bats are Palaeochiropteryx, a small, maneuverable bat that hunted soft, slow insects in the dark understory; Hassianycteris, a large, fast-flying bat that hunted fast, hard-shelled insects in the open space above the canopy; and Archaeonycteris, a medium-sized bat that would have inhabited the overstory. We know their respective diets based on fossilized gut contents, and can extrapolate their lifestyles based on that as well as the shape and size of their wings. A great example of niche partitioning! The earliest bats appeared rather suddenly around 52 million years ago, and Messel’s bats, 5 million years later, would have looked and acted essentially modern, lacking the primitive wing claws that earlier bats had and showing early adaptations for echolocation, though not as advanced as those of modern bats. Melanosome studies on Hassianycteris and Palaeochiropteryx have shown that they were (surprise, surprise) reddish-brown when alive. Still, it’s cool that we know for sure!

I won’t go into too much detail about the Messel land-birds, since most of them are early representatives of modern families and look recognizably modern, but I’ll give a couple of notables a shout-out. Masillaraptor was an early falcon with very long legs, possibly a snake specialist–the falcon family’s answer to secretarybirds. (Falcons, while very similar in appearance to hawks, are actually much more closely related to songbirds.) This is what’s depicted in the page image at the top, preying on Rageryx the dwarf boa. Messelastur was a parrot relative that filled the role of a hawk or falcon.

Messel was also home to some members of more ancient lineages that converged on familiar lifestyles.

Life on the Ground

The terrestrial fauna at Messel included very early relatives of horses, tapirs, rhinos, artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates), and pangolins, while also containing unfamiliar animals such as giant axe-beaked birds, terrestrial fast-running crocodylians, and mammals convergent with modern body plans but which defy phylogenetic classification.

There are three genera (three seems to be the magic number) of early pangolins found at Messel: Eomanis, a small, scaled pangolin that looked a lot like modern pangolins, though its scales didn’t cover as much of its body; Euromanis, a small, completely scaleless pangolin; and Eurotamandua, whose name means “European anteater” since it is so convergent with anteaters that it was long mistaken for one. While pangolins and anteaters share a lot of traits due to convergent evolution, anteaters hail from a very distant mammal family, the xenarthrans, which aren’t found in this time and place.

The early horse Propalaeotherium is one of the most iconic mammals from Messel, although it always seems to be depicted as being preyed upon by larger animals. It was tiny, the size of a small dog, and still had multiple fingers and toes on each foot with little hooflets on each finger (modern horses have one toe per foot, and the hoof is a single fingernail). It was a browser, rather than a grazer, selectively eating berries and soft leaves, in contrast to its modern relatives, which digest huge volumes of poor-quality food. Eurohippus was a closely related little horse that was even smaller and slenderer than Propalaeotherium, at only 5 to 7 kilograms (the size of a toy dog). Both are known from dozens of specimens.

Another ancestral odd-toed ungulate at Messel was the rhino ancestor Hyrachyus.

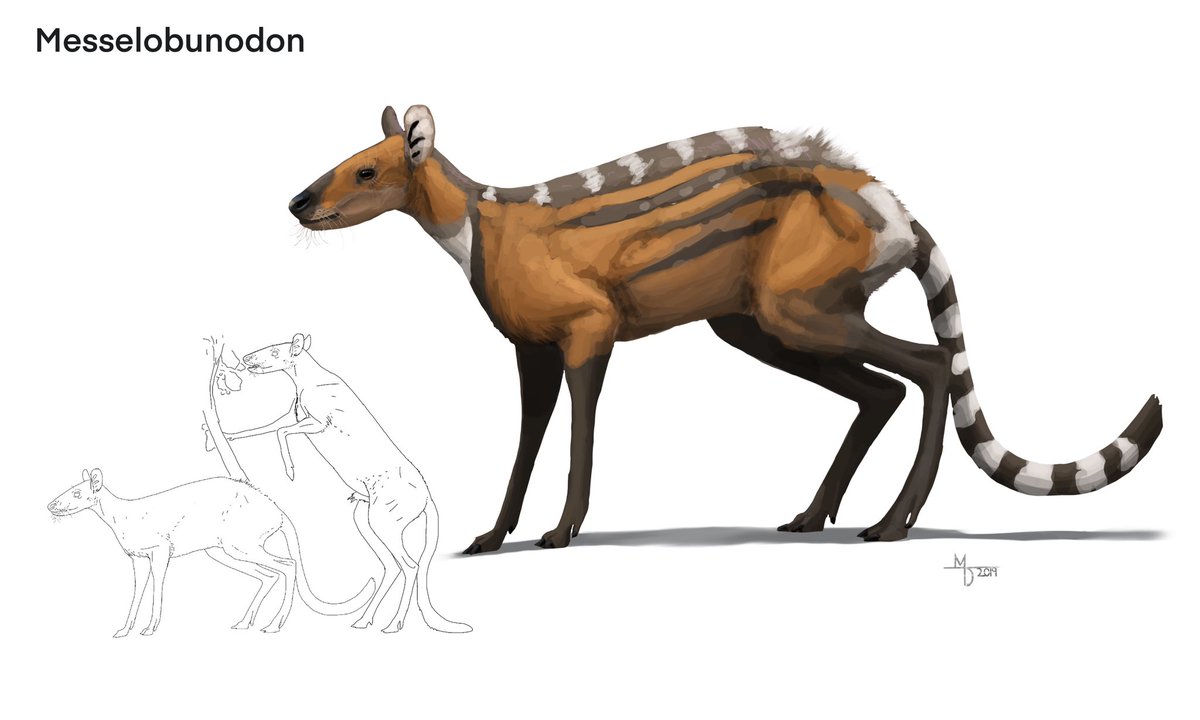

And here we have the ancient even-toed ungulate (an ancestral relative of cloven-hoofed animals like cows and pigs, hippos, and whales) Messelobunodon.

Okay, let’s address the elephant in the room: the giant duck relative, Gastornis. This two-meter-tall axe-headed bird was actually an herbivore, possibly using its muscular jaws to crack nuts, in contrast to the carnivorous South American phorusrhacids (“terror birds”) that lived around the same time. Superficial similarities between Gastornis and terror birds caused lots of paleoartists to depict Gastornis terrorizing the small mammals of Messel, especially poor Propalaeotherium, but its bone chemistry indicates that it had very little meat in its diet. This hypothesis is corroborated by its footprints, which lack weaponlike claws. A giant preserved feather shows that they had complex plumage, rather than the shaggy, emu-like plumage common in older art.

Speaking of Eoconstrictor, let’s discuss it in more detail. This two-meter-long boa relative was probably a generalist, able to climb trees but also spending considerable time on the ground, and gut contents show that it preyed on large lizards and small crocodylians. It also had heat-sensing organs in its upper lip area, but since it hunted cold-blooded prey, it’s possible that heat sensing arose as an adaptation for better sensing the environment rather than specializing in hunting warm prey. There are also three other, smaller booid snakes known from Messel, two of which (Rieppelophis and Rageryx) were terrestrial and one of which (Messelophis) was arboreal, but none of the smaller snakes had heat-sensing pits. This doesn’t mean they didn’t sense heat though–some modern snakes have a rudimentary, pitless heat-sensing system, though the pits provide more sensitivity, higher resolution, and a better frame rate. Apparently snakes’ brains take the incoming infrared information from their pit organs and overlay it on their vision. They actually see through their lips! Another important ancestral snake from Messel was just discovered at the end of last year: Messelopython, the oldest known python. Since modern pythons’ range doesn’t overlap with that of boas, it was thought that they were too similar to coexist; however, it’s clear that their ancestors could.

With the reclassification of Gastornis as an herbivore, what animal held the apex predator niche at Messel? Surprisingly, none that we know of. However, there were a lot of mid-sized carnivores of various stripes, many of which hailed from ancient, unfamiliar lineages.

Every ancient ecosystem worth its salt has at least one terrestrial crocodyliform!

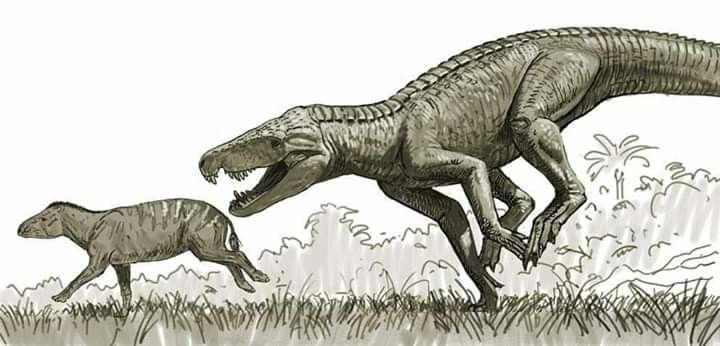

While no mesonychids are known from Messel itself, I wanted to mention them anyway, since they were an important part of early Eocene ecosystems and may have passed through Messel from time to time. This was a group of ungulates (hoofed animals, in this case probably related to hippos) that became carnivorous or omnivorous and would have filled a similar ecological niche to modern carnivorans (cats, dogs, and bears). Why don’t we have carivorous terrestrial ungulates today? Lame.

In addition to miacids and mesonychids, there was a third ancient lineage of carnivores at Messel: the creodonts, represented by the weasel-sized Lesmesodon.

Last but not least, here’s the hopping, prehensile-snouted insectivore of uncertain affinity, Leptictidium.

What’s strange about this is that saltatorial (hopping) locomotion most often evolves in desert climates. I wonder what Leptictidium was doing that made hopping a good idea in a rainforest!

Conclusion

This has been a super quick fly-by of the fauna of the Messel Pit, and by no means a comprehensive list. I didn’t even get around to the insect fossils, which are super impressive. (My vertebrate bias only deepens as I learn more about vertebrates–the overhead required to understand any context behind insect evolution is daunting!) The Eocene is probably my favorite epoch of the Cenozoic, but since I’m mainly a dinosaur girl, I hadn’t done much in-depth research about it until now. We are so lucky to have a source of such abundant and well-preserved fossils from this important transitional period–they’ll keep paleontologists busy for decades because there’s so much information contained in them.

Image credits

Messel ecology Kopidodon Ailuravus Macrocranion Buxolestes Messel waterbirds Eocoracias Messelornis

Darwinius Messelastur Paroodectes Heterohyus

Messel landscape Eurotamandua Propalaeotherium Hyrachyus Messelobunodon Mark Witton’s Gastornis Bergisuchus Dissacus Lesmesodon Leptictidium

References

Eoconstrictor study Messel overview Eocoracias study Earth viewer Messel mammal overview study Bat coloration study Pangolin study Bat niche partitioning study Biomechanical study