Lately I’ve been reading a lot of nature books, and quite a few of them have mentioned natural beauty as it relates to one topic or another. I thought it would be worthwhile to synthesize all these viewpoints together into a comprehensive post that answers a few questions about beauty: What do we find beautiful and why? Do other animals appreciate beauty in a comparable way? What are the evolutionary benefits to being beautiful or producing beautiful things? When did beauty arise in the fossil record, who did it first, and why?

What is beauty?

Obviously, sometimes beauty is in the eye of the beholder, i.e. it’s subjective. However, humans and other animals do show systematic preferences, both inborn and cultural, for certain aesthetics over others. Bowerbirds compete to build the perfect bower and complement it with song and dance, bees and other pollinators are drawn to certain flowers over others, anecdotes exist of bears and chimps watching a particularly stunning sunset, and the list goes on. I’m going to categorize beauty into four main types, roughly in the order that they arose: honest indications of fitness, sexually selected traits, interspecies attraction (e.g., flowers), and unconscious or landscape beauty.

Honest signals of fitness

The oldest form of beauty is simply anything that indicates honestly that an organism is healthy and has the resources at their disposal to successfully create and rear offspring. For humans and many other animals, this would include things like smooth skin, which indicates health, youth, and a strong immune system; large eyes, thick, lustrous hair, and full lips, which indicate youth; and symmetrical features, which indicate a childhood free of disease and hunger. Until recently, fatness was also on this list, since it indicated an abundance of resources, as well as smooth hands, which indicated that the bearer had enough resources to not need to labor. But since industrialization caused fattening food to be the cheapest food, while going to the gym requires abundant time and money, being skinny has become beautiful.

These sorts of simple laws of attraction have been around since sexual reproduction has existed, 1.6 to 2.1 billion years ago. The first organisms to exhibit preferences of this type would have been single-celled eukaryotes, possibly resembling Paramecium.

Sexually selected traits and behaviors

In the game of honest signals of fitness, how does one get ahead of the competition? By exaggerating these signals, or even handicapping oneself to display just how much wealth and power one has to spare. In contrast to honest signals of fitness, these traits and behaviors decrease one’s fitness by wasting time and resources or imposing a burden on the bearer. Think of a peacock’s tail (the sight of which, before Darwin came up with the theory of sexual selection, “made him sick”), a moose’s antlers, or a hadrosaur’s crest.

Usually, sexual selection takes the form of males being the flashy ones and females the choosy ones. This is because a female can only produce a limited number of offspring, so it’s important to ensure quality, while a male can produce as many offspring as he can convince females to mate with him. In other words, a male wants to mate with as many females as possible, while a female wants to make sure she only mates with the best male she can. This dynamic leads to the males of many animal species being extremely flashy, and often engaging in intensive mating rituals to please the ladies. In birds, this can manifest as colorful and unwieldy plumage, complex song, mimicry, and dance, and the building of elaborate structures such as bowers or dancefloors. In humans, this can manifest as conspicuous consumption, playing sports, or writing love songs, to name a few.

Sometimes, in species that operate closer to monogamy or in which females have to compete with each other for resources such as nesting sites or access to males, sexual selection acts in both directions, with the females becoming flashy, sometimes in their own distinctive way. Among eclectus parrots, native to Oceania, the males are bright green with red and blue accents, while the females are bright red with purple and yellow accents. They look so different that people thought they were two different species until someone observed a green one on top of a red one in the wild. The females are bright in order to stake claim to their preferred tree-hole nests, which are rare in their environment, and to attract wandering males, since they do not pair-bond. As bright as they are in the visible spectrum, these birds see each other as even more spectacular than we do, since their plumage has ultraviolet patterning as well.

Similarly, dark-eyed juncos, a small, ubiquitous Northern Hemisphere songbird that you have almost certainly seen before, are usually migratory, and the females don’t sing. Loss of female song is common among migratory birds; it’s hypothesized that the time constraint imposed by migration makes it advantageous to divide the labor of raising a family between the males and females. The male sings to defend the pair’s territory while he’s out gathering food, which allows the female to focus on building the nest and brooding the eggs and young. However, when a group of dark-eyed juncos took up year-round residence at UC San Diego due to the abundance of birdfeeders, the females started singing as well.

How do we detect sexually selected characteristics in the fossil record? The three main things to look for in deciding whether or not an exaggerated trait is a sexual display feature are sexual dimorphism, positive allometry, and changes in growth rate during ontogeny. Sexual dimorphism means that the males and females look different from each other, and can be mild, as in humans, or extreme, as in the pterosaur Darwinopterus, with males possessing crests and females going without.

Positive allometry means that as an animal gets bigger, the trait in question gets proportionally even bigger, such as the huge antlers of the extinct Irish elk. In other words, a larger adult male specimen would be expected to have even larger antlers than you’d get by linearly scaling up a smaller adult male. Ontogeny is the way an organism grows up; changes in growth rate during ontogeny means that a trait may stay small or nonexistent until puberty, at which point it grows rapidly, since it is only then needed for sexual display. Examples of this include the development of peacock tails, deer antlers, fiddler crab claws, pterosaur crests, hadrosaur crests, and ceratopsian horns and frills. While none of these three indicators is exclusive in itself to sexually selected traits (for example, anglerfish are extremely sexually dimorphic, with the males hundreds of times smaller than the females, but this is due to some other reason than sexual display by the females), if all three are present in a fossil species it’s highly likely that the trait in question is for sexual display.

The earliest probable example of a trait like this is the brush fin on the Devonian chimera-relative, Stethacanthus. Again, this is a case where the male and female were originally thought to be different species (the female was named Symmorium) before getting lumped back into one.

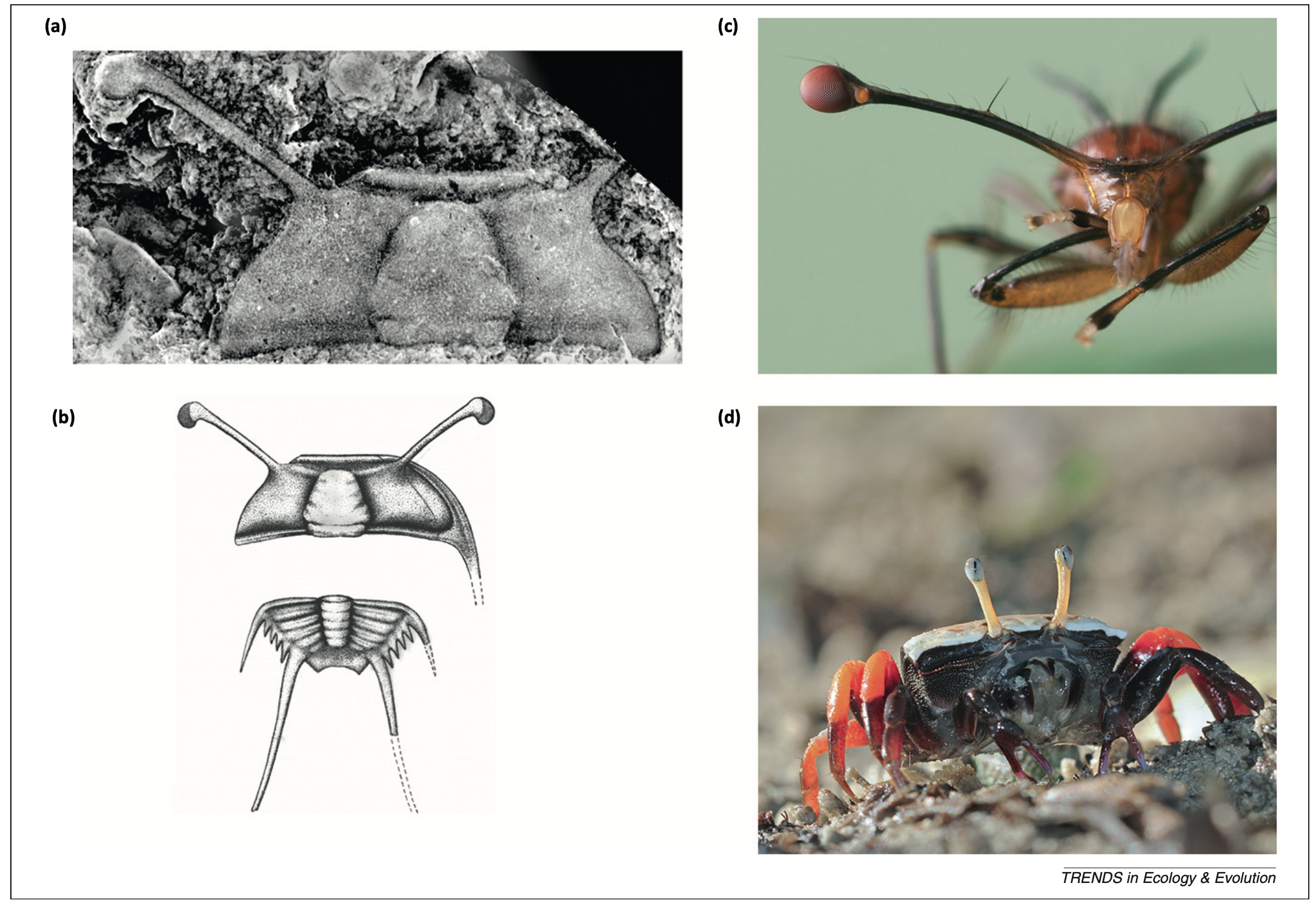

However, as per usual in the fossil record, the actual first instance of a sexual display trait must have come much earlier. One possible example is found in Cambrian trilobites such as Parablackwelderia, which lived 501 to 497 million years ago, and had exaggeratedly long stalk eyes. In the modern day, certain flies and crabs have super long eyestalks, and the flies use theirs for display while the crabs use theirs to peep around while buried in mud. Which was the case for the trilobites? Both?

By the Devonian period (when Stethacanthus lived), trilobites had diversified into forms with highly exaggerated structures that were almost certainly for display, which means that less-exaggerated versions must have arisen earlier.

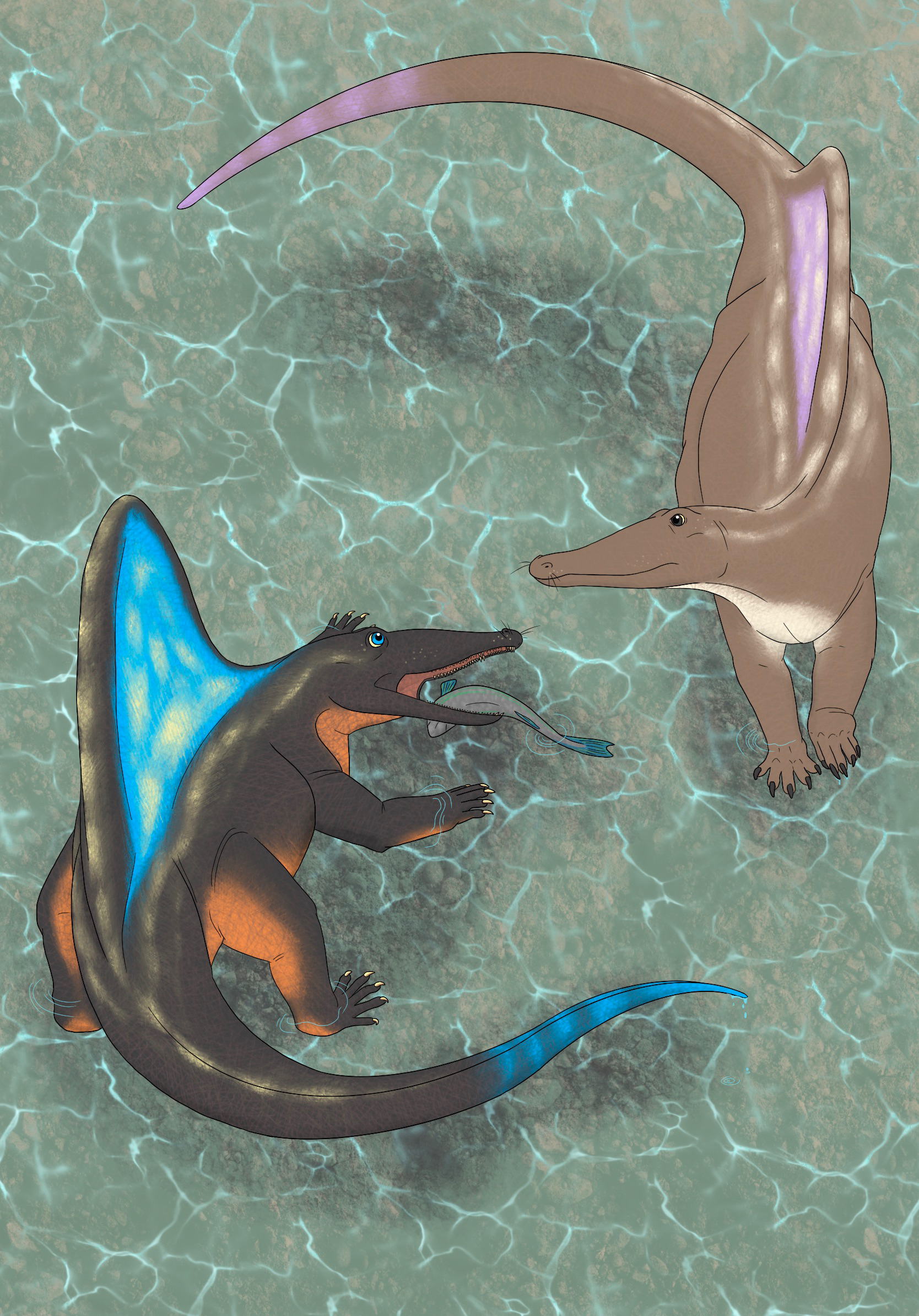

The page image at the top is my depiction of the carnivorous pelycosaur Secodontosaurus, which is a slightly smaller, slender-faced relative of the much more famous Dimetrodon. It lived in the late Early Permian, 285 to 272 million years ago, and though it was cold-blooded, semi-sprawling, and lacking external ears (or even ear holes) like a reptile, it was more closely related to mammals. Here, I’ve given them a few whiskers, since those are useful for sensing regardless of endo- or ectothermy. Many functional hypotheses have been proposed for these creatures’ large spinal sails, such as thermoregulation, hydrodynamics, and fat storage, but even if they did perform one or more of these functions they were so exaggerated that it would be highly unlikely if they weren’t also for display.

Preferences for extravagant antlers or flashy colors in mates in general makes sense due to the handicap principle, but why do animals prefer specific types of song, dance, color, pattern, and structure? Why is buying a rare and expensive diamond ring high-status, while buying a rare and expensive cornflake shaped like Illinois or Pokémon card is not? In many animals, including humans but also including such distantly related animals as flies and guppies, taste depends on the tastes of others. Virgin fruit fly females consistently prefer mating with a male fly that is the same color, either red or green, as the one they’ve seen other females mate with; virgin female zebra finches prefer males with a white leg band, or an artificially attached striped head feather, or whatever, if that’s the type of male they’ve seen other females mate with. Even the handicap principle can be undone by peer pressure: female guppies can learn to prefer drab-colored males over bright ones if they see other females mating with the drab ones. Many songbirds have regional musical styles, and when transplanted to a different region, the local females don’t like the foreign song.

This still doesn’t answer the question, why do we appreciate the beauty of other animals’ sexual displays, given that we are not the intended audience? There is more to beauty than just social conformity and handicapping, and I’ll address it further in the last section of this post.

Interspecific attraction: flowers and fruit

Flowers and fruit, which are produced by the clade of plants known as angiosperms (in a one to one relationship: where there is a flower, there will later be a fruit), get their own category because they invented a distinct reproductive strategy: using other species as vectors for their reproductive cells. Angiosperms coevolved with pollinators and seed dispersers in the Cretaceous period, arising about 120 million years ago but only completing their quest for world domination in the Miocene epoch, around 21 million years ago, with the spread of grasslands. Different strategies exist for enlisting the help of animals in plant reproduction: sweet nectar, advertised by bright colors; fragrances reminiscent of some other animal desire, such as the famous giant Rafflesia that smells like rotting meat; optical illusions like the prostitute orchids of the genus Ophrys that look like a female bee viewed from behind in order to trick male bees into attempting to mate with them; and tasty, fleshy fruit with hard or bitter or otherwise protected seeds meant to be excreted, unharmed, elsewhere by a specific animal partner.

Coevolution is when two or more species influence each other’s evolutionary paths, resulting in highly specialized and complex interactions between partners (or, in other contexts, parasite and host). The evolution of angiosperms and pollinators is the textbook example of this phenomenon: when someone sent Charles Darwin a Star of Bethlehem orchid, a flower with a ridiculously long and thin nectar chamber, he said, “Good Heavens, what insect can suck it?” and wrote that there must be an insect with a foot-long proboscis for whom this flower is built. Twenty years later, the giant hawkmoth was discovered.

You can also use properties of a fruit to predict traits of the intended eater. Small fruits such as berries are for small animals like birds and rodents, while large ones such as avocados and Balanites rely on large dispersers like giant ground sloths and elephants. Brightly colored fruits are for animals with good color vision (and the specific color can predict what spectrum the viewer’s eyes work best in–a species of traveler’s palm native to Madagascar even has seeds that are ultraviolet, for visibility to aye-ayes), while drab, fragrant ones are for animals that forage mainly by smell. When one partner of a coevolutionary relationship goes extinct, the other is often in danger as well. You can read more about it in my older post on evolutionary anachronisms.

But again, why do we find flowers pretty, when we aren’t the target audience? Due to the one-to-one correspondence between flowers and fruit, it would have been advantageous for our ancestors to have been able to keep track of flower locations in order to beat the crowd when the fruit was ripe. Many primates are fruit specialists, and in the wild, chimps and orangutans have been observed waking before dawn and trekking miles in a very determined, premeditated fashion to reach a particular fruit tree before the rest of the forest got up. A parallel situation exists among parrots, which are also social fruigivores, which may explain why they independently evolved higher intelligence.

Still, we seem to value flowers for more than just their fruit-predicting ability. Rituals surrounding them feature in nearly every human culture; many flowers that are culturally important, such as the tulip, don’t produce fruit we can eat; and having no emotional response to flowers is considered a symptom of clinical depression. I’ll discuss the rest of the reason we like flowers so much in the next section.

Unconscious beauty: forests, mountains, and sunsets

There are certain things we find beautiful that are not part of a grand evolutionary strategy, and are incapable of appreciating the fact that we appreciate them. These include the functional parts of plants such as leaves and wood, which would much prefer to be left alone rather than eaten or turned into a coaster; nonliving things like waterfalls, mountains, and stars; and physical phenomena such as auroras, rainbows, and sunsets. As I stated in the introduction, people have observed bears and chimps enjoying sunsets–the latter sometimes even hold hands with a friend or lover while watching. And crows and other birds share our fascination with useless, glittery trinkets. This (along with the fact that evolution is continuous and the parsimonious hypothesis is nearly always that humans aren’t special) suggests that we aren’t alone in perceiving beauty in things that don’t care whether or not they are beautiful.

But what is the evolutionary benefit of having a sense of beauty? Consider a primordial worm living 600 million years ago. It eats bacteria that it scrapes off hard microbial mats using its radula (scratchy tongue), which is hard work. A worm that only eats when it is hungry is more likely to starve than one that enjoys eating. Furthermore, if the worm is capable of distinguishing levels of enjoyment derived from different foods, it can choose what to eat–and the worms that find the highest-calorie food tastiest are the ones whose opinions get passed down. So, a sense of aesthetics is adaptive. As a corollary, an organism that enjoys life more in general is more likely to want to live, and will do more to try to survive. Enjoying the beauty of things may give animals additional motivation that can aid survival and reproduction.

As a last word, please enjoy this video of Koko the gorilla critiquing her own artwork. “It’s not excellent. It’s toilet.” Clearly, this particular piece isn’t up to her aesthetic standards.

References

Naish, Darren. “Sexual Selection in the Fossil Record.” Scientific American Blog Network, Scientific American, 7 Sept. 2012, blogs.scientificamerican.com/tetrapod-zoology/sexual-selection-in-the-fossil-record/.

Knell, Robert J., et al. “Sexual Selection in Prehistoric Animals: Detection and Implications.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 28, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2013, pp. 38–47., doi:10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.015.

Pollan, Michael. The Botany of Desire: a Plant’s Eye View of the World. Random House, 2014.

Safina, Carl. Becoming Wild: How Animal Cultures Raise Families, Create Beauty, and Achieve Peace. Thorndike Pr, 2021.

Safina, Carl. Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel. PROFILE Books LTD, 2020.

Mallon, Jordan C. “Recognizing Sexual Dimorphism in the Fossil Record: Lessons from Nonavian Dinosaurs.” Paleobiology, vol. 43, no. 3, 2017, pp. 495–507., doi:10.1017/pab.2016.51.

Gould, Stephen Jay. “Positive Allometry of Antlers in the ‘Irish Elk’, Megaloceros Giganteus.” Nature, vol. 244, no. 5415, 10 Aug. 1973, pp. 375–376., doi:10.1038/244375a0.

Klein, Joanna. “Plants Can’t Talk. But Some Fruits Say ‘Eat Me’ to Animals.” The New York Times, 9 Oct. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/10/09/science/fruit-color-evolution.html.