The last time I discussed pregnancy on the blog, I focused almost entirely on various strange phenomena that occur in non-human animals who give live birth. This time, I’m focusing on the way one phenomenon occurs in humans: “pregnancy brain”.

Many women in their second and third trimesters report feeling foggy, absent-minded, forgetful, and inarticulate. These are symptoms of a very real, very dramatic brain reorganization triggered by those raging pregnancy hormones. It should really be called second puberty, not just because of the suite of extreme and systematic physiological changes, but also because the brain development shares some striking parallels to what goes on in both male and female brains during adolescence. The main obvious observation is a large reduction in gray matter, or the wrinkly outside part of the brain. In this post, I’ll give you an overview of what the latest science has to say about this, and answer as many questions I had about it as I can. Does it result in cognitive impairment? Does it recover after pregnancy is over? Is it cumulative across multiple pregnancies? What’s the evolutionary purpose–something must be gained, right?

What’s happening, physically?

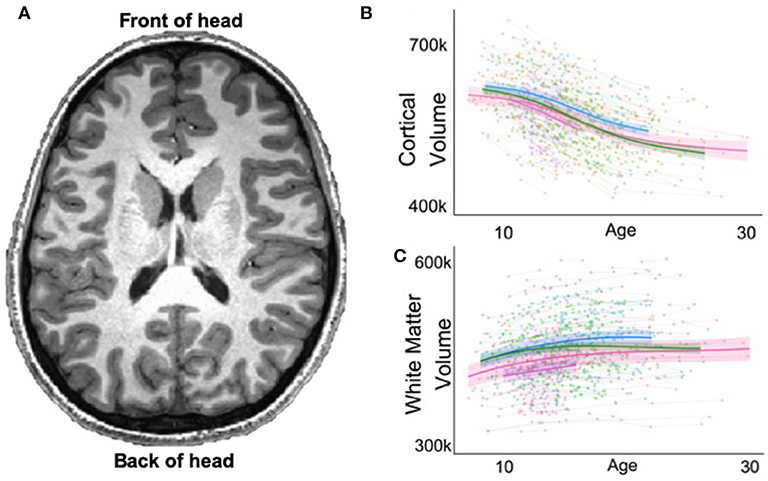

In adolescence, people lose around 17% of their gray matter over a period of about 15 years [1]. And though “losing 17% of your brain” sounds bad, this time period, from age 11 to 26, is associated with large increases in executive function (self-control), temporal discounting (ability to refuse a small, immediate reward in order to hold out for a larger, later one), and general computational skills (could you do the math you can now when you were 11?). The way the brain grows seems to be by overproducing neurons and synapses, and then pruning excess or redundant ones to improve speed and prioritize relevant connections.

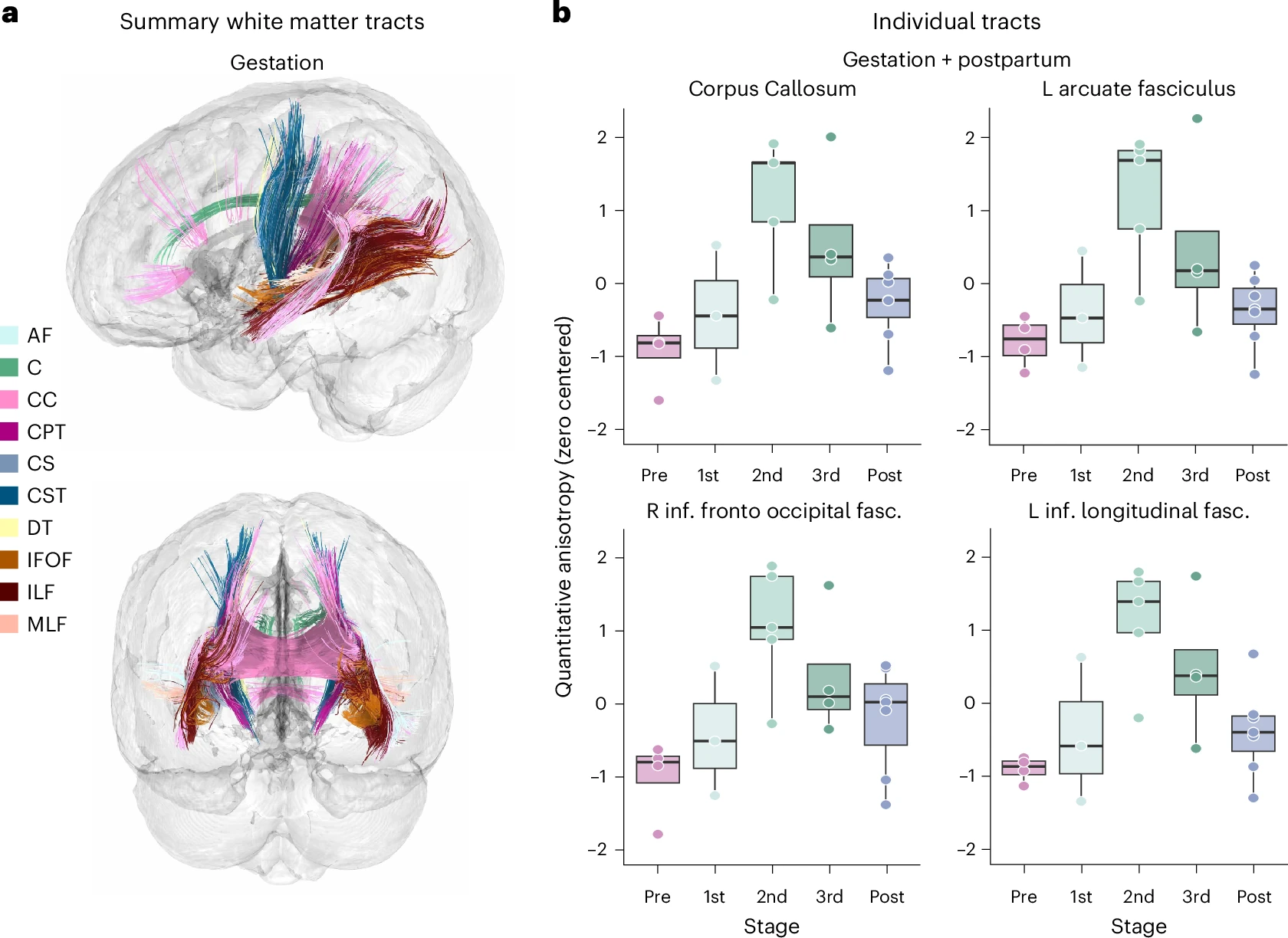

During puberty, though, the decrease in gray matter is offset by a corresponding gain in white matter in the same structure or network [2]. Gray matter is composed of neuronal cell bodies, while white matter, the layer located just below the gray matter in the brain, is made up of the long tails that stick off each neuron and connect to others. Myelin sheaths, or the fatty rings that wrap around the long portion of a neuron, which you may have heard of and which famously increase signal speed, are a component of white matter. In light of that, the increased cognitive capabilities associated with puberty make sense: the brain is getting faster and more streamlined.

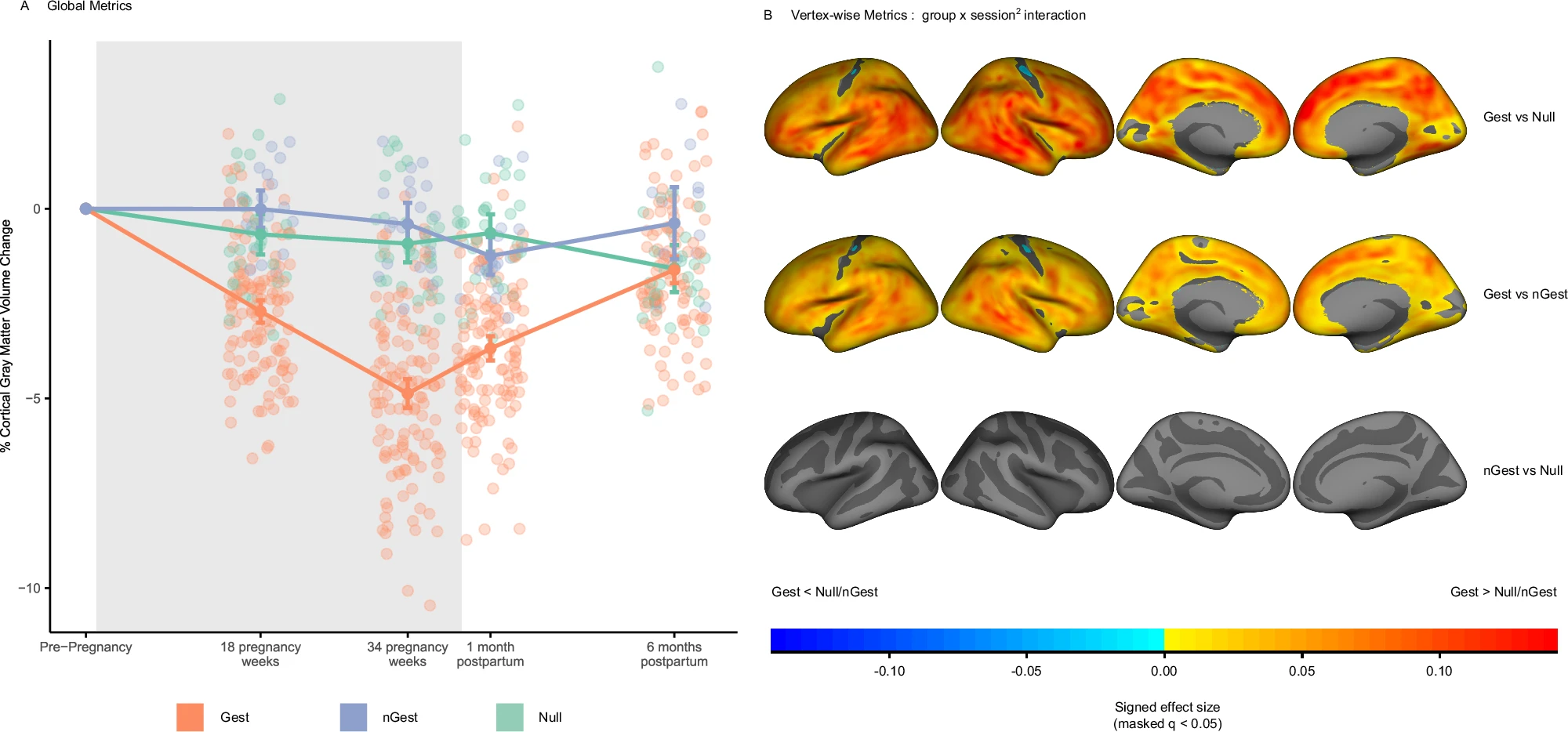

In contrast, women lose around 5% of their total gray matter from 80% of brain structures during pregnancy - sweeping changes, for sure, but around three times less in magnitude than what happens during normal maturation. But there’s no accompanying white matter increase. During pregnancy white matter does increase, peaking in the second trimester, but by the time birth rolls around, the white matter is back to pre-pregnancy baseline [3]. The reason for this transient change isn’t known, but it seems like it’s likely related to the way the brain goes about performing this pruning, since the mechanisms driving brain changes during adolescence and pregnancy are much the same [4]. But the upshot is, at the end of pregnancy women have less brain than before, while at the end of puberty adults have a different but comparably-sized brain.

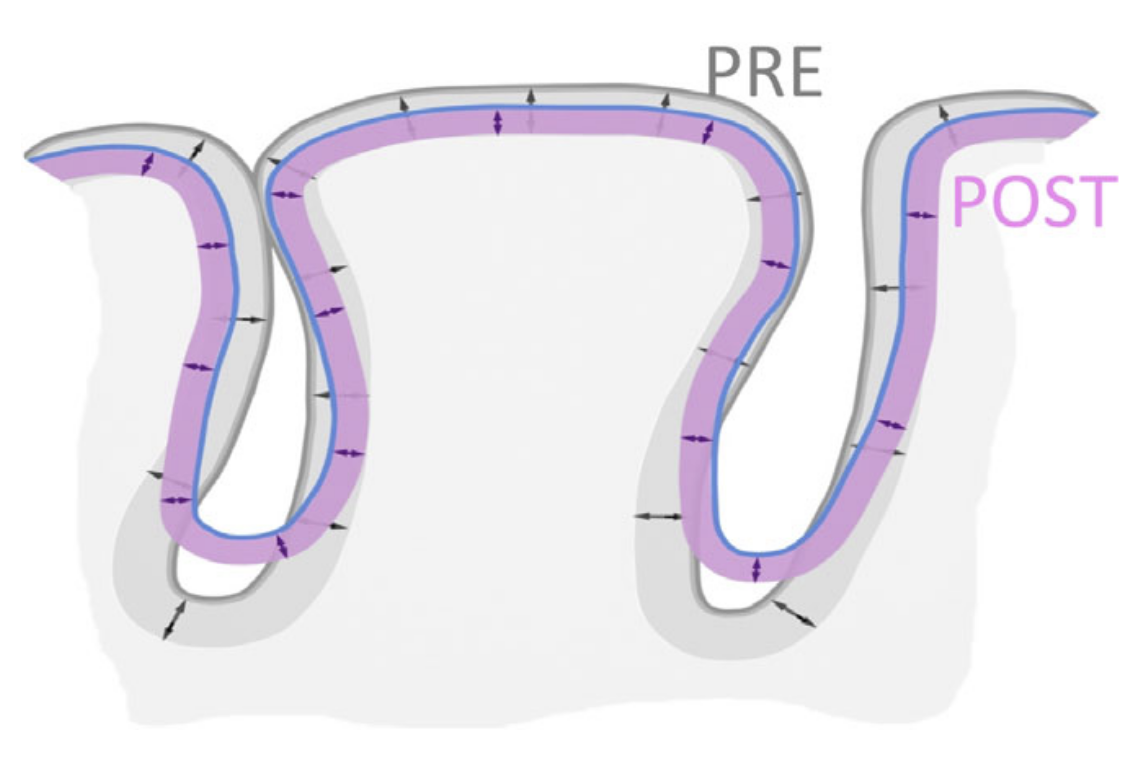

Physically, during both pregnancy and adolescence, the brain is flattening: the wrinkles get shallower, resulting in less gray matter without changing the overall space the brain takes up [4]. This makes sense–it’s not like your brain rattles around inside your skull more as you go through puberty.

It’s important to note that “changes in [gray matter] signal extracted from MRI images can reflect various processes, such as changes in the number of synapses, the number of glial cells, the number of neurons, dendritic structure, vasculature, blood volume and circulation, and myelination” [7]. Other factors can also include average cell body size and volume and pressure of cerebrospinal fluid [8]. That is, MRI is a pretty crude tool for measuring what’s actually going on inside a brain, because it can’t distinguish between any of these cases that all can lead to brain volume changes. As I’ve often said, medicine is in the Bronze Age compared to most sciences, and neuroscience is in the Stone Age. There is a lot that is not well understood.

Is this reduction associated with cognitive impairment?

Short answer: Yes. Pregnancy brain is real.

Long answer: Some cognitive functions are impaired, some are unaffected, and a few are enhanced. Verbal recall, or finding the word you’re looking for in real time, takes the biggest hit, with a p<0.001 confidence level difference between non-pregnant women and pregnant women [5]. The test that the researchers employed in that study to test verbal recall is pretty hilariously basic. “Naming objects and fingers: Participants were asked to name twelve real objects that were shown to them and state the name of each of the fingers of the dominant hand. Scoring: each object or finger correctly named was graded one point, to a maximum total of 17 points.” The median score in both groups was 17/17, but only pregnant women couldn’t name some of the objects or fingers and lost points. Other studies have backed up these results, such as when a “trend was observed for a reduction in the number of correct responses on the verbal word list learning task” [7].

Other areas of decreased ability include working memory, free recall, subjective memory, and processing speed. However, that doesn’t include reaction time, as there was “no difference in reaction time between pregnant and non-pregnant women in a snakes in the grass pop-out task, and further found that pregnant women were more accurate than non-pregnant women at detecting threatening stimuli (spiders) amongst nonthreatening stimuli (flowers and butterflies)” [6].

Areas of increased ability during pregnancy include recognition, especially of faces, especially same-race male faces (the most likely to attack you in the environment of evolutionary adaptiveness?) [10]; “encoding of emotions denoting threat (anger, fear, disgust) and sadness, [which] suggest that there may be a cognitive bias towards threatening stimuli in late pregnancy” [11], and “increased vigilance, which serves a protective function. Approximately 20% of the pregnant women in the study reported driving more carefully since becoming pregnant…Eight of 17 non-pregnant women were involved in a virtual collision on at least one trial, but only 1 of 13 pregnant women was involved in a virtual collision” [6]. All of these changes make sense from an evolutionary standpoint. Pregnancy is a huge investment of resources, and it’s best to avoid things (strange men, disease, dangerous situations) that could cause a miscarriage and waste all your effort so far.

Furthermore, “stress response is dampened in pregnancy; blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol reactivity to a variety of stressors are mitigated during pregnancy…women in later pregnancy perceived major life events as less stressful than women in earlier pregnancy. For example, women who experienced a major earthquake in late pregnancy reported the event as less stressful than women who experienced the earthquake in early pregnancy” [6]. This also makes perfect sense: stress is generally bad for you. Being less stressed puts less…stress…on the baby’s fragile systems. Stress dampening is especially interesting when connected to the aforementioned increased ability to detect threatening emotions in others, because in non-pregnant people, higher sensitivity to others’ emotions is correlated with higher anxiety [6]. Pregnant women get the increased empathy without the downside.

One thing that irked me about this study, which was a review of other studies on the topic (which is why I’m citing it so much), was how they criticized how the literature tended to focus on the decline in memory performance associated with pregnancy, while not investigating potential other areas that may not be affected or even show improvements if anyone thought to ask those questions. “We suggest that the narrow focus on memory decline may be eclipsing potential advantages shared by women…A criticism that may be directed at much of the current research investigating cognition in pregnancy and the postpartum period is that the tasks employed are often abstracted verbal tasks that are devoid of ecological validity and relevance to everyday life” [6]. This is a valid point–you can only learn about the things you think of to test, and there are almost certainly tasks whose performance is affected by pregnancy that scientists just haven’t thought to test. However, the reason for the focus on memory lapses is because this is the most commonly reported symptom that pregnant women notice about themselves. Furthermore, calling the memory tests “devoid of…relevance to everyday life” is pretty dismissive. Sure, these tasks aren’t things you’d do as a cavewoman in the environment of evolutionary adaptiveness. But we don’t live that way anymore. Many women go to work, where they’re engaged in cognitively demanding tasks every day, the outcomes of which are important to their livelihoods. Dismissing these cognitive impairments as not representative of daily life is just that: dismissive.

There are also myths that mothers are better at picking out their own infants’ cries from others’, and that mothers are more accurate at decoding what the baby is crying about than fathers. But this has been found not to be true. The only variable that matters in the ability of the parent to recognize and understand their baby is how much time they’ve spent with the baby. In most households, the mom spends more time with the baby, hence the perceived gender difference. But after correcting for that, men and women perform about the same [13].

This is all during pregnancy. What about after?

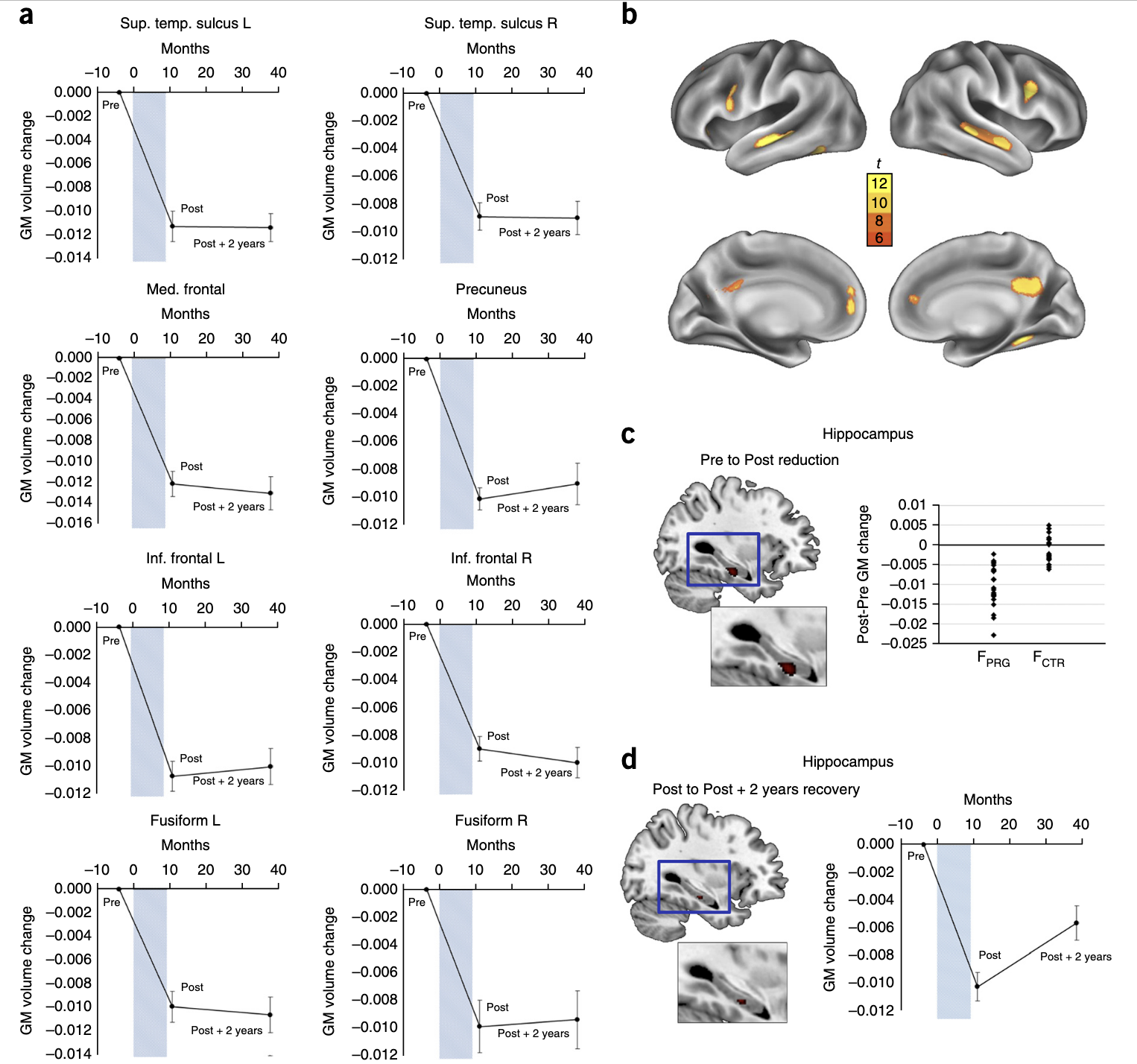

The good news is, there’s a large rebound in gray matter volume immediately after pregnancy–within the first 4-10 weeks. That’s a lot of brain growth in a short time! However, it doesn’t all come back, leaving the mother with an average of 2.5% less gray matter than pre-pregnancy. And doesn’t come back the same way [8].

“We hypothesize that since the brain lies in a limited space and closed box, this prior shrinkage is required in order to prepare it for further development after parturition. The mother-baby bonding requires lots of adaptive changes in the postpartum mother’s brain, which are linked to areas concerned with social cognition, primarily in networks involved in motivation, somatosensory information and executive functions. These may be then mediated by experience-dependent plasticity during the postpartum period” [5]. In other words, there are a bunch of motherly instincts you need to download in order to succeed in child-rearing, but your existing brain doesn’t have the storage space. So you first have to delete some stuff in order to get the update.

As with adolescence, pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period are the times in a person’s life in which they’re at the highest risk of developing a psychological abnormality, like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression [4]. Large-scale brain reconfigurations are risky, as you’re destabilizing a very important and complicated system. This is what’s behind postpartum depression, anxiety, and psychosis (yes, that’s a thing): the growing pains of reinventing your brain. Or, in some rare cases, a software update that corrupts the system.

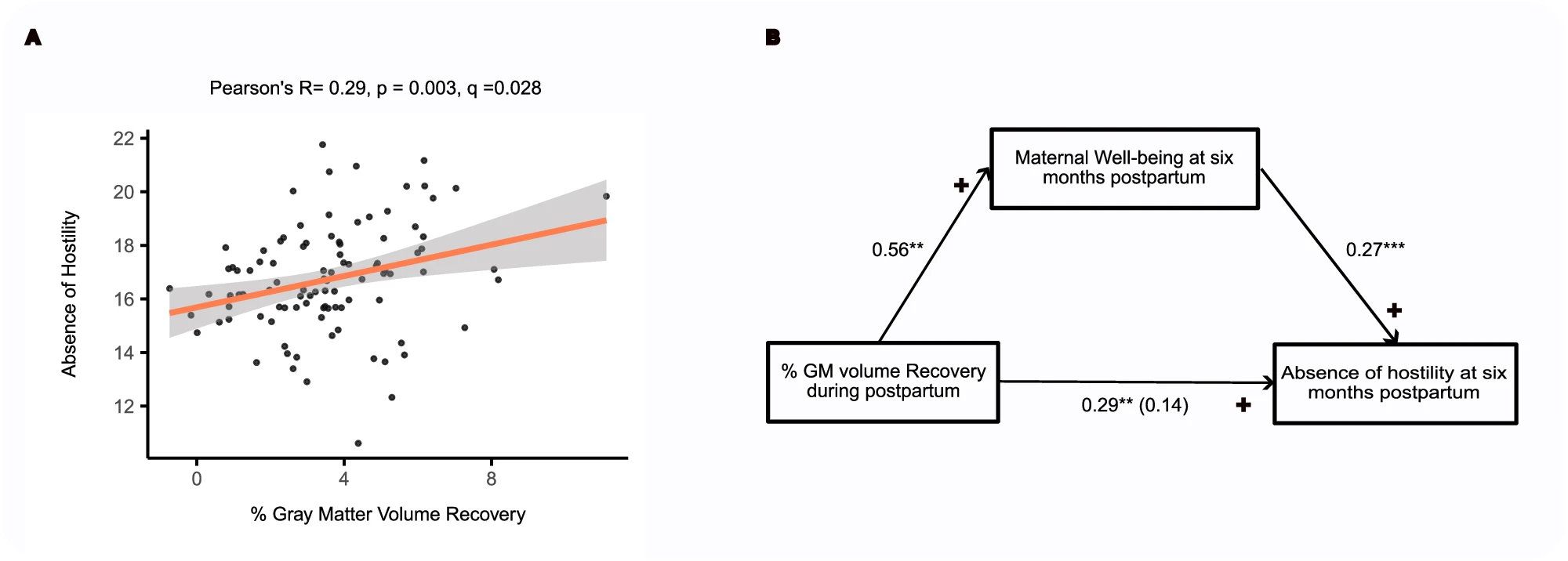

Some interesting predictive trends can be observed once the baby is out, since you can now show the woman pictures of her baby (and other babies, and other stuff) while she’s in the MRI scanner. “Several of the regions that showed the strongest neural activity in response to the women’s babies corresponded to regions that lost [gray matter] volume across pregnancy” [7]. And “increased gray matter volume in the midbrain including the hypothalamus, substantia nigra, and amygdala was associated with maternal positive perception of her baby” [9]. While at first it may seem counterintuitive that lost gray matter is associated with those brain structures that are needed to interact with your baby, it makes sense when coupled with the regrowth of gray matter after birth. Those were the areas in need of an update. And if the update doesn’t take so well–if you get the gray matter reduction but not as much recovery–it’s associated with more reported hostility toward the infant.

What causes the update not to take? While it would be interesting to know exactly what childrearing activities encourage brain growth, there are so many confounding variables across households that this is really hard to study. It would also be useful to know how the effects stack up across multiple pregnancies. I looked really hard for studies focusing on these questions, but didn’t find any. Future work!

Does it ever recover back to baseline?

No.

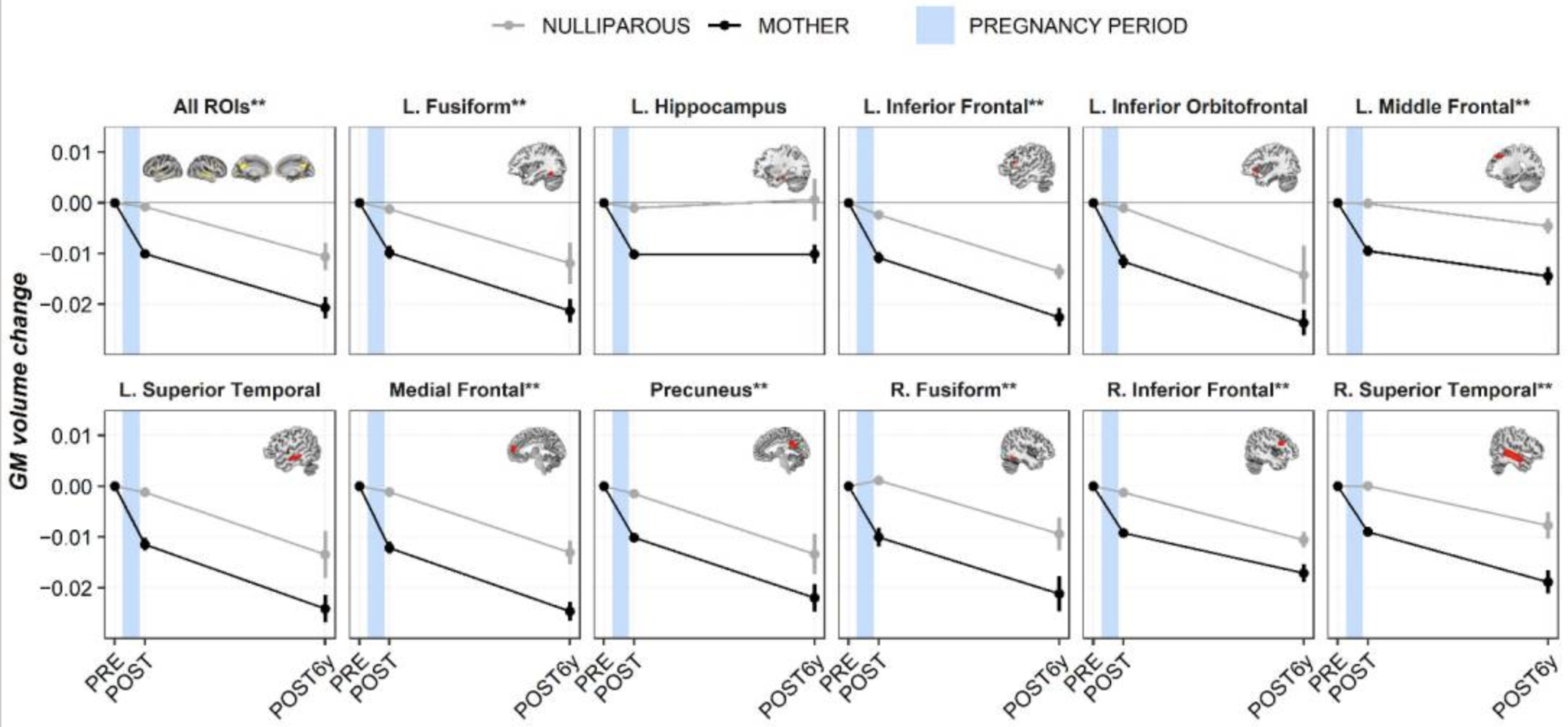

Even “at six years after parturition, it is still possible to accurately discriminate between mothers and nulliparous women” [12]. The transformation into a mother is a one-way trip. The structural changes to the brain that occur during a single pregnancy last a lifetime.

However…

There are silver linings. People who have kids are more resistant to the gray matter loss associated with natural aging than those who don’t. “Parity was associated with larger total gray matter volume later in life, a finding that persisted following adjustment for sociodemographic factors. The larger gray matter volume associated with parity appeared not to be driven by specific lobar brain regions, but rather was globally proportional across lobes” [14]. This applies to both men and women [15]! Not fair! Men don’t have to undergo a big brain shuffle, but still get the benefits of their wives shouldering that burden for them. In the six-year study, you can see how the controls (gray line) are also undergoing gray matter loss, just offset by the massive drop during pregnancy.

The fact that this affects both men and women indicates that the mechanism is completely unrelated to everything that happens in pregnancy, but rather is related to childrearing. We’d therefore predict that adoptive parents would enjoy the same benefits. There have been a few studies on the brain chemistry of adoptive parents and how it does become similar to that of birth parents given long enough exposure to the adopted child, but I don’t know of any studies on whether adoptive mothers’ brains undergo the same structural changes, nor of any examining adoptive parents’ brains later in life.

In addition to the benefit of hanging onto more of your brain for longer, parents always report more satisfaction with life and hopefulness about the future than non-parents [17]. This result is repeated again and again in polls–kids are good for your mental health.

Another weird note is that someone trained a machine learning model to assign an age to an MRI brain scan. It got quite good at accurately predicting people’s ages from snapshots of their brains. When applied to pregnant women, it was also accurate; but at 4-6 weeks after birth, it predicted that the mothers were on average five years younger than it thought they were before they gave birth [16]. Given AI models are black boxes, we don’t know what characteristics it’s picking up on. There’s definitely been some recent growth and reshuffling in those brains–is that what it’s seeing? Or is there some other property of young brains that postpartum women share?

Conclusion

In preparing for my own pregnancy, I read a lot of long-form books and scientific papers, trying to learn what I was in for. I think a short-form blog post would’ve been helpful to me, so I thought I’d write one to fill the gap. The pattern of brain loss and regrowth is easily observable, but still not well-understood. Most of the papers on this are quite recent, with the most recent published just this past January, so it appears that the scientific community is finally taking an interest in this phenomenon that impacts 85% of women at some point in their lives. Hopefully there will be more research soon addressing my out-standing questions… and more education generally about both “pregnancy brain” (gray matter loss) and “mommy brain” (brain rebuilding). I think it’s unacceptable that a vast majority of women go into pregnancy without understanding that they’re signing up for a complete identity overhaul. If one person reads this before pregnancy, I’ll have helped.

References

[1] Mills, K. L., & Anandakumar, J. (2020). The adolescent brain is literally awesome. Frontiers for Young Minds, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/frym.2020.00075

[2] Bray, S., Krongold, M., Cooper, C., & Lebel, C. (2015). Synergistic Effects of Age on Patterns of White and Gray Matter Volume across Childhood and Adolescence. eNeuro, 2(4), ENEURO.0003-15.2015. https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0003-15.2015

[3] Pritschet, L., Taylor, C.M., Cossio, D. et al. Neuroanatomical changes observed over the course of a human pregnancy. Nat Neurosci 27, 2253–2260 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01741-0

[4] Carmona, S., Martínez‐García, M., Paternina‐Die, M., Barba‐Müller, E., Wierenga, L. M., Alemán‐Gómez, Y., Pretus, C., Marcos‐Vidal, L., Beumala, L., Cortizo, R., Pozzobon, C., Picado, M., Lucco, F., García‐García, D., Soliva, J. C., Tobeña, A., Peper, J. S., Crone, E. A., Ballesteros, A., . . . Hoekzema, E. (2019). Pregnancy and adolescence entail similar neuroanatomical adaptations: A comparative analysis of cerebral morphometric changes. Human Brain Mapping, 40(7), 2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24513

[5] Barda, G., Mizrachi, Y., Borokchovich, I., Yair, L., Kertesz, D. P., & Dabby, R. (2021). The effect of pregnancy on maternal cognition. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91504-9

[6] Anderson, M. V., & Rutherford, M. D. (2012). Cognitive Reorganization during Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: An Evolutionary Perspective. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(4), 659–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491201000402

[7] Hoekzema, E., Barba-Müller, E., Pozzobon, C., Picado, M., Lucco, F., García-García, D., … Vilarroya, O. (2016). Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure. Nature Neuroscience, 20(2), 287–296. doi:10.1038/nn.4458

[8] Servin-Barthet, C., Martínez-García, M., Paternina-Die, M. et al. Pregnancy entails a U-shaped trajectory in human brain structure linked to hormones and maternal attachment. Nat Commun 16, 730 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55830-0

[9] Kim, P., Leckman, J. F., Mayes, L. C., Feldman, R., Wang, X., & Swain, J. E. (2010). The plasticity of human maternal brain: Longitudinal changes in brain anatomy during the early postpartum period. Behavioral Neuroscience, 124(5), 695–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020884

[10] Anderson, M. V., & Rutherford, M. (2011). Recognition of Novel Faces after Single Exposure is Enhanced during Pregnancy. Evolutionary Psychology, 9(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491100900107

[11] Pearson, R., Lightman, S., & Evans, J. (2009). Emotional sensitivity for motherhood: Late pregnancy is associated with enhanced accuracy to encode emotional faces. Hormones and Behavior, 56(5), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.09.013

[12] Martínez-García, M., Paternina-Die, M., Barba-Müller, E., De Blas, D. M., Beumala, L., Cortizo, R., Pozzobon, C., Marcos-Vidal, L., Fernández-Pena, A., Picado, M., Belmonte-Padilla, E., Massó-Rodriguez, A., Ballesteros, A., Desco, M., Vilarroya, Ó., Hoekzema, E., & Carmona, S. (2021). Do Pregnancy-Induced Brain Changes Reverse? The Brain of a Mother Six Years after Parturition. Brain Sciences, 11(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11020168

[13] Gustafsson, E., Levréro, F., Reby, D. et al. Fathers are just as good as mothers at recognizing the cries of their baby. Nat Commun 4, 1698 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2713

[14] Aleknaviciute, J., Evans, T. E., Aribas, E., De Vries, M. W., Steegers, E. a. P., Ikram, M. A., Tiemeier, H., Kavousi, M., Vernooij, M. W., & Kushner, S. A. (2022). Long-term association of pregnancy and maternal brain structure: the Rotterdam Study. European Journal of Epidemiology, 37(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00818-5

[15] Orchard, E. R., Ward, P. G. D., Sforazzini, F., Storey, E., Egan, G. F., & Jamadar, S. D. (2020). Relationship between parenthood and cortical thickness in late adulthood. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0236031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236031

[16] Luders, E., Gingnell, M., Poromaa, I. S., Engman, J., Kurth, F., & Gaser, C. (2018). Potential Brain Age Reversal after Pregnancy: Younger Brains at 4–6 Weeks Postpartum. Neuroscience, 386, 309–314. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.07.006

[17] Morning Consult. (2023). THE PUBLIC, PARENTS, AND K–12 EDUCATION. https://edchoice.morningconsultintelligence.com/assets/226853.pdf

[18] Luders, E., Kurth, F., Gingnell, M., Engman, J., Yong, E.-L., Poromaa, I. S., & Gaser, C. (2020). From Baby Brain to Mommy Brain: Widespread Gray Matter Gain After Giving Birth. Cortex. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2019.12.029