I recently went on a trip to Boston to visit friends, and of course had to make a detour to see the Harvard Museum of Natural History, which was the home of the famed paleontologist Alfred Romer (of Romer’s Gap) and houses the world’s only mounted Kronosaurus skeleton. Paleontology is only a small slice of what the museum has to offer, with large anthropology, entomology, and art sections, but in this post I’ll focus on the paleontology and evolution exhibit. How does it measure up?

“Evolution” exhibit

The first room in the paleontology section is on the mechanism of evolution, and an overview of the taxonomy of vertebrates. At first glance, I was excited–they had a cast and model of Tiktaalik, a transitional tetrapod that was discovered in 2006, demonstrating a minimum level of modernity, and an impressive collection of taxidermied song sparrows and snail shells from different climes as an example of intraspecies diversity. I didn’t know song sparrows could vary that much from place to place!

Here’s the “fishapod” Tiktaalik, an important example of what the earliest vertebrates capable of moving on land would have looked like. While most fossils are discovered by happenstance when a bone is spotted weathering out of the ground, or by digging in known fossil beds, Tiktaalik is unique for being sought out. The discoverers, Neil Shubin et al (including Harvard professor Farish Jenkins Jr, who may be the reason for this exhibit), went to one of the only places in the world–Arctic Canada–where the geology might allow for such an animal from the expected time period to be preserved, and dug and dug for years until they found it.

I especially like the fact that they highlight the difference in posture between using a limb as a fin versus as a leg. They don’t really get into what bone or muscle features Tiktaalik had that previous lobe-finned fish didn’t, but it’s still a cool detail to show.

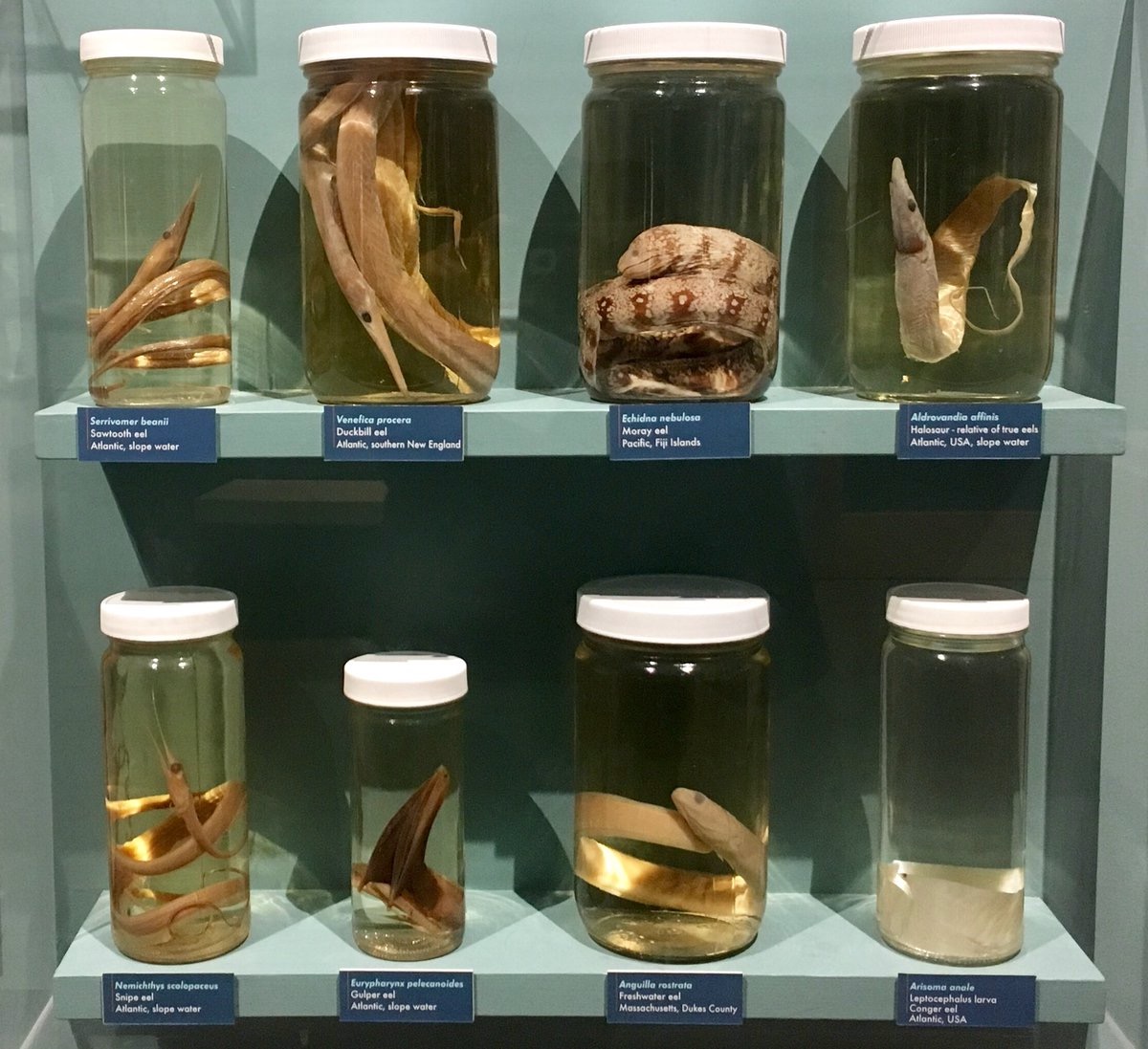

On the other side of the room, there are formaldehyde-preserved specimens in jars of different types of salamanders, bats, and eels, showing both divergent and convergent evolution. Salamanders from different families evolve similar characteristics depending on whether they are arboreal (tree-climbing), terrestrial, or fossorial (burrowing), and eels with different lifestyles diverge into a variety of shapes and sizes, from the huge-mouthed gulper eel, to the pointy-snouted snipe eel, to the pitbull-faced moray, to the tiny-headed longtrunk conger eel (with a typo–it should say Ariosoma, not Arisoma).

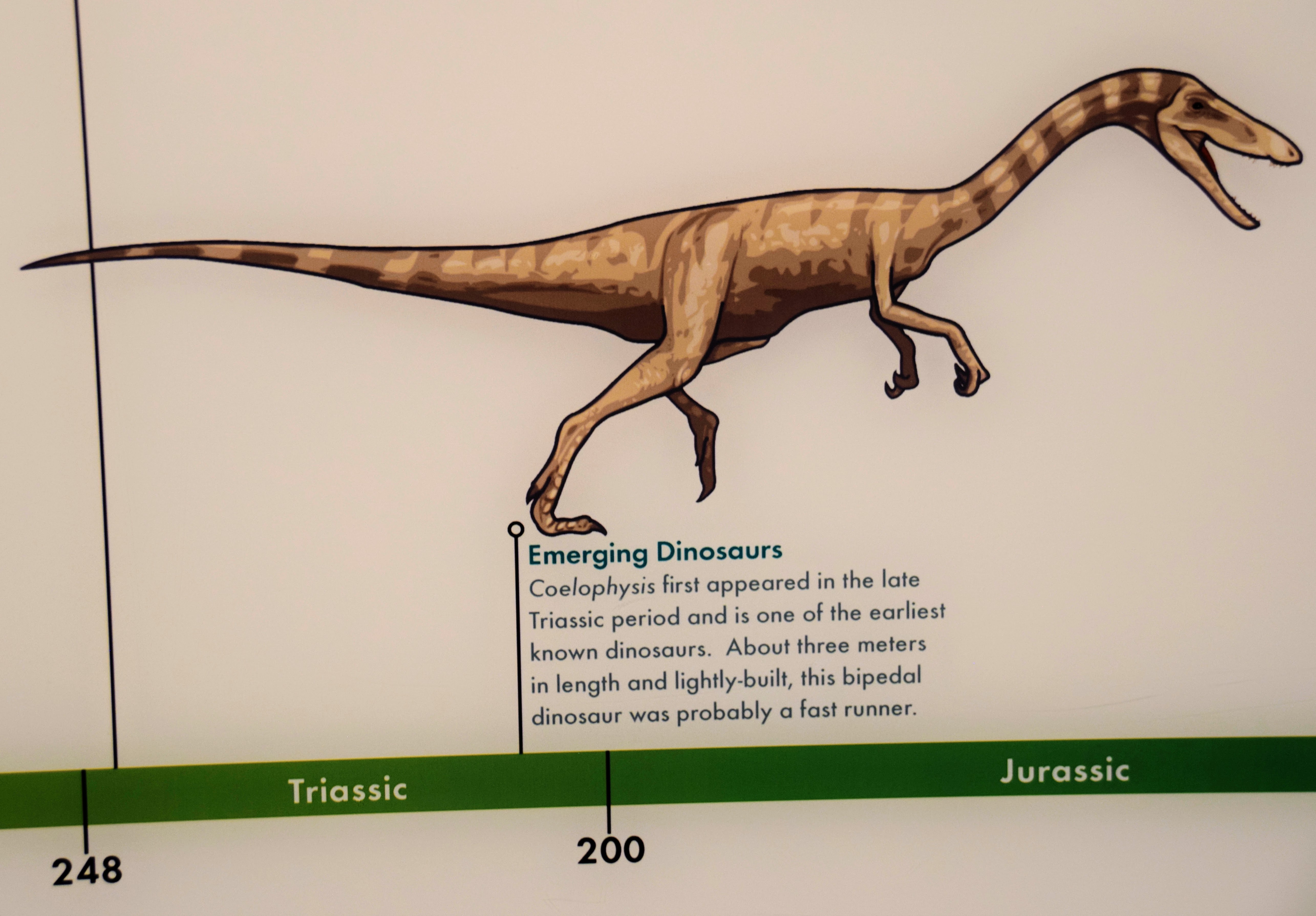

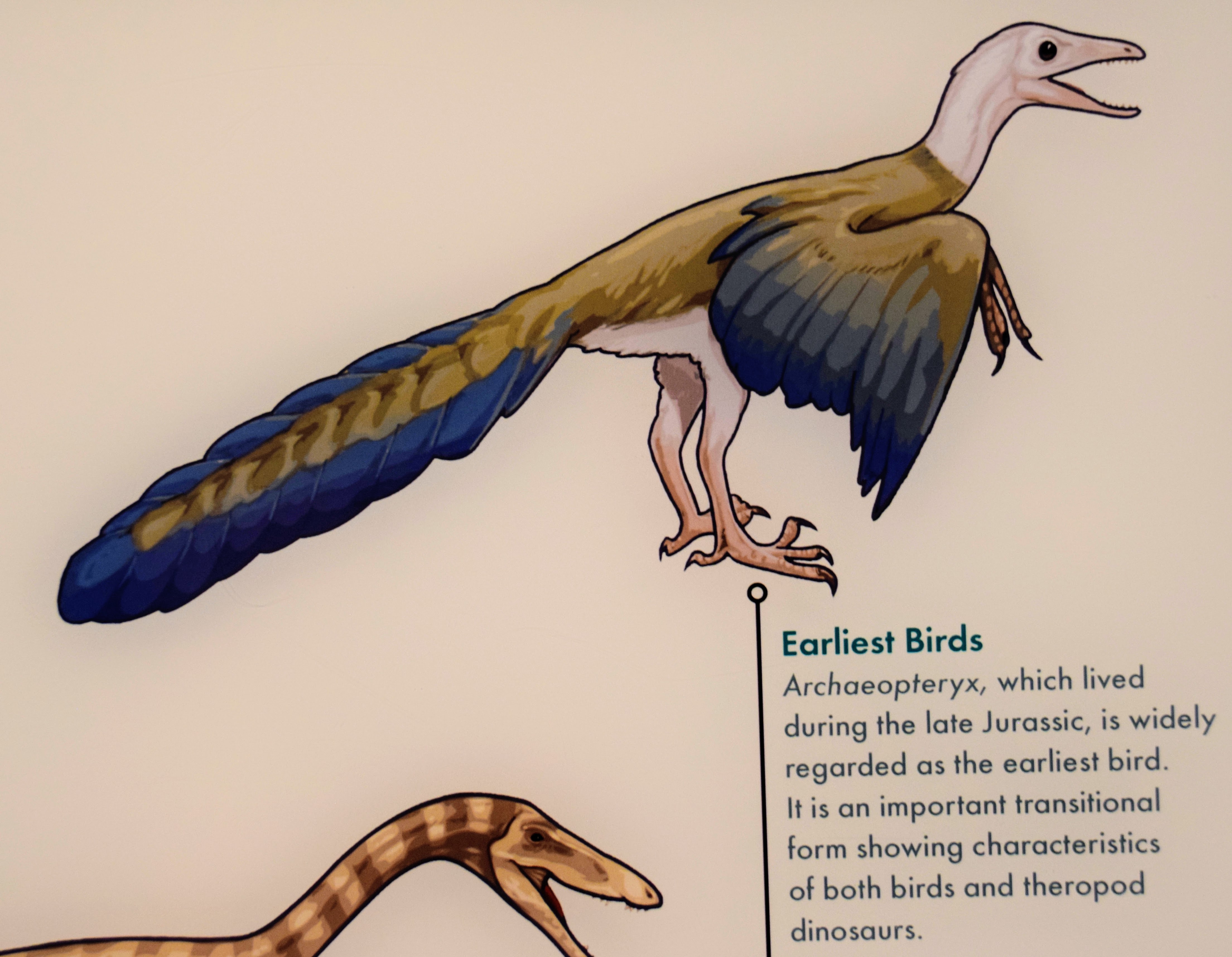

My only complaint is with the cartoony depictions of early dinosaur Coelophysis and early bird Archaeopteryx on the timeline of life in the same room. Coelophysis is shrink-wrapped and has pronated hands, and Archaeopteryx is tropey, with stereotypical blue and green body feathers and a strikingly different color on the “reptilian” body parts.

Overall, a strong start to the museum. 9 out of 10.

Early Synapsids

The next exhibit chronologically (though not in the order you’d walk through them at the museum) is the early synapsids. In the evolution room, a large pelycosaur mandible and a few small therapsid skulls are mounted alongside a diagram explaining the evolution of the one-boned mammalian jaw from the three-boned ancestral configuration. I like that they have so many illustrative transitional skulls–many are of animals that I’ve drawn in the past, such as Vincelestes and Gobiconodon–and the jaw details, while true, are maybe a little arcane for your average museum visitor. My main nitpick with this display is how they keep referring to proto-mammals as “mammal-like reptiles”, an outdated and misleading term. Mammals did not evolve from reptiles. Both mammals and reptiles evolved from a cold-blooded, superficially lizard-like amniote ancestor, but that ancestor wasn’t a true reptile. But this is a small issue.

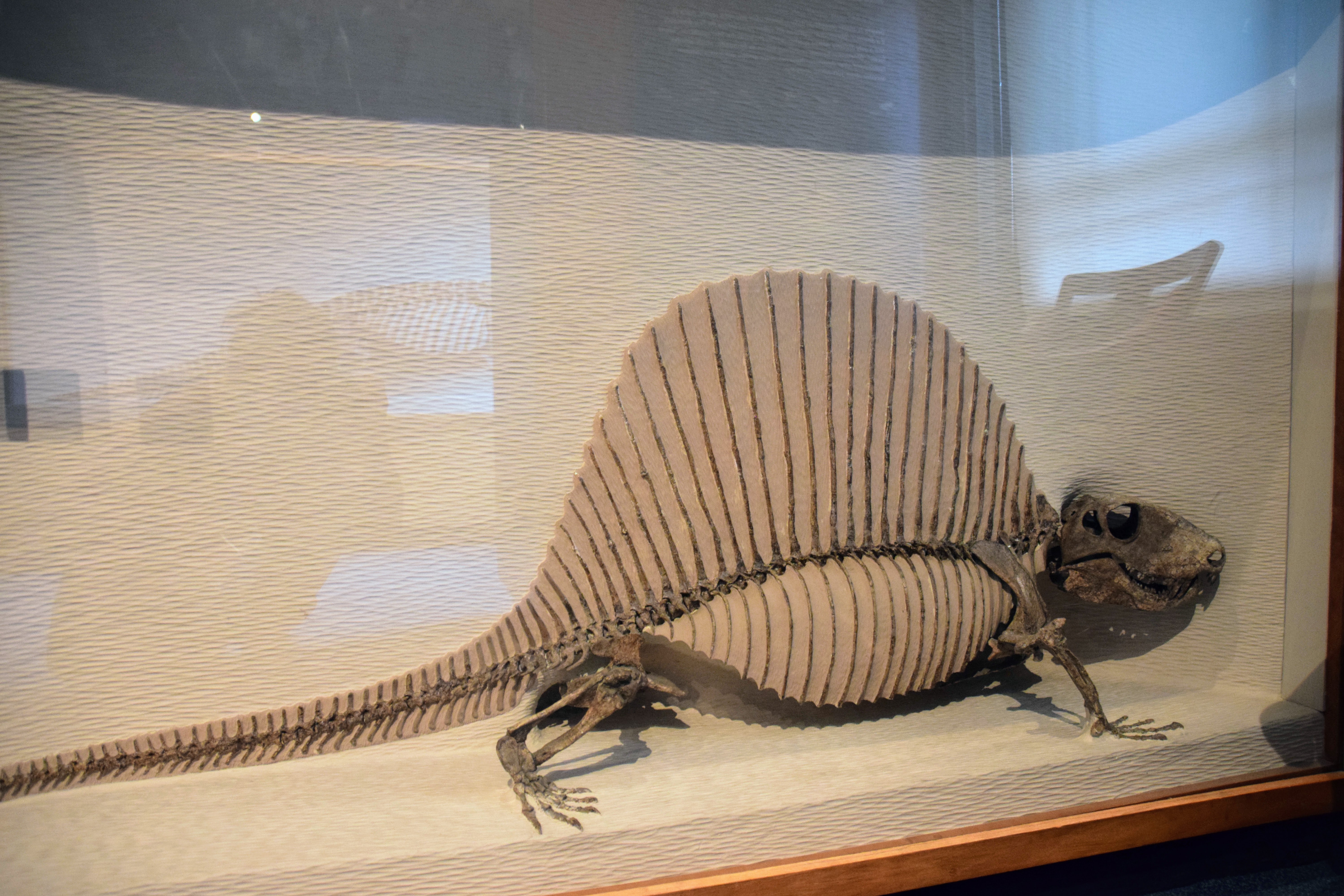

In the next room, there are three large mounted skeletons of proto-mammals: the Late Carboniferous carnivore Ophiacodon, the Early Permian sail-backed Edaphosaurus and Dimetrodon, and the Triassic dicynodont Dinodontosaurus. The first and last of those have no labeling other than the systematics (genus, species, location found, and time period lived), but Dimetrodon has a whole electronic kiosk explaining its affinity to mammals, the difference between it and reptiles, and noting the differently shaped sail spines between it and Edaphosaurus (which has cross-bars on its spines). It even says, “Despite its almost crocodilian stature, Dimetrodon is neither a reptile nor a dinosaur”, walking back the terminology they used previously to describe these creatures (“mammal-like reptiles”). The mounted skeletons themselves are well done, though they’re posed rather unimaginatively, standing in a neutral high-walk in side view.

There’s also a mural of a couple of Dimetrodon eating a Diplocaulus (the boomerang-headed amphibian–more details in my Denver Museum post) while an Edaphosaurus chews some cud and an Eryops (a large temnospondyl whose mounted skeleton is also featured in the exhibit) spaces out in the foreground.

All the depictions are decent but highly conservative. The Edaphosaurus is belly-dragging while the Dimetrodon are high-walking and dynamically seizing the Diplocaulus, indicating an active lifestyle. Both are scaly and reptilian-looking and rather drab-colored, and other than one Dimetrodon’s head, they’re completely pictured in side view and unobstructed. Since both of these animals had superexaggerated sails that were almost certainly for sexual display, they should be brightly colored or patterned; other than that, this is probably how I would have chosen to render them, but perhaps from more views or partially behind each other or foliage for better realism. Eryops is also shown in side view, and Diplocaulus in top view, which, given its strangely-shaped skull, is the easiest way to show it, and they’re both conservatively skinned and colored. Since Diplocaulus’s ridiculous head was also almost certainly for display, it should also be colored or patterned, but other than the unimaginative poses there’s nothing strictly inaccurate about this depiction.

Overall, I’d give the early synapsid display a 7 out of 10. Solid, but lacking creativity and panache.

Miscellaneous

There’s a couple of other displays in the entryway of the Romer hall before you reach the dinosaurs: early Triassic reptiles and fish through the ages. Both exhibits have a wealth of fossil material, but other than the systematics they’re unlabeled–there’s very little signage explaining what type of animal it is and why it’s important.

First, we have the wall of fish: fossil fish of all kinds from four different fossil sites. There’s a note at the beginning telling viewers to look at the panels from left to right in order to travel forward in time, and to observe how the diversity of forms increase over time. The four panels featured are labeled as being 405, 135, 40, and 45 million years old, in that order–the 40 and 45 million year panels are switched! However, the geologic formations they’re stated to come from (and the animals on display) don’t quite match the posted numbers: the Ösel Island formation actually dates to 427-423 million years ago, the Solnhofen (misspelled in the display as “Solenhofen”) formation dates to 152-145 million years ago, and the Monte Bolca formation is 50-49 million years old. The Green River formation is the only one accurately dated, listed as existing between 50 and 45 million years ago, but the numbers are backward–the exhibit says “45 to 50 million years ago”.

Adding to the confusion, some of the fossils don’t even belong in the time and place stated. For example, the Ösel Island (“An Upper Silurian Lake”) panel contains the Late Devonian fossil placoderm Bothriolepis, from Canada, which lived tens of millions of years and thousands of miles away from the Estonian Tremataspis. So much for “a point in time, a community of fish”!

Each panel has a short description of the ecosystem it’s supposed to represent, but I’d have appreciated more detail on the different fish lineages present and the ecological roles they filled. Going back to Bothriolepis as an example, this is a very unusual looking fish with insect-like armored limbs, which isn’t explained at all, and would almost certainly be unfamiliar to the majority of museum visitors and therefore difficult to visualize. And up top, the largest fish specimens aren’t labeled at all; and since they’re not inside the cases associated with the time periods, the viewer doesn’t even know when in history they lived! I’d give the fish display a 2 out of 10: lots of cool fossils, but very little by way of explanation, and incorrect and misleading information.

Moving onto the “fossil reptiles” display, we see a large, turtle-like, short, beaked skull front and center. The display is labeled “Rhynchocephalians”, which is the family of lepidosaurs containing the modern tuatara and its extinct relatives. The text next to it says that “rhynchocephalians are one of the four surviving orders of reptiles (the other three are lizards and snakes, turtles, and crocodiles)”. And the skull is labeled “Scaphonyx”.

Literally everything about this is wrong. The skull belongs to a rhynchoSAUR, not a rhynchoCEPHALIAN–a confusingly named, but completely different order of animals not closely related to the tuatara family. While rhynchocephalians are lepidosaurs, close relatives of lizards and snakes, rhynchosaurs are archosauromorphs, more closely related to crocs and birds than to lizards and snakes. Rhynchocephalians were one meter (three feet) long or less; rhynchosaurs were twice that size. Rhynchocephalians arose in the Middle Triassic and persist to today; rhynchosaurs arose in the Early Triassic and died out by the Late Triassic.

In addition to this mix-up, the five surviving orders of reptiles are rhynchocephalians, lizards and snakes (squamates), turtles, crocodylians, and birds; and Scaphonyx is a nomen dubium that stopped being used in 1983 in favor of Hyperodapedon (the first of the ’80s terms we will encounter in the museum, but certainly not the last).

The rest of the “fossil reptiles” display contains some interesting specimens, but no information other than the systematics. And since a lot of the material is fragmentary, it’s impossible for a casual viewer to have any idea what they’re looking at, and would be forgiven for thinking all of the material belonged to rhynchocephalians. Other than the actual rhynchocephalian material, the other items in the case include an Eocene snake segment, a Megalania (giant monitor lizard from the Pleistocene) vertebra, and a crushed Tylosaurus (predatory marine lizard from the Cretaceous period) skull. Absolutely zero information is presented other than the systematics, not even the parentheticals I just included. It seems that the display designer intended to contrast squamate diversity with rhynchocephalian diversity, splitting them on the left and right halves of the panel, but this isn’t explained at all. 1 out of 10, extremely bad display. In fact, I thought this mislabeling was so egregious I filed a complaint at the front desk on my way out.

Hall of Dinosaurs

Finally, we’ve reached the dinosaurs. The first one on display is Deinonychus, the famous “raptor” dinosaur that helped to kick off the Dinosaur Renaissance and inspired the “Velociraptors” of Jurassic Park. This mounted specimen is somewhat fragmentary, but it has the important parts: the ossified tendons along the tail, the skull complete with sclerotic ring (eye bones), and one arm and one leg.

It’s reconstructed in front of, and in the style of, the illustration from the 1976 paper by the dinosaur revolutionary John Ostrom describing this particular specimen. It’s very cool that they have one of Ostrom’s fossils, given how influential it was in shaping our modern perception of dinosaurs. It’s also a cool idea to mount it in the original published pose. There’s a short paragraph on the glass about Deinonychus’s physiology, but no information about why this specimen is special and how it helped push paleontology forward. And since this paper was published in 1976, there’s a lot about the pose that is outdated, such as the hyperextended ankle and pronated wrists, which I think would be helpful to point out to viewers. 8 out of 10.

Next is a cabinet full of miscellaneous dinosaur specimens, including a Corythosaurus (crested “duck-billed” dinosaur) skull, a complete articulated Heterodontosaurus (primitive small herbivorous dinosaur) skeleton (below), a smashed Ceratosaurus (primitive large, crested meat-eating dinosaur) skull, and a Coelophysis (primitive small meat-eating dinosaur) skull. There’s a small note on the display, which I unfortunately didn’t get a picture of, which describes the difference between ornithischian and saurischian dinosaurs, but asserts that they are two different families that don’t share a single common ancestor. That view, of Dinosauria-as-polyphyly, was popular up until the mid-80s. For the past 36 years or so, it’s been the scientific consensus that Dinosauria is actually a natural group. Since this museum opened in 1998, I’m confused why this outdated information would have made it into the display. Other than that, there’s no information about the individual specimens that would help the viewer interpret what they looked like or how they lived. 4 out of 10.

After that, there are the museum’s two most prized possessions: the first Triceratops skull ever unearthed, and the world’s only mounted Kronosaurus skeleton. As usual, neither has any accompanying text. It’s a shame that most viewers can’t appreciate the historical importance of these specimens.

The Kronosaurus skeleton is really breathtaking. It’s two-thirds original fossil material, and nearly 13 meters (42 feet) long. It takes up an entire wall, and it’s difficult to take it all in from a single perspective.

This specimen has a rather tangled history, though. It was illegally expatriated from Australia, where it was found, and reconstructed in a somewhat biased way in an attempt to maximize its impressiveness. Since the skeleton was so large, it had to be split apart in order to be unearthed, and in the operation the exact number of vertebrae became unclear. The preparators inserted the maximum number of plaster vertebrae allowable by the scientific error bars, resulting in the 13-meter beast; more modern estimates fall closer to the low end of the original, and we now believe it should only be 9 or 10 meters long. A mysterious chunk of bone found near the head was interpreted as a tall sagittal crest on top of the skull that would have anchored powerful jaw muscles, but based on additional specimens of Kronosaurus we now believe it wasn’t part of the skeleton at all, and the animal had a shallower, more streamlined skull.

Correcting these issues would be an enormous endeavor, so I don’t blame them for leaving Kronosaurus as it is. But I’ll still deduct a couple points. 6 out of 10, mainly due to the lack of information posted.

Last in the Romer Hall is a mounted skeleton of the basal sauropodomorph (early long-necked dinosaur) Plateosaurus and a bunch of miscellaneous Triassic archosauromorphs (relatives of crocs and dinosaurs, but outside the direct lineage).

The Plateosaurus is lovely, but old-fashioned in its pose. It’s reared in a kangaroo-like stance with its tail dragging on the ground, and its hands are pronated (palms facing the ground). This arm position is achieved by rotating the humerus (upper arm) too far inward and then swapping the places of the radius and ulna (lower arm bones); the radius (larger of the two lower arm bones) should terminate on the thumb side, not the pinky side.

The “thecodonts” next to the Plateosaurus include a couple of proterochampsian skulls, Gualosuchus and Chanaresuchus (a group of small croc-like Triassic reptiles), a phytosaur skull, Machaeroprosopus (one of a group of large croc-like Triassic reptiles), a protosuchian skull, Gracilisuchus (one of a group of very small, fox-like croc relatives), and a sauropod egg. While the case labeled “Fossil Reptiles” contained lepidosaurs (lizard relatives), this display contains archosaurs (croc and dinosaur relatives), the other major branch of the reptile family tree. Unfortunately, neither exhibit has signage to enlighten you to this organizational structure.

The word “thecodont” means socketed teeth, which is a description of one of the ways teeth can grow in a vertebrate’s jaw (the other ways being acrodont (teeth fused to the top of the jawbone) and pleurodont (teeth on a shelf on the inside of the jawbone)). But in the ’80s and earlier, “Thecodontia” was the name given to the family including most archosauromorphs and crocs, but excluding dinosaurs and birds. Since dinosaurs are nested deeply within this family, “Thecodontia” should include dinosaurs if it were to be a monophyletic clade. Accordingly, some scientists tried to redefine the term “thecodont” to include dinosaurs, but confusion between the old and new usages resulted in the term being dropped from the scientific lexicon by the end of the 1980s (except as an adjective describing socketed teeth). This is another example of over-30-year-old information being presented here, which doesn’t make sense because the museum is only 24 years old. 5 out of 10.

Cenozoic Mammals

I won’t dwell too much on the Cenozoic mammals since this post is already quite long, this is a dinosaur blog, and I’m not an expert on Cenozoic mammals so I’m less able to evaluate the quality of the educational material. The mounted skeletons of early horses like Mesohippus, the giant armadillo relative Panochthus, the weird horse/gorilla Moropus, and the pantodont Coryphodon are very cool, complete, and awe-inspiring (though they’re all mounted in a neutral side view). You can see photos of all the mammals on display, and some of the dinosaurs, here.

I’d just like to call attention to the sign in the entryway of the Cenozoic mammals exhibit. There’s a family tree showing the relationships between modern ungulate species and the time in history the different families branched off. Unfortunately, it’s completely made up.

Nearly everything about this tree is false. First of all, elephants and kin are not ungulates; literally all other placental mammals are more closely related to ungulates than the elephant family is. If elephants are included in a family tree alongside horses, then cats and dogs, monkeys and humans, rodents, bats, etc should be included as well. I think the reason elephants and kin are included in this sign is because the writer was confused by the similarity of names given to these groups: elephants and kin are in the family Paenungulata, while rhinos, cows, whales, and kin are in the family Ungulata. The names come from the fact that the word root “ungul-“ means “nails”, since many of these animals walk on nails modified into hooves.

Next, the evolutionary relationships depicted on this sign are all screwed up. Cetaceans (whales) are more closely related to ruminants (deer, cows) than either is to camels or pigs. Camels are more distantly related to the ruminants and cetaceans than pigs are, so those two branches should be switched. The elephant family is shown here nested within the whale family, which makes absolutely no sense, and perissodactyls (horses, rhinos, and tapirs) are nested within the hyrax family. What?? Who the heck made this sign?

And what do the thicknesses of the bands mean? I would imagine it means number of genera over time, but the horse-lineage band (containing one genus, Equus) is thicker than the pig-lineage band (containing nine genera), so that can’t be right. Pigs definitely outnumber horses in terms of current population as well, so it’s not that. Is it just a made-up number to make the chart look more legitimate?

Zero out of 10 for this sign. But the sign looks very nicely made and relatively modern, so I think it would be challenging to correct. Hopefully visitors don’t look too closely at the tree…

Conclusion

Overall, I was disappointed with the educational material in this museum, but impressed by the fossils. They have enough fossils to provide a really high quality experience–and they even have historically important fossils, something most museums don’t have access to even if they tried–but it’s mostly squandered with outdated, sparse information. I’m going to try to contact someone who works there and help them rewrite some of their Romer Hall labels, and maybe supplement them with additional ones. There’s an opportunity here for a really great exhibit. Hopefully they’re open to trying to improve!