If you’ve hung around this blog for awhile, you may have seen my participation in Inktober in 2019 and 2020 (and last year, Botober), the month-long event in which every day there’s a different prompt, which participants use as inspiration for a daily ink drawing. I’m a little burnt out on Inktober (I prefer digital art), but I did want to do some kind of art challenge. So this year I’m doing “Spectember”, a speculative evolution event! Speculative evolution is when you either take a concept, such as “life on a high-gravity world” or “what if another group of vertebrates could fly” or “what kind of animal would be the best triathlete”, or an end result, such as Godzilla or creatures from a certain viedo game, and try to use the real constraints of evolution and actual living things to explain or create an organism.

Here are Spectember’s prompts:

I’m going to do most of them, but not all–some of the prompts that reference outdated concepts or just don’t spark inspiration for me, I’m going to skip. If you haven’t been back to this post in awhile, Spectember is now complete, so scroll to the bottom to see new art!

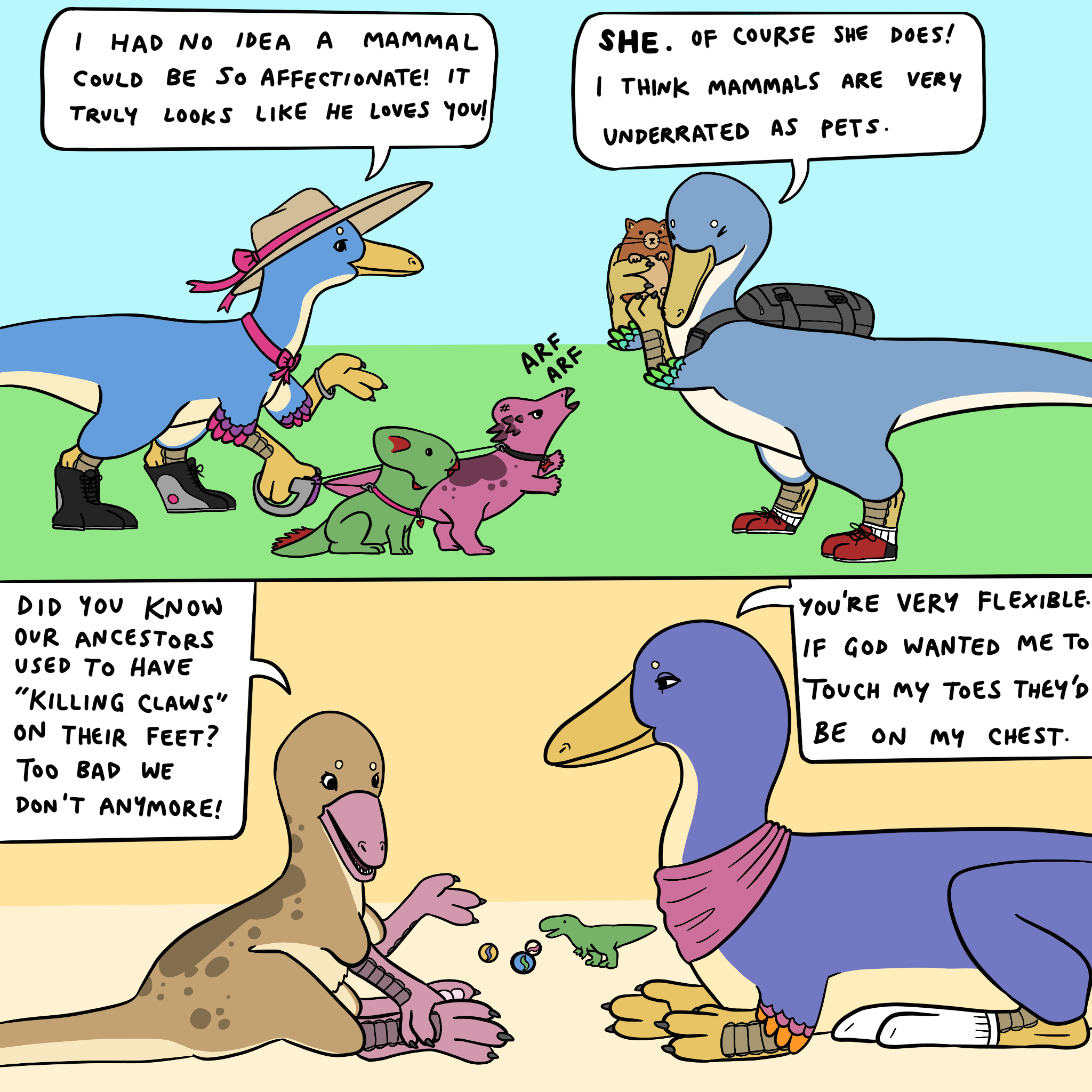

Before we get started, here are some cartoons I made featuring a very famous speculative evolution creature: “dinosauroids”, the intelligent species that results if the asteroid had not wiped out non-avian dinosaurs. They’re descendants of a “raptor” dinosaur, or possibly even an early bird, which were the smartest animals at the end of the Mesozoic.

Day 1: Robust Reptiles

Pareiasaurs were a group of early reptiles from the Permian period, 265 to 252 million years ago (the last period before the Mesozoic Era, or Age of Dinosaurs). They were large, bulky herbivores that often had osteoderms (bony armor), bumpy horns on their heads, and an upright posture. They went extinct, along with most Permian animals, in the Great Dying, the mass extinction at the end of that period.

If a small group of them made it through the Great Dying, where would they be today? We no longer have any cold-blooded megaherbivores, so I tried to think of a role in which ectothermy would be an advantage. Bulk feeding of poor-quality fodder might be one such niche, but ungulates have grasslands on lock, and ectotherms can’t exist above certain latitudes. So, my pareiasaur descendant is a pine needle specialist that lives in the temperate conifer forests of the Pacific Northwest. Hardly anything eats pine needles in real life, so it’s free real estate!

The “nothro” in Nothropareia means “sloth”, since the animal ended up looking a lot like a reptilian version of a giant ground sloth. Perhaps slow metabolism was one reason sloths were so good at the megaherbivore role in the past–Nothropareia would have done it better!

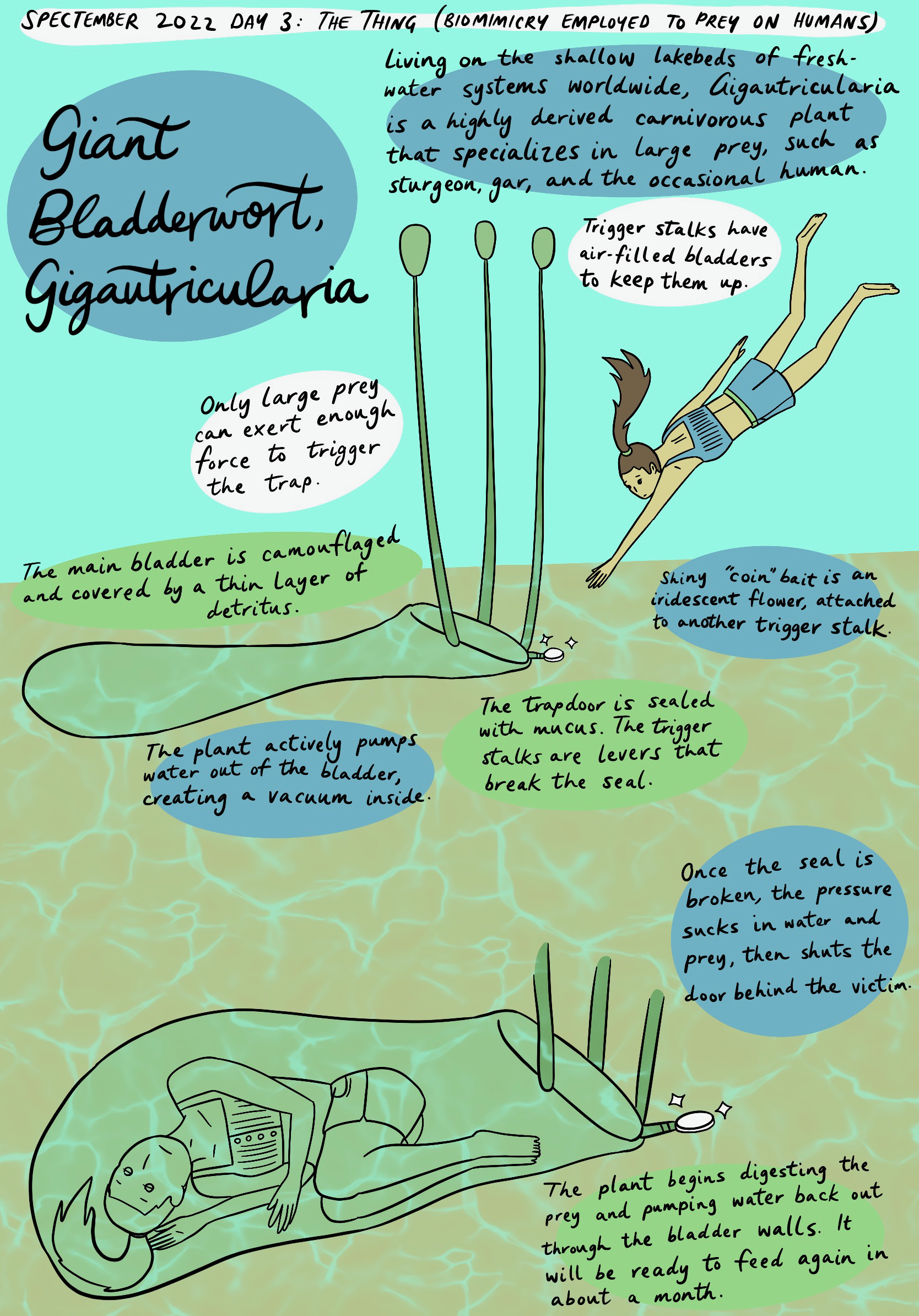

Day 3: The Thing

I haven’t seen the movie The Thing, but I’m pretty sure it doesn’t technically use biomimicry–it’s more like a body snatcher–and it also doesn’t limit itself to preying on humans. Anyway…

Bladderwort is an aquatic carnivorous plant with a worldwide distribution that deserves more recognition. Everyone knows of Venus fly traps and lots have heard of pitcher plants and sundews, but there are two other kinds of carnivorous plant that are less well-known: lobster pots, which are kind of like horizontal pitcher plants that have sharp, inward-angled spines that allow the prey to move forward along the tunnel but not backward, and bladderworts, which have definitely the coolest and most complicated trap. Each tiny trap, of which each plant has hundreds, consists of a pouch, a trapdoor, and trigger stalks. The plant actively pumps water out of the pouch, creating a vacuum inside; the trigger stalks are just mechanical levers that break the seal, allowing water to rush in. Contrast this with the Venus fly trap, whose trigger hairs act more like an animal’s nervous system by sending a signal to the hinge to prompt it to close. In a bladderwort, the only active part is pumping out the water; then the trap is set and the plant can just sit back and enjoy its tiny meals.

A giant bladderwort maybe could have evolved by incrementally targeting larger prey: first it would go from rotifers to arthropods, then to small fish, then larger fish, and so on (which means that if a giant bladderwort exists, then a large, medium, and small bladderwort probably exist alongside it). As its bladders get bigger, they get fewer, until the giant bladderwort only has one trap left.

Utricularia is the genus of real bladderwort, so Gigautricularia just means “giant bladderwort”.

Some people have informed me that this looks like “vore”, a fetish some people have for things eating girls. I apologize, any similarity is unintentional.

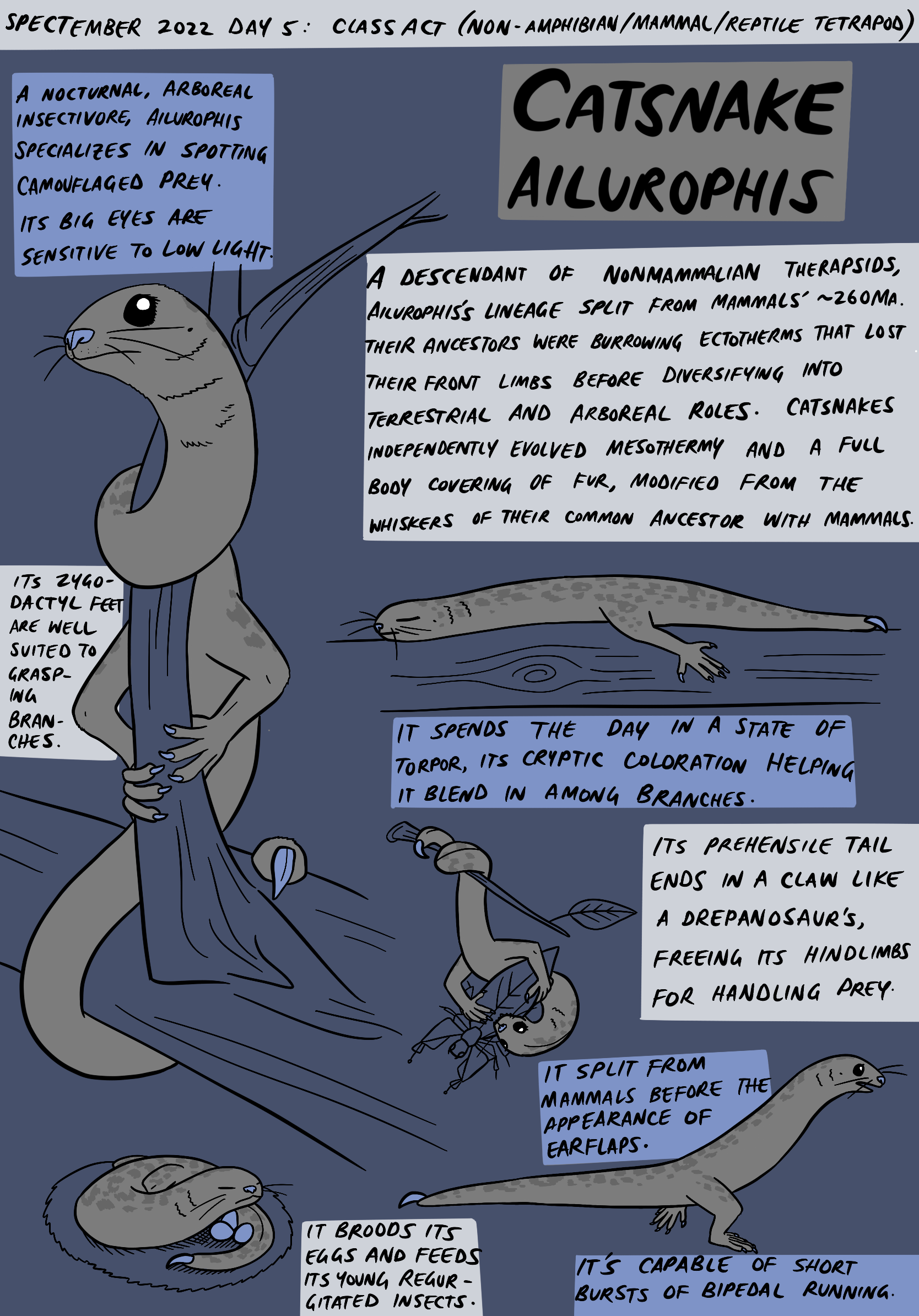

Day 5: Class Act

Since the tree of life is constantly branching, taxonomic “levels” like Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, et cetera, are mostly meaningless. The only level with any real-world meaning is Species, defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two of appropriate genders could mate and produce fertile offspring, but even that has exceptions.

The five commonly cited “classes” within vertebrates are fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. However, as I’ve discussed before, birds nest within reptiles, and all of them nest within fish. Enough about the letter of the prompt though, what’s the spirit? Reptiles and birds, the most closely related distinct “classes”, last shared a common ancestor around 247 million years ago, in the Middle Triassic. So any “sixth class” should share a common ancestor that far back, or earlier.

I always thought it was unfair that reptiles got two “class” entries and mammals only one. So here’s my take on a mammal-like animal that split off from the mammal lineage during the Permian. It’s a therapsid, but not a cynodont; other than that I didn’t have anything specific in mind as its direct ancestor.

Ailurophis literally means “cat snake”.

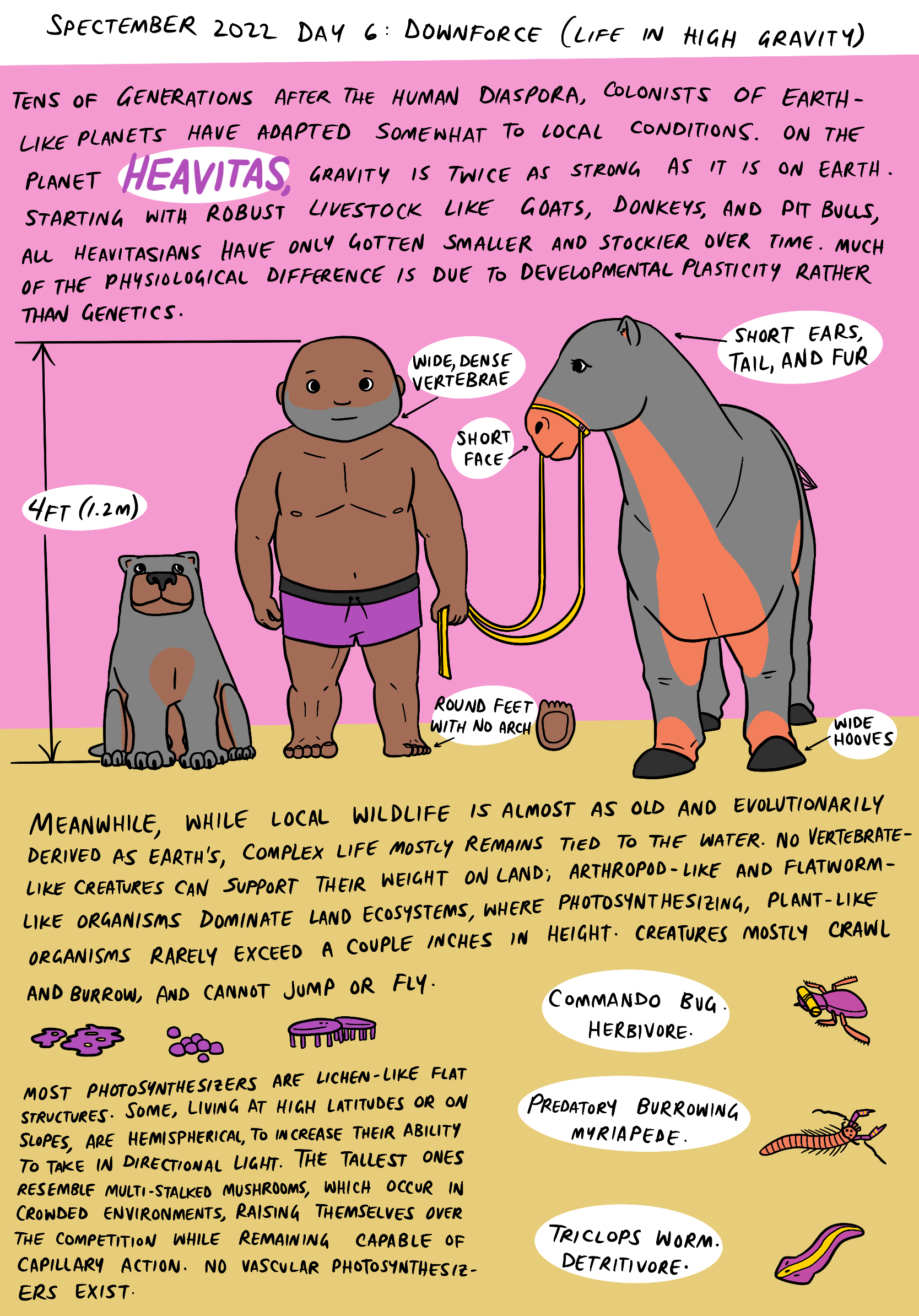

Day 6: Downforce

This one has a lot of text on the card, so I’ll just let you read that instead of overexplaining here.

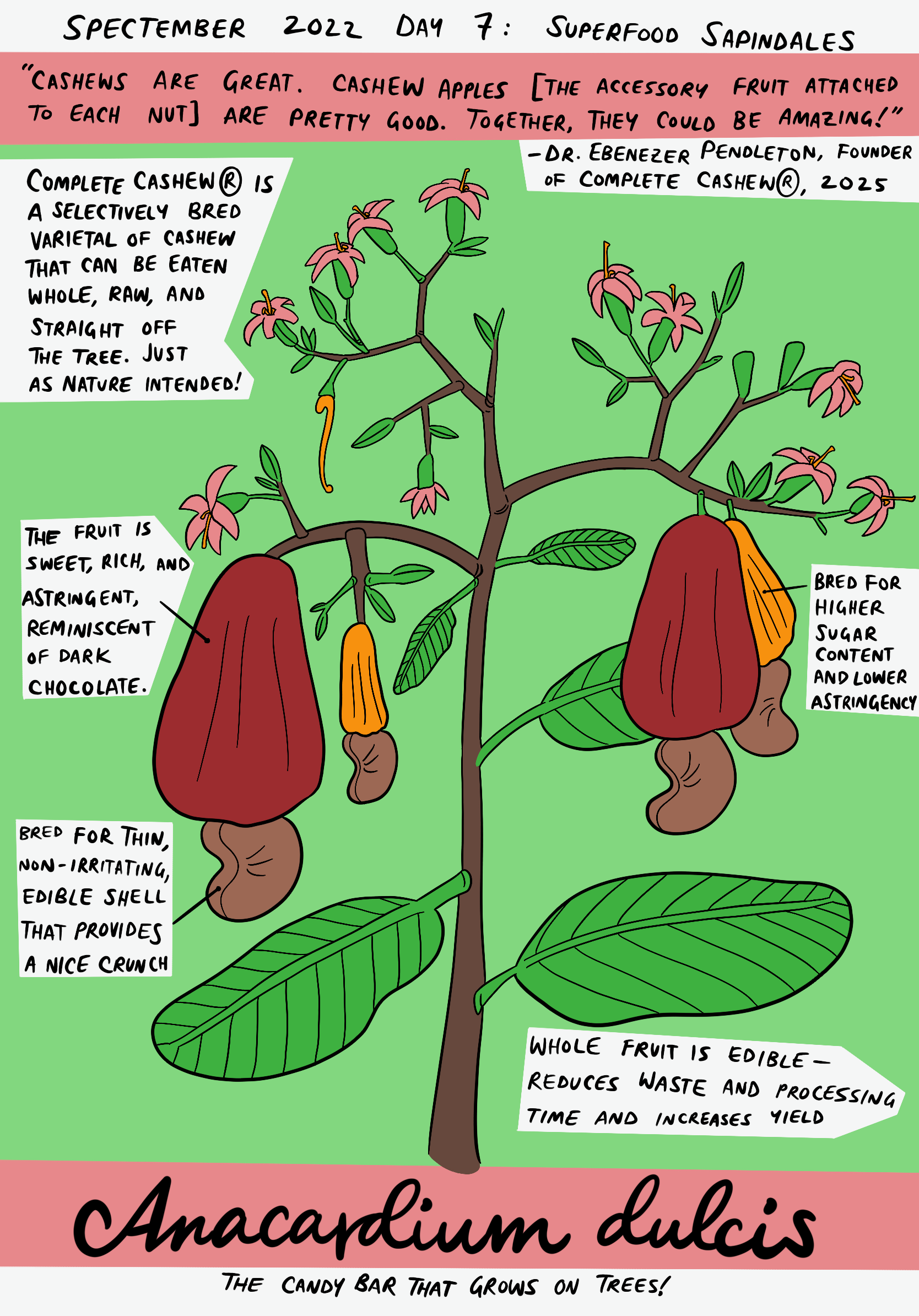

Day 7: Superfood Sapindales

Sapindales (pronounced sap-in-DAY-lees) is the family of plants containing citrus, lychee, mango, maple, cashew, and many others. I’m not sure why the r/SpeculativeEvolution people chose this particular family as the source of our new super-crop, but there you are.

In real life, each cashew nut is encased in a shell that causes a poison-ivy-like reaction, and is attached to a small accessory fruit known as a “cashew apple” that’s said to taste something like a bland peach or a crunchy plantain that makes your mouth leathery. It’s commonly made into pastes and jams in South and Central America, but not widely known elsewhere.

Whenever people advocate fruit or fruit juice as a health food, I remind them that fruits are evolutionarily supposed to be as tasty as possible, not particularly healthy. If a plant could grow a Snickers bar, it probably would. So this is my attempt at speculatively evolving that.

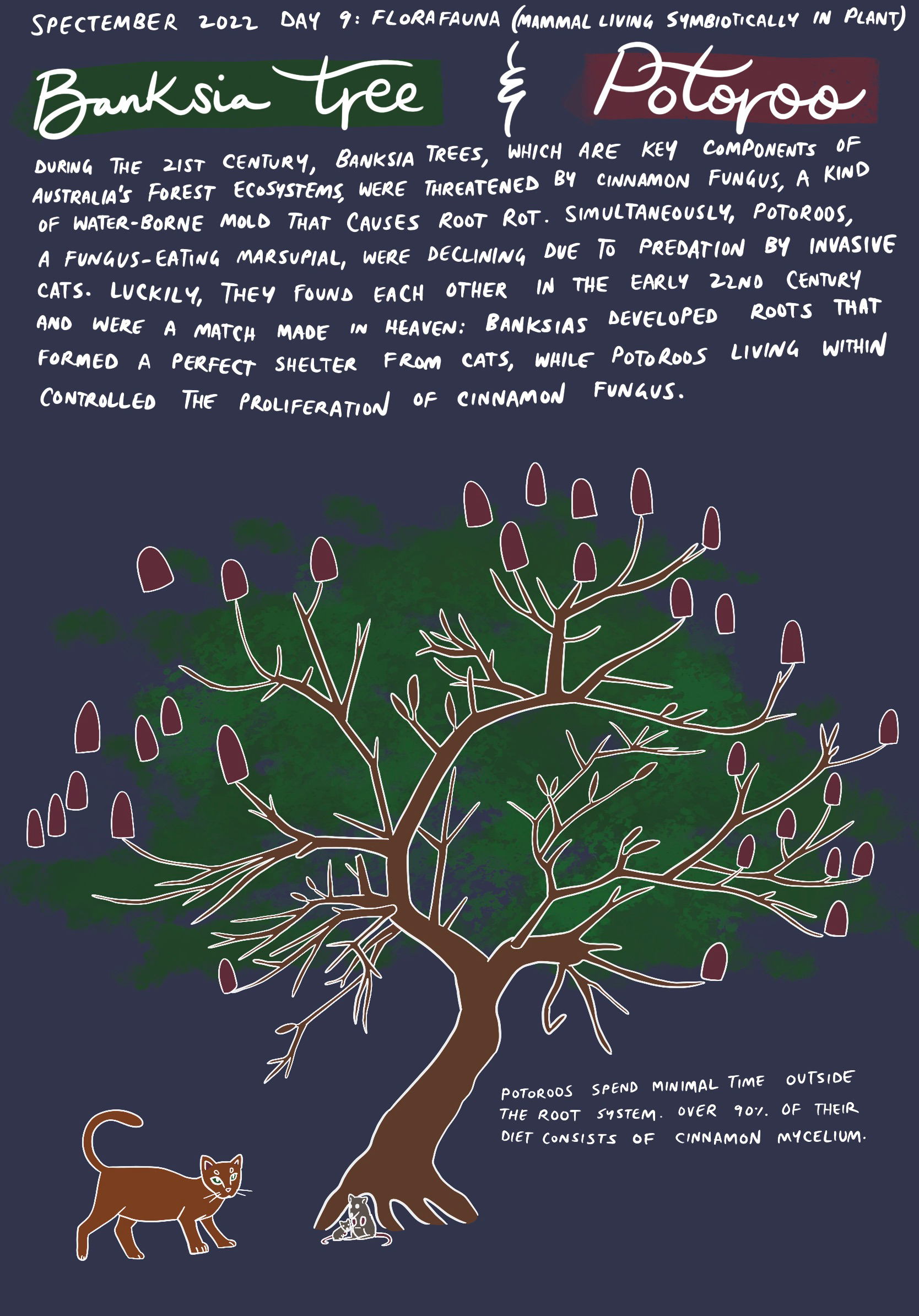

Day 9: Florafauna

Mammals living inside plants in a mutually beneficial relationship already happens in real life: Indonesian wooly bats make their roosts inside normally carnivorous pitcher plants, which provide shelter in exchange for nitrogen-rich bat poo. However, I wanted to do something completely different.

The spread of cinnamon fungus Phytophthora cinnamomi is currently wreaking havoc on Australia’s forest biomes. It’s treatable, but incurable, and since a lot of these forests are quite remote, the fungus is mostly spreading unchecked through wild lands. It’s quite versatile, and able to infect all kinds of trees, some of which are important crops, like avocado.

Potoroos and bettongs are rabbit-sized bipedal marsupials native to Australia that are some of the only mammals to specialize on eating fungus. In real life, they mostly eat mushrooms, which are the fruits of fungus, rather than mycelium, which make up the main underground body, and sometimes even run through plant cells. I’ve left the mechanism by which potoroos are able to extract mycelium without harming the plant up to the reader’s imagination.

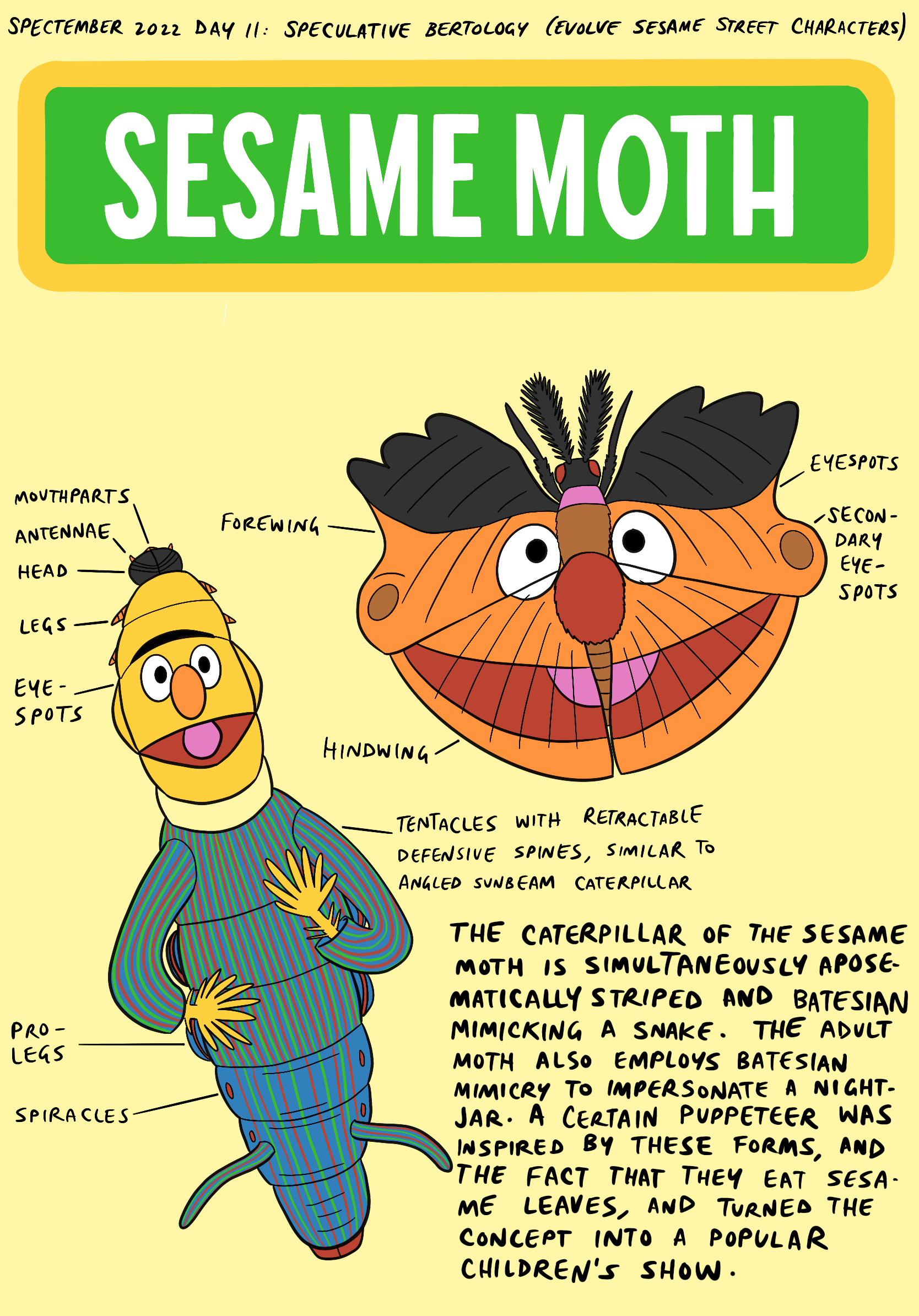

Day 11: Speculative Bertology

I’m really curious to see what other people come up with for this one. Aliens? Future descendants of humans that have fewer fingers and exaggerated facial features?

Edit: Someone made a hilarious “Elmopithecus” ape. Why is Elmo red? Because his prey are red-green colorblind…

As unlikely as this seems, caterpillars and lepidopterans (butterflies and moths) do a lot of very strange things when it comes to coloration, body structures, and mimicry. Some caterpillars have retractable tentacles, horns, or brushy structures that they use for defense; others are covered in toxic spines, irritating hairs, or shape-concealing fluff. Some have structures that look like convincing snake heads, and one of them is literally the Pokémon Caterpie.

Aposematism is when something dangerous or toxic has flashy colors or patterns as a warning to would-be predators. Batesian mimicry is when something not dangerous imitates something dangerous. Mullerian mimicry is when multiple dangerous things look the same as each other, so that predators only have to learn one type of pattern to stay away from (like bees and wasps with their warning-sign yellow and black stripes).

Day 12: Ghost Lineage

A ghost lineage is when a certain species or group disappears from the fossil record for a time, then reappears later. They continued living during the gap, as evidenced by their surviving descendants, but we don’t know at all what they were doing during that time. One famous ghost lineage is coelacanths (pronounced SEE-la-kanth), a type of deep-water lobe-finned fish. There aren’t any fossils of them younger than Cretaceous, so they were thought to have gone extinct alongside the non-avian dinosaurs, but then living specimens were found off the coasts of India and Africa. They were so similar to the fossils that they were instantly recognized; however, the group was already named “coelacanths” and the genus name Coelacanthus was already taken, so the living ones were named Latimeria.

Anyway, you get a BOGO on this prompt: two ghost lineages for the price of one! I went with mesonychids, a family of carnivorous ungulates (relatives of horses, sheep, and whales) that lived during the Paleogene (65-30 million years ago), and taeniodonts, a family of cimolestans (early non-placental eutherians) that lived from the Cretaceous to the Eocene (74-40 million years ago). I picked those because they’re both rather specialized and quite different than anything we have today.

Real mesonychids never achieved true unguligrady, but rather were digitigrade with hoof-like nails. They were also paraxonic (bearing most of the weight on the two center toes), similar to sheep and pigs, but hadn’t reduced their total number of toes. My modern mesonychid, given 30 million more years to refine itself, is truly unguligrade and has two toes and a dewclaw per foot. It’s also further developed its dentition for its carnivorous lifestyle, with a very wolf-like set of teeth.

Real taeniodonts had strong forelimbs with large claws for burrowing, and ever-growing incisors that were, unusually, derived from their canines. However, counterintuitively, they probably didn’t eat roots and tubers, as wear on their teeth doesn’t match that lifestyle. Instead, they probably dug burrows, but ate something else unknown. My taeniodont does eat roots and tubers, fulfilling its destiny.

Day 14: Herbilingua

The scientific name for the anteater family is Vermilingua, or “worm tongue”, referring to the fact that their tongue looks like a worm, not that they eat worms (they eat ants…obviously). So the moniker “Herbilingua” isn’t quite right for an herbivorous anteater; if I were following the title, I should evolve an anteater with a leaf-shaped tongue. But enough pedantry, let’s get to the actual content.

While the giant, terrestrial anteater is probably the most well-known, other anteaters, including the tamandua and the silky anteater, are arboreal and have very sloth-like claws. (This makes sense, as sloths are anteaters’ closest living relatives.) Since they’re already arboreal, small, and equipped with claws used for tearing wood to get at insects, it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine them supplementing their diet with some tree sap they incidentally dig up, and then relying on it more and more over time. And why not throw in a gliding membrane? That’s always a useful thing to have for an active, arboreal lifestyle. And…I’ve just created another version of a sapsucker (bird) or sugar glider (marsupial). At least it’s plausible!

Day 15: Endangered Enigmatic

Mountain animals escaping global warming by living at higher elevations is already happening; what if it happened on the highest peaks in the world?

These are the descendants of the markhor and the red agama, two animals that currently live at medium elevations in the Himalayas. The markhor is an impressively statuesque type of mountain goat that’s a stenocline, an animal that is adapted specifically for one elevation, rather than a eurycline (such as a vicuña, an Andean alpaca relative) which would tolerate a variety of elevations. If the climate change is slow enough, the elevation the goat is adapted to could match pace with the changing temperatures, and it could end up very high up indeed.

Lizards don’t live where it’s too cold, since they rely on ambient temperatures to warm them enough for their body’s chemical reactions to function. However, if global warming made elevations not so snowy, the main problem left to confront is lack of oxygen, which is actually something ectotherms (cold-blooded creatures) do better than endotherms (warm-blooded ones). Perhaps alongside the mountain agama, there are lots of other lizards populating the balmy slopes of Everest.

Day 17: Natural Wonders

Glass sponges are a type of sponge (asymmetric, filter-feeding animals) that support their flesh using little bone-like structures known as spicules (small spikes) made of silica (literally glass). Viewed under a microscope, they’re shaped like little caltrops, dumbbells, and other strange and exotic shapes. However, most are too small to be seen with the naked eye.

Enter the Giant Basal Spicule sponge, Monorhaphis. This real, extant, non-speculative animal creates a looooong, thin, pole-shaped spicule (shouldn’t we just call it a spike at this point? There’s nothing -ule about it) that holds the animal far above the sediment, to improve its filter-feeding efficacy. Filter feed too close to the seafloor and you get clogged with mud; a little higher and you’re competing with lots of other filter-feeders. The GBS (as it’s known in scientific papers) is the sponge’s equivalent to a tree’s trunk, raising its important bits above the competition.

In the past, glass sponge spicules piled up and formed reefs (one of many non-coral reef-builders from prehistory), but in the modern day corals dominate in structure-building duties. Here’s where my tiny bit of speculation comes in. Por que no los dos? Giant spicule reefs! It would be like enormous aquatic pickup sticks.

Interestingly, silica is a lot less plentiful in the environment than calcium carbonate (seashell material) or calcium phosphate (bone). So GBS sponges grow really, really slowly and can live tens of thousands of years.

Day 18: Bonanza

This one is a reference to an unsubstantiated but famous theory known as “the aquatic ape hypothesis”. The hypothesis was that perhaps the reason humans are hairless and upright-standing is because our ancestors were semiaquatic apes?

No evidence at all supports this, and I’ve written a little bit about why we did lose our hair in a previous post. (I’ve also written about why apes can’t swim in a different post.) However, what might an aquatic ape actually look like?

Apparently like green Donkey Kong… (It’s green because its fur is full of algae, like a sloth. The algae don’t help or harm the ape other than camouflage.)

Day 19: Flight School

I’m happy with how this turned out, but there’s no way I was going to do something better than Osmatar’s Sharovipterosaurs.

Anyway, for this prompt I didn’t want to do any mammals or ornithodirans, since those are over-represented in real life. Nor did I want to do a new kind of flying bug, since I’m not familiar enough with inverts to do a good job. I considered flying frogs or snakes since there’s already a gliding version (gliding frogs use their big webbed feet like little parachutes, and gliding snakes make their body into the cross-section of a Frisbee), but ended up settling on flying fish. While “flying” (gliding) fish today are from the order Beloniformes and don’t breathe air, there have been gliding fish found in the fossil record from an unrelated family, the extinct Triassic Thoracopteridae, indicating that fish gliding isn’t too hard to evolve. Therefore, I’ve picked a third group of fish to be my powered fliers–the blennies, a type of semi-terrestrial fish that already has a lot of the traits needed to make a good aerialist. They can jump using their tails, support their weight on their pectoral fins, and, most importantly, breathe air (as long as their skin is moist).

Day 20: Inner World

Whew, four days in a row. I’m falling behind!

As I mentioned a couple posts ago, the smallest known tetrapod is a teeny tiny frog called Paedophryne, which is about 7mm long and lives among leaf litter. It’s less than a tenth of the mass of the smallest known amniote, a tiny gecko called Sphaerodactylus, which indicates that amphibians are just able to achieve smaller sizes than amniotes, though I’m not sure why. I don’t know too much about parasites, so let me know if this doesn’t make any sense. “Cestoides” means “belt-like”, in reference to Cestoda, the scientific name for tapeworms.

After I posted this on Reddit, people asked some good questions, so I’ll also answer them here.

How does it breathe? – I honestly didn’t think about this, but since it already sucks blood I’m going to say that it absorbs oxygen through the skin of its mouth and face while it does that. Many frogs already breathe through their skin, and these frogs would not have very high oxygen requirements because they don’t move around very much.

Why not just stay a tadpole? Then it would be better able to swim in the digestive tract. – That is a good point. Some amphibians have neotenic development, like the axolotl, which stay in their tadpole phase their whole lives. However, the ancestor I chose, Paedophryne, already doesn’t have a tadpole stage, so it would be one more thing to change. And, since the prompt is “an endoparasitic tetrapod”, the four-legged frog shape fits the bill a bit better than a fishlike tadpole. Neotenic development seems easy for amphibians to evolve though, so maybe it does make more sense here.

Day 22: No More Tentacles

The vampire squid is a deep-ocean cephalopod that’s more closely related to octopuses than to squid, but isn’t particularly close to octopuses either. It has weird, super-long filaments it uses to snag marine snow (tiny bits of sinking detritus) and tentacles partly connected by a “cape” of webbing that it uses to grab soft-bodied prey like jellyfish and salps. It also has enormous eyes for seeing in the dark, and bioluminescent patches on the tip of its mantle and on the tips of its tentacles, as well as the “glitter bomb” glowing mucus attack it uses instead of ink.

My vampire squid descendant is convergent with jellyfish, having become slower and more passive over time to save energy.

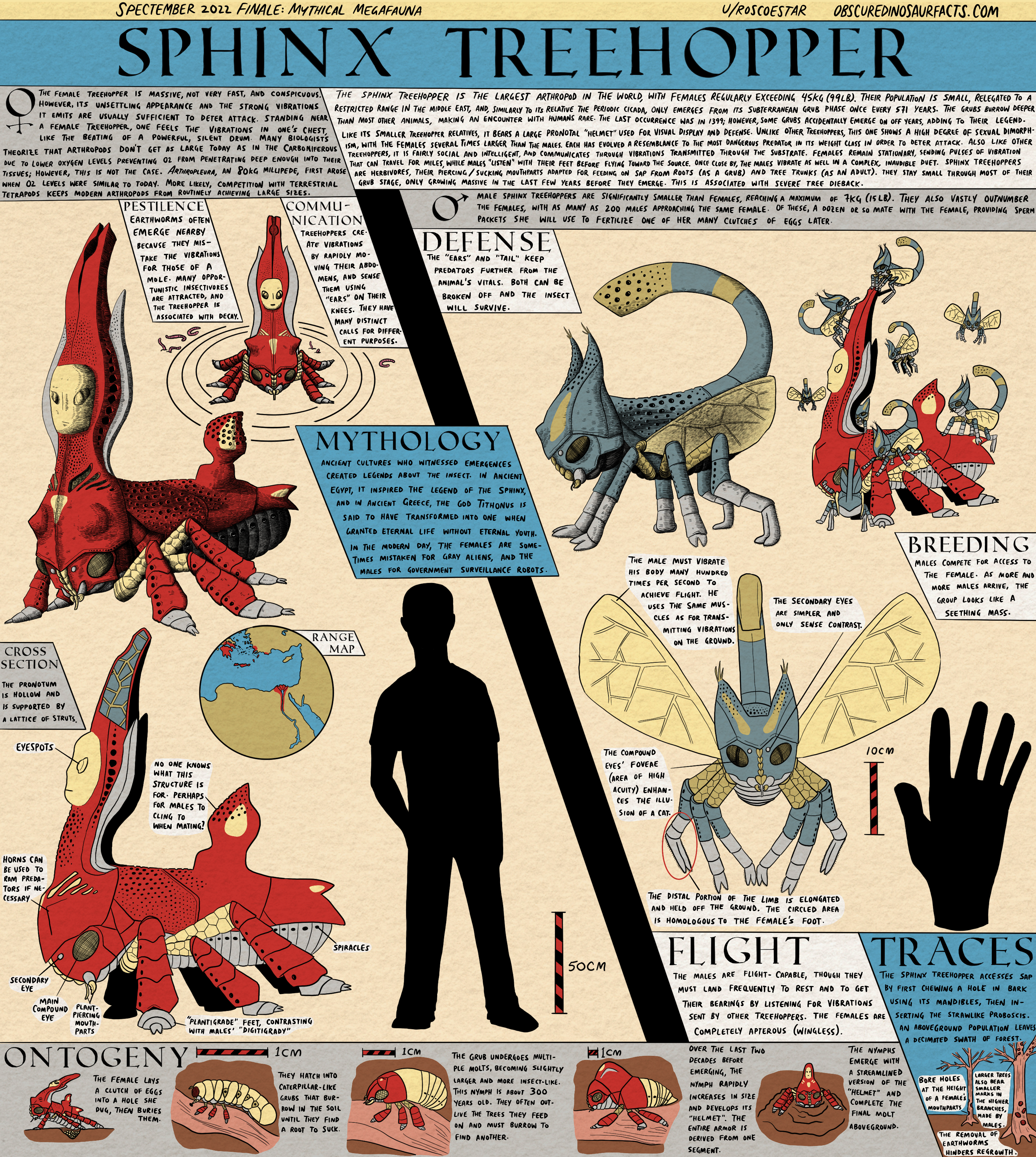

Finale: Mythical Megafauna

The last entry in Spectember is a special, high-effort one that will be judged in a contest. Here’s the prompt:

Five insets in addition to the main depiction of the animal sure was a lot! Here’s what I ended up with.

The contest will be judged after a week of user engagement on Reddit, so if you want to ask me a question or throw me an upvote head over there before October 7 at 00:00 UTC (October 6 at 5pm PDT). I’ll let you know if I win :)