There are lots of famous examples of mutualism, or two species cooperating to the benefit of each, in nature. Flowers and pollinators. Cleaner wrasse and sharks. Trees and mycelium. Tarantulas that keep tiny frogs as pets. But what about humans? We cooperate with the microbes in our gut microbiome that help us digest, and we domesticate animals, plants, and even microbes like yeast to better serve our needs. Many organisms that are now domestic probably started out as mutualistic relationships, like dogs and cats, which are said to have effectively “domesticated themselves”. But can you think of any examples of symbiotic relationships we share with animals that are still wild?

There are really only two well-documented examples of human-wild animal symbiosis I’ve been able to find. One is the relationship between dolphins and fishermen in Brazil and Myanmar, in which a pod of dolphins will herd a school of fish toward fishermen who stand in the water, waiting with their nets. This setup doesn’t require goodwill between species to be beneficial to both: fish that don’t make it into the nets are easier for the dolphins to catch than without the humans’ involvement. However, the tradition seems to have begun only recently, only going back around 140 years in Brazil. Since dolphins are incredibly smart, it’s probable that additional populations of humans and dolphins have employed similar strategies in the deeper past. But the short history and the clear intentionality of this activity indicate that it didn’t come about through coevolution, but through the insights of clever individuals, more like a technology than a culture.

The other well-researched example is the relationship between honeyguides, a type of African bird related to woodpeckers, and human honey-hunters. As you’d expect from their name, honeyguides intentionally guide humans to bee nests containing honey, and then eat the grubs and wax left behind after the honey is extracted and the bees dealt with. Unlike the dolphin-fisherman partnership, this relationship goes back much further, possibly to our earliest hominin ancestors, and is more cultural than technological; that is, the humans and the birds both know what to do but don’t exactly know why it works. (For a deeper dive on what cultural evolution means, check out this Scott Alexander blog post.)

The other example that’s commonly brought up but is in fact fairly poorly researched is the relationship between ravens and human hunters in high latitudes. While ravens have a worldwide distribution, they have a disproportionate importance in the mythologies of northern peoples. This is probably because of their role in guiding hunters to prey in environments where prey is easy to spot from the air but patchily distributed. However, as far as I could find, no one’s really recorded any solid scientific observations showing that this relationship is significant (that is, that humans and ravens both obtain more calories through working together than they do working separately). It probably is, or at least was, but unlike the honey-hunters of eastern Africa, who still make their living through symbiosis with these birds, the raven-people no longer get their nutrition from the tundra, instead creating economic value in other ways and importing calories from places where they’re cheaper to produce.

In this post, I’ll go over how these relationships work and how they evolved, as well as other human-bird relationships that aren’t coevolved but I thought were interesting.

Wild birds

Honeyguides

There are a few species of bird commonly called honeyguides, but only one that actually engages in guiding behavior, the Greater Honeyguide. Its scientific name is literally Indicator indicator. Its job is clearly its claim to fame.

The area in which honeyguide-following is practiced spans modern-day Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique. Not coincidentally, this is also the “Cradle of Humankind”, the place in the world in which hominins have existed for the longest time. It’s one of the few places hard-coded relationships with the local fauna have had time to evolve. This area of the world is also very favorable to bees for some reason, with many species of small stingless bee, as well as the regular ol’ stinging honeybee, Apis mellifera, coexisting. Honeybees are the dominant honey-producing species in open, grassy habitats, while the small stingless bees are more common in the forest. And honeybees produce way more honey. This has important evolutionary implications we’ll get to later.

In the modern incarnation of the relationship, either party, human or bird, can solicit a honey-hunting session, by sighting the other and making a specific noise. The two tribes whose interactions with honeyguides have been rigorously documented, the Hadza of Tanzania and the Yao of Mozambique, use different calls for initiating honey-hunting, with the Hadza whistling melodiously and the Yao saying “brr-hm”. But the honeyguides of each area know the local passphrase and respond exclusively to it. [1]

After the hunt starts, the honeyguide will fly from perch to perch a few feet at a time, waiting for the honey-hunter to catch up. The whole time, it’s well within shooting distance if the hunter were to get out his bow. The Hadza are known to hunt birds of similar size to honeyguides. But honeyguides know their privileged status, and aren’t afraid. [2] Sometimes they get really close with their human partners:

Eventually, the honeyguide will stop near an Apis mellifera hive. The birds never guide to the small stingless bees for some reason that’s not well understood. Maybe the stinging beehives are easier for them to detect. Or maybe they prefer stinging bee hives because they’re bigger prizes that produce more and larger larvae and wax. Maybe they don’t recognize the small stingless bee nests as containing honey. Or maybe they just want to see the human get stung for some reason. In this part of the world, honeybee hives are usually super high up in baobab trees, probably to discourage humans from raiding them. Falling from heights is a major cause of death among honey-hunting peoples.

The honey-hunter uses smoke to sedate the bees, then cuts open the tree and breaks apart the beehive, getting the crap stung out of them in the process. He–only the men of these cultures are honeyguide followers, probably because it’s so dangerous; women who stumble upon a small stingless beehive will collect honey from it though–collects the honey, walls the tree hole back off to encourage the bees to return, and then proceeds to bury or burn as much of the leftover wax and grubs as possible, to minimize the reward for the honeyguide. When asked, they say they’re trying to keep the bird hungry so it will be more likely to guide again. “Wait, what?” you ask. “I thought this was mutualism!” Well, a honeyguide only weighs fifty grams, so even after the human has done his best to vandalize the remains of the hive, there are plenty of calories remaining to feed the one bird. The evolutionary purpose of destroying the hive is more likely to prevent other honeyguides from mooching, which does incentivize birds in general to want to guide, just not in the way the humans consciously expect. This type of relationship might better be called “manipulative mutualism”. [2]

In honeyguide-following societies, over fifteen percent of their total yearly calories comes from honey. That’s over a quarter cup of honey per person per day! And while some of this honey comes from chancing upon a beehive without the help of a bird, close to seventy percent of the honey haul comes specifically from honeyguide-led expeditions.

There have been reports of honeyguides also guiding honey badgers and baboons to beehives, but those appear to be apocryphal.

How do the honeyguides learn how to guide? How do they learn the specific human vocalization that means “show me the honey”? Honeyguides are brood parasites, which means they lay their eggs in other birds’ nests and don’t engage in any parental care. After fledging, the juveniles don’t immediately start their guiding careers. Instead, they sport a yellow “vest” of feathers that basically means “student driver”, and simply observe the behavior of the adults. By the time they lose their vests, they’ve figured out the procedure. The Yao people have two different words for the yellow-vested juveniles and the adults, and believe them to be two different species because their behavior is so different. [1]

How did this relationship come about? Molecular evidence suggests that the Greater Honeyguide arose at about the same time as our earliest hominin ancestors, between three and four million years ago, coinciding also with the spread of grasslands in the area. The grasslands encouraged tree-dwelling apes to spend more time foraging on the ground and eventually become bipedal and hairless, and they also caused honeybees to become more dominant and productive there. The hominins would have found beehives an excellent source of calories, and opened them to access the honey. But before Homo erectus tamed fire about a million years ago, earlier hominins would probably have been forced to abandon the hive before depleting it completely due to the bees’ defense, leaving a lot of nutrition laying around for other scavengers to exploit. The ancestors of honeyguides were probably one of these, following hominins around to pick up their scraps.

After our ancestors tamed fire, the payoff per hive for the birds would have substantially decreased. Each bird would have needed to be one of the first on the scene in order to eat their fill. A selective pressure was thus put on the birds to be better at predicting where beehives freshly opened by hominins might appear. The best way to predict such a thing was to engineer it, so the relationship transitioned from commensalism, in which the birds benefitted and the apes didn’t care, to mutualism. [2]

As our ancestors got smarter, they tried out different ways to improve on the relationship, probably including rewarding the honeyguide by leaving out a choice piece of honey-soaked comb, or withholding as much of the reward as possible “to keep the bird hungry”. Over thousands of years, the cultures that restricted the reward were more successful, so this behavior was perpetuated, even though its practitioners don’t know exactly why it’s useful.

Ravens

Common Ravens, Corvus corax, the world’s most oversized songbird, are found across the entire Northern Hemisphere in a wide variety of different biomes. They can subsist on almost anything, with different populations feeding mostly on grains, bugs, garbage, other birds’ eggs and young, roadkill, birds and small mammals they hunt, or large carcasses taken down by big mammalian predators. It’s that last item that provides the context needed for another instance of human-bird symbiosis. In the snowy taiga of North America and Europe, everything on that list is in short supply, except the meat of large herbivores killed by wolves, grizzlies, polar bears, and humans. (And their scat; as raven researcher Bernd Heinrich says in his book Mind of the Raven, “If they cannot intercept enough food at the front end of the dog, they get it eventually at the other end.” [3]) For thousands of years, ravens in snowy climates have made a living by following apex predators around and then consuming whatever is left behind.

However, similarly to the honeyguides, individual ravens can do better for themselves if they can engineer a hunt to happen and then be the first one on the scene. From their literal bird’s eye view, they’re able to spot herds of herbivores and packs of wolves on the open tundra from a great distance, and then signal the latter to follow them to the former. The signal is a single wing dip that tilts the bird to one side in the air, after which it rights itself and says “glug-glug-glug”. This is common knowledge among Inuits in Canada, but it has not been scientifically verified.

Also similarly to honeyguides, there’s another selective pressure on being good guides: ravens, not having hooked beaks like birds of prey, can’t open carcasses on their own, as honeyguides can’t access hives occupied by bees without help. Ravens require a mammal or eagle to come and flay the skin before they can feed. Therefore, if they know the location of an already dead animal, they can only get something out of it if they can find someone with the correct tools for the job.

Ravens have a natural affinity for dogs and wolves, and have been observed playing with both adult wolves and pups in Yellowstone. Wolf pups are smaller than ravens, so it’s concievable that the pups’ parents might consider ravens a threat and drive them off. But the wolves, too, seem to have a natural tolerance for the birds and don’t mind having them around. In both species, this tolerance seems to be innate rather than learned, lending support to the theory that their cooperation is coevolved.

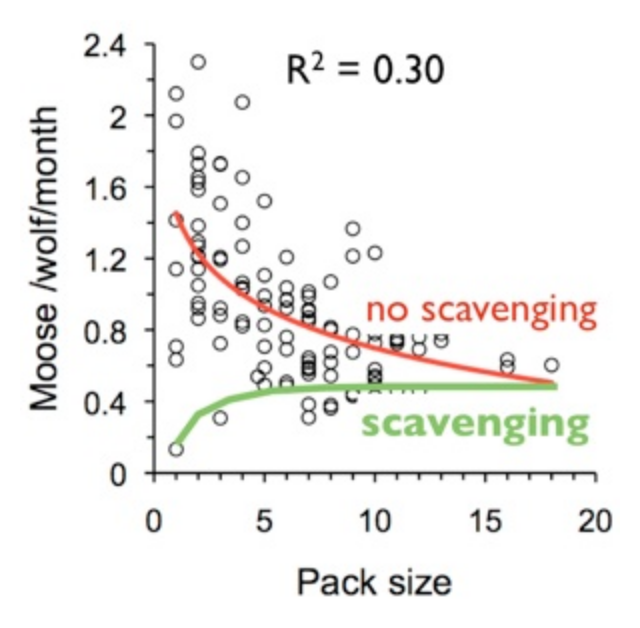

While ravens and wolves mutually benefit from their guiding interactions (wolves also get the perk of extra pairs of eyes scanning for danger while they feed), they are also in competition over the meat, with hundreds of ravens sometimes flocking to a single kill site and driving the wolves off after the carcass is opened. This is a big reason that wolves live in as large of packs as they do. In the absence of scavenging, the optimal number of wolves required to take down a moose would be two, to balance kill success rate with amount of meat available per wolf. But due to intense pressure from waiting ravens, wolves need to be able to, well, wolf down as much of the carcass as possible as fast as they can, to keep the spoils within the family. [4]

A strange side effect of tundra ravens’ total dependence on large carnivores for food is their innate fear of unoccupied food piles. When Bernd Heinrich stumbled upon the fresh carcass of an elk in Yellowstone who’d died of wolf-related injuries long after escaping and tore it open to allow his beloved ravens to access it, no one took him up on the offer. When elk hunters leave huge steaming piles of guts all over the ground, ravens won’t touch them. Wolves will, but since they like to feed as a pack, they’ll go to town on a single gut pile, and then the ravens will descend and fight over that same pile even when plenty of identical piles are uncontested. This makes rehabilitating tundra ravens in captivity difficult; to get them to eat, you or your dog needs to be actively eating the raw meat to make it look safe and enticing. [3]

Okay, but what does all this talk of wolves have to do with humans? Well, since ravens are quite smart, their behavior is fairly flexible. They associate with grizzly bears, polar bears, foxes, and eagles for the same reason as they do with wolves, but far less frequently, probably because those animals are both less successful at hunting the kind of prey ravens want, and less likely to follow a social cue from a raven. Humans are the only other tundra predator rivaling wolves in big game hunting prowess and social intelligence, and therefore make a good substitute. Due to this relationship, tundra peoples like Vikings, Scots, Sami, and Inuit revere ravens and consider them good omens, or even gods. However, it doesn’t seem like we share the same level of coevolved connection with ravens as wolves do. I’m not sure why that is, but my hypothesis is that wolves and ravens had been living in the far north of the Old World since before humans had spread that far, and therefore had more time to influence each other’s biology.

Trained birds

Cormorants

Everyone’s heard of falconry. But have you heard of cormorant fishing?

Cormorants are black, duck-sized waterbirds in the booby and frigatebird family Sulidae. They’re quite heavily built, prioritizing underwater maneuverability over flying ability, and sit low in the water when they swim at the surface, with just their heads sticking out. (See my previous post for photos.) They chase after fish in the water, which they grab using their hooked bills. Different species of cormorants can be found all over the world.

In modern China and Japan, and historically in Peru and Greece, wild-caught cormorants have been trained by humans to catch ayu (an approximately foot-long freshwater schooling fish known for the sweet, cucumber-like flavor of its flesh) while attached to a leash. They wear strings around their necks that prevent them from swallowing large fish, which they regurgitate for the fishermen. It’s unknown how long this has been practiced, but the first known mention of it in a historic document comes from 636 CE.

Each fisherman controls up to a dozen cormorants at once, and they work every night from May to October in boats with a big flaming lantern on the front, whose light attracts the fish. Since the time of Nobunaga (14th century), this has been a big tourist attraction, which is the main reason the tradition persists. While undoubtedly cool, cormorant fishing is pretty impractical. Ayu can be caught using other methods, such as fly fishing or using traps or decoys, through which a hundred percent of the fish can be consumed by humans, rather than the smaller ones being swallowed by the birds. Cormorants are fairly large and need to consume around 750 grams of fish (1.7 pounds) every day. Furthermore, it takes between six months and three years to fully train a new bird, during which they’re eating fish without catching any.

Birds of Prey

Falconry, or hunting small prey using a trained falcon, hawk, eagle, or owl, is an ancient practice that started in Mesopotamia around 4000 years ago. Since then, it has maintained cultural importance in the Arab world (the UAE spends $27 million annually on falcon conservation and rehabilitiation), and was introduced to Europe around 400 CE. Traditionally, Saker Falcons were the bird of choice in Arabia, and Eurasian Goshawks in Europe (with goshawk-using falconers known as austringers), but today other species like the Red-Tailed Hawk, Harris’s Hawk, and Peregrine Falcon are more common.

About a thousand years ago, people in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan began using Golden Eagles in falconry, to hunt foxes for their pelts from horseback out in the wide-open steppe. Eagles are enormous, hard to train, and only very effective in open environments. But they’re pretty cool. When the Soviet Union conquered Kazakhstan in the 1930s, eagle hunting was banned, and many traditional eagle hunters fled to the province of Bayan-Ölgii in Mongolia. Today, a few eagle hunters have returned to the independent Kazakhstan, but most remain in Mongolia. While most birds used for falconry weigh between one and five pounds, a Golden Eagle female can reach seven kilograms (15 pounds).

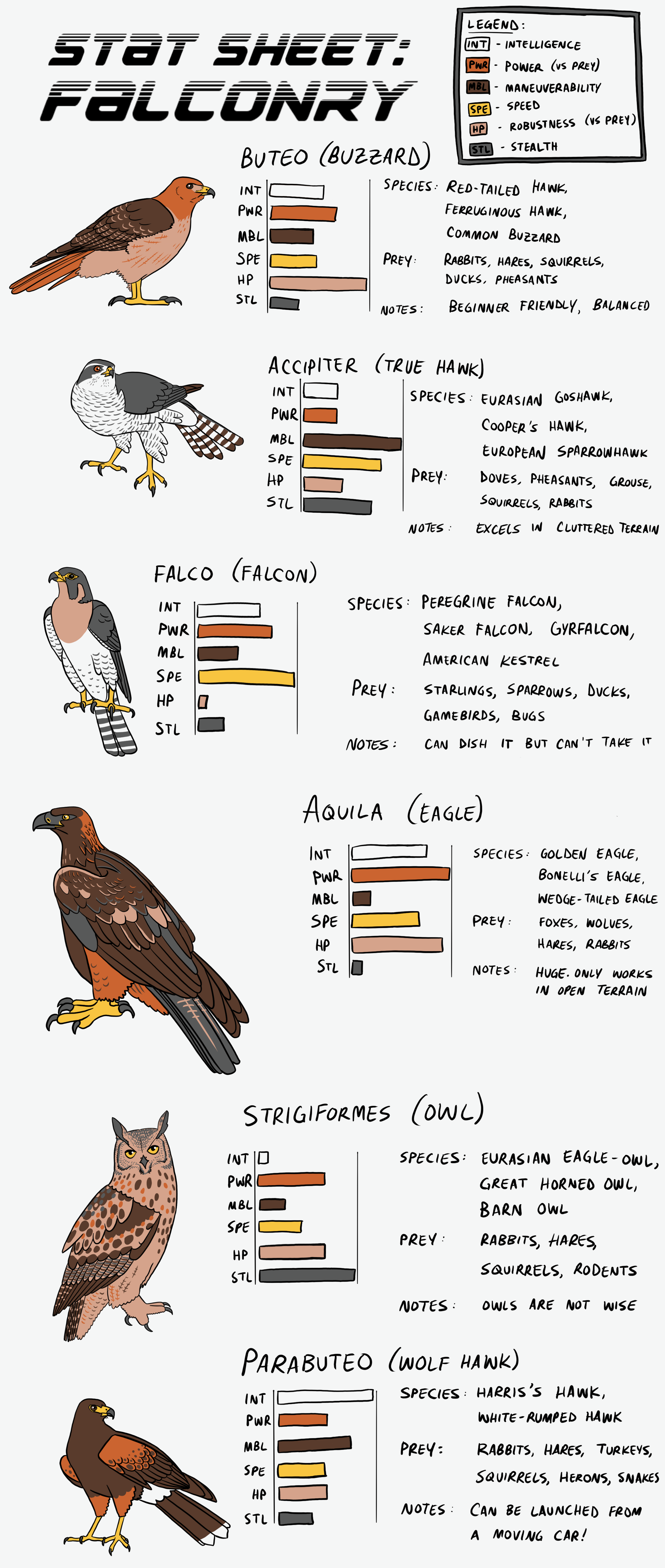

I’m going to take a page out of TierZoo’s playbook and assign stats to the main classes of birds used in falconry, as if they’re Pokémon, grading them on intelligence, power, maneuverability, speed, robustness, and stealth. [5] [6] I posted a preliminary version of this chart to Reddit, and the people at r/Falconry suggested tweaks to the stats and the species lists. Now I’m fairly confident that this accurately reflects people’s sentiments about falconry birds, at least, if not the actual birds’ abilities.

And that’s all I have to say about falconry.

Tamed birds

Canaries

I saw my first wild canary in Madeira, Portugal in October. The Canary Islands for which the bird is named lie a bit south of Madeira but share a lot of the same fauna. The islands’ name comes from Latin for “Isle of Dogs” (no relation to the Wes Anderson film), in reference to the many dog-like monk seals that lived there. What a long chain of etymology: monk seals to dogs to islands to birds.

In the 1600s, Spanish sailors brought wild birds to Europe and sold them as pets, where they were popular due to their attractive songs. Over the past few centuries, they have been selectively bred to express different colors, shapes, and songs, creating a subspecies of domestic canary that comes in many breeds. Like dogs, cats, and horses, people compete them in canary shows.

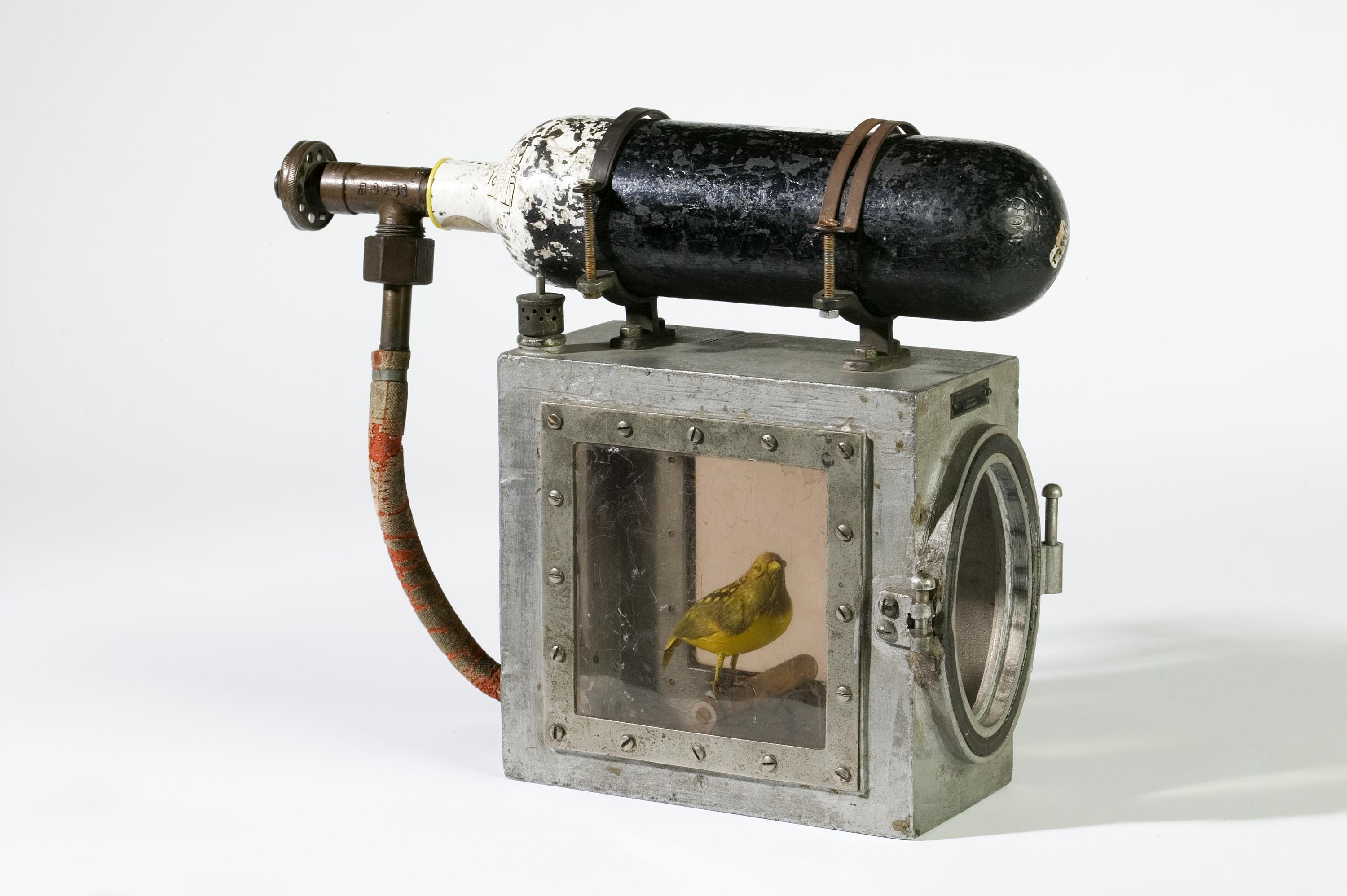

In 1896, the very colorful scientist John Scott Haldane proposed using canaries to detect whitedamp, or toxic gases like carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide, that couldn’t be detected by a simple flame test the way firedamp (flammable substances like methane and coal dust) and blackdamp (an anoxic mixture of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor) could. JS Haldane was an avid self-experimentalist whose family motto was simply “Suffer.” He created the first gas masks used in World War I that replaced the urine-soaked rags soldiers used to protect their lungs at the time. He also figured out what caused the bends (decompression sickness that happens when divers surface too quickly), and created a reference table for safe decompression that’s still used today.

Coal miners, not having a lot of light in their lives, loved their little yellow companions. Canaries in coal mines were kept in little contraptions that could seal airtight when the bird fell off the perch and activate a little oxygen tank to resuscitate it.

These birds and similar boxes were used for the better part of a century, only phased out in 1986, 89 years after Haldane introduced them, once electronic gas detectors became good enough. Miners generally didn’t like the newfangled detectors and were sad about losing their companions, but it was probably for the best, animal-cruelty wise.

Parrots

Parrots have been kept as pets for thousands of years, but the international parrot trade only really kicked off during the Age of Exploration/Colonization, when people in Europe and America would pay lots of money for enormous, colorful, living status symbols. Today, many parrot species are threatened with extinction due to their high demand as pets. Since parrots are so long-lived and intelligent, they often don’t breed well in captivity. Thus, poachers are incentivized to gather as many birds as possible from the wild and smuggle them across continents, a journey most don’t survive. This practice, still alive and well today, was first codified on the high seas, which is where the iconic image of a peg-legged pirate with a shoulder parrot comes from. The Ur-example is the pirate Long John Silver in Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 novel Treasure Island, who has a Blue-and-yellow Macaw named Captain Flint that sits on his shoulder and says piratey things like “Pieces of eight” and “Stand by to go about”.

While real-life pirates definitely smuggled and sold parrots, they probably didn’t keep them long-term as pets. Parrots have a lot of needs, and as any parront will know, are prone to dying suddenly from the slightest provocation. Also, when given freedom to fly around, they often get instantly lost and cannot or will not return. Pirates letting their cargo out of their cages would have been taking a lot of unnecessary monetary risk just for a little fun. But it probably happened at least once!

Domestic birds

Society Finches

While canaries and certain parrot species like cockatiels can be described as “semi-domestic” (my term)–that is, they have marked physiological differences from their wild counterparts, but don’t exhibit natural tameness and easily revert to a feral lifestyle–some birds are undoubtedly fully domesticated. The obvious example is the chicken. But have you heard of the Society Finch?

Also known as the Bengali Finch, these birds were created in the 1600s or so in Japan and China by hybridizing a bunch of different species of munia and mannikin, with the White-backed Munia providing the most genetic material. As a result, nothing like the Society Finch exists in the wild. They were bred for socialability, ease of care, and various colors, and are commonly used as foster parents for other types of finches, as a male-male couple will readily adopt and care for other birds’ eggs. They are so enthusiastic about this that Society Finch couples must be kept in individual cages, or else if an egg is introduced, all the birds will crowd into the one nest to try to incubate, increasing the risk of damaging the egg or fights breaking out.

Another interesting aspect of Society Finches is their song, which is much more complex than that of any of their ancestor species. They weren’t explicitly bred for their singing abilities, so it’s not fully understood if complex singing abilities are a side-effect of domestication the way curly tails and floppy ears are in dogs and pigs, or if domestic birds are simply less stressed than their wild counterparts and therefore have more motivation and energy to devote to fun pastimes like singing. Preliminary evidence favors the latter hypothesis.

Chickens

Last but not least, there’s the humble, yet epoch-defining chicken. There are over 33 billion chickens on Earth right now, up from only eleven billion in 1990. The reason is the increase in demand for “broilers”, or chickens raised specifically for meat, relative to egg-layers. However, due to the short lifespan of broilers in factory farms–only 42 days–over 69 billion chickens blink in and out of existence each year. As a reminder, there are only eight billion humans in the world. For a vast majority of the chicken’s history, its primary purpose was to lay eggs, and the bird could expect to be slaughtered only upon reaching menopause. It’s only the rising global standard of living, with more people eating more meat more often, that has changed the chicken’s job description in recent years.

How did this particular species of bird get into this absurd situation? The chicken was domesticated from the Red Junglefowl around 8000 years ago in Southeast Asia. (That’s a long time ago, but dogs, sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle are thought to have been domesticated close to 10,000 years ago. Chickens were probably the first domestic bird though.) Adult chickens still look a lot like their wild type Red Junglefowl counterparts, but the chicks look quite different: junglefowl chicks are much more cryptically colored, and show more obvious gender differences. The classic yellow chicks we’re familiar with today were probably selected specifically to be highly visible, so farmers could more easily keep track of them. And the reason domestic chicks exhibit far less sexual dimorphism is probably their evolutionary counter-attack: since roosters are badly behaved and don’t lay eggs, farmers usually cull them as chicks, keeping only the females, except for the very few roosters needed to keep the species alive. But an effeminate rooster has a chance at slipping through the cracks and passing on his henlike genes. Nowadays, chicks’ gender can’t be discerned except by professional chicken sexers. Yes, that is a real job title.

While many birds produce an egg a day when in the process of building up a clutch, junglefowl (there are other colors of junglefowl that have contributed some amount of genetic inheritance to modern chickens, such as Green and Grey Junglefowl) have adapted to take advantage of the seasonal food supply of the periodic cicada. When food is plentiful, they can lay multiple clutches per year, and if eggs are removed from the clutch, they can lay replacements. These traits made them perfect for enterprising humans to take advantage of. Over the millennia, chickens have been selectively bred to be more and more efficient egg machines, requiring less food, producing bigger eggs, and inching ever closer to the ideal of an egg every single day.

References

[1] Spottiswoode, C. N., Begg, K. S., & Begg, C. M. (2016, July 22). Reciprocal signaling in honeyguide-human mutualism. Science, 353(6297), 387–389. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf4885

[2] Wood, B. M., Pontzer, H., Raichlen, D. A., & Marlowe, F. W. (2014, November). Mutualism and manipulation in Hadza–honeyguide interactions. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(6), 540–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.07.007

[3] Heinrich, B. (2007, May 29). Mind of the Raven. Harper Perennial. http://books.google.ie/books?id=abislwEACAAJ&dq=Mind+of+the+Raven&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api

[4] Ravens Give Wolves a Reason to Live in Packs. The Wolves and Moose of Isle Royale. (n.d.). https://isleroyalewolf.org/node/43

[5] Macdonald, H. (2014, July 31). H is for Hawk. Random House. http://books.google.ie/books?id=B09UAwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=H+is+for+Hawk&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api

[6] Windrow, M. (2014, February 27). The Owl Who Liked Sitting on Caesar. Random House. http://books.google.ie/books?id=bcrHAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA66&dq=The+owl+who+liked+sitting+on+Caesar&hl=&cd=2&source=gbs_api

Image Credits

Honeyguide juvenile Wolves and ravens Raven graph Cormorant fishing Eagle hunter John Scott Haldane Canary device Society finch Red Junglefowl chick