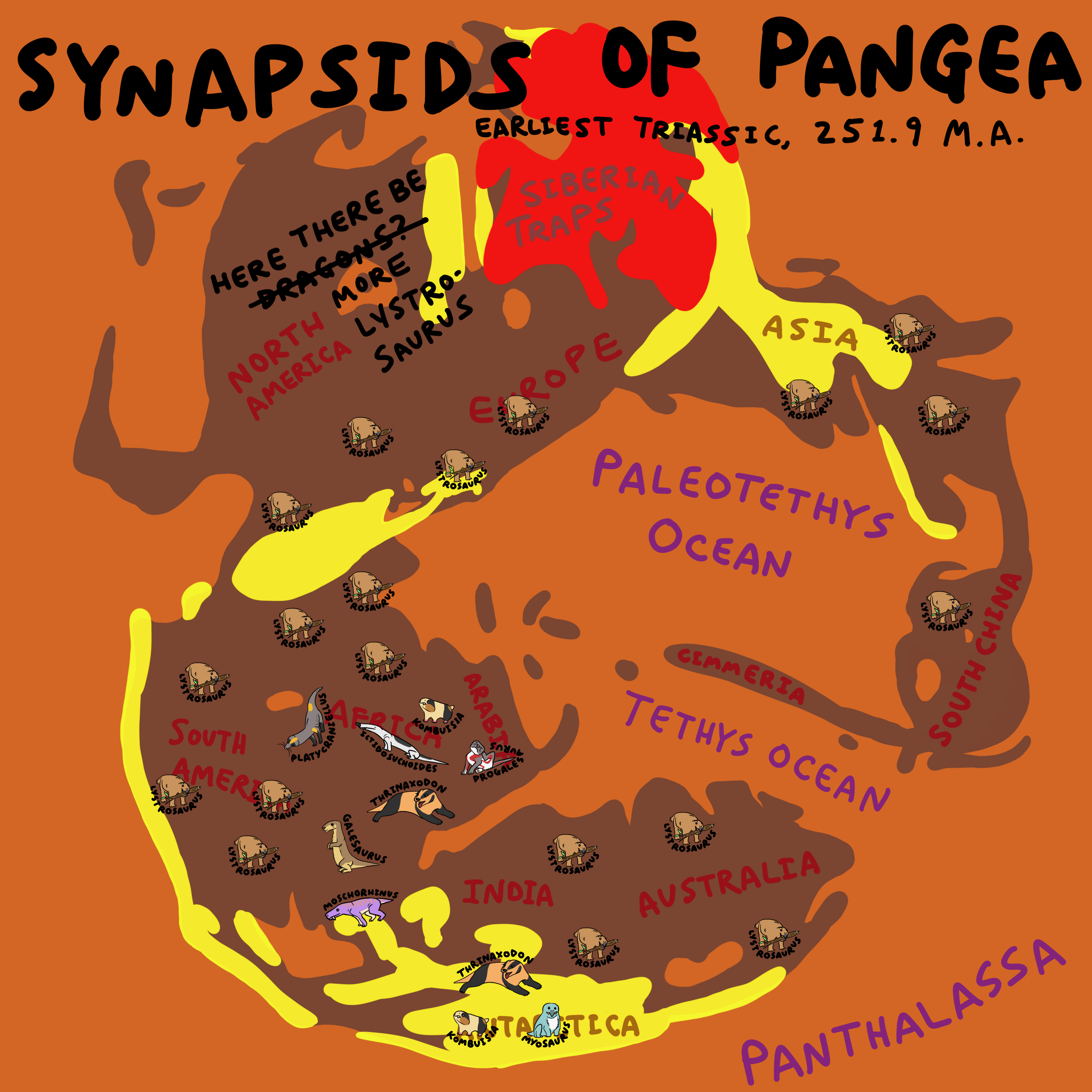

As a final installment in my comprehensive prehistoric world maps, I present the world of the end-Permian, right before the most terrible extinction the world has ever seen. The configuration of continents during the Permian period was much the same as in the Triassic, except that since the climate was a bit cooler and drier, more land area was exposed, and the big uncrossable desert in the middle of the C-shaped continent wasn’t quite as intense or uncrossable. This means that the faunal assemblages of the north and south were more similar than during the Triassic, with representatives from all major groups present in both places.

The further back in time we go, the less fossil material exists that’s survived that long. As such, my Triassic map had fewer animals on it than my Cretaceous one, and my Permian map has even fewer, with huge blank expanses from where no fossils are known. That doesn’t mean that animals didn’t live there at the time–it’s overwhelmingly likely that a similar fauna as was found in Siberia populated North America, and perhaps some strange isolated, monsoon-adapted extremophile animals lived in the Cimmerian archipelago.

As with my previous two maps, I only drew the most diverse and abundant group on Earth at that time–in this case, the mammal precursors known as synapsids. While it’s unfortunate that many weird and wonderful synapsids like the fin-backed pelycosaurs, long-necked dinocephalians, and tiny-headed caseasaurs had already gone extinct by the end of the Permian, there were many charismatic taxa still thriving right up until the apocalypse began.

Since tetrachromatic vision is the ancestral condition and mammal ancestors hadn’t undergone two hundred million years of subjugation by the dinosaurs yet, it’s likely that these animals were very colorful! Unlike certain dinosaurs, there isn’t any preserved evidence of color known from Permian synapsids, so I took liberties to color them however I wanted, taking inspiration from modern mammals, reptiles, and birds (which, though not related to synapsids, are probably representative of the level of colorfulness our Paleozoic ancestors might have been).

Also, none of these guys have external ears. It’s not known exactly when external ears arose, but it’s probably sometime during the Jurassic. Some of the more advanced end-Permian critters like the cynodonts may have been able to hear some airborne sounds, but with much less acuity than modern mammals, since their ear bones were still part of the jaw. This would have made them less able to freely vibrate, both because they were bulky and because they were attached to other skull components, and it would have made it so that breathing and chewing noises would significantly interfere with hearing. Cynodonts and more basal synapsids would have been able to hear sounds conducted through the ground, though, like the vibrations of each other’s footsteps or low rumbles they may have used to communicate, like elephants.

Let’s go through each major group, from least closely related to modern mammals to most mammaly.

Biarmosuchians

Burnetia, Paraburnetia, Lycaenodon, and Ictidorhinus

These guys are the most basal of the groups still alive at the end of the Permian. These mostly medium-sized carnivores were almost certainly fully cold-blooded, and therefore weren’t furry, though I have given some of them whiskers that would have been useful for sensing. It’s likely that hair first evolved for sensory purposes and later was repurposed for thermoregulation and display.

Three of these biarmosuchians were in or very closely related to a more derived subgroup called burnetiids, which had all kinds of weird bumps on their skulls. In Paraburnetia and Burnetia, those things on the sides of the head aren’t earflaps, but are bony protrusions that may have supported keratinous horns. Given the extreme showiness of their skulls, the bumps had to have been important display features, and burnetiids were therefore probably particularly showy, colorful animals.

Most biarmosuchians are monotypic, or known from a single fossil specimen, so not a lot is known about these flamboyant creatures. Did only the males have those bumpy protrusions? Were they covered by skin, horn, nothing, or something else? The bone shows signs of being very fast-growing, indicating that it probably was a sexual characteristic that developed during puberty, but the preservation is too poor on the specimens we have to allow scientists to guess what it might have looked like in life [1].

Ictidorhinus was not a burnetiid or close to one, so I didn’t give it head bumps. But since biarmosuchians are so basal, it’s the most reptilian of all the animals on the map.

Gorgonopsians

Leontosaurus, Cyonosaurus, Aelurosaurus, Arctops, Arctognathus, Sycosaurus, Inostrancevia, and Smilesaurus

Perhaps the most charismatic of all Permian fauna are the gorgonopsians, with their lion heads and saber teeth. While still basal and cold-blooded, they were the top predators of the Late Permian, the largest of which, Inostrancevia, may have weighed half a tonne, or the size of a very large tiger.

While it’s unknown whether their saber teeth would have been visible outside the mouth in life, it’s not impossible that they would have been, especially because ancestral amniotes didn’t have the flexible, loose facial skin that allow modern mammals to chew with their mouths closed and make complex facial expressions. Certain modern animals with large, non-tusk canines, like muntjac deer, red foxes, and Tasmanian devils, have their teeth protruding from their mouths most or all of the time, without ill effects on the enamel. So I chose to depict my gorgonopsians that way, mostly because it’s more fun.

While Inostrancevia might have been the biggest, the wolf-sized Smilesaurus had perhaps the proportionally largest canines, along with a chin flange to protect them from sideways knocks. Unlike later mammals, gorgonopsians constantly replaced their teeth throughout their lifetimes, more like modern reptiles, and would have been able to regrow their sabers if they were broken or lost. It’s likely that new sabers would’ve started growing in on the inside of the old ones, resulting in periods of double saber teeth, rather than periods of missing teeth, which would have made it difficult to hunt. This is also how later saber-toothed cats and cat relatives handled it, though they only replaced their teeth once in their lives. It takes a long time to grow a saber–possibly as long as 30 months in Smilodon fatalis [2]!

A funny note–Cyonosaurus means “dog reptile” while Aelurosaurus means “cat reptile”. I tried to color them accordingly.

Dicynodonts

Lystrosaurus, Compsodon, Dicynodon, Odontocyclops, Dinanomodon, Kwazulusaurus, Rhachiocephalus, Vivaxosaurus, Gordonia, Daqingshanodon, Jimusaria, Turfanodon, Diictodon, Myosaurus, Katumbia, Kombuisia, Pristerodon, Oudenodon, Dicynodontoides, Daptocephalus, and Aulacephalodon

Another famous group of early synapsids was the rolypoly dicynodonts, a group of beaked, tusked herbivores that ranged from guinea pig-sized to hippo-sized. There’s evidence in the form of bone histology and preserved fur in gorgonopsian poos that point to dicynodonts as having been warm-blooded, so I drew all mine as being fuzzy. But since other synapsids more closely related to modern mammals are thought to have still been cold-blooded, it seems that dicynodonts evolved endothermy independently.

Some of the smaller dicynodonts like Diictodon and Lystrosaurus are known to have been social burrowers, as entire families have been found entombed in their burrows.

Small dicynodonts like the Antarctic Myosaurus and Kombuisia, as well as the prolific Lystrosaurus, are known to have survived the Great Dying at the end of the Permian and later radiated back into even bigger forms like the seven-tonne (elephant-sized) Lisowicia. Here’s what the world looked like a mere 100,000 years after the snapshot at the top of this post:

Therocephalians

Muchia, Karenites, Scaloposaurus, Scalopognathus, Scalopodontes, Scaloporhinus, Annatherapsidus, Malasaurus, Chlynovia, Perplexisaurus, Ictidosuchus, Ictidosuchops, Ictidosuchoides, Homodontosaurus, Lycideops, Choerosaurus, Promoschorhynchus, Tetracynodon, and Moschorhinus

The largest, catch-all grouping on this map, this is likely a wastebasket taxon that needs some sorting out. Sometimes Therocephalia is recovered as the sister group to Cynodontia (which includes modern mammals), but sometimes Cynodontia is nested inside Therocephalia, making it a paraphyletic clade, or an evolutionary “grade” on the road to true mammals. Either way, I’m running with the hypothesis that only dicynodonts and true cynodonts developed endothermy, so my therocephalians are not furry. There’s some evidence in the form of bone histology (growth patterns in thin slices of bone) that suggest therocephalians like Moschorhinus were able to grow faster or slower depending on resource availability, which is a characteristic of ectotherms [3].

These Late Permian therocephalians were quite diverse in size and shape. The possibly semiaquatic Perplexisaurus was only about a foot long (30cm), as was the mole-like Homodontosaurus with its upturned snout, while the super-elongated Ictidosuchoides and the chunky, gorgonopsian-like Moschorhinus were closer to 5 feet long (1.5m) and may have weighed close to 100kg, or the size of a jaguar.

Interestingly, it’s the larger therocephalians that seemed to survive the end-Permian extinction better, though the sample size is very small, so it could just be chance. Usually, the smaller, more generalist members of a lineage are the most likely to survive, but maybe in the case of therocephalians it was the larger members that were the generalists.

Cynodonts

Galesaurus, Progalesaurus, Platycraniellus, Thrinaxodon, Dvinia, and Procynosuchus

Last but certainly not least, we have the cynodonts, the group that includes true mammals. I am a cynodont!

In the Permian, cynodonts were certainly not the most important movers and shakers in their environments. They were mostly small, weasel to dog-sized carnivores and insectivores living in the shadows of the much larger gorgonopsians and dicynodonts. Who could have predicted that this group of underdogs would go on to inherit the planet, some 200 million years later?

Cynodonts and dicynodonts seem to have been particularly good at weathering the Great Dying, perhaps due to their fossorial habits, their warm blood granting them the ability to move around actively to forage even during a nuclear winter, and their ability to save energy in a state of torpor when food was particularly scarce. Or it could’ve been pure luck, or all of the above.

Many of the survivors of the Great Dying seem to have migrated to Antarctica as a way to escape the heat: after all, Siberia was exploding, and Antarctica was the furthest possible land area from there. After things quieted down a little and the lava began to cool, they radiated back across the still-walkable continents. Thank goodness it was Siberia that was on fire, rather than, say, Africa, which was much more central. The Great Dying was the closest that life has come to being reduced to only invertebrate, or even only microbial survivors. Since large-bodied tetrapods could only survive on the very furthest point from where the lava was flowing, if Pangea had been just a little smaller or the eruptions just a little less northerly, we probably wouldn’t be here today!

References

[1] Kulik, Z. T., & Sidor, C. A. (2019). The original boneheads: histologic analysis of the pachyostotic skull roof in Permian burnetiamorphs (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia). Journal of Anatomy, 235(1), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12987

[2] Tseng, Z. J. (2024). Bending performance changes during prolonged canine eruption in saber‐toothed carnivores: A case study of Smilodon fatalis. The Anatomical Record. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25447

[3] Huttenlocker, A. K., & Botha-Brink, J. (2013). Body size and growth patterns in the therocephalian Moschorhinus kitchingi (Therapsida: Eutheriodontia) before and after the end-Permian extinction in South Africa. Paleobiology, 39(2), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1666/12020